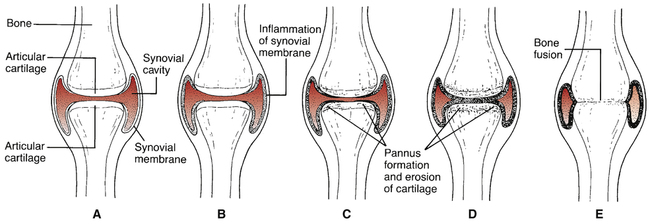

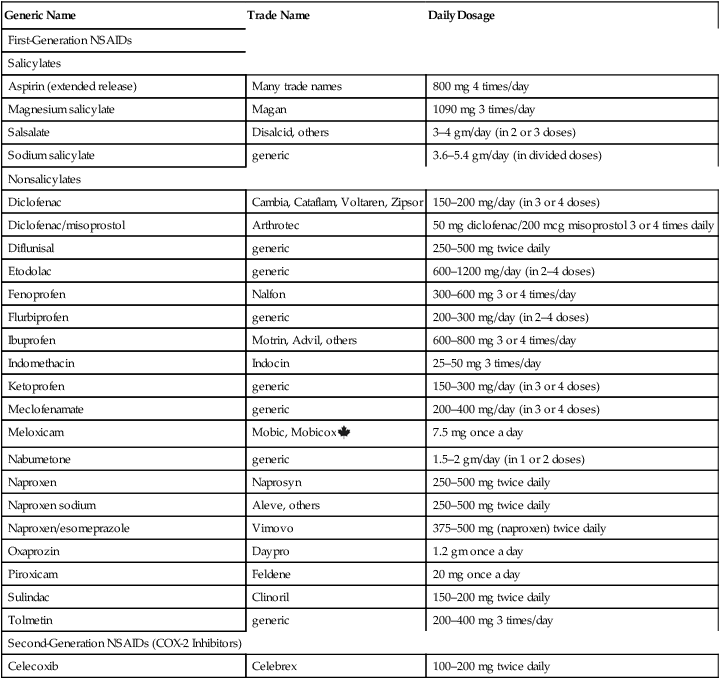

CHAPTER 73 The progression of joint deterioration is depicted in Figure 73–1. Inflammation begins in the synovium—the membrane that encloses the joint cavity. As inflammation intensifies, the synovial membrane thickens and begins to envelop the articular cartilage. This overgrowth is referred to as pannus. Damage to the cartilage is caused by enzymes released from the pannus and by chemicals and enzymes produced by the inflammatory process raging within the synovial space. Ultimately, the articular cartilage undergoes total destruction, resulting in direct contact between bones of the joint, followed by eventual bone fusion. After this, inflammation subsides. • Guidelines for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: 2002 Update, available online at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.10148/pdf • American College of Rheumatology 2008 Recommendations for the Use of Nonbiologic and Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs in Rheumatoid Arthritis, available online at http://www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/guidelines/recommendations.pdf The basic pharmacology of the NSAIDs is discussed in Chapter 71. Consideration here is limited to their role in RA. As discussed in Chapter 71, there are two main classes of NSAIDs: (1) first-generation NSAIDs, which inhibit COX-1 and COX-2; and (2) second-generation NSAIDs (coxibs), which selectively inhibit COX-2. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects result from inhibiting COX-2, whereas major adverse effects—especially gastroduodenal ulceration—result from inhibiting COX-1. Because of their selectivity, the coxibs may cause less GI ulceration than the first-generation NSAIDs, while producing equal therapeutic effects. Dosages employed for anti-inflammatory effects are considerably higher than those required for analgesia or fever reduction. For example, treatment of RA may require 5.2 gm (16 standard tablets) of aspirin a day, compared with only 2.6 gm for aches, pain, and fever. Dosages for RA are summarized in Table 73–1. TABLE 73–1 Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Oral Dosage for Rheumatoid Arthritis The glucocorticoids are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs that can relieve symptoms of severe RA, and may also retard disease progression. For patients with generalized symptoms, oral glucocorticoids are indicated. However, if only one or two joints are affected, intra-articular injections may be employed. Because long-term oral therapy can cause serious toxicity (eg, osteoporosis, gastric ulceration, adrenal suppression), short-term therapy should be used whenever possible. Most often, glucocorticoids are used for temporary relief until drugs with more slowly developing effects (eg, methotrexate) can provide control. Long-term therapy should be limited to patients who have failed to respond adequately to all other options. The most commonly employed oral glucocorticoids are prednisone and prednisolone. When symptoms flare, patients may be given 10 to 20 mg/day until symptoms are controlled, followed by gradual drug withdrawal over 5 to 7 days. The pharmacology of the glucocorticoids is discussed at length in Chapter 72 (Glucocorticoids in Nonendocrine Disorders). Methotrexate [Rheumatrex, Trexall] acts faster than all other DMARDs. Therapeutic effects may develop in 3 to 6 weeks. At least 80% of patients improve with this drug. Benefits are the result of immunosuppression secondary to reducing the activity of B and T lymphocytes. Many rheumatologists consider methotrexate the DMARD of first choice, owing to its efficacy, relative safety, low cost, and extensive use in RA. Major toxicities are hepatic fibrosis, bone marrow suppression, GI ulceration, and pneumonitis. Periodic tests of liver and kidney function are mandatory, as are complete blood cell and platelet counts. Methotrexate can cause fetal death and congenital abnormalities, and therefore is contraindicated during pregnancy. Recent data suggest that patients using methotrexate for RA may have a reduced life expectancy, owing to increased deaths from cardiovascular disease, infection, and certain cancers (melanoma, lung cancer, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma). For treatment of RA, methotrexate is administered once a week, either orally or by injection. Oral dosage is 10 to 15 mg/wk initially, and then increased by 5 mg/wk every 2 to 4 weeks, up to a maintenance level of 20 to 30 mg/wk. Dosing with folic acid (at least 5 mg/wk) is recommended to reduce GI and hepatic toxicity. Methotrexate is discussed at length in Chapter 102 (Anticancer Drugs I: Cytotoxic Agents). Sulfasalazine [Azulfidine, Azulfidine EN-tabs] has been used for decades to treat inflammatory bowel disease (see Chapter 80) and is now used for RA too. Benefits may result from anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions. In patients with RA, sulfasalazine can slow the progression of joint deterioration, sometimes with just 1 month of treatment. Gastrointestinal reactions (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, abdominal pain) are the most common reasons for stopping treatment. These reactions can be minimized by using an enteric-coated formulation and by dividing the daily dosage. Dermatologic reactions (pruritus, rash, urticaria) are also common. Fortunately, serious adverse effects—hepatitis and bone marrow suppression—are rare. To ensure early detection, periodic monitoring for hepatitis and bone marrow function (complete blood counts, platelet counts) should be performed. Because of its structure, sulfasalazine should not be given to patients with sulfa allergy. The initial dosage for RA is 1000 mg/day. The usual maintenance dosage is 1000 mg 2 or 3 times a day. Sulfasalazine is discussed further in Chapter 80 (Other Gastrointestinal Drugs).

Drug therapy of rheumatoid arthritis

Pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis

Progressive joint degeneration in rheumatoid arthritis.

Progressive joint degeneration in rheumatoid arthritis.

A, Healthy joint. B, Inflammation of synovial membrane. C, Onset of pannus formation and cartilage erosion. D, Pannus formation progresses and cartilage deteriorates further. E, Complete destruction of joint cavity together with fusion of articulating bones.

Overview of therapy

Drug therapy

Drug selection

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NSAID classification.

Dosage.

Generic Name

Trade Name

Daily Dosage

First-Generation NSAIDs

Salicylates

Aspirin (extended release)

Many trade names

800 mg 4 times/day

Magnesium salicylate

Magan

1090 mg 3 times/day

Salsalate

Disalcid, others

3–4 gm/day (in 2 or 3 doses)

Sodium salicylate

generic

3.6–5.4 gm/day (in divided doses)

Nonsalicylates

Diclofenac

Cambia, Cataflam, Voltaren, Zipsor

150–200 mg/day (in 3 or 4 doses)

Diclofenac/misoprostol

Arthrotec

50 mg diclofenac/200 mcg misoprostol 3 or 4 times daily

Diflunisal

generic

250–500 mg twice daily

Etodolac

generic

600–1200 mg/day (in 2–4 doses)

Fenoprofen

Nalfon

300–600 mg 3 or 4 times/day

Flurbiprofen

generic

200–300 mg/day (in 2–4 doses)

Ibuprofen

Motrin, Advil, others

600–800 mg 3 or 4 times/day

Indomethacin

Indocin

25–50 mg 3 times/day

Ketoprofen

generic

150–300 mg/day (in 3 or 4 doses)

Meclofenamate

generic

200–400 mg/day (in 3 or 4 doses)

Meloxicam

Mobic, Mobicox ![]()

7.5 mg once a day

Nabumetone

generic

1.5–2 gm/day (in 1 or 2 doses)

Naproxen

Naprosyn

250–500 mg twice daily

Naproxen sodium

Aleve, others

250–500 mg twice daily

Naproxen/esomeprazole

Vimovo

375–500 mg (naproxen) twice daily

Oxaprozin

Daypro

1.2 gm once a day

Piroxicam

Feldene

20 mg once a day

Sulindac

Clinoril

150–200 mg twice daily

Tolmetin

generic

200–400 mg 3 times/day

Second-Generation NSAIDs (COX-2 Inhibitors)

Celecoxib

Celebrex

100–200 mg twice daily

Glucocorticoids

Nonbiologic (traditional) DMARDs

Methotrexate

Sulfasalazine

Drug therapy of rheumatoid arthritis

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access