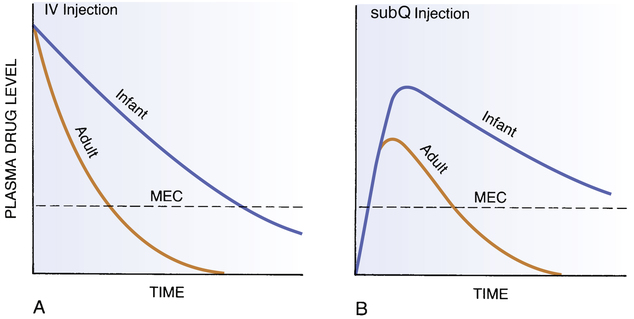

CHAPTER 10 Patients who are very young or very old respond differently to drugs than do the rest of the population. Most differences are quantitative. Specifically, patients in both age groups are more sensitive to drugs than other patients, and they show greater individual variation. Drug sensitivity in the very young results largely from organ system immaturity. Drug sensitivity in the elderly results largely from organ system degeneration. Because of heightened drug sensitivity, patients in both age groups are at increased risk of adverse drug reactions. In this chapter we discuss the physiologic factors that underlie heightened drug sensitivity in pediatric patients, as well as ways to promote safe and effective drug use. Drug therapy in geriatric patients is discussed in Chapter 11. • Premature infants (less than 36 weeks’ gestational age) • Full-term infants (36 to 40 weeks’ gestational age) • Neonates (first 4 postnatal weeks) • Infants (weeks 5 to 52 postnatal) • About 20% were ineffective in children, even though they were effective in adults. • About 30% caused unanticipated side effects, some of them potentially lethal. • About 20% required dosages different from those that had been extrapolated from dosages used in adults. As we discussed in Chapter 4, pharmacokinetic factors determine the concentration of a drug at its sites of action, and hence determine the intensity and duration of responses. If drug levels are elevated, responses will be more intense. If drug elimination is delayed, responses will be prolonged. Because the organ systems that regulate drug levels are not fully developed in the very young, these patients are at risk of both possibilities: drug effects that are unusually intense and prolonged. By accounting for pharmacokinetic differences in the very young, we can increase the chances that drug therapy will be both effective and safe. Figure 10–1 illustrates how drug levels differ between infants and adults following administration of equivalent doses (ie, doses adjusted for body weight). When a drug is administered intravenously (Fig. 10–1A), levels decline more slowly in the infant than in the adult. As a result, drug levels in the infant remain above the minimum effective concentration (MEC) longer than in the adult, thereby causing effects to be prolonged. When a drug is administered subcutaneously (Fig. 10–1B), not only do levels in the infant remain above the MEC longer than in the adult, but these levels also rise higher, causing effects to be more intense as well as prolonged. From these illustrations, it is clear that adjustment of dosage for infants on the basis of body size alone is not sufficient to achieve safe results.

Drug therapy in pediatric patients

Pharmacokinetics: neonates and infants

Comparison of plasma drug levels in adults and infants.

Comparison of plasma drug levels in adults and infants.

A, Plasma drug levels following IV injection. Dosage was adjusted for body weight. Note that plasma levels remain above the minimum effective concentration (MEC) much longer in the infant. B, Plasma drug levels following subQ injection. Dosage was adjusted for body weight. Note that both the maximum drug level and the duration of action are greater in the infant. (Redrawn from Levine RR: Pharmacology: Drug Actions and Reactions. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973:238.)

Drug therapy in pediatric patients

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access