Chapter 66 Shoulder dystocia

Introduction

Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric emergency with a potentially catastrophic outcome. It refers to deliveries where manoeuvres other than gentle downward traction are needed to complete the delivery of the anterior shoulder (Resnik 1980).

Mechanism

In a normal labour the shoulders enter the pelvic brim in the oblique or transverse diameter. (For a complete description of the normal mechanism of labour, see Ch. 37.) In shoulder dystocia there is an arrest of the normal mechanism of labour as the shoulders attempt to enter the pelvis in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic brim. The diameter of the fetal shoulders or bisacromial diameter is 12.4 cm and should fit comfortably through the widest diameter of the pelvic brim. Shoulders are sufficiently flexible to allow those of even a large baby to negotiate the pelvis.

There is no current agreement on a definition for shoulder dystocia. Smeltzer (1986) suggests that shoulder dystocia is a failure of the shoulders to spontaneously traverse the pelvis after the fetal head has been delivered.

Some or all of the following will alert midwives to suspect that shoulder dystocia has occurred:

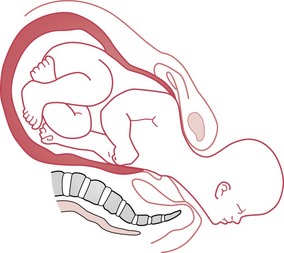

The turtle sign is caused by reverse traction from the shoulders. The anterior shoulder is wedged onto the symphysis pubis and the posterior shoulder may still be above the pelvic brim (Fig. 66.1). Pulling to deliver the anterior shoulder is likely to impede delivery by wedging the infant’s anterior shoulder more firmly onto the symphysis pubis and can cause damage to the brachial plexus (see Fig. 66.10).

Incidence and risk

The incidence of shoulder dystocia is around 0.6% at term, but the risk increases to 1.3% by 42 weeks’ gestation (Johnstone & Meyerscough 1998, RCOG 2005). However, a lack of agreement over the definition affects the number of cases reported (Johnstone & Myerscough 1998).

The risk of shoulder dystocia rises with increasing birthweight and length of gestation, birth order and maternal age (Acker et al 1986, Gross et al 1987, Johnstone & Myerscough 1998). Johnstone & Myerscough (1998) point out that half of all babies with shoulder dystocia weigh less than 4 kg and are not considered to be large, and only 4% of large babies suffer shoulder dystocia.

Mortimore & McNabb (1998) suggested that some practitioners may use the term shoulder dystocia to describe any general difficulty with the delivery of the shoulders. If RCOG (2005) diagnostic criteria for shoulder dystocia cannot be fulfilled, then ‘difficulty with delivery of the shoulders’ should be recorded to avoid overdiagnosis (Mahran et al 2008).

Identification of risk factors

Maternal obesity is a frequently occurring factor associated with shoulder dystocia (maternal BMI >30 at booking, or weight at delivery >90 kg) (RCOG 2005). The greater the maternal weight, the higher the risk (Athukorala et al 2007).

Maternal diabetes and gestational diabetes are associated with asymmetrical fetal growth. The body and particularly the shoulders are larger than in babies of mothers who are not diabetic (Acker et al 1985).

Spellacy et al (1985) studied the data from 33,545 deliveries and concluded that women with either insulin-dependent or gestational diabetes are more likely to deliver a macrosomic infant and are therefore at a higher risk of a delivery complicated by shoulder dystocia.

Fetal macrosomia is the strongest independent risk factor for shoulder dystocia (Athukorala et al 2007). Infants of non-diabetic mothers who have birthweights of 4000–4449 g have a 10% risk of shoulder dystocia, while infants of the same weight born to diabetic mothers have a 31% risk of developing shoulder dystocia, because of their asymmetrical growth (Acker et al 1985, Spellacy et al 1985).

A previous delivery complicated by shoulder dystocia is a predictive risk factor, with a recurrence rate of around 10% for subsequent deliveries (Olugbile & Mascarenhas 2000, Smith et al 1994).

Use of ultrasound to predict the macrosomic fetus

Ultrasonic estimation of fetal weight is widely used, as it is objective and can be reproduced (Combs et al 1993). However, Chauhan et al (1992) suggest that ultrasonic diagnosis of the large infant is generally no more accurate than clinical estimation and that if a woman has had a baby before, her own estimate is likely to be as good as an ultrasound measurement. Elective induction for infants diagnosed as macrosomic on ultrasound scan increases the risk of caesarean section and does not prevent shoulder dystocia (Hall 1996, RCOG 2005).

Prediction of impending shoulder dystocia

Most labours preceding shoulder dystocia are normal (McFarland et al 1995). In some cases the first hint of trouble the midwife may experience during a delivery is the slow extension of the baby’s head and then the chin remaining tight against the mother’s perineum (Coates 1995). In spite of current technology, shoulder dystocia usually occurs unexpectedly (RCOG 2005).

Unfortunately, the absence of risk factors cannot be relied upon to exclude the possibility of shoulder dystocia. It is therefore important that the midwife has a sound knowledge of the interaction between the physiology and mechanism of labour and the manoeuvres that may be used to complete the delivery in the shortest time possible. This is to ensure the best outcome for the mother and her infant. All members of the labour ward team should be familiar with the agreed protocol, and ‘drills’ should be practised on a regular basis by all grades of staff (Draycott et al 2008, MCHRC 1998).

Manoeuvres for management of shoulder dystocia

McRoberts’ manoeuvre

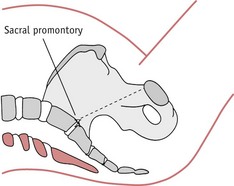

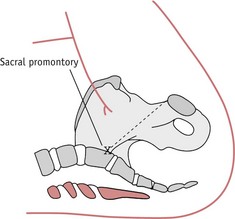

This is the first choice of manoeuvre in most circumstances as it has been proven to be safe and effective. The manoeuvre (Fig. 66.2) requires the mother to lie flat on her back (or with a slight lateral tilt to prevent supine hypotension), then she is assisted into an exaggerated knee–chest position (Gonik et al 1983).

Once the mother has adopted this position, the midwife should be able to proceed with a normal delivery of the shoulders. Smeltzer (1986) suggests that this manoeuvre:

This was supported by later radiological studies (Gherman et al 2000).

Maternal and fetal models were used by Gonik et al (1989) to assess the forces used to extract the fetal shoulders. The McRoberts’ manoeuvre was compared with the lithotomy position and consistently required less force to remove the shoulders.

RCOG (2005) advocates the use of the McRoberts’ manoeuvre as a first step if shoulder dystocia is diagnosed, and, if the manoeuvre is unsuccessful at the first attempt, to try it a second time before attempting other manoeuvres.

All-fours position

When there is a minor degree of shoulder dystocia, movement of the mother can dislodge the obstruction so the shoulders can negotiate the pelvis normally; assisting the mother into an all-fours position can work in this way. The all-fours position (Fig. 66.5) also can be used to optimize the space in the sacral curve for the midwife to undertake the direct or rotational manoeuvres as described below. Generally, this position, which acts as an ‘upside-down McRoberts’ position’ carries the same positive effects as above, and will allow the posterior shoulder to deliver first (Macdonald & Day-Stirk 1995).

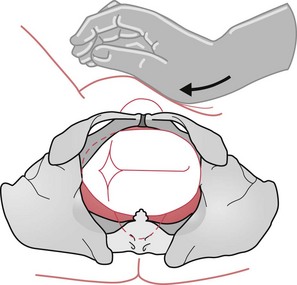

Suprapubic pressure

The application of suprapubic pressure is intended to adduct and then displace the anterior shoulder away from the symphysis pubis and so allow it to enter the pelvis in an oblique diameter (Fig. 66.6). Pressure is applied by either the midwife or assistant, using the flat of the hand against the baby’s back in the direction that the baby is facing.

Figure 66.6 Diagram to illustrate the use and direction of suprapubic pressure when the back is on the woman’s left.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree