Discuss the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of anxiety.

Discuss the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of sleep and insomnia.

Discuss the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of sleep and insomnia.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the benzodiazepines.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the benzodiazepines.

Discuss the various nonbenzodiazepines used to reduce anxiety and produce hypnosis in terms of their action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Discuss the various nonbenzodiazepines used to reduce anxiety and produce hypnosis in terms of their action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Implement the nursing process in the care of the patient being treated with benzodiazepines.

Implement the nursing process in the care of the patient being treated with benzodiazepines.

Clinical Application Case Study

Lorraine Terrence, an 83-year-old widow who lives alone, is in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. She has a history of cardiovascular disease and hypertension and has been admitted to the local hospital for observation after complaints of chest pain. At present, she is very anxious and agitated. The admitting nurse received a telephone call from Mrs. Terrence’s daughter, who lives out of town. The daughter states that her mother has experienced anxiety and depression for many years and her symptoms have worsened since her father died 6 months ago. The daughter does not know what medications her mother currently takes, and she is concerned that her mother lives alone and wants her to move to a nursing home. The physician orders the following medications: alprazolam (Xanax) for anxiety, citalopram (Celexa) for depression, and zolpidem (Ambien) for sleep.

KEY TERMS

Anterograde amnesia: short-term memory loss

Anxiety: common disorder that may be referred to as nervousness, tension, worry, or other terms that denote an unpleasant feeling

Anxiety disorder: severe anxiety that is prolonged and impairs the ability to function in usual activities of daily living

Anxiolytics: antianxiety drugs

Hypnotics: drugs that produce sleep

Insomnia: prolongs difficulty in going to sleep or staying asleep long enough to feel rested

Sedatives: drugs that produce central nervous system depression

Introduction

This chapter introduces the pharmacological care of the patient who is experiencing anxiety and/or insomnia. Antianxiety and sedative-hypnotic drugs are central nervous system (CNS) depressants that have similar effects. Anxiolytics are antianxiety drugs, sedatives promote relaxation, and hypnotics produce sleep. The difference between the effects depends largely on dosage. Large doses of antianxiety and sedative drugs produce sleep, and small doses of hypnotics have anxiolytic or sedative effects. Also, therapeutic doses of hypnotics taken at bedtime may have residual sedative effects (“morning hangover”) the following day. Because these drugs produce varying degrees of CNS depression, some are also used as anticonvulsants and anesthetics.

Overview of Anxiety

To promote understanding of the uses and effects of both benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines, anxiety and insomnia are described in the following sections. The clinical manifestations of these disorders are similar and overlapping; that is, daytime anxiety may be manifested as nighttime difficulty in sleeping because the person cannot “turn off” worries, and difficulty in sleeping may be manifested as anxiety, fatigue, and decreased ability to function during usual waking hours.

Etiology

Anxiety is a common disorder that may be referred to as nervousness, tension, worry, or other terms that denote an unpleasant feeling. It occurs when a person perceives a situation as threatening to physical, emotional, social, or economic well-being. Anxiety may occur in association with everyday events related to home, work, school, social activities, and chronic illness, or it may occur episodically, in association with acute illness, death, divorce, losing a job, starting a new job, or taking a test. Situational anxiety is a normal response to a stressful situation. It may be beneficial when it motivates the person toward constructive, problem-solving, coping activities. Symptoms may be quite severe, but they usually last only 2 to 3 weeks.

Although there is no clear boundary between normal and abnormal anxiety, when anxiety is severe or prolonged and impairs the ability to function in usual activities of daily living, it is called an anxiety disorder. The American Psychiatric Association delineates anxiety disorders as medical diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). This classification includes several types of anxiety disorders, as described in Box 53.1. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is emphasized in this chapter.

BOX 53.1 Anxiety Disorders

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Major diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) include worry about two or more circumstances and multiple symptoms for 6 months or longer and elimination of disease processes or drugs as possible causes. The frequency, duration, or intensity of the worry is exaggerated or out of proportion to the actual situation. Symptoms are related to motor tension (e.g., muscle tension, restlessness, trembling, fatigue), overactivity of the autonomic nervous system (e.g., dyspnea, palpitations, tachycardia, sweating, dry mouth, dizziness, nausea, diarrhea), and increased vigilance (feeling fearful, nervous, or keyed up; difficulty concentrating; irritability; insomnia).

Symptoms of anxiety occur with numerous disease processes, including medical disorders (e.g., hyperthyroidism, cardiovascular disease, cancer) and psychiatric disorders (e.g., mood disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders). They also frequently occur with drugs that affect the central nervous system (CNS). With CNS stimulants (e.g., nasal decongestants, antiasthma drugs, nicotine, caffeine), symptoms occur with drug administration; with CNS depressants (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines), symptoms are more likely to occur when the drug is stopped, especially if stopped abruptly.

When the symptoms are secondary to medical illness, they may decrease as the illness improves. However, most people with GAD experience little relief when one stressful situation or problem is resolved. Instead, they quickly move on to another worry. Additional characteristics of GAD include its chronicity, although the severity of symptoms fluctuates over time; its frequent association with somatic symptoms (e.g., headache, gastrointestinal complaints, including irritable bowel syndrome); and its frequent coexistence with depression, other anxiety disorders, and substance abuse or dependence.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

An obsession involves an uncontrollable desire to dwell on a thought or a feeling; a compulsion involves repeated performance of some act to relieve the fear and anxiety associated with an obsession. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by obsessions or compulsions that are severe enough to be time consuming (e.g., take more than an hour per day), cause marked distress, or impair the person’s ability to function in usual activities or relationships. The compulsive behavior provides some relief from anxiety but is not pleasurable. The person recognizes that the obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable and attempts to resist them. When patients resist or are prevented from performing the compulsive behavior, they experience increasing anxiety and often abuse alcohol or antianxiety, sedative-type drugs in the attempt to relieve anxiety.

Panic Disorder

Panic disorder involves acute, sudden, recurrent attacks of anxiety, with feelings of intense fear, terror, or impending doom. It may be accompanied by such symptoms as palpitations, sweating, trembling, shortness of breath or a feeling of smothering, chest pain, nausea, or dizziness. Symptoms usually build to a peak over about 10 minutes and may require medication to be relieved. Afterward, the person is usually preoccupied and worried about future attacks.

A significant number (50%-65%) of patients with panic disorder are thought to also have major depression. In addition, some patients with panic disorder also develop agoraphobia, a fear of having a panic attack in a place or situation where one cannot escape or get help. Combined panic disorder and agoraphobia often involves a chronic, relapsing pattern of significant functional impairment and may require lifetime treatment.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD develops after seeing or being involved in highly stressful events that involve actual or threatened death or serious injury (e.g., natural disasters, military combat, violent acts such as rape or murder, explosions or bombings, serious automobile accidents). The person responds to such an event with thoughts and feelings of intense fear, helplessness, or horror and develops symptoms such as hyperarousal, irritability, outbursts of anger, difficulty sleeping, difficulty concentrating, and an exaggerated startle response. These thoughts, feelings, and symptoms persist as the traumatic event is relived through recurring thoughts, images, nightmares, or flashbacks in which the actual event seems to be occurring. The intense psychic discomfort leads people to avoid situations that remind them of the event; become detached from other people; have less interest in activities they formerly enjoyed; and develop other disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, major depression, alcohol or other substance abuse).

The response to stress is highly individualized and the same event or type of event might precipitate PTSD in one person and have little effect in another. Thus, most people experience major stresses and traumatic events during their lifetimes, but many do not develop PTSD. This point needs emphasis because many people seem to assume that PTSD is the normal response to a tragic event and that intensive counseling is needed. For example, counselors converge on schools in response to events that are perceived to be tragic or stressful. Some authorities take the opposing view, however, that talking about and reliving a traumatic event may increase anxiety in some people and thereby increase the likelihood that PTSD will occur.

Social Anxiety Disorder

This disorder involves excessive concern about scrutiny by others, which may start in childhood and be lifelong. Affected people are afraid they will say or do something that will embarrass or humiliate them. As a result, they try to avoid certain situations (e.g., public speaking) or experience considerable distress if they cannot avoid them. They are often uncomfortable around other people or experience anxiety in many social situations. SAD may be inherited; there is a threefold increase in the occurrence of SAD in related family members.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of anxiety disorders is unknown, but there is evidence of a biologic basis and possible imbalances among several neurotransmission systems. A simplistic view involves an excess of excitatory neurotransmitters (e.g., norepinephrine) or a deficiency of inhibitory neurotransmitters (e.g., gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA]).

