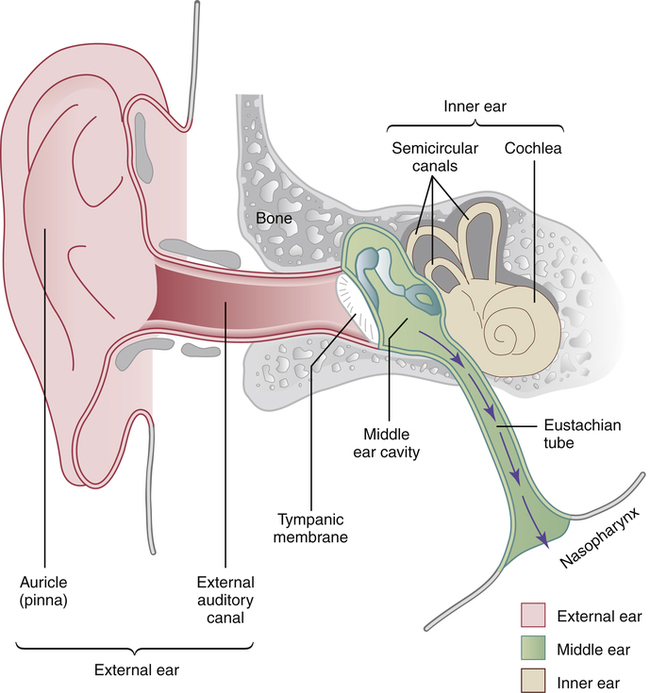

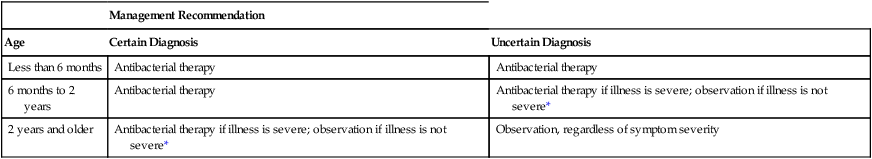

CHAPTER 106 The ear has three major divisions: the external ear, middle ear, and inner ear (Fig. 106–1). Their primary features are as follows: • The external ear consists of (1) the auricle or pinna (the cartilaginous flap visible on the side of the head that serves to collect sound waves); and (2) the external auditory canal (EAC), a skin-lined tube that directs sound waves from the auricle to the tympanic membrane (eardrum). The surface of the EAC is coated with cerumen (earwax), a hydrophobic substance that blocks penetration of water and helps protect against bacterial and fungal infection. • The middle ear is the chamber that houses the malleus, incus, and stapes—three tiny bones that transmit sound vibrations from the eardrum to the inner ear. The middle ear is bounded laterally by the tympanic membrane, which walls off the middle ear from the external ear. The eustachian tube (auditory tube) connects the middle ear with the nasopharynx, and thereby allows air pressure within the middle ear to equalize with air pressure in the environment. The mucociliary epithelium that lines the eustachian tube sweeps bacteria out of the middle ear into the nasopharynx. • The inner ear consists of the semicircular canals and the cochlea. The canals provide our sense of balance. The cochlea houses the apparatus of hearing. How does AOM develop? As a rule, the process begins with a viral infection of the nasopharynx, which can cause blockage of the eustachian tube, which in turn can cause negative pressure in the middle ear. When the eustachian tube opens, causing pressure equalization, bacteria and viruses can be sucked in. If the mucociliary system is sufficiently impaired, it will be unable to transport these pathogens back to the nasopharynx. Otitis media results when bacteria colonize the fluid of the middle ear and/or when viruses colonize cells of the middle-ear mucosa. As indicated in Table 106–1, bacteria are present in 70% to 90% of fluid samples taken from the middle ear of children with AOM, and viruses are present in nearly 50%. The most common bacterial pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae (40% to 50%), Haemophilus influenzae (20% to 25%), and Moraxella catarrhalis (10% to 15%). TABLE 106–1 Primary Pathogens Found in Fluid from the Middle Ear of Children with Acute Otitis Media • Most episodes of AOM resolve spontaneously. • Immediate antibacterial therapy is only marginally superior to observation at causing AOM resolution, and is no better at relieving pain or distress. • Parents find the observation approach acceptable. • Delaying antibacterial therapy does not significantly increase the risk of mastoiditis, which can occur when bacteria invade the mastoid bone. Criteria for choosing between observation and initial antibacterial therapy are summarized in Table 106–2. The choice is based on patient age, how certain the diagnosis is, and severity of symptoms. As indicated, all children less than 6 months old should receive antibiotics, regardless of diagnostic certainty or symptom severity. Among children 6 months to 2 years old, antibiotics are indicated whenever the diagnosis is certain. If the diagnosis is uncertain, antibiotics are indicated only if symptoms are severe. For children age 2 years and older, antibacterial therapy is indicated only if the diagnosis is certain, and then only if symptoms are severe. In all other cases, observation is the preferred strategy. TABLE 106–2 Criteria for Choosing Initial Antibacterial Therapy Versus Observation in Children with AOM *Severe illness = moderate to severe otalgia or fever of 39°C or higher, nonsevere illness = mild otalgia and fever below 39°C in the past 24 hours.

Drugs for the ear

Anatomy of the ear

Anatomy of the ear.

Anatomy of the ear.

The purple arrows indicate flow of the mucociliary system, which can transport bacteria out of the middle ear.

Otitis media and its management

Acute otitis media

Characteristics, pathogenesis, and microbiology

Pathogen

Children with the Pathogen (%)

Streptococcus pneumoniae

40–50

Haemophilus influenzae

20–25

Moraxella catarrhalis

10–15

No bacteria found

20–30

Respiratory viruses (with or without bacteria)

48

Standard treatment

Management Recommendation

Age

Certain Diagnosis

Uncertain Diagnosis

Less than 6 months

Antibacterial therapy

Antibacterial therapy

6 months to 2 years

Antibacterial therapy

Antibacterial therapy if illness is severe; observation if illness is not severe*

2 years and older

Antibacterial therapy if illness is severe; observation if illness is not severe*

Observation, regardless of symptom severity

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Drugs for the ear

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access