Describe the main elements of peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Discuss antacids in terms of the prototype, indications and contraindications for use, routes of administration, and major adverse effects.

Discuss antacids in terms of the prototype, indications and contraindications for use, routes of administration, and major adverse effects.

Describe histamine2 receptor antagonists in terms of the prototype, indications and contraindications for use, routes of administration, and major adverse effects.

Describe histamine2 receptor antagonists in terms of the prototype, indications and contraindications for use, routes of administration, and major adverse effects.

Discuss proton pump inhibitors in terms of the prototype, indications and contraindications for use, routes of administration, and major adverse effects.

Discuss proton pump inhibitors in terms of the prototype, indications and contraindications for use, routes of administration, and major adverse effects.

Identify the adjuvant medications used to treat peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Identify the adjuvant medications used to treat peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Understand how to use the nursing process in the care of patients receiving antacids, proton pump inhibitors, and histamine2 receptor antagonists.

Understand how to use the nursing process in the care of patients receiving antacids, proton pump inhibitors, and histamine2 receptor antagonists.

Clinical Application Case Study

Kathleen Daniels, a 54-year-old woman, has chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. She takes omeprazole (Prilosec) 20 mg orally daily, as prescribed. She also takes two over-the-counter medications: famotidine (Pepcid) 10 mg twice a day as needed, to control her heartburn, and a combination antacid (Mylanta) 5 mL per dose.

KEY TERMS

Achlorhydria: low or absent production of gastric acid in the stomach

Cardia: the part of the stomach that attaches to the esophagus

Esophagitis: inflammation of the esophagus

Gastritis: acute or chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa

Helicobacter pylori: gram-negative bacterium found in the gastric mucosa of most patients with chronic gastritis.

Hydrogen, potassium adenosine triphosphatase: enzyme system that catalyzes the production of gastric acid and acts as a gastric acid pump to move gastric acid from parietal cells in the mucosal lining of the stomach into the stomach lumen

Pepsin: proteolytic enzyme that helps digests protein foods

Pyrosis: heartburn

Stress ulcers: gastric mucosal lesions that develop in patients who are critically ill from trauma, shock, hemorrhage, sepsis, burns, acute respiratory distress syndrome, major surgical procedures, or other severe illnesses.

Introduction

Drugs to prevent or treat peptic ulcer and acid reflux disorders consist of several groups of drugs, most of which alter gastric acid and its effects on the mucosa of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. To aid understanding of drug effects, this chapter presents an overview of both peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) before providing details about specific drugs. Box 35.1 gives further descriptions of selected upper GI disorders.

BOX 35.1 Selected Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders

Gastritis

Gastritis, a common disorder, is an acute or chronic inflammatory reaction of gastric mucosa. Patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers usually also have gastritis. Acute gastritis (also called gastropathy) usually results from irritation of the gastric mucosa by such substances as alcohol, aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and others. Chronic gastritis is usually caused by Helicobacter pylori infection and it persists unless the infection is treated effectively. H. pylori organisms may cause gastritis and ulceration by producing enzymes (e.g., urease, others) that break down mucosa; they also alter secretion of gastric acid.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Gastropathy

NSAID gastropathy indicates damage to gastroduodenal mucosa by aspirin and other NSAIDs. The damage may range from minor superficial erosions to ulceration and bleeding. NSAID gastropathy is one of the most common causes of gastric ulcers, and it may cause duodenal ulcers as well. Many people take NSAIDs daily for pain, arthritis, and other conditions. Chronic ingestion of NSAIDs causes local irritation of gastroduodenal mucosa, inhibits the synthesis of prostaglandins (which normally protect gastric mucosa by inhibiting acid secretion, stimulating secretion of bicarbonate and mucus, and maintaining mucosal blood flow), and increases the synthesis of leukotrienes and possibly other inflammatory substances that may contribute to mucosal injury.

Stress Ulcers

Stress ulcers indicate gastric mucosal lesions that develop in patients who are critically ill from trauma, shock, hemorrhage, sepsis, burns, acute respiratory distress syndrome, major surgical procedures, or other severe illnesses. The lesions may be single or multiple ulcers or erosions. Stress ulcers are usually manifested by painless upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. The frequency of occurrence has decreased, possibly because of improved management of sepsis, hypovolemia, and other disorders associated with critical illness and the prophylactic use of antiulcer drags. However, there is concern about inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis.

