Discuss the etiology, physiology, and clinical manifestations for constipation and elimination problems.

Educate patients about nonpharmacologic measures to prevent or treat constipation.

Educate patients about nonpharmacologic measures to prevent or treat constipation.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications of the laxatives.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications of the laxatives.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications of the cathartics.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications of the cathartics.

Identify the prototype, indications, dosages, and routes for the miscellaneous agents used to treat constipation and other conditions.

Identify the prototype, indications, dosages, and routes for the miscellaneous agents used to treat constipation and other conditions.

Understand how to use the nursing process in the care of patients with constipation.

Understand how to use the nursing process in the care of patients with constipation.

Clinical Application Case Study

Doris Campbell, an 84-year-old woman, is complaining about being constipated. Her past health history includes arthritis, osteoporosis, hemorrhoids, and peptic ulcer disease. As a home care nurse, you frequently see patients who complain of constipation.

KEY TERMS

Cathartic: drug with strong laxative effects and elimination of liquid or semiliquid stool

Constipation: infrequent and painful expulsion of hard, dry stools

Defecation: bowel elimination that is normally stimulated by movements and reflexes in the gastrointestinal tract

Flatulence: expulsion of gas through the rectum

Impaction: mass of hard, dry stool in the rectum; caused by chronic constipation

Laxative: drug with mild effects and elimination of soft, formed stool

Introduction

Constipation is a symptom, not a disease. It is the infrequent and painful expulsion of hard, dry stools. Generally, constipation is difficult to define clearly because normal frequency of stools varies as a symptom and differs from person to person. Drug therapy for constipation and elimination problems includes laxatives and cathartics, which are used to promote bowel elimination (defecation). The term laxative implies mild effects, with elimination of soft, formed stool. The term cathartic implies strong effects, with elimination of liquid or semiliquid stool. Although different effects may depend more on the dose than on the particular drug used, the names laxatives and cathartics are used in this chapter to specify the harshness of the level of response expected at normal doses of the drugs.

Overview of Constipation

Etiology

Several risk factors are associated with the development of constipation, including diet and lifestyle, particularly decreased levels of physical activity. Female sex, nonwhite status, advanced age, and low levels of education and income are related risk factors. In addition, certain drugs and disease process are associated with constipation.

Physiology and Pathophysiology

Defecation is bowel elimination that is stimulated by movements and reflexes in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. When the stomach and duodenum are distended with food or fluids, gastrocolic and duodenocolic reflexes cause propulsive movements in the colon, which move feces into the rectum and arouse the urge to defecate. When sensory nerve fibers in the rectum are stimulated by the fecal mass, the defecation reflex causes strong peristalsis, deep breathing, closure of the glottis, contraction of abdominal muscles, contraction of the rectum, relaxation of anal sphincters, and expulsion of the fecal mass.

The cerebral cortex normally controls the defecation reflex so that defecation can occur at acceptable times and places. Voluntary control inhibits the external anal sphincter to allow defecation or contracts the sphincter to prevent defecation. When the external sphincter remains contracted, the defecation reflex dissipates, and the urge to defecate usually does not recur until additional feces enter the rectum or several hours later. In people who often inhibit the defecation reflex or fail to respond to the urge to defecate, constipation develops as the reflex weakens.

Clinical Manifestations

Constipation involves infrequent defecation. Due to variations in diet and other factors, there is no “normal” number of stools, but the traditional medical definition of constipation includes three or fewer bowel movements per week. The use of a multisymptom criterion-based checklist (Rome III criteria for functional constipation) requires two or more of six symptoms during at least one fourth of the bowel movements. Along with fewer than three stools per week, symptoms include straining, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, a sensation of anorectal blockage, hard stools, and use of manual evacuation. Normal bowel elimination should produce a soft, formed stool without pain.

Lifestyle Changes

Nonpharmacologic treatment of people with constipation has included the use of fiber, fluid supplementation, prebiotics, probiotics, and behavioral therapy. There is some evidence that fiber supplements improve the frequency and consistency of stools. No effectiveness data support increasing fluids beyond normal intake or adding behavioral interventions to reduce difficulty in passing stools.

Clinical Application 37-1

Given Mrs. Campbell’s complaint of constipation, what does the nurse assess with regard to the patient’s bowel pattern and risk of constipation?

Given Mrs. Campbell’s complaint of constipation, what does the nurse assess with regard to the patient’s bowel pattern and risk of constipation?

Drug Therapy

Laxatives and cathartics are given to prevent or treat constipation and are somewhat arbitrarily classified as:

• Laxatives: bulk-forming, lubricant or emollient, and surfactant agents (stool softeners)

• Cathartics: saline and stimulant agents

• Miscellaneous agents

Table 37.1 lists the specific drugs used for the treatment of constipation by class.

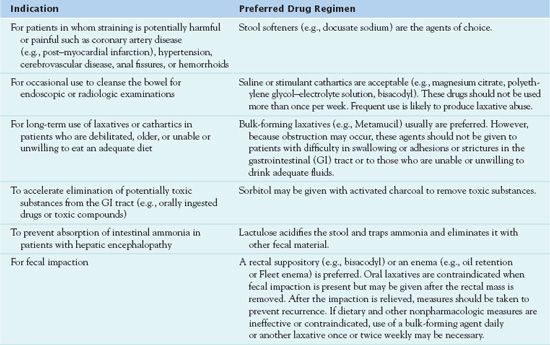

Clinically, the choice of a laxative or cathartic often depends on the reason for use and the patient’s condition, as shown in Table 37.2. There are several indications for use:

• To relieve constipation in pregnant women, elderly patients whose abdominal and perineal muscles have become weak and atrophied, children with megacolon, and patients receiving drugs that decrease intestinal motility (e.g., opioid analgesics, drugs with anticholinergic effects)

• To prevent straining at stool in patients with coronary artery disease (e.g., post-myocardial infarction), hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and hemorrhoids and other rectal conditions

• To empty the bowel in preparation for bowel surgery or diagnostic procedures (e.g., colonoscopy, barium enema)

• To accelerate elimination of potentially toxic substances from the GI tract (e.g., orally ingested drugs or toxic compounds)

• To prevent absorption of intestinal ammonia in patients with hepatic encephalopathy

• To obtain a stool specimen for parasitologic examination

• To accelerate excretion of parasites after anthelmintic drugs have been administered

• To reduce serum cholesterol levels (psyllium products)

Laxatives

Bulk-forming laxatives are soluble fibers that are largely unabsorbed by the intestine. When water is added, these substances swell and become gel-like. Bulk-forming laxatives are the most physiologic laxatives because their effect is similar to that of increased intake of dietary fiber. The bulk-forming laxative  psyllium (Metamucil, others) is the prototype laxative.

psyllium (Metamucil, others) is the prototype laxative.

Pharmacokinetics

Psyllium usually acts within 12 to 24 hours, although it may take as long as 2 to 3 days to exert its full effects. Excretion is in the stool.

Action

Psyllium is essentially unabsorbed by the body. It works by mechanical action to absorb excess water while stimulating normal bowel elimination. The drug adds bulk and size to the fecal mass that stimulates peristalsis and defecation. It also may act by pulling water into the intestinal lumen.

Use

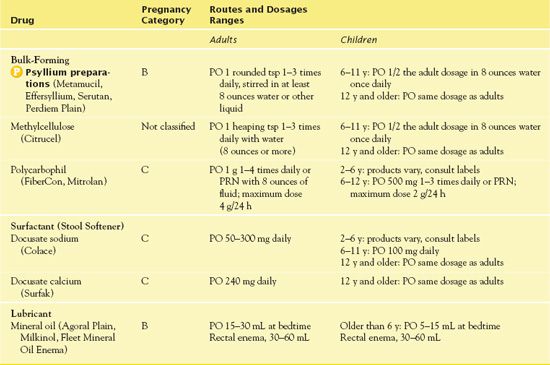

Uses of psyllium include treatment of occasional constipation or bowel irregularity. The drug may also help lower cholesterol when combined with a diet low in cholesterol and saturated fat. It may also be useful in the treatment of diarrhea. It should be noted that because psyllium, like most laxatives, is not absorbed or metabolized extensively, it can usually be used without difficulty in patients with hepatic impairment. Table 37.3 presents route and dosage information for the psyllium and other bulk-forming laxatives as well as surfactant and lubricant laxatives.

TABLE 37.3

TABLE 37.3

Use in Children

Children should obtain adequate fiber from dietary intake. Although psyllium-containing products are available without a prescription, children should take them only under the supervision of a health care provider.

Use in Older Adults

Psyllium is one of the many laxatives that is often used or overused in older adults. Nondrug measures to prevent constipation are much preferred to laxatives in such patients. If a laxative is required on a regular basis, a bulk-forming psyllium compound (e.g., Metamucil) is best because it is most physiologic in its action.

Use in Patients with Critical Illness

Many patients with critical illness, including those with cancer, feel pain and require moderate to large amounts of opioid analgesics for pain control. The analgesics slow GI motility and cause constipation. The reduced mobility and altered bowel regimes that are often found in these patients increase the risk of constipation. Thus, they often need a bowel management program that includes routine administration of laxatives such as psyllium.

Use in Patients Receiving Home Care

Laxatives such as psyllium are commonly self-prescribed and self-administered in the home setting. When visiting patients for purposes other than providing care for patients who take laxatives, the home care nurse may become involved in their use. The functions of the home care nurse may include assessing usual patterns of bowel elimination, identifying patients at risk for constipation, promoting lifestyle interventions to prevent constipation, obtaining laxatives when indicated, and counseling about rational use of laxatives.

Adverse Effects

Psyllium or any fiber product may result in severe gas and bloating. In addition, there have been reports of abdominal cramping and esophageal or bowel obstruction.

Contraindications

Contraindications to the use of psyllium include the presence of undiagnosed abdominal pain. The danger is that the drugs may cause an inflamed organ (e.g., the appendix) to rupture and spill GI contents into the abdominal cavity with subsequent peritonitis, a life-threatening condition. Other contraindications are known allergy to the drug and intestinal obstruction and fecal impaction, a mass of hard, dry stool in the rectum.

QSEN Safety Alert

People who have difficulty swallowing, including those with esophageal stricture or other narrowing 4 or obstruction of the GI tract, should not take psyllium.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

With psyllium, no known drug or herbal interactions exist. However, the laxative may reduce or delay the absorption of certain medications, including carbamazepine, digoxin, lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, and warfarin. People should take psyllium at least 1 hour before or 2 to 4 hours after taking other medications. There is also a potential risk of psyllium interfering with nutrient absorption, but clear evidence is not available.

Administering the Medication

It is important to take the drug with at least 8 ounces of water or another liquid. With the psyllium-containing preparation Metamucil, there have been reports of obstruction in the GI tract when the compound was taken with insufficient fluid. People should take capsules one at a time.

Assessing for Therapeutic Effects

The nurse assesses for relief from constipation within 12 to 72 hours.

Assessing for Adverse Effects

The nurse assesses for choking or trouble swallowing, severe stomach pain or cramping, nausea or vomiting, rectal bleeding, or constipation lasting longer than 7 days.

Patient Teaching

Patients should take the medication as directed with a full glass of liquid, as soon as it is mixed. Maintaining adequate overall intake of fluids also helps improve bowel regularity.

QSEN Safety Alert

Psyllium products may contain sugar, sodium, potassium, or artificial sweeteners. This may be of concern to patients who have diabetes, high blood pressure, renal disease, or phenylketonuria. It is important to teach patients to check the product label if they have these conditions.

Box 37.1 lists patient teaching guidelines for the laxatives and cathartics.

BOX 37.1  Principles and Techniques With Intravenous Drug Therapy

Principles and Techniques With Intravenous Drug Therapy

General Considerations

Diet, exercise, and fluid intake are important in maintaining normal bowel function and preventing or treating constipation.

Diet, exercise, and fluid intake are important in maintaining normal bowel function and preventing or treating constipation.

Eat foods high in dietary fiber daily. Fiber is the portion of plant food that is not digested. It is contained in fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain cereals and breads. Bran, the outer coating of cereal grains such as wheat or oats, is an excellent source of dietary fiber and is available in numerous cereal products.

Eat foods high in dietary fiber daily. Fiber is the portion of plant food that is not digested. It is contained in fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain cereals and breads. Bran, the outer coating of cereal grains such as wheat or oats, is an excellent source of dietary fiber and is available in numerous cereal products.

Drink at least 6 to 10 glasses (8 ounces each) of fluid daily if not contraindicated.

Drink at least 6 to 10 glasses (8 ounces each) of fluid daily if not contraindicated.

Exercise regularly. Walking and other activities aid movement of feces through the bowel.

Exercise regularly. Walking and other activities aid movement of feces through the bowel.

Establish a regular time and place for bowel elimination. The defecation urge is usually strongest after eating and the defecation reflex is weakened or lost if repeatedly ignored.

Establish a regular time and place for bowel elimination. The defecation urge is usually strongest after eating and the defecation reflex is weakened or lost if repeatedly ignored.

Laxative and cathartics use should be temporary and not regular, as a general rule. Regular use may prevent normal bowel function, cause adverse drug reactions, and delay treatment for conditions that cause constipation.

Laxative and cathartics use should be temporary and not regular, as a general rule. Regular use may prevent normal bowel function, cause adverse drug reactions, and delay treatment for conditions that cause constipation.

Never take laxatives and cathartics when acute abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting is present. Doing so may cause a ruptured appendix or other serious complication.

Never take laxatives and cathartics when acute abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting is present. Doing so may cause a ruptured appendix or other serious complication.

After taking a strong laxative or cathartic, it takes 2 to 3 days of normal eating to produce enough feces in the bowel for a bowel movement. Frequent use of a strong laxative promotes loss of normal bowel function, loss of fluids and electrolytes that your body needs, and laxative dependence.

After taking a strong laxative or cathartic, it takes 2 to 3 days of normal eating to produce enough feces in the bowel for a bowel movement. Frequent use of a strong laxative promotes loss of normal bowel function, loss of fluids and electrolytes that your body needs, and laxative dependence.

If one is having chronic constipation and is unable or unwilling to eat enough fiber-containing foods in the diet, the next best action is regular use of a bulk-forming laxative (e.g., Metamucil) as a dietary supplement. These laxatives act the same way as increasing fiber in the diet and are usually best for long-term use. When taken daily, these can prevent constipation. However, these laxatives may take 2 to 3 days to work and are not effective in relieving acute constipation.

If one is having chronic constipation and is unable or unwilling to eat enough fiber-containing foods in the diet, the next best action is regular use of a bulk-forming laxative (e.g., Metamucil) as a dietary supplement. These laxatives act the same way as increasing fiber in the diet and are usually best for long-term use. When taken daily, these can prevent constipation. However, these laxatives may take 2 to 3 days to work and are not effective in relieving acute constipation.

Urine may be discolored if one takes a laxative containing senna (e.g., Senokot). The color change is not harmful.

Urine may be discolored if one takes a laxative containing senna (e.g., Senokot). The color change is not harmful.

Some people use strong laxatives for weight control. This is an inappropriate use and a dangerous practice because it can lead to life-threatening fluid and electrolyte imbalances, including dehydration and cardiovascular problems.

Some people use strong laxatives for weight control. This is an inappropriate use and a dangerous practice because it can lead to life-threatening fluid and electrolyte imbalances, including dehydration and cardiovascular problems.

Self- or Caregiver Administration

Take all laxatives and cathartics as directed and do not exceed recommended doses to avoid adverse effects.

Take all laxatives and cathartics as directed and do not exceed recommended doses to avoid adverse effects.

With bulk-forming laxatives, mix in 8 ounces of fluid immediately before taking and follow with additional fluid, if able. Never take the drug dry. Adequate fluid intake is essential with these drugs.

With bulk-forming laxatives, mix in 8 ounces of fluid immediately before taking and follow with additional fluid, if able. Never take the drug dry. Adequate fluid intake is essential with these drugs.

With bisacodyl tablets, swallow whole (do not crush or chew), and do not take within 1 hour of an antacid or milk. This helps prevent stomach irritation, abdominal cramping, and possible vomiting.

With bisacodyl tablets, swallow whole (do not crush or chew), and do not take within 1 hour of an antacid or milk. This helps prevent stomach irritation, abdominal cramping, and possible vomiting.

Take magnesium citrate or milk of magnesia on an empty stomach with 8 ounces of fluid to increase effectiveness.

Take magnesium citrate or milk of magnesia on an empty stomach with 8 ounces of fluid to increase effectiveness.

Refrigerate magnesium citrate before taking to improve taste and retain effectiveness.

Refrigerate magnesium citrate before taking to improve taste and retain effectiveness.

Mix lactulose with fruit juice, water, or milk, if desired, to improve taste.

Mix lactulose with fruit juice, water, or milk, if desired, to improve taste.

Take lubiprostone (Amitiza) with food.

Take lubiprostone (Amitiza) with food.

Notify your health care provider if severe diarrhea develops while taking lubiprostone.

Notify your health care provider if severe diarrhea develops while taking lubiprostone.