Identify the common causes of diarrhea.

Identify patients at risk for development of diarrhea.

Identify patients at risk for development of diarrhea.

Describe opioid-related antidiarrheal agents in terms of the prototype, indications and contraindications for use, routes of administration, and major adverse effects.

Describe opioid-related antidiarrheal agents in terms of the prototype, indications and contraindications for use, routes of administration, and major adverse effects.

Identify adjuvant drugs used to manage diarrhea.

Identify adjuvant drugs used to manage diarrhea.

Understand how to use the nursing process in the care of patients receiving drug therapy for diarrhea.

Understand how to use the nursing process in the care of patients receiving drug therapy for diarrhea.

Clinical Application Case Study

Joseph Mendoza is a 47-year-old salesman who travels extensively as part of his job. He returned from a trip to Asia 2 days ago, and since his return, he has had abdominal cramping and bloating and an average of four watery bowel movements per day. Mr. Mendoza comes to the clinic seeking advice about how to manage his symptoms. He denies nausea and vomiting. His vital signs are temperature 99.4°F, pulse 82 beats/min, respirations 22 breaths/min, and blood pressure 124/72 mm Hg lying and 120/72 mm Hg standing.

KEY TERMS

Diarrhea: increase in the liquidity of stool or frequency of defecation to more than 3 stools per day

Inflammatory bowel disorders: disorders in which inflamed mucous membranes secrete large amounts of fluids into the intestinal lumen, along with mucus, proteins, and blood; characterized by impaired absorption of water and electrolytes

Irritable bowel syndrome: functional disorder of intestinal motility with no evidence of inflammation or tissue changes

Steatorrhea: loose, fatty stool

Travelers’ diarrhea: form of diarrhea caused by the enterotoxigenic strain of Escherichia coli, typically from fecal contamination of food or water

Introduction

The focus of this chapter is the description of drugs used to relieve the symptoms of diarrhea, specifically the opioid-related agents. Topics of discussion include the general characteristics of these drugs, their mechanisms of action, indications for and contraindications to their use, and their nursing implications. The section on adjuvant medications briefly addresses specific drugs, including antibacterial agents, used to manage underlying disease processes that cause diarrhea.

Overview of Diarrhea

Pathophysiology

Diarrhea, an increase in the liquidity of stool or frequency of defecation to more than 3 stools per day, is a common condition experienced by virtually everyone. It is a symptom of numerous conditions and not a disease. Diarrhea is a manifestation of basic mechanisms that increase bowel motility, cause secretion or retention of fluids in the intestinal lumen (lactose intolerance or toxins such as cholera or laxatives and other drugs), or cause inflammation or irritation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Escherichia coli, Salmonella, rotaviruses, Giardia). It is common for more than one of the mechanisms to be involved in the pathogenesis of a given situation. As a result, bowel contents are rapidly propelled toward the rectum, and absorption of fluids and electrolytes is limited.

Clinical Manifestations

Diarrhea may be acute or chronic and mild or severe. Most episodes of acute diarrhea are defensive mechanisms by which the body tries to rid itself of irritants, toxins, and infectious agents. These episodes of frequent liquid or semiliquid stools are usually self-limiting and subside within 24 to 48 hours without serious consequences. If severe or prolonged, acute diarrhea may lead to serious fluid and electrolyte depletion, especially in young children and older adults. Chronic diarrhea may cause malnutrition and anemia and is often characterized by remissions and exacerbations.

Fever, vomiting, and bloody stools are associated with acute diarrhea, and the presence of these symptoms may help determine the cause. Fever is common and often linked with invasive pathogens. Vomiting is frequently found in illness caused by ingestion of bacterial toxins or viruses. Invasive and cytotoxin-releasing pathogens are known to cause bloody stools, and enterotoxigenic strain E. coli O157:H7 infection is suspected in the absence of fecal leukocytes. Bloody stools are not associated with viral agents and enterotoxins that release bacteria.

Etiology

Some causes of diarrhea include the following:

• Excessive use or abuse of laxatives. Laxative abuse may accompany eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia.

• Undigested, coarse, or highly spiced food in the GI tract. The food acts as an irritant and attracts fluids in a defensive attempt to dilute the irritating agent. This may result from inadequate chewing of food or lack of digestive enzymes.

• Lack of digestive enzymes. Deficiency of pancreatic enzymes inhibits digestion and absorption of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Deficiency of lactase, which breaks down lactose to simple sugars (i.e., glucose and galactose) that can be absorbed by GI mucosa, inhibits digestion of milk and milk products. Lactase deficiency commonly occurs in people of African and Asian descent.

• Intestinal infections with viruses, bacteria, or protozoa. A common source of infection is ingested food or fluid contaminated by a variety of organisms.

• E. coli O157:H7-related hemorrhagic colitis most commonly occurs with the ingestion of under-cooked ground beef. A serious complication of E. coli O157:H7 colitis is hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), characterized by thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and renal failure. Children are especially susceptible to HUS, which is the leading cause of dialysis in pediatric patients. So-called travelers’ diarrhea is usually caused by an enterotoxigenic strain of E. coli (ETEC). Fecal contamination of food or water is the most common source of ETEC-induced diarrhea.