The noradrenergic system is associated with the hyperarousal state experienced by patients with anxiety (i.e., feelings of panic, restlessness, tremulousness, palpitations, hyperventilation), which is attributed to excessive norepinephrine. Norepinephrine is released from the locus coeruleus (LC) in response to an actual or a perceived threat. The LC is a brainstem nucleus that contains many noradrenergic neurons and has extensive projections to the limbic system, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum. Certain observations lend support to the role of the noradrenergic system in anxiety. Drugs that stimulate activity in the LC (e.g., caffeine) may cause symptoms of anxiety, and drugs used to treat anxiety (e.g., benzodiazepines) decrease neuronal firing and norepinephrine release in the LC.

Neuroendocrine factors also play a role in anxiety disorders. Perceived threat or stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), one of its components. CRF activates the LC, which then releases norepinephrine and generates anxiety. Overall, authorities consider CRF important in integrating the endocrine, autonomic, and behavioral responses to stress.

GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and spinal cord. Gamma-aminobutyric acidA (GABAa) receptors are attached to chloride channels in nerve cell membranes. When GABA interacts with GABAa receptors, chloride channels open, chloride ions move into the neuron, and the nerve cell is less able to be excited (i.e., generate an electrical impulse).

The serotonin system, although not as well understood, also may play a role in anxiety. Both serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin receptor agonists are now used to treat anxiety disorders. Research has suggested two possible roles for the serotonin receptor HT1A. During embryonic development, stimulation of HT1A receptors by serotonin may contribute to the development of normal brain circuitry necessary for normal anxiety responses. However, during adulthood, some serotonin reuptake inhibitors act through HT1A receptors to reduce anxiety responses.

Additional causes of anxiety disorders include medical conditions (anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition according to the DSM-IV-TR), psychiatric disorders, and substance abuse. Almost all major psychiatric illnesses may be associated with symptoms of anxiety (e.g., dementia, major depression, mania, schizophrenia). Anxiety related to substance abuse is categorized in the DSM-IV-TR as substance-induced anxiety disorder.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of anxiety include motor tension, such as muscle tension, restlessness, trembling, and fatigue; they also include overactivity of the autonomic nervous system, such as dyspnea, palpitations, tachycardia, sweating, dry mouth, dizziness, nausea, and diarrhea. Other clinical manifestations include increased vigilance, such as feeling fearful, nervous, or keyed up; difficulty concentrating; irritability; and insomnia. Box 53.1 summarizes the clinical manifestations of specific anxiety disorders defined by the DSM-IV-TR.

Drug Therapy

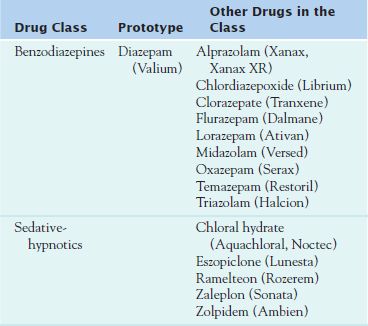

Benzodiazepines are widely used to treat anxiety disorders (Table 53.1). Benzodiazepines are useful in the short-term treatment symptoms of acute anxiety in response to stressful situations. Antidepressants (i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and newer miscellaneous drugs) are preferred as first-line drugs for long-term treatment of most chronic anxiety disorders, with benzodiazepines considered second-line drugs. Chapter 54 discusses antidepressant medications in more detail.

The barbiturates, a historically important group of CNS depressants, are obsolete for most uses, including treatment of anxiety and insomnia. A few may find use as intravenous (IV) general anesthetics (see Chap. 50), as treatment for seizure disorders (phenobarbital; see Chap. 52), and as drugs or abuse (see Chap. 57).

Overview of Sleep and Insomnia

Sleep is a recurrent period of decreased mental and physical activity during which a person is relatively unresponsive to sensory and environmental stimuli. Normal sleep allows rest, renewal of energy for performing activities of daily living, and alertness on awakening.

Etiology

Insomnia, prolonged difficulty in going to sleep or staying asleep long enough to feel rested, is the most common sleep disorder. Occasional sleeplessness is a normal response to many stimuli and is not usually harmful. Insomnia is said to be chronic when it lasts longer than 1 month. As in anxiety, several neurotransmission systems are apparently involved in regulating sleep-wake cycles and producing insomnia.

Insomnia has many causes. Medical disorders, such as chronic pain syndromes and fibromyalgia, and neurologic disorders, such as movement disorders or headaches, may lead to sleep disturbances. Psychiatric conditions and substance abuse may also play a role. Other causes of insomnia include environmental factors (e.g., light, temperature, noise, uncomfortable mattress) or stress-related factors (e.g., stressful life events, deadlines, new job, personal losses). Certain medications, including stimulants such as caffeine, some antidepressants, beta-blockers, and over-the-counter (OTC) and herbal medications, can cause sleep difficulties. Evidence supports the genetic susceptibility to factors such as light and stress on sleep hygiene.

Also, research has demonstrated that patients with insomnia show evidence of increased brain arousal, higher day and night body temperatures, and increased levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone. In addition, patients with insomnia have higher rates of depression and anxiety.

Pathophysiology

When a person retires for sleep, there is an initial period of drowsiness or sleep latency, which lasts about 30 minutes. After the person is asleep, cycles occur approximately every 90 minutes during the sleep period. During each cycle, the sleeper progresses from drowsiness (stage I) to deep sleep (stages III and IV). These stages are characterized by depressed body functions, non-rapid eye movement (non-REM), and nondreaming, and they are thought to be physically restorative. Activities that occur during these stages include increased tissue repair, synthesis of skeletal muscle protein, and secretion of growth hormone. At the same time, there is decreased body temperature, metabolic rate, glucose consumption, and production of catabolic hormones. A period of 5 to 20 minutes of REM, dreaming, and increased physiologic activity follow stage IV.

Experts believe that REM sleep is mentally and emotionally restorative; REM deprivation can lead to serious psychological problems, including psychosis. It is estimated that people spend about 75% of sleeping hours in non-REM sleep and about 25% in REM sleep. However, older adults often have a different pattern, with less deep sleep, more light sleep, more frequent awakenings, and generally more disruptions.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of insomnia include fatigue, lack of energy, and irritability. Patients with insomnia report diminished work performance and decreased concentration. Generally, patients with insomnia do not complain of daytime sleepiness. They tend to be overconcerned about their inability to fall asleep; the more they try to sleep, the more agitated they become, and the less they are able to fall asleep.

Drug Therapy

The main drugs used to treat insomnia are the benzodiazepines and the nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (see Table 53.1). However, it is important to note that drug companies market only a few benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia, although all are effective sedative-hypnotics. People also use OTC medications as sleep aids; these medications include antihistamines alone or in combination with pain relievers. Along with OTC medications, many herbal supplements are consumed to decrease stress, anxiety, and induce sleep. Box 53.2 summarizes herbal supplements that are commonly taken and may interact with other prescription medications administered for anxiety and sleep induction.

BOX 53.2 Herbal Supplements Commonly Used to Reduce Anxiety and Produce Hypnosis

Kava

This supplement is derived from a shrub found in many South Pacific islands. It is claimed to be useful in numerous disorders, including anxiety, depression, insomnia, asthma, pain, rheumatism, muscle spasms, and seizures. It suppresses emotional excitability and may produce a mild euphoria. Effects include analgesia, sedation, diminished reflexes, impaired gait, and pupil dilation. Kava has been used or studied most often for treatment of anxiety, stress, and restlessness. It is thought to act similarly to the benzodiazepines by interacting with gamma-aminobutyric acidA (GABAa) receptors on nerve cell membranes. This action and limited evidence from a few small clinical trials may support use of the herb in the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, and seizure disorders. However, additional studies are needed to delineate therapeutic and adverse effects, dosing recommendations, and drug interactions when used for these conditions.

Adverse effects include impaired thinking, judgment, motor reflexes, and vision. Serious adverse effects may occur with long-term, heavy use, including decreased plasma proteins, decreased platelet and lymphocyte counts, dyspnea, and pulmonary hypertension. Kava should not be taken concurrently with other central nervous system (CNS) depressant drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines, ethanol), antiplatelet drugs, or levodopa (increases Parkinson symptoms). In addition, it should not be taken by women who are pregnant or lactating or by children under 12 years of age. Finally, it should be used cautiously by patients with renal disease, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia. Recently, the U.S. FDA issued a warning that products containing kava have been implicated in many cases of severe liver toxicity (e.g., hepatitis, cirrhosis, liver failure).

Melatonin

This hormone is produced by the pineal gland, an endocrine gland in the brain. Endogenous melatonin is derived from the amino acid tryptophan, which is converted to serotonin, which is then enzymatically converted to melatonin in the pineal gland. Exogenous preparations are produced synthetically and may contain other ingredients. Melatonin products are widely available. Recommended doses on product labels usually range from 0.3 to 5 mg.

Melatonin influences sleep-wake cycles; it is released during sleep, and serum levels are very low during waking hours. Prolonged intake of exogenous melatonin can reset the sleep-wake cycle. As a result, it is widely promoted for prevention and treatment of jet lag (considered a circadian rhythm disorder) and treatment of insomnia. It is thought to act similarly to the benzodiazepines in inducing sleep. In several studies of patients with sleep disturbances, those taking melatonin experienced modest improvement compared with those taking a placebo. Other studies suggest that melatonin supplements improve sleep in older adults with melatonin deficiency and decrease weight loss in people with cancer. Large, controlled studies are needed to determine the effects of long-term use and the most effective regimen when used for jet lag.

Melatonin supplements are contraindicated in patients with hepatic insufficiency because of reduced clearance. They are also contraindicated in people with a history of cerebrovascular disease, depression, or neurologic disorders. They should be used cautiously by people with renal impairment and those taking benzodiazepines or other CNS depressant drugs. Adverse effects include altered sleep patterns, confusion, headache, hypothermia, pruritus, sedation, and tachycardia.

Valerian

This herb is used mainly as a sedative-hypnotic. It apparently increases the amount of GABA in the brain, probably by inhibiting the transaminase enzyme that normally metabolizes GABA. Increasing GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, results in calming, sedative effects.

There are differences of opinion about the clinical usefulness of valerian; some practitioners say that studies indicate the herb’s effectiveness as a sleep aid and mild antianxiety agent, whereas others say that these studies were flawed by small samples, short durations, and poor definitions of patient populations. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of valerian for treating insomnia.

Adverse effects with acute overdose or chronic use include blurred vision, cardiac disturbance, excitability, headache, hypersensitivity reactions, insomnia, and nausea. There is a risk of hepatotoxicity from overdosage and from using combination herbal products containing valerian. Valerian should not be taken by people with hepatic impairment (risk of increased liver damage) or by pregnant or breast-feeding women (effects are unknown). The herb should not be taken concurrently with any other sedatives, hypnotics, alcohol, or CNS depressants because of the potential for additive CNS depression.

Clinical Application 53-1

Mrs. Terrence’s two sons come to visit her in the hospital. They complain to the nurse that their mother seems oversedated. In denial about her mental status, the sons request that their mother’s medication be discontinued, but the nurses are concerned that if she is agitated, she may pull out her IV lines and Foley catheter as well as possibly strike out at staff. How does the nurse handle this situation while respecting the family’s concerns, based on his or her knowledge and skills of patient-centered care according to the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses project (QSEN)?

Mrs. Terrence’s two sons come to visit her in the hospital. They complain to the nurse that their mother seems oversedated. In denial about her mental status, the sons request that their mother’s medication be discontinued, but the nurses are concerned that if she is agitated, she may pull out her IV lines and Foley catheter as well as possibly strike out at staff. How does the nurse handle this situation while respecting the family’s concerns, based on his or her knowledge and skills of patient-centered care according to the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses project (QSEN)?

Nutritional and herbal supplements for anxiety and anxiety-related disorders

by S. LAKHAN, K. VIEIRA

Nutrition Journal 2010, 9(42), 1-14

Over the past several decades, complementary and alternative medications have increasingly become a part of everyday treatment. The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders is approximately 16% worldwide. Many people with these disorders consider the use of herbal and other natural treatments for the management of their psychological symptoms for various reasons, such as costs associated with prescriptions medications as well as the adverse effects associated with their use. This review included a total of 24 clinical studies published in English that used human subjects and examined the anxiolytic potential of dietary and herbal supplements.

The conclusion of this systematic review supports the use of nutritional and herbal supplements, such as kava, as an effective method for treating anxiety and anxiety-related conditions without the risk of serious adverse effects. However, more research is needed in this area due to potentially dangerous effects of over-consumption of supplements and adverse interactions with prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE: When caring for patients who are suffering from anxiety, it is imperative that nurses assess the patient’s use of herbal and complementary supplements administered for the treatment of anxiety. The U.S. FDA does not regulate complementary and alternative medications, and they can place the patient at risk for adverse effects when administered with prescribed anxiolytics, sedatives, or hypnotics.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are widely used for anxiety and insomnia and are also used for several other indications. These drugs have a wide margin of safety between therapeutic and toxic doses, and they are rarely fatal, even in overdose, unless combined with other CNS depressant drugs, such as alcohol. However, benzodiazepines are Schedule IV drugs under the Controlled Substances Act. Drugs of abuse, they may cause physiologic dependence; therefore, withdrawal symptoms occur if these drugs are stopped abruptly. To avoid withdrawal symptoms, it is necessary to taper benzodiazepines gradually before discontinuing them completely.

Although benzodiazepines are effective anxiolytics, long-term use is associated with concerns over tolerance, dependency, withdrawal, lack of efficacy for treating the depression that often accompanies anxiety disorders, and the need for multiple daily dosing with some agents. These drugs differ mainly in their plasma half-lives, production of active metabolites, and clinical uses.  Diazepam (Valium) is the prototype benzodiazepine.

Diazepam (Valium) is the prototype benzodiazepine.

Pharmacokinetics

Diazepam has a long half-life (20-80 hours) and forms an active metabolite that tends to accumulate. The drug requires 5 to 7 days to reach steady-state serum levels. It is highly lipid soluble, widely distributed in body tissues, and highly bound to plasma proteins (85%-98%). The high lipid solubility allows the drug to easily enter the CNS and perform its actions. After IV injection, diazepam may act within 1 to 5 minutes. However, the duration of action of a single IV dose is short (30-100 minutes). Thus, the pharmacodynamic effects (e.g., sedation) do not correlate with plasma drug levels because the drugs move in and out of the CNS rapidly. This redistribution allows a patient to awaken even though the drug may remain in the blood and other peripheral tissues for days or weeks before it is completely eliminated.

Diazepam is mainly metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP3A4 subgroup) and glucuronide conjugation. Metabolites are excreted through the kidneys.

Action

Diazepam enhances the inhibitory effect of GABA to relieve anxiety, tension, and nervousness and to produce sleep. The decreased neuronal excitability also accounts for its usefulness as a muscle relaxant, hypnotic, and anticonvulsant.

Use

Health care providers mainly use diazepam for antianxiety, hypnotic, and anticonvulsant purposes. They also give the drug for preoperative sedation; prevention of agitation and delirium tremens in acute alcohol withdrawal; and treatment of anxiety symptoms associated with depression, acute psychosis, or mania. Thus, patients often take it concurrently with antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers. However, use of diazepam contraindicates the use of some antidepressants. Experts do not advise using the drug for long periods, because it may cause excessive sedation and respiratory depression.

Investigators have extensively studied diazepam, and it has more approved uses than other drugs in its class. Table 53.2 gives route and dosage information for diazepam and the other benzodiazepines. Larger-than-usual doses may be necessary for patients who are severely anxious or agitated. Also, large doses are usually required to relax skeletal muscle; control muscle spasm; control seizures; and provide sedation before surgery, cardioversion, endoscopy, and angiography. When using benzodiazepines with opioid analgesics, it is important to reduce the analgesic dose initially and increase it gradually to avoid excessive CNS depression.

TABLE 53.2

TABLE 53.2Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree