Identify types of seizures as well as the potential causes and pathophysiology of seizures.

Identify factors that influence the choice of antiepileptic medications in treating seizure disorders.

Identify factors that influence the choice of antiepileptic medications in treating seizure disorders.

Identify the prototypes and describe the actions, uses, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for antiepileptic drugs in all classes.

Identify the prototypes and describe the actions, uses, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for antiepileptic drugs in all classes.

Describe strategies for prevention and treatment of status epilepticus.

Describe strategies for prevention and treatment of status epilepticus.

Implement the nursing process in the care of patients undergoing drug therapy for seizure disorders.

Implement the nursing process in the care of patients undergoing drug therapy for seizure disorders.

Discuss the common symptoms and disorders for which skeletal muscle relaxants are used.

Discuss the common symptoms and disorders for which skeletal muscle relaxants are used.

Identify the prototypes and describe the actions, uses, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the skeletal muscle relaxants.

Identify the prototypes and describe the actions, uses, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the skeletal muscle relaxants.

Implement the nursing process in the care of patients undergoing drug therapy for muscle spasms and spasticity.

Implement the nursing process in the care of patients undergoing drug therapy for muscle spasms and spasticity.

Clinical Application Case Study

Two days ago, Andrew Cummings, a 7-year-old boy, was at home playing and experienced a tonic–clonic seizure, which was witnessed by his mother. On questioning the mother, a pediatric neurologist at the hospital where the boy was admitted determined that the seizure was unprovoked and had a generalized onset. The mother stated that it lasted approximately 3 minutes. The neurologist diagnoses a seizure disorder. Andrew is now taking carbamazepine (Tegretol) 50 mg orally four times per day and sodium valproate (Depakene Syrup) 20 mg/kg/d.

KEY TERMS

Antiepileptic drugs: drugs used to control seizures or convulsions; also referred to as antiseizure medications or anticonvulsants

Clonic: spasms that alternate between contraction and relaxation

Convulsion: tonic–clonic type of seizure characterized by spasmodic contractions of involuntary muscles

Epilepsy: disease where the patient has repetitive seizures

Gingival hyperplasia: overgrowth of the gums related to long-term administration of phenytoin

Malignant hyperthermia: rare but life-threatening complication of anesthesia characterized by hypercarbia, metabolic acidosis, skeletal muscle rigidity, fever, and cyanosis

Monotherapy: use of a single drug in drug therapy; advantages include fewer drug–drug interactions, lower cost, and usually greater patient adherence

Muscle spasm: sudden, involuntary, painful muscle contraction that occurs with musculoskeletal trauma or inflammation

Seizure: brief episode of abnormal electrical activity in nerve cells of the brain that may or may not be accompanied by visible changes in appearance or behavior

Spasticity: caused by nerve damage in the brain and spinal cord, it is a permanent condition that may be painful and disabling; involves increased muscle tone or contraction and stiff, awkward movements

Status epilepticus: repeated seizures or a seizure that lasts at least 30 minutes; may be convulsive, nonconvulsive, or partial

Tonic: muscle spasms with sustained contraction

Tonic–clonic: most common type of seizure; often referred to as a major motor seizure

Tonic phase: sustained contraction of skeletal muscles; abnormal postures, such as opisthotonos; and absence of respirations, during which the person becomes cyanotic

Tonic phase: sustained contraction of skeletal muscles; abnormal postures, such as opisthotonos; and absence of respirations, during which the person becomes cyanotic

Clonic phase: rapid rhythmic and symmetric jerking movements of the body

Clonic phase: rapid rhythmic and symmetric jerking movements of the body

Introduction

The first part of this chapter introduces the condition known as epilepsy, which is characterized by recurrent seizures, and discusses the pharmacological care of the patient who is experiencing a seizure. Although the terms seizure and convulsion may be used interchangeably, they have different meanings. A seizure involves a brief episode of abnormal electrical activity in nerve cells of the brain that may or may not be accompanied by visible changes in appearance or behavior. It refers to all types of epileptic occurrences. A convulsion is a tonic–clonic type of seizure characterized by spasmodic contractions of involuntary muscles.

The second part of this chapter describes the role skeletal muscle relaxants play in decreasing seizures and reducing muscle spasms and spasticity associated with neurological and musculoskeletal injuries. A muscle spasm is a sudden, involuntary, painful muscle contraction that occurs with musculoskeletal trauma (e.g., overuse or injury of skeletal muscle, twisting a joint, or tearing a ligament as with a sprain) or inflammation (e.g., bursitis, arthritis). Muscle spasm also occurs with acute and chronic low back pain. Spasms may be clonic (alternating contraction and relaxation) to tonic (sustained contraction). Muscle spasms commonly occur, sometimes causing significant disability with inflammation, edema, and poor coordination and mobility.

Spasticity involves increased muscle tone or contraction and stiff, awkward movements. It occurs in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, cerebral palsy, and poststroke syndrome. Because spasticity is caused by nerve damage in the brain and spinal cord, it is a permanent condition that may be painful and disabling.

In patients with spinal cord injury, spasticity requires treatment when it impairs safety, mobility, and the ability to perform activities of daily living (e.g., self-care in hygiene, eating, dressing, and work or recreational activities). Stimuli that precipitate spasms vary from one individual to another and may include muscle stretching, bladder infections or stones, constipation and bowel distention, or infections. It is necessary to assess each person for personal precipitating factors, so that these factors can be avoided if possible. Treatment measures include passive range-of-motion and muscle-stretching exercises and antispasmodic medications (e.g., baclofen, dantrolene).