Although the exact mechanisms of stress ulcer formation are unknown, several factors are thought to play a role, including mucosal ischemia, reflux of bile salts into the stomach, reduced GI-tract motility, and systemic acidosis. Acidosis increases severity of lesions, and correction of acidosis decreases their formation. In addition, lesions do not form if the pH of gastric fluids is kept at about 3.5 or above and lesions apparently form only when mucosal blood flow is diminished.

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a rare condition characterized by excessive secretion of gastric acid and a high incidence of ulcers. It is caused by gastrin-secreting tumors in the pancreas, stomach, or duodenum. Approximately two thirds of the gastrinomas are malignant. Symptoms are those of peptic ulcer disease, and diagnosis is based on high levels of serum gastrin and gastric acid. Treatment may involve long-term use of a proton pump inhibitor to diminish gastric acid or surgical excision.

Overview of Peptic Ulcer Disease and I Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic ulcer disease is characterized by ulcer formation in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum—areas of the GI mucosa that are exposed to gastric acid and pepsin. Gastric and duodenal ulcers are more common than esophageal ulcers. Infection with Helicobacter pylori and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) account for most cases of peptic ulcer disease. H. pylori is a gram-negative bacterium found in the gastric mucosa of most patients with chronic gastritis (inflammation of the gastric mucosa), about 75% of patients with gastric ulcers, and more than 90% of patients with duodenal ulcers. The World Health Organization reports that H. pylori is also present in 50% of all new cases of gastric cancer cases. This bacterium is spread mainly by the fecal-oral route. However, iatrogenic spread by contaminated endoscopes, biopsy forceps, and nasogastric tubes has also occurred.

In addition, stress (e.g., major trauma, severe medical illness) can precipitate ulcer formation. Gastric ulcers are more likely to occur in older adults, especially in the sixth and seventh decades, and to be chronic in nature. Duodenal ulcers are strongly associated with H. pylori infection and NSAID ingestion, may occur at any age, occur about equally in men and women, are often manifested by abdominal pain, and are usually chronic in nature. They are also associated with cigarette smoking. Compared with nonsmokers, smokers are more likely to develop duodenal ulcers, their ulcers heal more slowly with treatment, and the ulcers recur more rapidly.

Peptic ulcers seem to result from an imbalance between cell-destructive and cell-protective effects (i.e., presence of increased destructive mechanisms or presence of decreased protective mechanisms). Cell-destructive effects include those of gastric acid (hydrochloric acid), pepsin, H. pylori infection, and NSAID ingestion. Gastric acid, a strong acid that can digest the stomach wall, is secreted by parietal cells in the mucosa of the stomach antrum, near the pylorus. The parietal cells contain receptors for acetylcholine, gastrin, and histamine, substances that stimulate gastric acid production. Acetylcholine is released by vagus nerve endings in response to stimuli, such as thinking about or ingesting food. Gastrin is a hormone released by cells in the stomach and duodenum in response to food ingestion and stretching of the stomach wall. It is secreted into the bloodstream and eventually circulated to the parietal cells. Histamine is released from cells in the gastric mucosa and diffuses into nearby parietal cells. The enzyme system hydrogen, potassium adenosine triphosphatase (H+, K+-ATPase) catalyzes the production of gastric acid and acts as a gastric acid (proton) pump to move gastric acid from parietal cells in the mucosal lining of the stomach into the stomach lumen.

Pepsin, a proteolytic enzyme, helps digest protein foods and also can digest the stomach wall. Pepsin is derived from a precursor called pepsinogen, which is secreted by chief cells in the gastric mucosa. Pepsinogen is converted to pepsin only in a highly acidic environment (i.e., when the pH of gastric juices is 3 or less).

After H. pylori moves into the body, the bacterium colonizes the mucus-secreting epithelial cells of the stomach mucosa and is thought to produce gastritis and ulceration by impairing mucosal function. Eradication of the microorganism accelerates ulcer healing and significantly decreases the rate of ulcer recurrence.

Cell-protective effects (e.g., secretion of mucus and bicarbonate, dilution of gastric acid by food and secretions, prevention of diffusion of hydrochloric acid from the stomach lumen back into the gastric mucosal lining, the presence of prostaglandin E, alkalinization of gastric secretions by pancreatic juices and bile, perhaps other mechanisms) normally prevent autodigestion of stomach and duodenal tissues and ulcer formation.