• Consumption of improperly prepared poultry may result in diarrhea due to infection with Campylobacter jejuni. In the United States, this is the most common bacterial organism identified in infectious diarrhea. In addition to diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal discomfort, Campylobacter bacteria produce neurotoxins, which may result in paralysis.

• Salmonella infections may occur when contaminated poultry and other meats, eggs, and dairy products are ingested. Elderly patients are especially susceptible to Salmonella-associated colitis.

• Several strains of Shigella may produce diarrhea. Infection most often results from direct person-to-person contact but may also occur via food or water contamination. Handwashing is especially important in preventing the spread of Shigella from person to person.

• Other diarrhea-producing organisms associated with contamination of specific foods include Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus contamination of raw shellfish and oysters (particularly in the Gulf Coast states), Clostridium perfringens contamination of inadequately heated or reheated meats, Staphylococcus aureus contamination of processed meats and custard-filled pastries, Bacillus cereus contamination of rice and bean sprouts, and Listeria monocytogenes contamination of hot dogs and luncheon meats. Newborns, pregnant women, and older and immunocompromised people are especially susceptible to L. monocytogenes infection.

• Two of the most common viral organisms responsible for gastroenteritis and diarrhea are rotavirus or Norwalk-like virus (calicivirus). Vomiting is usually a prominent symptom accompanying virus-induced diarrhea.

• Inflammatory bowel disorders, such as gastroenteritis, diverticulitis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease. In these disorders, inflamed mucous membranes secrete large amounts of fluids into the intestinal lumen, along with mucus, proteins, and blood, and there is impaired absorption of water and electrolytes. In addition, when the ileum is diseased or a portion is surgically excised, large amounts of bile salts reach the colon, where they act as cathartics and cause diarrhea. Bile salts are normally reabsorbed from the ileum.

• Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder of intestinal motility with no evidence of inflammation or tissue changes. It occurs more commonly in women than in men, affecting approximately 12% of adults in the United States. A change in bowel pattern (constipation, diarrhea, or a combination of both) accompanied by abdominal pain, bloating, and distention are the presenting symptoms. The etiology is unknown; however, activation of 5-HT3 (serotonin) receptors, which affect the regulation of visceral pain, colonic motility, and GI secretions, are thought to be involved in the pathophysiology of IBS.

• Drugs. Many oral drugs irritate the GI tract and may cause diarrhea, including acarbose, antacids that contain magnesium, antibacterials, antineoplastic agents, colchicine, laxatives, metformin, metoclopramide, misoprostol, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tacrine, and tacrolimus. Antibacterial drugs are commonly used offenders that also may cause diarrhea by altering the normal bacterial flora in the intestine.

Antibiotic-associated colitis (also called pseudomembranous colitis) is a serious condition that results from oral or parenteral antibiotic therapy. By suppressing normal flora in the colon, antibiotics allow proliferation of other bacteria, especially gram-positive, anaerobic Clostridium difficile organisms. These organisms produce a toxin that causes fever, abdominal pain, inflammatory lesions of the colon, and severe diarrhea with stools containing mucus, pus, and sometimes blood. Symptoms may develop within a few days or several weeks after the causative antibiotic is discontinued. Other enteric pathogens that may overgrow in the presence of antibiotic therapy and result in colitis include Salmonella, C. perfringens type A, S. aureus, and Candida albicans. Antibiotic-associated colitis is more often associated with ampicillin, cephalosporins, and clindamycin but may occur with any antibiotic or combination of antibiotics that alters intestinal microbial flora.

• Intestinal neoplasms. Tumors may increase intestinal motility by occupying space and stretching the intestinal wall. Diarrhea sometimes alternates with constipation in colon cancer.

• Functional disorders. Diarrhea may be a symptom of stress or anxiety in some patients. No organic disease process can be found in such circumstances.

• Hyperthyroidism. This condition increases bowel motility.

• Surgical excision of portions of the intestine, especially the small intestine. Such procedures decrease the absorptive area and increase fluidity of stools.

• Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Diarrhea occurs in most patients with HIV infection, often as a chronic condition that contributes to malnutrition and weight loss. It may be caused by drug therapy, infection with a variety of microorganisms, or other factors.

Nondrug Therapy

In most cases of acute, nonspecific diarrhea in adults, fluid losses are not severe, and patients need only simple replacement of fluids and electrolytes to replace those lost in the stool. Acceptable replacement fluids during the first 24 hours include clear liquids (e.g., flat ginger ale, decaffeinated cola drinks or tea, broth, gelatin)—2 to 3 L. Also, a diet consisting of bland foods (e.g., rice, soup, bread, salted crackers, cooked cereals, baked potatoes, eggs, applesauce) is best. People may resume their regular diet after 2 or 3 days.

Drug Therapy

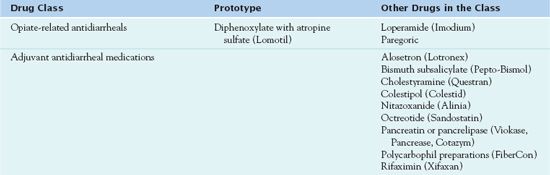

Antidiarrheal drugs include a variety of agents, most of which are discussed in other chapters. When used for treatment of diarrhea, health care providers may give the drugs to relieve the symptom or the underlying cause of the symptom. Overall, opiates and opiate derivatives (see Chap. 48) are the most effective agents for symptomatic treatment of diarrhea. Although morphine, codeine, and related drugs are effective in relieving diarrhea, they are rarely used for this purpose because of their adverse effects. The synthetic drugs diphenoxylate and loperamide have replaced these drugs. Uses include only treatment of diarrhea; they do not cause morphine-like adverse effects in recommended doses. Diphenoxylate requires a prescription. Table 38.1 summarizes drugs used to manage diarrhea.

Opiate-Related Antidiarrheal Agents

The oral opioid  diphenoxylate with atropine (Lomotil) is the prototype used to treat moderate to severe diarrhea. It is a schedule IV controlled substance.

diphenoxylate with atropine (Lomotil) is the prototype used to treat moderate to severe diarrhea. It is a schedule IV controlled substance.

Pharmacokinetics

Diphenoxylate with atropine is well absorbed by the oral route with an onset of action of 45 to 60 minutes. The duration of action is 3 to 4 hours. The drug is metabolized in the liver to active metabolites and is excreted in bile and feces.

Action

Diphenoxylate with atropine slows peristalsis by acting on the smooth muscles in the intestine.

Use

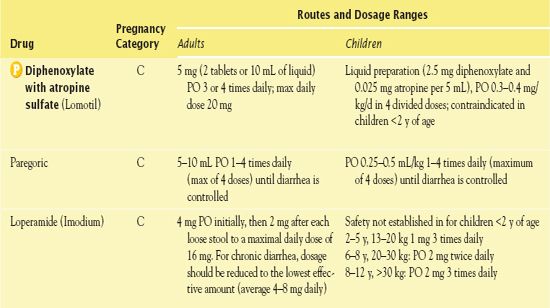

Prescribers order diphenoxylate with atropine to treat diarrhea. Table 38.2 provides dosage information for diphenoxylate with atropine and other opiate-related drugs.

TABLE 38.2

TABLE 38.2

Use in Children

Signs of atropine overdose may occur with usual doses with diphenoxylate, which contains atropine. Children younger than 2 years of age should not take the drug, and those younger than 6 years of age should not take it, except with a pediatrician’s supervision. Even older children should not generally use it for longer than 2 days.

Use in Older Adults

Diarrhea is less common than constipation in older adults, but it may occur from laxative abuse and bowel-cleansing procedures before GI surgery or diagnostic tests. Fluid volume deficits may rapidly develop in older adults with diarrhea. General principles of fluid and electrolyte replacement, measures to decrease GI irritants, and drug therapy apply as for younger adults. Older people may safely take most antidiarrheal drugs, but cautious use is indicated to avoid inducing constipation.

Use in Patients With Renal and/or Hepatic Impairment

Use of diphenoxylate with atropine warrants extreme caution in patients with severe hepatorenal disease because hepatic coma may be precipitated. Care is also necessary in patients with abnormal results of liver function tests.

Use in Patients With Critical Illness

Use of diphenoxylate with atropine requires caution in critically ill patients because they may have renal or hepatic compromise. Episodes of acute diarrhea may be defensive mechanisms by which the body tries to rid itself of irritants, toxins, and infectious agents. Antibacterial drugs administered to the critically ill may cause diarrhea by altering the normal bacterial flora in the intestine. It is important to observe for fluid and electrolyte imbalance and assess the cause of diarrhea before treating the condition. Good handwashing techniques are particularly important in preventing the spread of organisms that can cause diarrhea.

Use in Patients Receiving Home Care

People often take prescription drugs such as diphenoxylate with atropine and over-the-counter antidiarrheal aids in the home setting. The role of the home care nurse may include advising patients and caregivers about appropriate use of the drugs, trying to identify the cause and severity of the diarrhea (i.e., risk of fluid and electrolyte deficit), and teaching strategies to manage current episodes and prevent future episodes.

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects of diphenoxylate with atropine include tachycardia, dizziness, headache, flushing, nausea and vomiting, dry skin and mucous membranes, and urinary retention. Hypotension and respiratory depression have occurred, particularly with doses greater than ordered.

Contraindications

Contraindications to the use of diphenoxylate with atropine include diarrhea caused by toxic materials, microorganisms that penetrate intestinal mucosa (e.g., pathogenic E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella), and antibiotic-associated colitis. In these circumstances, antidiarrheal drugs that slow peristalsis may aggravate and prolong diarrhea.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Increased levels of diphenoxylate with atropine may result with use of methotrimeprazine and pramlintide. Decreased drug levels may result from concurrent use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Use of alcohol may increase central nervous system (CNS) depression. There are no known herbal interactions with diphenoxylate.

Administering the Medication

Administration is oral.

QSEN Safety Alert