Overview of Epilepsy

Sudden, abnormal, hypersynchronous firing of neurons is characteristic of epilepsy. Signs and symptoms of seizure activity lead to the diagnosis. On the electroencephalogram (EEG), abnormal brain wave patterns are present.

Etiology

Seizures may occur as single events in response to hypoglycemia, fever, electrolyte imbalances, overdoses of numerous medications (e.g., amphetamine, cocaine, isoniazid, lidocaine, lithium, methylphenidate, antispasmodics, theophylline), and withdrawal from alcohol or sedative–hypnotic drugs. Alternatively, seizures may be idiopathic (having no discernible cause) or attributable to a secondary cause. Authorities also classify seizures as unprovoked (idiopathic) or provoked (secondary). Secondary causes in infancy include developmental defects, metabolic disease, or birth injury. Fever is a common secondary cause in late infancy and early childhood. Inherited forms of epilepsy usually begin in childhood or adolescence. When epilepsy begins in adulthood, it is often caused by an acquired neurologic disorder (e.g., head injury, stroke, brain tumor) or alcohol and other drug effects. Toxemia is a secondary cause of seizures in pregnancy.

Some of the identified specific causes of seizures include alterations in cell membrane permeability or the distribution of ions across the neuronal cell membranes. Genetic mutations have also been linked to epilepsy. In addition, a decrease in the inhibition of thalamic or cortical neuronal activity is a cause. Finally, imbalances in the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) or acetylcholine excess result in seizure disorders (Porth & Matfin, 2009).

Pathophysiology

Experts broadly classify seizures as partial or generalized. Partial seizures begin in a specific area of the brain and often indicate a localized brain lesion such as birth injury, trauma, stroke, or tumor. They produce symptoms ranging from simple motor and sensory manifestations to more complex abnormal movements and bizarre behavior. Movements are usually automatic, repetitive, and inappropriate to the situation, such as chewing, swallowing, or aversive movements (automatisms). In simple partial seizures, consciousness is not impaired; in complex partial seizures, the level of consciousness is decreased.

Clinical Manifestations

Generalized seizures are bilateral and symmetric and have no discernible point of origin in the brain. The most common type is the tonic–clonic or major motor seizure. The tonic phase involves sustained contraction of skeletal muscles; abnormal postures, such as opisthotonos; and absence of respiration, during which the person becomes cyanotic. The clonic phase is characterized by rapid rhythmic and symmetric jerking movements of the body. Tonic–clonic seizures are sometimes preceded by an aura—a brief warning, such as a flash of light or a specific sound or smell. In children, febrile seizures (i.e., tonic–clonic seizures that occur with fever in the absence of other identifiable causes) are the most common form of epilepsy.

The absence seizure, which is characterized by abrupt alterations in consciousness that last only a few seconds, is a kind of generalized seizure. Other types of generalized seizures include the myoclonic type (contraction of a muscle or group of muscles) and the akinetic type (absence of movement). Some people are subject to mixed seizures.

Status epilepticus is a life-threatening emergency characterized by generalized tonic–clonic convulsions lasting for several minutes or occurring at close intervals. During this time, the patient does not regain consciousness. Hypotension, hypoxia, and cardiac dysrhythmias may also occur. There is a high risk of permanent brain damage and death unless prompt, appropriate treatment is instituted. In a person taking medications for a diagnosed seizure disorder, the most common cause of status epilepticus is abruptly stopping antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). In other patients, regardless of whether they have a diagnosed seizure disorder, causes of status epilepticus include brain trauma or tumors, systemic or central nervous system (CNS) infections, alcohol withdrawal, and overdoses of drugs (e.g., cocaine, theophylline).

Drug Therapy

Treatment of the underlying cause or use of an AED may relieve seizures. AEDs can usually control seizure activity but do not cure the underlying disorder. Numerous difficulties, for both clinicians and patients, have been associated with AED therapy, including trials of different drugs; consideration of monotherapy (using a single drug) versus combination therapy (using two or more drugs); the need to titrate dosage over time; lack of seizure control while drugs are being selected and dosages adjusted; social stigma and adverse drug effects, often leading to poor patient adherence; and undesirable drug interactions among AEDs and between AEDs and other medications.

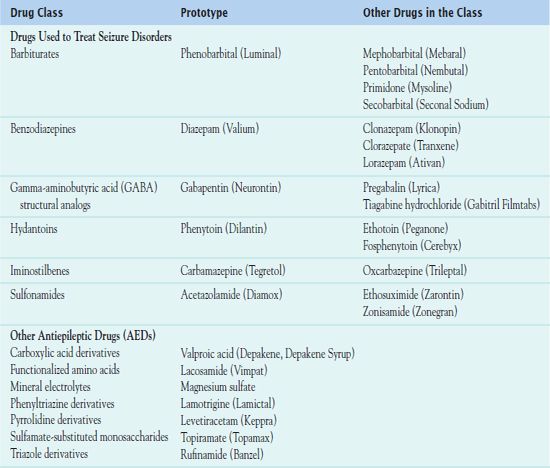

The AEDs used in the prevention and treatment of seizures has evolved over the years. In recent years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved newer medications in the treatment of seizure disorders. The FDA most often classifies these medications as newer or miscellaneous drugs. The medication tables identify the newer drugs primarily as derivatives. Table 52.1 summarizes the drug classes. For specific drugs, other tables identify the AEDs administered, the dosage, pregnancy category, the type of seizure they are used to treat, and the therapeutic serum drug levels. The therapeutic serum drug level is very important because of the risk of drug toxicity.

QSEN Safety Alert

When administering AEDs requiring dosage calculation, two nurses should calculate the dosage, checking for accuracy.

Clinical Application 52-1

According to Andrew’s chart, he should receive carbamazepine (Tegretol) 50 mg four times per day. The elixir is 100 mg/5 mL. The boy weighs 56 pounds. How much carbamazepine does the nurse administer?

According to Andrew’s chart, he should receive carbamazepine (Tegretol) 50 mg four times per day. The elixir is 100 mg/5 mL. The boy weighs 56 pounds. How much carbamazepine does the nurse administer?

The physician has ordered sodium valproate (Depakene) 20 mg/kg/d for Andrew. The elixir is 250 mg/5 mL. How much sodium valproate does the nurse administer?

The physician has ordered sodium valproate (Depakene) 20 mg/kg/d for Andrew. The elixir is 250 mg/5 mL. How much sodium valproate does the nurse administer?

NCLEX Success

1. A male infant is admitted to the emergency department. His parents report that he had a seizure. The infant’s aural temperature is 104.3°F. What is the most likely cause of the seizure?

A. head injury

B. developmental delay

C. sepsis

D. fever

2. A woman is admitted to the labor and delivery unit with a blood pressure of 200/90 mm Hg. The admitting diagnosis is preeclampsia. The intravenous (IV) magnesium sulfate ordered for this patient prevents?

A. seizures

B. myocardial damage

C. tetany

D. hypothermia

3. A patient is having a seizure that lasts longer than 30 minutes. What type of generalized seizure is the patient experiencing?

A. tonic–clonic

B. absence seizure

C. atonic seizure

D. status epilepticus

4. A patient is admitted to the emergency department with repeated tonic–clonic seizures. Tonic–clonic seizures may be attributed to which of following drugs?

A. ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (Cipro)

B. cimetidine (Tagamet)

C. cocaine

D. morphine sulfate

Drugs Used to Treat Seizure Disorders

BARBITURATES

Phenobarbital (Luminal) is the prototype AED of the barbiturate class. Since its development in 1912, it has been used as an antiepileptic or sedative.

Phenobarbital (Luminal) is the prototype AED of the barbiturate class. Since its development in 1912, it has been used as an antiepileptic or sedative.

Pharmacokinetics

Phenobarbital, like all barbiturates, is absorbed rapidly through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, usually within 1 hour. The oral drug has an onset of action of 30 to 60 minutes and a duration of 10 to 16 hours. The IV form begins to act in 5 minutes and lasts for 4 to 6 hours. Phenobarbital has a half-life of 50 to 140 hours. The drug takes approximately 2 to 3 weeks to reach therapeutic serum levels and 3 weeks to reach a steady-state concentration. It is also lipid bound, which means that it crosses the placenta and is present in breast milk. Phenobarbital is metabolized in the liver and excreted by the renal system.

Action

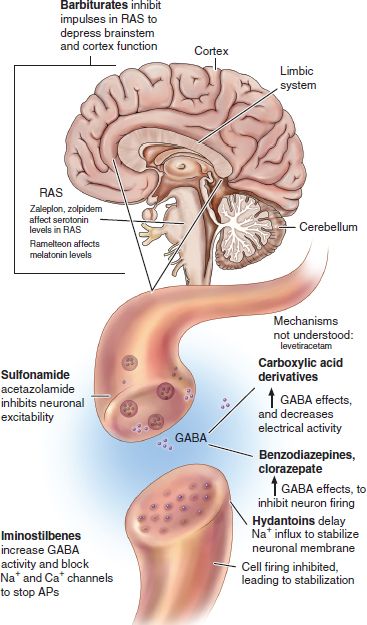

Phenobarbital depresses the CNS by inhibiting the conduction of impulses in the ascending reticular activating system, thus depressing the cerebral cortex and cerebellar function. Figure 52.1 indicates the site of action of barbiturates, along with other antiepileptic drugs.

Figure 52.1 Sites of action of antiepileptic drugs. AP, action potential; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; RAS, reticular activating system. (Adapted from Karch, A.M. (2013). Focus on nursing pharmacology. (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

Use

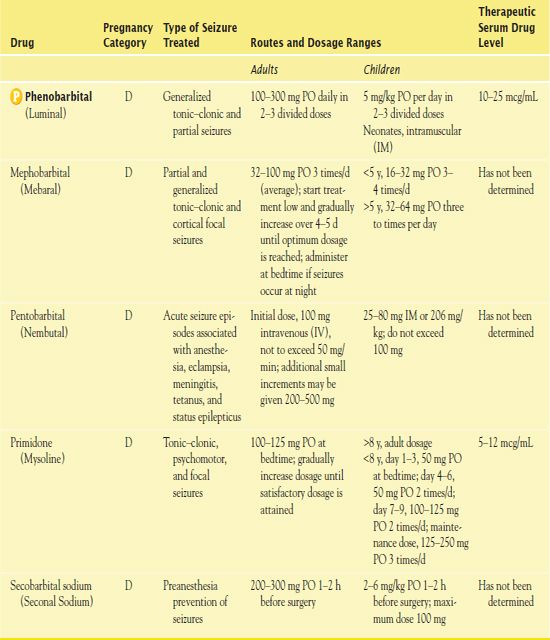

Prescribers order oral phenobarbital as a sedative and antiepileptic agent in the treatment of generalized tonic–clonic and partial seizures. Clinicians use the parenteral form to control acute seizures. Table 52.2 gives route and dosage information for phenobarbital and other barbiturates.

TABLE 52.2

TABLE 52.2

Use in Older Adults

Older adults may experience greater sedation, due to decreased absorption and altered renal excretion of phenobarbital, placing them at risk for injury. These patients may also be at risk for adverse drug reactions related to altered metabolism and excretion.

Use in Patients With Renal or Hepatic Impairment

Patients who have decreased creatinine clearance (CrCl) may not be able to excrete phenobarbital adequately. Patients with hepatic impairment require a lower dose to prevent adverse effects associated with the drug.

Use in Patients With Critical Illness

When administering phenobarbital parenterally, it is best to do so in a critical care unit. This allows for constant monitoring of drug effects and early resuscitation in the event of respiratory arrest.

Adverse Effects

As with all AEDs, CNS depression, possibly cognitive impairment with sedation, is the most common adverse effect. Other reported conditions include somnolence, agitation, confusion, vertigo, and nightmares. The most severe adverse effect is Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a hypersensitivity reaction. Respiratory problems may occur, particularly with parenteral phenobarbital. Sudden withdrawal of the medication places the patient at risk for status epilepticus. The FDA has issued a BLACK BOX WARNING ♦ for phenobarbital. Patients who take phenobarbital are at risk for suicidal ideation. It is important to monitor the patient for statements that indicate depression and suicide.

Contraindications

Contraindications to phenobarbital include a known hypersensitivity to barbiturates. Other contraindications include liver failure, nephritis, porphyria, respiratory depression, pregnancy, or addiction to barbiturates. Caution is necessary in acute or chronic pain, lactation, fever, hyperthyroidism, diabetes, decreased liver renal function, and pulmonary and cardiac disease.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Several drugs interact with phenobarbital, increasing its effects (Box 52.1). Opioid analgesics combined with phenobarbital result in enhanced CNS depression. When administered with phenobarbital, corticosteroids, doxycycline, estrogens, hormonal contraceptives, oral anticoagulants, and tricyclic antidepressants have an increased metabolism and a decreased effect. Oil of primrose increases the effects of phenobarbital.

BOX 52.1  Drug Interactions: Phenobarbital

Drug Interactions: Phenobarbital

Drugs That Increase the Effects of Phenobarbital

Alcohol, chloramphenicol, diazepam, monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Alcohol, chloramphenicol, diazepam, monoamine oxidase inhibitors

May increase central nervous system (CNS) and respiratory depression

Gabapentin, valproic acid

Gabapentin, valproic acid

Increase serum level

Mephobarbital, primidone

Mephobarbital, primidone

May increase serum level

Administering the Medication

Oral administration of phenobarbital may occur without regard to food. Parenteral administration may involve combining the medication with dextrose, lactated Ringer’s, or normal saline. However, if a precipitate forms, administration should not take place. Also, the drug is incompatible with acidic solutions, amphotericin B, chlorpromazine, diphenhydramine, insulin, and vancomycin. The nurse always injects IV phenobarbital into large veins at an infusion rate no faster than 60 mg/min. Inadvertent intra-arterial injection can cause spasm of the artery and gangrene. When administering the intramuscular (IM) drug, the nurse uses a large needle and injects into deep muscle.

Assessing for Therapeutic Effects

The ultimate goal of therapy with phenobarbital is to decrease seizure effects. The patient’s EEG reveals decreased brain waves consistent with seizure activity.

Assessing for Adverse Effects

The nurse assesses for increases in CNS activity consistent with paradoxical excitation, as noted most often in the elderly. It is essential to assess respiratory problems such as hypoventilation, apnea, respiratory depression, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and circulatory collapse, particularly in patients receiving parenteral phenobarbital. In addition, it is necessary to

• Assess for bradycardia, hypotension, and syncope

• Assess the serum drug level for signs of toxicity or inadequate seizure treatment

• Assess for changes in the integumentary system indicative of the onset of Stevens-Johnson syndrome

Patient Teaching

Box 52.2 identifies patient teaching guidelines for phenobarbital.

BOX 52.2  Patient Teaching Guidelines for Phenobarbital

Patient Teaching Guidelines for Phenobarbital

Understand that this drug is administered long term for the treatment of seizure activity.

Understand that this drug is administered long term for the treatment of seizure activity.

Take the medication as prescribed, and do not stop the medication abruptly.

Take the medication as prescribed, and do not stop the medication abruptly.

Have regular tests to determine serum levels of the drug.

Have regular tests to determine serum levels of the drug.

Change positions slowly. This drug may cause drowsiness or syncope.

Change positions slowly. This drug may cause drowsiness or syncope.

Do not drive or operate machinery with central nervous system (CNS) depression.

Do not drive or operate machinery with central nervous system (CNS) depression.

If you are of childbearing age, use two forms of contraception.

If you are of childbearing age, use two forms of contraception.

Notify your prescriber about the development of rashes or skin eruptions.

Notify your prescriber about the development of rashes or skin eruptions.

Wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace stating that you have a seizure disorder and naming the medications you take.

Wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace stating that you have a seizure disorder and naming the medications you take.

BENZODIAZEPINES

Drugs belonging to this class have a broad range of uses; they may act as antidepressants, antiepileptics, or skeletal muscle relaxants. The benzodiazepines potentiate the effects of GABA by increasing the attraction to the receptor sites. The prototype of this class is  diazepam (Valium). See Figure 52.1 for the increased effects of GABA by benzodiazepines.

diazepam (Valium). See Figure 52.1 for the increased effects of GABA by benzodiazepines.