A gastric or duodenal ulcer may penetrate only the mucosal surface or it may extend into the smooth muscle layers. When superficial lesions heal, no defects remain. When smooth muscle heals, however, scar tissue remains and the mucosa that regenerates to cover the scarred muscle tissue may be defective. These defects contribute to repeated episodes of ulceration.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

GERD, the most common disorder of the esophagus, is a chronic digestive disease that occurs when stomach acid or, occasionally, bile refluxes into the esophagus. The backwash of acid irritates the lining of the esophagus. The main cause of GERD is thought to be an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Normally, the LES is contracted or closed and prevents the reflux of gastric contents. It opens or relaxes on swallowing to allow passage of food or fluid, then contracts again. Several circumstances contribute to impaired contraction of the LES and the resulting reflux, including foods (e.g., fats, chocolate), fluids (e.g., alcohol, caffeinated beverages), medications (e.g., beta adrenergics, calcium channel blockers, nitrates), gastric distention, cigarette smoking, and recumbent posture. GERD occurs in men, women, and children but is especially common during pregnancy and after 40 years of age.

The part of the stomach that connects to the esophagus is called the cardia. In healthy patients, the esophagus enters the stomach at an angle, forming a valve that prevents gastric contents from traveling back into the esophagus. In patients with GERD, pathophysiologic effects and symptoms result from failure of the cardia. Additionally, H. pylori infection is present in nearly half of all patients with GERD.

GERD is characterized by regurgitation of duodenal bile, enzymes, and stomach acid into the esophagus and exposure of esophageal mucosa to gastric acid and pepsin. The same amount of acid-pepsin exposure may lead to different amounts of mucosal damage, possibly related to individual variations in esophageal mucosal resistance.

Clinical Manifestations

Peptic Ulcer Disease

The clinical manifestations of a gastric ulcer are almost opposite to the clinical manifestations of duodenal ulcers; the main differences are the timing and severity of the pain. Gastric ulcers generally cause a dull aching pain, often right after eating. The intake of food does not relieve pain as is the case with a duodenal ulcer. The patient may experience bloating, indigestion, heartburn, or nausea. Gastric ulcers are often manifested by painless bleeding and take longer to heal than duodenal ulcers. Duodenal ulcers cause heartburn, bloating, severe stomach pain, and a burning sensation at the back of the throat. The symptoms may be worse when the stomach is empty and may flare at night. Typically the symptoms disappear and then return for a period of time.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Pyrosis (heartburn), which increases with a recumbent position or bending over, is the main symptom of GERD. Effortless regurgitation of acidic fluid into the mouth, especially after a meal and at night, is often indicative. Important protective mechanisms for the esophagus, including gravity, swallowing, and saliva, are effective only when people are upright. At night during sleep in a recumbent position, the effect of gravity is negated, swallowing ceases, and the secretion of saliva is decreased. Consequently, reflux that occurs at night probably results in acid staying in the esophagus longer and causing greater damage. Many people experience both pyrosis and acid reflux from time to time. When they occur regularly, they may be signs of GERD. In addition, there may also be mild to severe esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus) or esophageal ulceration. Pain on swallowing usually means erosive or ulcerative esophagitis.

Drug Therapy

Drugs used in the treatment of acid-peptic disorders promote healing of lesions and prevent recurrence of lesions by decreasing cell-destructive effects or increasing cell-protective effects. Several types of drugs are used, alone and in various combinations. Antacids neutralize gastric acid and decrease pepsin production, antimicrobials and bismuth can eliminate H. pylori infection, histamine2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) decrease gastric acid secretion, sucralfate provides a barrier between mucosal erosions or ulcers and gastric secretions, and misoprostol restores prostaglandin activity. The following sections describe the types of drugs and individual agents. Table 35.1 lists the drugs used for peptic ulcer disease and GERD.

Available drugs are safe and effective.

QSEN Safety Alert

Taking herbal supplements may delay drug treatment and have harmful consequences; therefore, it is important that nurses and other health care providers do not encourage the use of herbs for any acid-peptic disorder.

Antacids

People commonly take over-the-counter (OTC) antacids to offset the effects of GI acids. These drugs differ in their ability to neutralize gastric acid (50-80 mEq of acid is produced hourly), in onset of action, and in adverse effects. Commonly used antacids are mixtures of aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide, as well as other ingredients. The aluminum hydroxide-magnesium hydroxide-simethicone mixture  Mylanta is the prototype. (In this discussion, the trade name of the drug is used to refer to this antacid.)

Mylanta is the prototype. (In this discussion, the trade name of the drug is used to refer to this antacid.)

Some antacids contain calcium compounds. It is important to note that calcium compounds may cause hypercalcemia and hypersecretion of gastric acid (“acid rebound”) due to stimulation of gastrin release, if large doses are used. Consequently, calcium compounds are rarely used in peptic ulcer disease.

Pharmacokinetics and Action

Absorption of Mylanta from the GI tract is minimal. Excretion is in the urine.

As an alkaline substance that neutralizes acids, Mylanta reacts with hydrochloric acid in the stomach to produce neutral, less acidic, or poorly absorbed salts and to raise the pH of gastric secretions. Raising the pH to approximately 3.5 neutralizes more than 90% of gastric acid and inhibits conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin. The antacid has an onset of action of 20 to 60 minutes. In general, aluminum compounds have a low neutralizing capacity (i.e., relatively large doses are required) and a slow onset of action. Magnesium-based antacids have a high neutralizing capacity and a rapid onset of action.

Simethicone, an antiflatulent drug, does not affect gastric acidity. It reportedly decreases gas bubbles, thereby reducing GI distention and abdominal discomfort.

Use

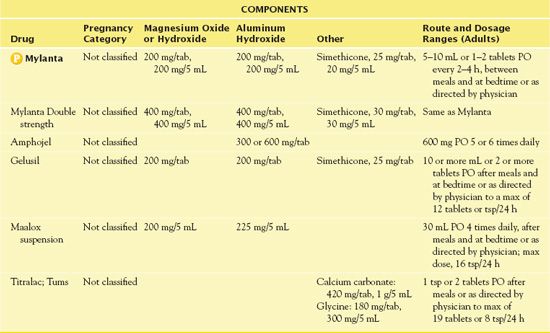

Antacids act primarily in the stomach, and people take them to prevent or treat peptic ulcer disease, GERD, esophagitis, heartburn, gastritis, GI bleeding, and stress ulcers. When pain relief is the goal of treatment, taking them on an as-needed basis is usually sufficient. However, it is important not to take them in high doses or for prolonged periods because of potential adverse effects. Table 35.2 gives route and dosage information for various antacids.

TABLE 35.2

TABLE 35.2

Use in Children

Ambulatory children may take Mylanta and the other antacids in doses of 5 to 15 mL every 3 to 6 hours, or after meals, and at bedtime. For prevention of GI bleeding in critically ill children, infants may receive 2 to 5 mL and children may receive 5 to 15 mL every 1 to 2 hours.

Use in Older Adults

Older adults may use all of the antiulcer, anti-heartburn drugs. With Mylanta and the other antacids, smaller doses may be effective because older adults usually secrete less gastric acid than younger adults. Also, with decreased renal function, older adults are more likely to have adverse effects, Many physicians recommend calcium carbonate antacids (e.g., Tums) as a calcium supplement in older women to prevent or treat osteoporosis.

Use in Patients With Renal Impairment

Patients with renal failure or with impaired renal function (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min) should not take magnesium-based antacids such as Mylanta because 5% to 10% of the magnesium may be absorbed and accumulate to cause hypermagnesemia. Patients with chronic renal failure and hyperphosphatemia may take aluminum-based antacids to decrease absorption of phosphates in food. (Aluminum binds with phosphate in the GI tract, preventing phosphate absorption and hyperphosphatemia that commonly occurs in renal failure.) However, aluminum may accumulate in patients with renal failure, leading to encephalopathy, erythropoietin-resistant anemia, and osteomalacia.

Antacids containing calcium carbonate are currently recommended for the purpose of controlling phosphate levels in patients with end-stage renal failure. Antacids with calcium carbonate can cause alkalosis and raise urine pH, and chronic use may cause renal stones and hypercalcemia.

Use in Patients With Critical Illness

To prevent stress ulcers (gastric mucosal lesions that occur due to physiologic stress) in critically ill patients and to treat acute GI bleeding, nearly continuous neutralization of gastric acid is desirable. Dose and frequency of administration must be sufficient to neutralize the gastric acid: a continuous intragastric drip through a nasogastric tube is effective. For patients with a nasogastric tube in place, antacid dosage may be titrated by aspirating stomach contents, determining pH and then basing the dose on the pH, (Most gastric acid is neutralized and most pepsin activity is eliminated at a pH above 3.5.)

Use in Patients Receiving Home Care

People commonly take all of the antiulcer, anti-heartburn drugs in the home setting, usually by self-administration. The home care nurse can assist patients by providing information about taking the drugs correctly and monitoring responses.

Overuse of Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in the Critical Care Setting and Beyond

by FARRELL, C. P.

Journal of Critical Care, 2010, 25(2), 214-220

A retrospective review of 210 patients indicated that 87.1% of all critical care admissions received stress ulcer prophylaxis (SUP). In patients with no risk factors, more than two thirds received SUP on critical care admission; more than three fifths continued on treatment on transfer from the area, and nearly one third were discharged home on SUP without a new indication. Although SUP in high-risk patients can decrease the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, inappropriate use of this regimen may increase drug reactions, needless hospital costs, and personal monetary drain on patients after discharge for over-the-counter drug purchases. The findings maintained that improvement measures to reduce overuse of SUP and to prompt discontinuation before hospital discharge were necessary.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE: Patients admitted to the critical care units are susceptible to stress ulcers. People at high risk should receive SUP. However, increased health care costs and increased risk of adverse drug effects result with inappropriate use of SUP in the critical care area or at discharge without clear indications. Nurses should advocate for proper use of SUP in hospitalized patients.

Adverse Effects

Aluminum-containing antacids such as Mylanta can cause constipation. Hypophosphatemia and osteomalacia may develop in people who ingest large amounts of aluminum-based antacids over a long period because aluminum combines with phosphates in the GI tract and prevents phosphate absorption. Aluminum compounds are rarely used alone for acid-peptic disorders.

Mylanta also contains magnesium. Antacids with magnesium may cause diarrhea and hypermagnesemia. Older adults may experience neuromuscular effects.

Contraindications

People with any signs of appendicitis or inflamed bowel (cramping, soreness, or pain in the lower abdomen) patients with renal failure should not take Mylanta.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Because antacids are minimally absorbed, few drugs alter their effects. Anticholinergic drugs (e.g., atropine) increase effects by delaying gastric emptying and by decreasing acid secretion themselves. Cholinergic drugs (e.g., dexpanthenol [Ilopan]) decrease effects of antacids by increasing GI motility and rate of gastric emptying. No herbs are known to alter the effects of antacids.

However, antacids may prevent absorption of most drugs taken at the same time, including benzodiazepine antianxiety drugs, corticosteroids, digoxin, H2RAs (e.g., cimetidine), iron supplements, phenothiazine antipsychotic drugs, phenytoin, fluoroquinolone antibacterials, and tetracyclines. Antacids increase absorption of a few drugs including levodopa, quinidine, and valproic acid. To avoid or minimize these interactions, it is necessary to separate administration times by 1 to 2 hours.

Administering the Medication

Typical prescribing practices with Mylanta and other antacids used to treat active ulcers is to take them 1 hour and 3 hours after meals and at bedtime for greater acid neutralization. This schedule is effective but inconvenient for many patients. More recently, lower doses taken less often have been found effective in healing duodenal or gastric ulcers, although less acid neutralization occurs.

Authorities once thought that liquid antacid preparations were more effective. Now they consider tablets to be as effective as liquids.

QSEN Safety Alert

It is important to shake liquid antacid preparations well before measuring each dose, because these suspensions require thorough mixing.

Assessing for Therapeutic Effects

The nurse assesses for decreased epigastric pain in patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers or decreased heartburn in those with GERD. Antacids should relieve pain within a few minutes. Also, it is necessary to assess for decreased GI bleeding (e.g., absence of visible or occult blood in vomitus, gastric secretions, or feces). In addition, the nurse uses pH testing to evaluate the quantity, frequency, and duration of acid-reflux episodes, as well as to check the pH of gastric contents. The minimum acceptable pH with antacid therapy is 3.5. Healing usually occurs within 4 to 8 weeks. Finally, the nurse assesses for radiologic or endoscopic reports of ulcer healing.

Assessing for Adverse Effects

With antacids containing magnesium, such as Mylanta, the nurse assesses for diarrhea and hypermagnesemia. Combining such an antacid with one that contains aluminum or calcium may prevent this. Hypermagnesemia may occur in patients with impaired renal function. With the antacid Titralac (Tums), which contains calcium, it is important to observe for constipation. (Combining this antacid with other antacids containing magnesium may prevent this effect.)

Patient Teaching

Box 35.2 summarizes patient teaching information for antacids.

BOX 35.2 Patient Teaching Guidelines: Drugs Used for Peptic Ulcer Disease and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Patient Teaching Guidelines: Drugs Used for Peptic Ulcer Disease and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease