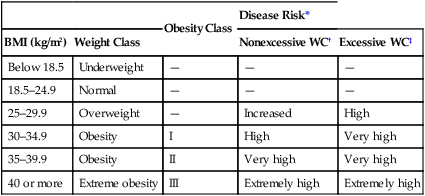

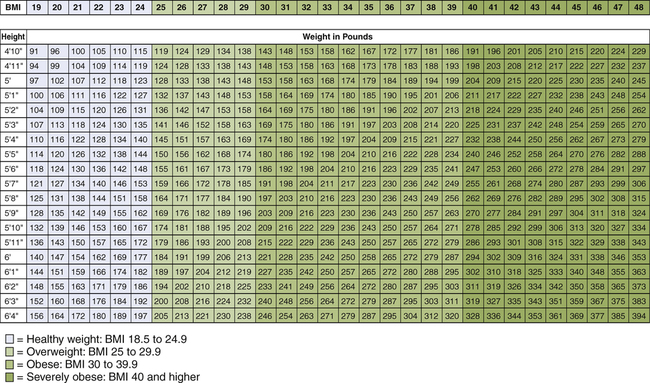

CHAPTER 82 The body mass index (BMI), which is derived from the patient’s weight and height, is a simple way to estimate body fat content. Studies indicate a close correlation between BMI and total body fat. The BMI is calculated by dividing a patient’s weight (in kilograms) by the square of the patient’s height (in meters). Hence, BMI is expressed in units of kg/m2. BMI can also be calculated using the patient’s weight in pounds and height in inches (Fig. 82–1). According to the federal guidelines, a BMI of 30 or higher indicates obesity. Individuals with a BMI of 25 to 29.9 are considered overweight, but not obese. There is good evidence that the risk of cardiovascular disease and other disorders rises significantly when the BMI exceeds 25. When the BMI exceeds 30, there is an increased risk of death. These specific associations between BMI and health risk do not apply to elderly adults, growing children, or women who are pregnant or lactating. Nor do they apply to competitive athletes or bodybuilders, who are heavy because of muscle mass rather than excess fat. Table 82–1 summarizes weight classifications based on BMI. TABLE 82–1 Disease Risk Based on BMI and WC *Risk for hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, relative to individuals of normal weight. †Nonexcessive WC = waist circumference of 40 inches or less for men, and 35 inches or less for women. ‡Excessive WC = waist circumference above 40 inches for men, and above 35 inches for women. Adapted from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: Evidence Report. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1998. Waist circumference (WC) is an indicator of abdominal fat content, an independent risk factor for obesity-related diseases. Accumulation of fat in the upper body, and especially within the abdominal cavity, poses a greater risk to health than does accumulation of fat in the lower body (hips and thighs). People with too much abdominal fat are at increased risk of insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertension, coronary atherosclerosis, ischemic stroke, and dementia. Fat distribution can be estimated simply by looking in the mirror: an apple shape indicates too much abdominal fat, whereas a pear shape indicates fat on the hips and thighs. Measurement of WC provides a quantitative estimate of abdominal fat. A WC exceeding 40 inches (102 cm) in men or 35 inches (88 cm) in women signifies an increased health risk—but only for people with a BMI between 25 and 34.9 (see Table 82–1). Not surprisingly, health risk rises as BMI gets larger (see Table 82–1). In addition, the risk is increased by the presence of an excessive WC. The risk is further increased by weight-related diseases and cardiovascular risk factors. In the absence of an excessive WC and other risk factors, health risk is minimal with a BMI below 25, and relatively low with a BMI below 30. Conversely, a BMI of 30 or more indicates significant risk. In the presence of an excessive WC, health risk is high for all individuals with a BMI above 25. Table 82–2 lists Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs for obesity, and summarizes their approved indications, mechanism of action, major side effects, and status under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). TABLE 82–2 Drugs Approved for Weight Loss in the United States

Drugs for weight loss

Assessment of weight-related health risk

Body mass index.

Obesity Class

Disease Risk*

BMI (kg/m2)

Weight Class

Nonexcessive WC†

Excessive WC‡

Below 18.5

Underweight

—

—

—

18.5–24.9

Normal

—

—

—

25–29.9

Overweight

—

Increased

High

30–34.9

Obesity

I

High

Very high

35–39.9

Obesity

II

Very high

Very high

40 or more

Extreme obesity

III

Extremely high

Extremely high

Adult weight classification based on body mass index (BMI).

Adult weight classification based on body mass index (BMI).

Adapted from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: Evidence Report. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1998.

Waist circumference.

Risk status.

Overview of obesity treatment

Treatment modalities

Drug therapy.

Drug

FDA-Approved Indications

Mechanism

Weight Loss Beyond That with Placebo

Adverse Effects

Schedule IV Controlled Substance

Orlistat

[Alli, Xenical]

Weight loss: long term

Reduces fat absorption: inhibits lipase

3%

Oily spotting, flatulence, diarrhea, fecal urgency

No

Phentermine

[Adipex-P, Ionamin]

Weight loss: short term

Suppresses appetite: sympathomimetic amine

4%

Nervousness, insomnia, palpitations, tachycardia, mild increase in blood pressure

Yes

Diethylpropion

(generic only)

Weight loss: short term

Suppresses appetite: sympathomimetic amine

3%

Same as phentermine

Yes ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Drugs for weight loss

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access