Pharmacokinetics

This varies with the preparation of diazepam. For the IV drug, the onset of action is 1 to 5 minutes, with a peak of 30 minutes and a duration of 15 to 60 minutes. For the oral drug, the onset of action of 30 to 60 minutes, with a peak of 1 to 2 hours and duration of 3 hours. For the IM drug, the onset of action is generally within 15 to 30 minutes, with a peak of 30 to 45 minutes and a duration of 3 hours. For the rectal drug, the onset is rapid, with a peak of 1.5 hours and a duration of 3 hours. Its half-life, which is longer in newborns and the elderly, is 20 to 80 hours.

Diazepam crosses the placenta and enters the breast milk. It is metabolized by the liver and excreted by the kidneys.

Action

The exact mechanism of action of diazepam is unknown. However, authorities believe that the drug acts primarily on the limbic system and reticular formation to produce skeletal muscle relaxation. It potentiates the effect of GABA by increasing the attraction of the medication to the receptor sites.

Use

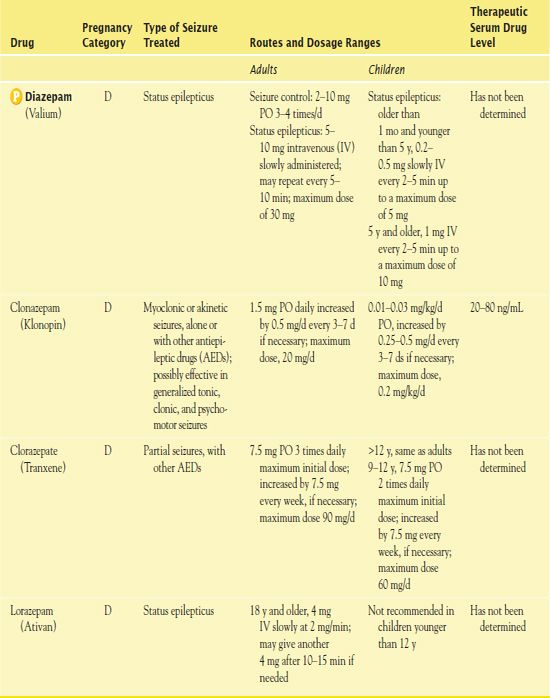

IV diazepam is an adjunctive skeletal muscle relaxant administered for the treatment of severe recurrent convulsive seizures and status epilepticus. Oral diazepam is an adjunctive agent used for seizure disorders. Clinicians also order benzodiazepines such as diazepam for treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a mixed seizure disorder that presents at approximately 2 years of age. Table 52.3 gives route and dosage information for diazepam and other benzodiazepines.

TABLE 52.3

TABLE 52.3

Use in Children

IV diazepam is recommended for use in children age 1 month or older. Newborns require a lower dose. Oral diazepam is recommended for children older than 6 months of age. Rectal administration is not recommended in children younger than 2 years of age.

Use in Older Adults

It is necessary to reduce the dosage of diazepam administered to older adults because the drug has an extended half-life in this population.

Use in Patients With Renal or Hepatic Impairment

Diazepam is excreted by the kidneys after being metabolized in the liver. Thus, patients with renal or hepatic impairment should take reduced dosages of diazepam.

Use in Patients With Critical Illness

Patients with critical illness or those in debilitated states should take reduce dosages of diazepam. During IV administration, patients should receive oxygen.

Adverse Effects

CNS adverse effects of diazepam include depression, disorientation, restlessness, and confusion. In the first 2 weeks of treatment, paradoxical excitatory reactions may occur. The most serious cardiovascular adverse effect is cardiovascular collapse with bradycardia and hypotension. Also, potentially life-threatening tachycardia may occur. Other reported problems include constipation, diarrhea, incontinence, urinary retention, and changes in libido.

Contraindications

Patients with known hypersensitivity to benzodiazepines should not receive diazepam. Contraindications also include acute narrow-angle glaucoma, shock, coma, acute alcohol intoxication, and pregnancy.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Many medications and herbs interact with diazepam, decreasing or increasing its effects (Boxes 52.3 and 52.4).

BOX 52.3  Drug Interactions: Diazepam

Drug Interactions: Diazepam

Drugs That Increases the Effect of Diazepam

Alcohol, omeprazole

Alcohol, omeprazole

Increase central nervous system (CNS) depression

Cimetidine, disulfiram, and hormonal contraceptives

Cimetidine, disulfiram, and hormonal contraceptives

Increase pharmacological effects

Drugs That Decrease the Effects Diazepam

Theophylline, ranitidine

Theophylline, ranitidine

Decrease pharmacological effects

BOX 52.4  Herb and Dietary Interactions: Diazepam

Herb and Dietary Interactions: Diazepam

Herbs and Foods That Increase the Effect of Diazepam

Kava

Kava

Valerian

Valerian

Grapefruit juice

Grapefruit juice

Administering the Medication

When preparing diazepam, the nurse does not mix the drug in plastic bags or tubing or combine it with other solutions. During administration, it is important to monitor pulse, blood pressure, and respiration. During parenteral administration, it is necessary to administer oxygen as well as to put the patient on bedrest for 3 hours. The nurse injects the IV form of the drug slowly into a large vein at 1 mL/min—over at least 3 minutes in children—never intra-arterially or into small veins. Intra-arterial administration results in arterial spasm.

Assessing for Therapeutic Effects

When administering diazepam for a seizure disorder, the goal of therapy is to control seizure activity. When administering drug for status epilepticus, the goal is to eliminate the seizure activity.

Assessing for Adverse Effects

The nurse assesses for changes in cardiovascular status that could indicate hypotension, bradycardia, or tachycardia. He or she closely monitors the CNS response. In addition, the nurse assesses for alterations in elimination patterns.

Patient Teaching

BOX 52.5 identifies patient teaching guidelines for diazepam.

BOX 52.5  Patient Teaching Guidelines for Diazepam

Patient Teaching Guidelines for Diazepam

Take the medication as prescribed and do not skip doses or stop therapy.

Take the medication as prescribed and do not skip doses or stop therapy.

Do not use alcohol or smoke. Alcohol is more potent when combined with diazepam. Smoking may constrict blood vessels, resulting in reduced elimination of the drug.

Do not use alcohol or smoke. Alcohol is more potent when combined with diazepam. Smoking may constrict blood vessels, resulting in reduced elimination of the drug.

Obtain instructions about the administration of rectal diazepam.

Obtain instructions about the administration of rectal diazepam.

Use two types of contraceptives if you are a woman of childbearing age and are sexually active.

Use two types of contraceptives if you are a woman of childbearing age and are sexually active.

Ask your prescriber about safety and central nervous system (CNS) depression. Protect yourself from falls. Do not drive or operate machinery if you have CNS depression.

Ask your prescriber about safety and central nervous system (CNS) depression. Protect yourself from falls. Do not drive or operate machinery if you have CNS depression.

Wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace stating that you have a seizure disorder and naming the medications you take.

Wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace stating that you have a seizure disorder and naming the medications you take.

Clinical Application 52-2

During a hospitalization, Andrew has an episode of status epilepticus. His neurologist orders diazepam (Valium) 1 mg IV every 2 to 5 minutes, with a maximum dosage of 10 mg. How does the nurse administer the medication?

During a hospitalization, Andrew has an episode of status epilepticus. His neurologist orders diazepam (Valium) 1 mg IV every 2 to 5 minutes, with a maximum dosage of 10 mg. How does the nurse administer the medication?

What assessments and interventions are necessary to implement before, during, and after the administration of diazepam?

What assessments and interventions are necessary to implement before, during, and after the administration of diazepam?

NCLEX Success

5. Which of the following medications is administered for status epilepticus?

A. phenytoin (Dilantin)

B. diazepam (Valium)

C. levetiracetam (Keppra)

D. mephobarbital (Mebaral)

6. A patient is taking phenobarbital (Luminal) for a seizure disorder. Which of the following statements indicates that the patient should be seen by a health care provider immediately?

A. “I have a rash that started on my trunk, and now it is on my arms and legs.”

B. “I rest if I feel tired.”

C. “I take my medication routinely and do not skip doses.”

D. “I have my blood levels checked if my breathing decreases.”

7. A patient stops taking clonazepam (Klonopin). What adverse effect will occur?

A. status epilepticus

B. bone marrow depression

C. cerebral edema

D. lethargy

GAMMA-AMINOBUTYRIC ACID STRUCTURAL ANALOGS

In 1993, the FDA approved  gabapentin (Neurontin) for treatment of partial seizures. In May of 2002, the FDA approved it for treatment of postherpetic neuralgia pain.

gabapentin (Neurontin) for treatment of partial seizures. In May of 2002, the FDA approved it for treatment of postherpetic neuralgia pain.

Pharmacokinetics and Action

Gabapentin reaches its peak in 1 hour. Metabolism occurs in the liver and elimination takes place in the urine. The drug crosses the placenta and may enter the breast milk.

Its antiepileptic action is related to its ability to inhibit post-synaptic responses and block post-tetanic potentiation.

Use

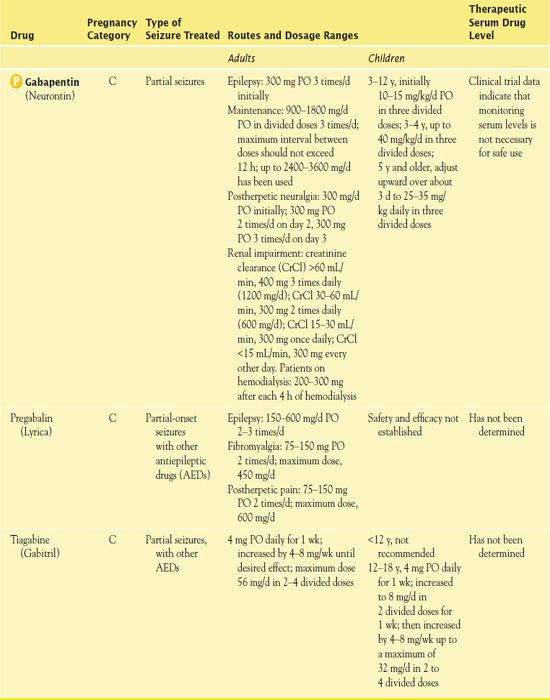

Prescribers order gabapentin as an adjunctive treatment for partial seizures. Table 52.4 gives route and dosage information for gabapentin and other GABA structural analogs.

TABLE 52.4

TABLE 52.4

AED, antiepileptic drug.

Use in Patients With Renal Impairment

Patients with impaired renal function may require dosage adjustment depending on their CrCl.

Use in Patients With Hepatic Impairment

Patients with impaired liver function require monitoring for elevated liver enzymes.

Adverse Effects

The most common adverse effects of gabapentin are associated with CNS depression and include dizziness, somnolence, insomnia, and ataxia. Other reported adverse effects are pruritus, dry mouth, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, and suicidal ideation.

Contraindications

Contraindications to gabapentin include a known hypersensitivity to the medication.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Antacids do not affect the serum level but they decrease absorption of gabapentin when administered at the same time. The herb Ginkgo biloba decreases the effect of the drug.

Administering the Medication

The nurse ensures that gabapentin is taken orally. People may take the drug with food to prevent GI upset.

Assessing for Therapeutic and Adverse Effects

The nurses assesses for the absence of partial seizures, the most important therapeutic effect.

It is also necessary to assess changes in mood and personality in patients receiving gabapentin, as with all antiepileptic medications, because suicidal ideation is the result of CNS depression. The nurse assesses for CNS depression that could affect patient safety.

Patient Teaching

Box 52.6 identifies patient teaching guidelines for gabapentin.

BOX 52.6  Patient Teaching Guidelines for Gabapentin

Patient Teaching Guidelines for Gabapentin

Take the medication as prescribed and do not stop taking it abruptly.

Take the medication as prescribed and do not stop taking it abruptly.

Take the medication with food to decrease gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort.

Take the medication with food to decrease gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort.

Do not cut, crush, or chew extended-release capsules. If swallowing is difficult, sprinkle the contents of the capsule over soft food.

Do not cut, crush, or chew extended-release capsules. If swallowing is difficult, sprinkle the contents of the capsule over soft food.

Notify your prescriber if seizure activity occurs.

Notify your prescriber if seizure activity occurs.

You may experience nausea, vomiting, insomnia, fatigue, and confusion.

You may experience nausea, vomiting, insomnia, fatigue, and confusion.

Do not drive or operate machinery with central nervous system (CNS) depression.

Do not drive or operate machinery with central nervous system (CNS) depression.

Report severe nausea and vomiting, changes in stool or urine color, diarrhea, or changes in neurologic function to the prescriber.

Report severe nausea and vomiting, changes in stool or urine color, diarrhea, or changes in neurologic function to the prescriber.

HYDANTOINS

The prototype antiepileptic of the hydantoin class is  phenytoin (Dilantin). The oldest and most widely used AED, it is often the initial drug of choice, especially in adults. In addition to using it to treat seizure disorders, prescribers sometimes order it for cardiac dysrhythmias.

phenytoin (Dilantin). The oldest and most widely used AED, it is often the initial drug of choice, especially in adults. In addition to using it to treat seizure disorders, prescribers sometimes order it for cardiac dysrhythmias.

Pharmacokinetics

Phenytoin is highly bound (90%) to plasma proteins, and only the free drug (the fraction not bound to plasma albumin) is therapeutically active. The oral preparation, absorbed by the GI tract, has a slow onset of action, with a peak of 2 to 12 hours and a duration of 6 to 12 hours. The IV preparation has an onset of action of 1 to 2 hours with a rapid peak and a duration of 12 to 24 hours. The drug is metabolized by the liver and excreted in the urine.

Action

Phenytoin stabilizes the neuronal membrane by delaying the influx of sodium ions into the neurons and preventing the excitability caused by excessive stimulation. See Figure 52.1 for the site of action of hydantoins.

Use

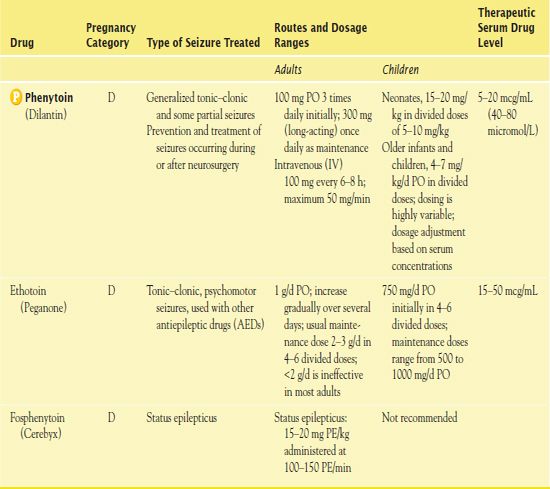

Clinicians use phenytoin to control tonic–clonic seizures, psychomotor seizures, and nonepileptic seizures. They also use it to prevent seizure activity in patients during and following neurosurgery and brain injury. Table 52.5 gives route and dosage information for phenytoin and the other hydantoins.

TABLE 52.5

TABLE 52.5

PE, phenytoin equivalent.

Phenytoin is available in several forms: a capsule (generic, Dilantin), chewable tablet, oral suspension, and injectable solution. Patients should not switch between generic and trade name formulations because of differences in absorption and bioavailability. If a patient becomes stable on a generic drug and then switches to Dilantin, there is a risk of higher serum phenytoin levels and toxicity. If a patient becomes stable on Dilantin and then switches to a generic drug, there is a risk of lower serum phenytoin levels, loss of therapeutic effectiveness, and seizures. (There may also be differences in bioavailability among generic formulations manufactured by different companies.)

Use in Children

When used for status epilepticus, the IV phenytoin dose is determined according to the weight of the child. The recommended dosage is 10 to 15 mg/kg.

Use in Older Adults

It is necessary to administer phenytoin cautiously to older adults. Elderly patients may have altered albumin levels, decreasing the affinity of phenytoin for albumin and causing displacement of the drug.

Use in Patients With Renal Impairment

Renal impairment or failure also causes displacement of the drug, placing the patient at risk for toxicity.

Use in Patients With Hepatic Impairment

Hepatic impairment results in altered albumin levels, decreasing the affinity of phenytoin for albumin and causing displacement of the drug.

Use in Patients With Critical Illness

The IV administration of phenytoin can result in cardiovascular collapse. It is important to assess blood pressure, pulse, and respirations. Monitoring the patient’s cardiovascular status is necessary with the use of telemetry.

Adverse Effects

The most common adverse effects of phenytoin affect the CNS (e.g., ataxia, drowsiness, lethargy) and GI tract (e.g., nausea, vomiting). Gingival hyperplasia, an overgrowth of gum tissue, is also common, especially in children. Long-term use may lead to an increased risk of osteoporosis because of its effect on vitamin D metabolism. Serious reactions are uncommon but may include allergic reactions, hepatitis, nephritis, bone marrow depression, and mental confusion.

Contraindications

Contraindications to phenytoin include a known hypersensitivity to the hydantoins. Other conditions that require caution are seizures related to hypoglycemia, sinus bradycardia, heart block, and Stokes-Adams syndrome. In patients exhibiting seizures related to hypoglycemia, the primary treatment involves interventions to increase blood glucose (not the use of AEDs). Given the sedative effects associated with phenytoin, the patient is at risk for decreased heart rate; thus, frequent assessment of cardiac output is required if phenytoin is administered to these patients. Caution is also required when administering phenytoin to pregnant women. The risk of birth defects is a significant adverse effect.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Several medications interact with phenytoin, increasing or decreasing its effects (Box 52.7). The effectiveness of corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, and nisoldipine is reduced when combined with phenytoin. Absorption of folic acid, calcium, and vitamin D is decreased with the administration of phenytoin. The herb Ginkgo biloba decreases the effect of the drug.

BOX 52.7  Drug Interactions: Phenytoin*

Drug Interactions: Phenytoin*

Drugs That Increase the Effects of Phenytoin

Alcohol, amiodarone, chloramphenicol, omeprazole, ticlopidine

Alcohol, amiodarone, chloramphenicol, omeprazole, ticlopidine

Increase phenytoin levels

Drugs That Decrease the Effects of Phenytoin

Enteral feedings

Enteral feedings

Decrease phenytoin absorption

*Complex interactions and effects may occur when phenytoin and valproic acid are taken together. Phenytoin toxicity may result with apparently normal serum phenytoin levels.

Administering the Medication

The injectable solution is highly irritating to tissues. Therefore, when giving the drug intravenously, it is necessary to use special techniques.

Assessing for Therapeutic and Adverse Effects

The nurse assess for the absence of tonic–clonic and psychomotor seizures.

The nurse assesses for the presence of a rash or skin eruption indicative of a hypersensitivity reaction; the presence of a skin eruption could be indicative of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. In addition, the nurse assesses for cardiovascular collapse with IV administration.

Patient Teaching

Box 52.8 identifies patient teaching guidelines for phenytoin.

BOX 52.8  Patient Teaching Guidelines for Phenytoin

Patient Teaching Guidelines for Phenytoin

Take the drug as prescribed and do not stop taking it abruptly.

Take the drug as prescribed and do not stop taking it abruptly.

Take the medication with food to prevent gastric upset.

Take the medication with food to prevent gastric upset.

Have serum drug levels checked as ordered by your prescriber.

Have serum drug levels checked as ordered by your prescriber.

Maintain good oral hygiene (regular brushing and flossing) to prevent gum disease.

Maintain good oral hygiene (regular brushing and flossing) to prevent gum disease.

Have regular dental check-ups.

Have regular dental check-ups.

Use contraception if you are of childbearing age and are sexually active.

Use contraception if you are of childbearing age and are sexually active.

Wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace, stating that you have a seizure disorder and naming the medications you take.

Wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace, stating that you have a seizure disorder and naming the medications you take.

IMINOSTILBENES

The AEDs classified as the iminostilbenes include the prototype  carbamazepine (Tegretol).

carbamazepine (Tegretol).

Pharmacokinetics

Carbamazepine is administered orally and absorbed by the GI tract. The onset of action is slow in both the oral and oral extended-release preparations. The regular oral preparation peaks in 4 to 5 hours, whereas the extended-release preparation peaks in 3 to 12 hours. The half-life of the drug is 12 to 17 hours. It is metabolized by the liver and excreted in the feces and urine. Carbamazepine crosses the placenta and enters breast milk.

Action

The mechanism of action of carbamazepine is not understood, but its antiepileptic activity may be related to inhibition of polysynaptic responses that block post-tetanic potentiation. Like the tricyclic antidepressants, the drug affects sodium channels within the cortical neurons. It has the ability to decrease action potential of the cell by inhibiting the influx of sodium into the cell. See Figure 52.1 for the site of action of the iminostilbenes.

Use

Clinicians use carbamazepine to prevent partial seizures with complex symptoms, as in patients with psychomotor and temporal lobe epilepsy. Prescribers order the drug for generalized tonic–clonic and mixed seizures, either partial or generalized. Patients who have uncontrolled seizures or CNS depression on other AEDs use it commonly. Table 52.6 presents route and dosage information for carbamazepine and another iminostilbene.

TABLE 52.6

TABLE 52.6Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree