Describe the types of immunity and the agents that produce them.

Identify immunizations recommended for children and adolescents.

Identify immunizations recommended for children and adolescents.

Identify immunizations recommended for adults.

Identify immunizations recommended for adults.

Identify authoritative sources for immunization information.

Identify authoritative sources for immunization information.

Be able to teach parents (and their children) about the importance of immunizations to public health.

Be able to teach parents (and their children) about the importance of immunizations to public health.

Be able to teach people about recommended immunizations and record keeping.

Be able to teach people about recommended immunizations and record keeping.

Clinical Application Case Study

Cynthia Williams, a 26-year-old college student, brings her 15-month-old son Riley to a family practice clinic for a well-child checkup. Mrs. Williams says that Riley has had his previous immunizations at the county health department every 2 months until the age of 6 months but that he has not had any immunizations since then.

KEY TERMS

Active immunity: antigenic immune response with antibody formation to an infection through administration of a vaccine or toxoid or through natural exposure to the disease

Antigenicity: ability of an antigen to bind specifically with certain products to promote better antibody formation

Immunization: bolstering a person’s immune system by inducing antibody formation, thereby providing active protection against a specific infectious disease

Passive immunity: temporary state of immunity produced in a person who is susceptible to an infectious organism by administering serum containing antibodies to the disease

Toxoids: altered bacterial toxins that are administered to stimulate antitoxin production and protect against the harmful effects of the toxin

Vaccines: microorganisms or components of microorganisms that are administered to stimulate antibody production against the microorganism prior to a natural infection

Introduction

Immunization, which involves bolstering a person’s immune system by inducing antibody formation, thereby providing active protection against a specific infectious disease, has greatly improved human health and life expectancy. Immunizations are one of the key factors in reducing mortality and improving life expectancy in the United States over the past century. Worldwide, some infections such as smallpox and polio have almost been eradicated as a result of effective immunization programs. The nurse plays a pivotal role in this process of assessing, teaching, administering immunizations, and evaluating patients who have received them for adverse effects.

Overview of Immunization

Types of Immunity

There are two main types of immunity. Active immunity results from administering a dead or weakened microorganism or piece of the microorganism to a person. The person’s immune system responds by producing immunoglobulins (antibodies) specific for that microorganism, providing protection against disease with later exposure. Passive immunity results from parenteral administration of immune serum containing disease-specific antibodies to a nonimmune person. Passive immunity is only temporary, and the person still needs a vaccine against a specific disease to develop antibodies that provide long-term immunity. Preparations used for immunization are biologic products prepared by pharmaceutical companies and are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Widespread use of these products in the United States has dramatically decreased the incidence of many infectious diseases, such as polio, influenza, pneumococcal disease, and hepatitis B.

Kinds of Immunizing Agents

Agents for Active Immunity

The biologic products used for active immunity are vaccines and toxoids. For maximum effectiveness, both of these products must be given before exposure to the pathogenic microorganism. Administration by the recommended route helps ensure the desired immunologic response.

Vaccines are suspensions of microorganisms or their antigenic products that have been killed (inactivated) or attenuated (weakened or reduced in virulence) so they can induce antibody formation while preventing infection altogether or causing only a very mild form of it. Many vaccines produce long-lasting immunity. Attenuated live vaccines produce active immunity, usually lifelong, that is similar to that produced by natural infection. There is a small risk that live vaccines may produce disease in people with severely impaired immune function, but this risk is very low with new vaccines developed using recombinant DNA technology.

Toxoids are bacterial toxins or products that have been modified to destroy toxicity while retaining antigenic properties (i.e., ability to induce antibody formation). Immunization with toxoids is not permanent, and scheduled repeat doses (boosters) are required to maintain immunity.

Additional components, such as aluminum or calcium phosphate, are added to some vaccines and toxoids, to slow absorption and increase antigenicity (ability of an antigen to bind specifically with certain products to promote better antibody formation). Products containing aluminum can only be given intramuscularly because greater tissue irritation occurs with subcutaneous injections of the immunizing agent.

In general, vaccines and toxoids are quite safe, and risks of the diseases they prevent are significantly greater than the risks of the vaccines. However, risks and benefits of vaccination are always considered individually, because no vaccine is completely effective or completely safe. A few people may still develop a disease after being immunized against it. However, if this happens, symptoms are usually less severe and complications are fewer than if the person had not been immunized. Adverse vaccine effects are usually mild and of short duration. The FDA evaluates vaccine safety before and after a vaccine is marketed, although some adverse effects become apparent only after a vaccine is used in a large population.

Agents for Passive Immunity

Immune serums are the biologic products used for passive immunity. They act rapidly to provide temporary immunity lasting about 1 to 3 months in people exposed to or experiencing an infectious disease. The goal of therapy is to prevent or modify the disease process (i.e., decrease the incidence and severity of symptoms).

Immune globulin products are made from the serum of people with high concentrations of the specific antibody or immunoglobulin required. These products may consist of whole serum or only contain the immunoglobulin portion of serum in which the specific antibodies are concentrated. Immunoglobulin fractions are preferred over whole serum because they are more likely to be effective in disease prevention. All plasma used to prepare these products is screened for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Hyperimmune serums are available for cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B, rabies, rubella, tetanus, varicella-zoster (shingles), and respiratory syncytial virus infections.

Individual Immunizing Agents

Box 10.1 provides information about current recommendations for immunizations. Table 10.1 lists vaccines and toxoids that are used routinely in the United States, and Table 10.2 lists immune serums that are used regularly in this country.

BOX 10.1 Recommended Immunizations by Age Group

Children and Adolescents

Rotavirus vaccine (RotaTeq) or (Rotarix) started at age 6 weeks through 14 weeks of age to protect infants against rotavirus gastroenteritis. RotaTeq consists of two vaccine doses 2 months apart, with a third dose of Rotarix is recommended at age 6 months.

Rotavirus vaccine (RotaTeq) or (Rotarix) started at age 6 weeks through 14 weeks of age to protect infants against rotavirus gastroenteritis. RotaTeq consists of two vaccine doses 2 months apart, with a third dose of Rotarix is recommended at age 6 months.

A single booster dose of tetanus and diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) for adolescents and adults because protection against pertussis declines a few years after initial immunization with pertussis vaccine during early childhood. The Tdap booster is recommended 5 years after the last Td immunization. Boostrix is used for people 10 to 18 years of age, and Adacel is used for people 11 to 64 years of age.

A single booster dose of tetanus and diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) for adolescents and adults because protection against pertussis declines a few years after initial immunization with pertussis vaccine during early childhood. The Tdap booster is recommended 5 years after the last Td immunization. Boostrix is used for people 10 to 18 years of age, and Adacel is used for people 11 to 64 years of age.

Four doses of pneumococcal vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar) for healthy young children

Four doses of pneumococcal vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar) for healthy young children

Two doses of chickenpox vaccine (e.g., Varivax), with the first dose at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years of age. Chickenpox vaccine is also recommended for adolescents and nonpregnant adults who have never had chickenpox or been vaccinated previously with a single dose; two doses of vaccine are required for full immunity.

Two doses of chickenpox vaccine (e.g., Varivax), with the first dose at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years of age. Chickenpox vaccine is also recommended for adolescents and nonpregnant adults who have never had chickenpox or been vaccinated previously with a single dose; two doses of vaccine are required for full immunity.

A combined vaccine for measles, mumps, rubella, and chickenpox (ProQuad) for children aged 12 months to 12 years. Another vaccine combination (Pentacel), which contains diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and H. influenzae type b (Hib), can be used for primary immunization in infancy as well as for booster doses. Combination vaccines are recommended for use in children who need multiple vaccines at a single visit.

A combined vaccine for measles, mumps, rubella, and chickenpox (ProQuad) for children aged 12 months to 12 years. Another vaccine combination (Pentacel), which contains diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and H. influenzae type b (Hib), can be used for primary immunization in infancy as well as for booster doses. Combination vaccines are recommended for use in children who need multiple vaccines at a single visit.

Hepatitis A vaccination for all children in the United States, with the first of two doses between 1 and 2 years of age

Hepatitis A vaccination for all children in the United States, with the first of two doses between 1 and 2 years of age

Annual flu vaccination for all people older than 6 months of age. Infants younger than 2 years of age and all children and adults with underlying medical conditions should receive the trivalent inactive vaccine (TIV). The live attenuate influenza vaccine (LAIV; FluMist) should be used only for nonpregnant people between 2 and 49 years of age who are healthy and not at high risk for influenza complications. Two vaccine doses at least 4 weeks apart should be given to children younger than 9 years of age.

Annual flu vaccination for all people older than 6 months of age. Infants younger than 2 years of age and all children and adults with underlying medical conditions should receive the trivalent inactive vaccine (TIV). The live attenuate influenza vaccine (LAIV; FluMist) should be used only for nonpregnant people between 2 and 49 years of age who are healthy and not at high risk for influenza complications. Two vaccine doses at least 4 weeks apart should be given to children younger than 9 years of age.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil) for all adolescents 11 or 12 years of age (can be given as early as 9 years) or up to 26 years of age if not received earlier. Bivalent HPV2 vaccine (Cervarix) can be given to females 9 through 26 years of age. Both vaccines are most effective if given before the person becomes sexually active.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil) for all adolescents 11 or 12 years of age (can be given as early as 9 years) or up to 26 years of age if not received earlier. Bivalent HPV2 vaccine (Cervarix) can be given to females 9 through 26 years of age. Both vaccines are most effective if given before the person becomes sexually active.

Meningococcal vaccine administration at 11 or 12 years of age with a booster dose at age 16 years. If not received earlier, two doses at least 8 weeks apart are recommended for adolescents up to age 21.

Meningococcal vaccine administration at 11 or 12 years of age with a booster dose at age 16 years. If not received earlier, two doses at least 8 weeks apart are recommended for adolescents up to age 21.

Adults

Chickenpox vaccine for adults who never had the disease or vaccine; a second dose of vaccine for adults who previously received a single dose

Chickenpox vaccine for adults who never had the disease or vaccine; a second dose of vaccine for adults who previously received a single dose

HPV vaccine in adults up to age 26 years, if not previously received

HPV vaccine in adults up to age 26 years, if not previously received

Tdap booster vaccine (e.g., Adacel) once for all adults younger than 65 years of age, especially health professionals and those who have close contact with infants (younger than 1 year of age)

Tdap booster vaccine (e.g., Adacel) once for all adults younger than 65 years of age, especially health professionals and those who have close contact with infants (younger than 1 year of age)

The pneumococcal vaccine, Pneumovax, for smokers and people with asthma or other chronic conditions who are between 19 and 64 years of age

The pneumococcal vaccine, Pneumovax, for smokers and people with asthma or other chronic conditions who are between 19 and 64 years of age

Zoster vaccine (Zostavax) (to prevent herpes zoster [shingles]) in adults 60 years and older

Zoster vaccine (Zostavax) (to prevent herpes zoster [shingles]) in adults 60 years and older

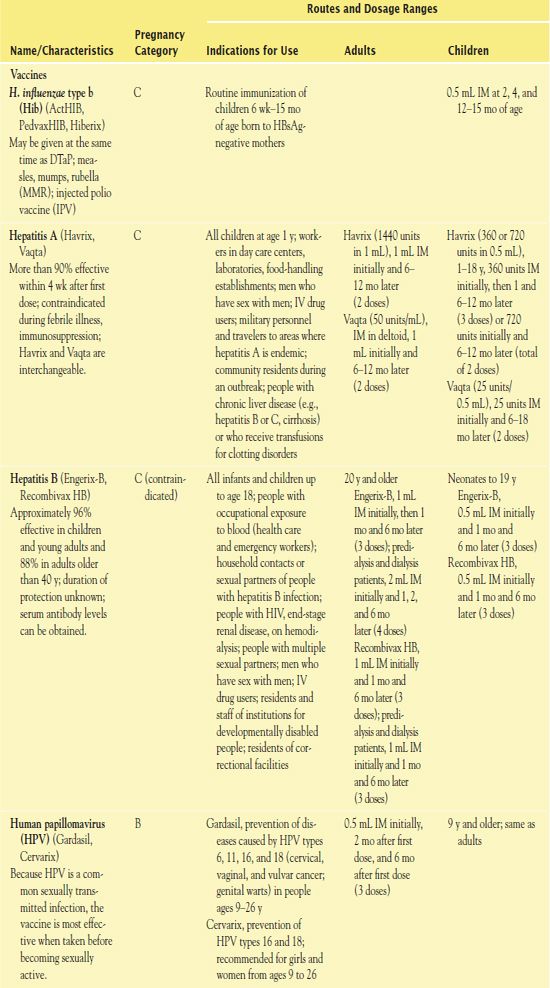

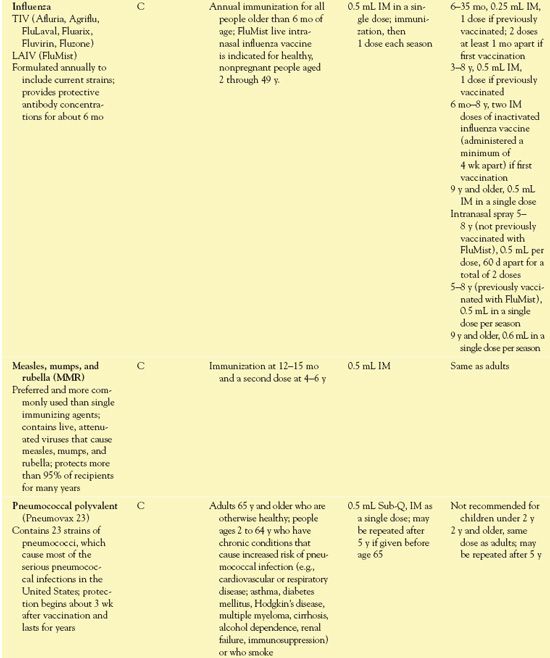

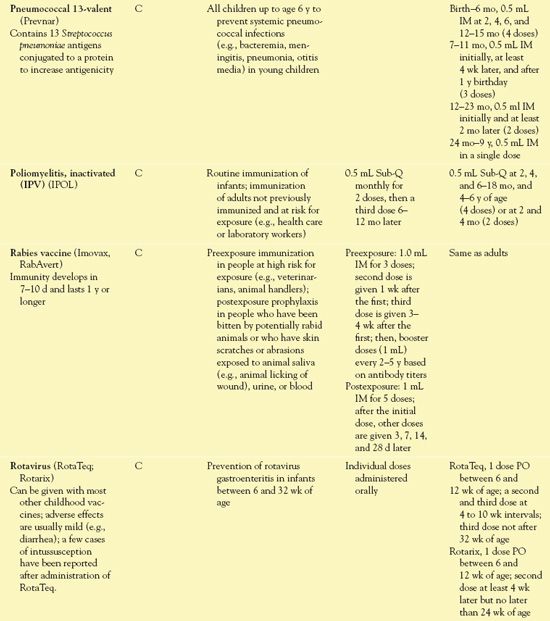

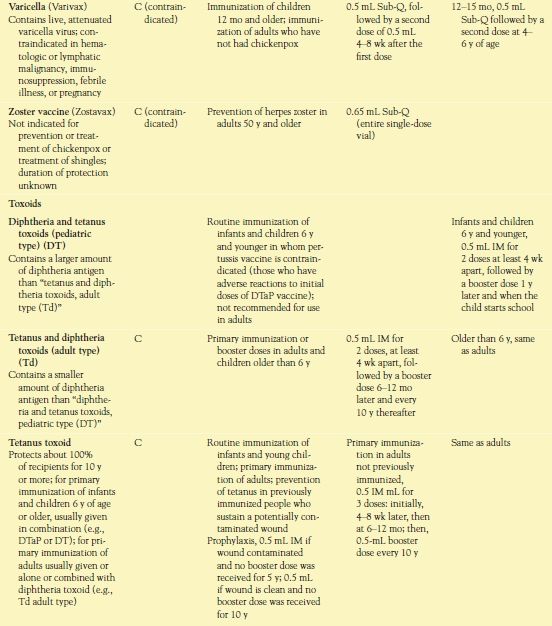

TABLE 10.1

TABLE 10.1

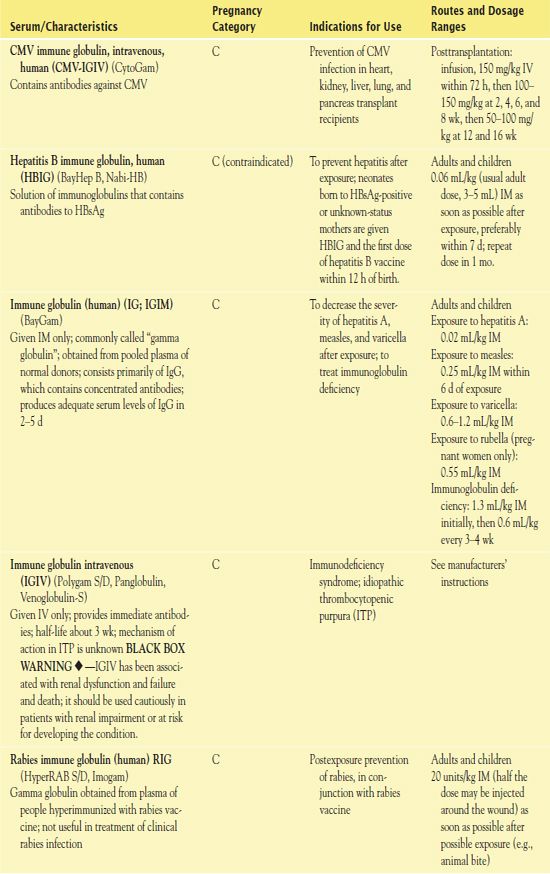

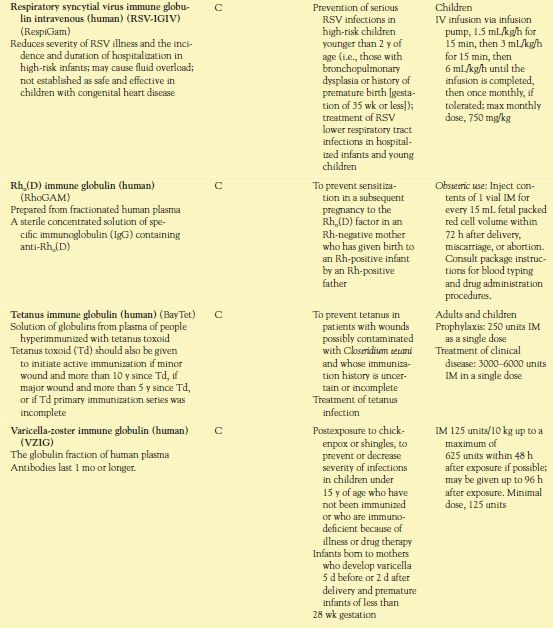

TABLE 10.2

TABLE 10.2

CMV, cytomegalovirus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

Use

Clinical indications for vaccines and toxoids include the following:

• Routine immunization of children against diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type b infection, hepatitis A and B, influenza, measles (rubeola), mumps, pertussis, pneumococcal infection, poliomyelitis, rotavirus, rubella (German measles), tetanus, and varicella (chickenpox)

• Routine immunization of adolescents and adults against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (Tdap); varicella, if immunity not established; as well as influenza annually

• Immunization of prepubertal girls or women of child-bearing age against rubella.

QSEN Safety Alert

Rubella during the first trimester of pregnancy is associated with a high incidence of birth defects in the newborn.

• Immunization of people at high risk for serious morbidity or mortality from a chronic condition. For example, pneumococcal vaccine is recommended in people 65 years of age and older, as well as in people younger than 65 years of age with chronic diseases.

• Immunization of adults and children at high risk for a particular disease. For example, pneumococcal vaccine is recommended for people older than 2 years of age who have chronic respiratory disease or have had a splenectomy. Also, administration of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is recommended in young adolescents to prevent genital warts and the risk of cervical cancer.

Use in Children

Routine immunization of children has reduced the prevalence of many common childhood diseases (listed previously; e.g., diphtheria, measles [rubeola], mumps, pertussis, and varicella [chickenpox]), and immunization rates have increased in recent years. By 4 to 6 years of age, children should have received vaccinations against these diseases. Because some vaccines are administered more than once, a child may receive more than 20 injections by 2 years of age. Two strategies to increase immunizations are the use of combination vaccines and the administration of multiple vaccines (in separate syringes and at different sites) at one visit to a health care provider whenever feasible. Combination vaccines decrease the number of injections, and giving multiple vaccines at one visit decreases the number of visits to a health care provider. Several combination vaccines are now available (Box 10.2), and others continue to be developed. Studies indicate that these strategies are effective in improving rates of immunizations. Children’s health care providers should implement the recommended childhood immunization schedule issued in January of each year by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Also, they should refer to current guidelines about immunizations for children with chronic illnesses (e.g., asthma, heart disease, diabetes) or immunosuppression (e.g., from cancer, organ transplantation, or human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection).

BOX 10.2 Combination Vaccines Used for Routine Childhood Immunizations

DTaP-IPV (Kinrix)

DTaP-Hep B-IPV (Pediarix)

DTaP-IPV-Hib (Pentacel)

DTaP-Hib (TriHIBit)

Hib-Hep B (Comvax)

Hep A-Hep B (Twinrix)

MMR-Var (ProQuad)

Vaccine-preventable Diseases, Immunizations, and MMWR 1961–2011.

by HINMAN, A. R., ORENSTEIN, W. A., & SCHICHAT, A.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2011, 60(4 Suppl), 49-57

In the 50 years since the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has been reporting morbidity and mortality reports, the awareness of diseases now prevented by vaccines has been expanded, new vaccines have been introduced, the incidence of most of these diseases has been dramatically reduced, and some unanticipated challenges have emerged. Three periods (1961-1988, 1989-1999, and 2000-2010) categorize the improvements from immunizations have brought to the United States.

• 1961 to 1988: A nationwide immunization program was initiated. Children in the United States at the start of 1961 received vaccines to prevent five diseases: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, and smallpox. In this period, increased development of new vaccines lead to a reduction of disease.

• 1989 to 1999: A measles outbreak fundamentally changed the immunization program in the United States and prompted efforts to initiate comprehensive state- and community-based immunization action plans that identified the steps needed during the first 2 years of life. The goal was to achieve at least 90% immunization coverage of preschoolaged children for all recommended vaccines at the recommended ages. This led to immunization schedules that included the addition of several new vaccines, resulting in fewer outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

• 2000 to 2010: During this decade, disease was substantially reduced within the vaccination-targeted age groups, plus within unvaccinated populations. Immunization coverage for the infant vaccination series (DTaP—inactivated polio vaccine—MMR—Hib—hepatitis B—varicella) neared the Healthy People 2010 target of 80%. Vaccine-preventable diseases declined. The CDC reported that direct and indirect savings to society are estimated to total $69 billion. Advances in immunization information systems (IIS, immunization registries) enhanced confidentiality and coordination with population-based, computerized databases that record all vaccine doses administered by participating providers to people residing within a given geopolitical area; these systems are now in place in 48 of 50 states. Now children receive vaccines to prevent 16 conditions: diphtheria; H. influenzae type b, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and human papillomavirus infections; and influenza, measles, meningococcal disease, mumps, pertussis, pneumococcal disease, poliomyelitis, rotavirus infections, rubella, tetanus, and varicella.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree