Recognize the etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations of angina.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications for the organic nitrates.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications for the organic nitrates.

Identify the prototype and outline the actions, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the beta-adrenergic blockers.

Identify the prototype and outline the actions, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the beta-adrenergic blockers.

Identify the prototype and describe the actions, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the calcium channel blockers.

Identify the prototype and describe the actions, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the calcium channel blockers.

Apply the nursing process in the care of patients with angina.

Apply the nursing process in the care of patients with angina.

Clinical Application Case Study

Richard Gerald is a 72-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease. He stopped smoking and began a regular exercise program after having a myocardial infarction 3 months ago.

KEY TERMS

Acute coronary syndrome: any condition brought on by sudden, reduced blood flow to the heart

Afterload: amount of vascular resistance that must be overcome to open the aortic (or pulmonic valve on the right side of the heart) and eject the blood with systole

Cardioselectivity: ability of a beta-adrenergic blocker to selectively block beta1 receptors

Intima: inner layer of an artery

Media: middle layer of a vessel

Preload: passive stretch of the ventricles just prior to systole

Introduction

The continuum of coronary artery disease (CAD) progresses from angina to myocardial infarction (MI). There are three main types of angina: stable angina, unstable angina, and variant angina; however, there are also other presentations (Box 26.1). The Canadian Cardiovascular Society classifies patients with angina according to the amount of physical activity tolerated before anginal pain occurs (Box 26.2). These categories can assist in clinical assessment and evaluation of therapy.

This chapter introduces the pharmacological care for the patient experiencing angina. Nonpharmacological treatment measures are also addressed. To understand clinical use of these drugs and nonpharmacological treatment measures, it is necessary to understand the etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations of angina.

BOX 26.1 Types of Angina Pectoris and Their Symptoms

Main Types

Stable

Stable angina (also called classic, typical, or exertional angina) occurs when atherosclerotic plaque obstructs coronary arteries and the heart requires more oxygenated blood than the blocked arteries can deliver. Anginal symptoms, such as chest pressure or pain, are usually precipitated by situations that increase the workload of the heart, such as physical exertion, exposure to cold temperatures, and emotional upset. Recurrent episodes of stable angina usually have the same pattern of onset, duration, and intensity of symptoms. Pain is usually relieved by rest, a fast-acting preparation of nitroglycerin, or both.

Variant

Variant angina (also called Prinzmetal’s, or vasospastic angina) occurs at rest or with minimal exertion, often at night, and results from vasospasm of an epicardial coronary artery. It often occurs at the same time each day. This form of angina is not due to an obstructive atherosclerotic lesion; the spasms of the coronary artery decrease blood flow to the myocardium producing symptoms. Pain is usually relieved by nitroglycerin. Long-term management includes avoidance of conditions that precipitate vasospasm, when possible (e.g., exposure to cold, smoking, emotional stress), as well as antianginal drugs.

Unstable

Unstable angina (also called rest, preinfarction, and crescendo angina) is a type of acute coronary syndrome that falls between classic angina and myocardial infarction. It usually occurs in patients with advanced coronary atherosclerosis and produces increased frequency, intensity, and duration of symptoms. It often leads to myocardial infarction.

Unstable angina usually develops when a minor injury ruptures atherosclerotic plaque. The resulting injury to the endothelium causes platelets to aggregate at the site of injury, form a thrombus, and release chemical mediators that cause vasoconstriction (e.g., thromboxane, serotonin, platelet-derived growth factor). The disrupted plaque, thrombus, and vasoconstriction combine to obstruct blood flow further in the affected coronary artery. When the plaque injury is mild, blockage of the coronary artery may be intermittent and cause silent myocardial ischemia or episodes of anginal pain at rest. Thrombus formation and vasoconstriction may progress until the coronary artery is completely occluded, producing myocardial infarction. Endothelial injury, with subsequent thrombus formation and vasoconstriction, may also result from therapeutic procedures (e.g., angioplasty, atherectomy).

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in its clinical practice guidelines for the management of angina, defines unstable angina as meeting one or more of the following criteria:

Anginal pain at rest that usually lasts longer than 20 minutes

Anginal pain at rest that usually lasts longer than 20 minutes

Recent onset (<2 months) of exertional angina of at least Canadian Cardiovascular Society Classification (CCSC) class III severity

Recent onset (<2 months) of exertional angina of at least Canadian Cardiovascular Society Classification (CCSC) class III severity

Recent (<2 months) increase in severity as indicated by progression to at least CCSC class III

Recent (<2 months) increase in severity as indicated by progression to at least CCSC class III

Because unstable angina often occurs hours or days before acute myocardial infarction, early recognition and effective management are extremely important in preventing progression to infarction, heart failure, or sudden cardiac death.

Other Presentations

Refractory

Chronic stable angina is classified as refractory when it is not controllable by the maximal antianginal drugs, angioplasty, stenting, or coronary artery bypass surgery. The angina can also be classed refractory in patients where the risks of coronary interventions are unjustified.

Atypical

Patients without traditional substernal chest pain or typical relief with rest or nitroglycerin are classified as having atypical angina. This different presentation is more common in women and those with diabetes, displaying variable pain intensity or thresholds, timing, and characteristics. Palpitations and jaw or back pain are confounding complaints. Patients with atypical presentations are less likely to be diagnosed accurately and promptly, often placing them outside the therapeutic window of opportunity to receive appropriate treatment (i.e., thrombolytics and interventional therapies), resulting in poorer outcomes.

Silent Ischemia

Silent myocardial ischemia (also called anginal equivalent) may be painless or silent in a substantial number of patients, particularly in the elderly and those with diabetes. Symptoms other than chest discomfort may be present, including dyspnea, diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting, weakness, and altered sensorium. Patients with silent ischemia are less likely to be diagnosed accurately and promptly, often placing them outside the therapeutic window of opportunity to receive appropriate treatment (i.e., thrombolytics and interventional therapies), resulting in poorer outcomes. Overall, the diagnosis is usually based on chest pain history, electrocardiographic evidence of ischemia, and other signs of impaired cardiac function (e.g., heart failure).

BOX 26.2 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Classification of Patients With Angina Pectoris

Class I: Ordinary physical activity (e.g., walking and climbing stairs) does not cause angina. Angina occurs with strenuous, rapid, or prolonged exertion at work or recreation.

Class II: Slight limitation of ordinary activity. Angina occurs on walking or climbing stairs rapidly, walking uphill, walking or stair climbing after meals, or in cold, in wind, or under emotional stress. Walking more than two blocks on the level and climbing more than one flight of ordinary stairs at a normal pace and in normal conditions can elicit angina.

Class III: Marked limitations of ordinary physical activity. Angina occurs on walking one or two blocks on the level and climbing one flight of stairs in normal conditions and at a normal pace.

Class IV: Inability to carry on any physical activity without discomfort—anginal symptoms may be present at rest.

Overview of Angina

Etiology

Angina pectoris is a common manifestation of CAD. The two main causes of angina are coronary artery spasm and atherosclerotic plaque buildup, which leads to CAD. Other causes of this condition include pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, and pericarditis. Box 26.3 outlines the multiple risk factors associated with the development of CAD.

BOX 26.3 Risk Factors for the Development of Coronary Artery Disease

Modifiable

Abnormal cholesterol levels (high total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [“bad” cholesterol] and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [“good” cholesterol]).

Smoking

Smoking

High blood pressure

High blood pressure

Obesity, especially abdominal obesity

Obesity, especially abdominal obesity

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus

Physical inactivity

Physical inactivity

Nonmodifiable

Increased age

Increased age

Male sex

Male sex

Ethnicity (African Americans have a higher risk of developing high blood pressure, a known contributor to coronary artery disease)

Ethnicity (African Americans have a higher risk of developing high blood pressure, a known contributor to coronary artery disease)

Genetics (family history a major risk factor)

Genetics (family history a major risk factor)

Pathophysiology

Coronary Artery Disease

In CAD, there is a buildup of lipids and fibrous matter within the coronary artery. Increased blood levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) irritate and damage the inner layer (the intima) of the coronary artery. Once LDL has accumulated and damaged the protective layer of the vessel, fatty streaks form, with foam cells. These fatty streaks are yellow and flat and cause no significant coronary artery obstruction. The body responds by sending smooth muscle cells from the middle layer of the vessel, the media. This engulfs the fatty substance and the foam cells and produces a fibrous tissue, which stimulates calcium deposition. This cycle continues, and the fatty streak and foam cell eventually transform into a fibrous plaque. This forms the fibrous cap, which is made up of smooth muscle cells, macrophages, foam cells, lymphocytes, collagen, and elastin. As the lumen of the vessel becomes smaller and blood is limited, especially during times of high oxygen demand (e.g., with physical exertion) oxygen supply cannot keep up with demand. At this point, the patient may experience stable angina.

Angina pectoris is chest pain related to a lack of blood and oxygen supply to the heart muscle, producing myocardial ischemia. Myocardial oxygen demand surpasses oxygen supply. Catecholamine release along with increased sympathetic tone as seen in tachycardia of any etiology, mental stress, or exertion can lead to ischemia. Furthermore, the development of atherosclerotic plaque, as seen in CAD, narrows the lumen of the artery, which impedes the oxygen-carrying blood flow and further results in angina.

Acute coronary syndrome (any condition brought on by sudden, reduced blood flow to the heart) may be seen when the fibrous cap raptures, exposing thrombogenic material, producing a thrombus within the lumen. At this point, the intraluminal thrombi can occlude arteries outright or will detach, move into the circulation, and eventually occlude smaller, distal branches of the coronary artery causing thromboembolism and likely an acute MI or ST-segment elevation MI.

Coronary Artery Spasm

Coronary artery spasm is a transient, sudden narrowing of one of the coronary arteries. The spasm impedes blood flow through the artery, which in turn results in ischemia, leading to angina. Causes of coronary spasm include alcohol withdrawal, emotional stress, exposure to cold, vasoconstricting medications, and stimulants, such as cocaine.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of angina vary with the type of angina (see Box 26.1). The classic anginal pain is usually described as substernal chest pain of a constricting, squeezing, or suffocating nature. It may radiate to the jaw, neck, or shoulder; down the left or both arms; or to the back. The discomfort is sometimes mistaken for arthritis or for indigestion, because the pain may be associated with nausea, vomiting, dizziness, diaphoresis, shortness of breath, or fear of impending doom. The discomfort is usually brief, typically lasting 5 minutes or less until the balance of oxygen supply and demand is restored. Women, elderly people, and people with diabetes are more likely to have symptoms other than chest pain, including fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Nonpharmacologic management of angina and MI includes risk factor modification, patient education, and revascularization procedures. For patients at any stage of CAD development, irrespective of symptoms of myocardial ischemia, optimal management involves lifestyle changes and medications, if necessary, to control or reverse risk factors for disease progression. According to The Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (NCEP III), metabolic syndrome is a risk factor—actually a group of several cardiovascular risk factors, which are linked with obesity— elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, and elevated fasting glucose. These risk factors frequently contribute to CAD and result in significant morbidity and mortality. A growing body of evidence corroborates that risk factor management in patients with CAD improves survival, enhances quality of life, reduces recurrent events, and decreases the need for revascularization. Thus, efforts to assist patients in reducing blood pressure, weight, and serum cholesterol levels, when indicated, and developing an exercise program are necessary. For patients with diabetes mellitus, glucose and blood pressure control can reduce the microvascular changes associated with the condition.

In addition, people should avoid circumstances known to precipitate acute attacks, and those who smoke should stop. Smoking is harmful because of the following factors:

• Nicotine increases catecholamines which, in turn, increase heart rate and blood pressure.

• Carboxyhemoglobin, formed from the inhalation of carbon monoxide in smoke, decreases delivery of blood and oxygen to the heart, decreases myocardial contractility, and increases the risks of life-threatening cardiac dysrhythmias (e.g., ventricular fibrillation) during ischemic episodes.

• Both nicotine and carbon monoxide increase platelet adhesiveness and aggregation, thereby promoting thrombosis.

• Smoking increases the risks for MI, sudden cardiac death, cerebrovascular disease (e.g., stroke), peripheral vascular disease (e.g., arterial insufficiency), and hypertension. It also reduces HDL cholesterol, the “good” cholesterol.

Additional nonpharmacologic management strategies include surgical revascularization (e.g., coronary artery bypass graft) and interventional procedures that reduce blockages (e.g., percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA], intracoronary stents, laser therapy, rotational atherectomy). Additionally, the use of supersaturated oxygen (SSO2) has shown significant improvement in limiting myocardial damage in patients with anterior MIs, particularly if treatment is started within 6 hours of symptom onset. In the Acute Myocardial Infarction with Hyperoxemic Therapy II (AMIHOT II) trial, infusing SSO2 into the previously blocked artery after performing an angioplasty procedure reduced infarct zone size by 6.5%.

Nonpharmacologic management improves patient outcomes. However, most patients still require antianginal and other cardiovascular medications to manage their disease.

NCLEX Success

1. Mr. Smith, a 52-year-old African American man, is recovering from an acute MI. His father died from an MI at age 44. He has smoked one pack of cigarettes a day for 30 years. Which of the following are unmodifiable risk factors? (Check all that apply)

A. smoking

B. genetics

C. race

D. age

2. A 63-year-old woman continues to complain of chest pain although her cardiac catheterization showed no significant cardiac disease. She notes that the chest pain occurs at the same time each night and typically during the cold weather. What kind of angina is the patient likely experiencing?

A. stable angina

B. unstable angina

C. variant angina

D. acute coronary syndrome

Drug Therapy

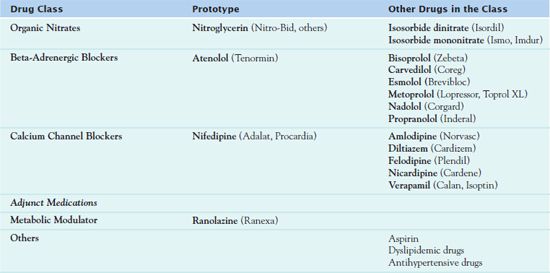

Table 26.1 outlines the drugs used to treat angina pectoris and myocardial ischemia, which include the organic nitrates, beta- adrenergic blockers, and the calcium channel blockers. These drugs relieve anginal pain by increasing blood supply to the myocardium as well as reducing the oxygen demand of the myocardium. This chapter also addresses pharmacologic adjuncts to the management of angina, including a metabolic modulator that increases the energy production of the heart to preserve cardiac function.

Organic Nitrates

The most widely used nitrate is the prototype  nitroglycerin (Nitro-Bid, Nitro-Dur). Available in multiple forms, it is indicated for the management and prevention of acute chest pain caused by myocardial ischemia.

nitroglycerin (Nitro-Bid, Nitro-Dur). Available in multiple forms, it is indicated for the management and prevention of acute chest pain caused by myocardial ischemia.

Pharmacokinetics

Nitroglycerin is 60% bound to protein, undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver, and has a half-life of 1 to 4 minutes. Excretion occurs in the urine. The onset of action, peak, and duration varies with the route of administration.

• Intravenous (IV) drip: onset, immediate; peak, immediate; duration of action, 3 to 5 minutes

• Sublingual (SL): onset, 1 to 3 minutes; peak, 4 to 8 minutes; duration of action, 30 to 60 minutes

• Translingual spray: onset, 2 minutes; peak, 4 to 10 minutes; duration of action, 30 to 60 minutes

• Oral (PO) tablets or capsules (sustained-release): onset, 20 to 45 minutes; peak, 45 to 120 minutes; duration of action, 4 to 8 hours

• Topical ointment: onset, 15 to 60 minutes; peak, 30 to 120 hours; duration of action, 2 to 12 hours

• Topical transdermal disk: onset, 40 to 60 minutes; peak, 60 to 180 minutes; duration of action, 18 to 24 hours

Action

Organic nitrates are converted to nitric oxide, a potent vasodilator, which relaxes smooth muscle in blood vessel walls. Anginal pain is relieved by nitrates by several mechanisms:

• Venous dilation, which reduces venous pressure and decreases venous return to the heart. This decreases blood volume and pressure within the heart (preload), which in turn decreases cardiac workload and oxygen demand. This is the main mechanism by which nitroglycerin relieves angina.

• Coronary artery dilation at higher doses, which can increase blood flow to ischemic areas of the myocardium.

• Arteriole dilation, which lowers peripheral vascular resistance (afterload). This results in lower systolic blood pressure and, consequently, reduced cardiac workload and balancing supply and demand in the heart.

Use

For relief of sudden-onset angina, fast-acting preparations of nitroglycerin include SL and chewable tablets and transmucosal spray. Indications for these preparations include acute-onset chest pain and prophylaxis prior to activities known to provoke angina, such as walking, dancing, or mowing the lawn.

For management of recurrent, chronic angina, long-acting preparations include PO sustained-release tablets and transdermal ointment. With these longer acting forms, intolerance to their hemodynamic effects may develop, and therefore the drugs do not relieve chest pain.

QSEN Safety Alert

To avoid development of tolerance to nitroglycerin, it is essential to observe a 10- to 12-hour nitrate-free interval.

In clinical practice, patients are usually nitrate free during the night, while sleeping. The oral form of the drug undergoes rapid metabolism in the liver, and relatively small portions ultimately reach the systemic circulation. Thus, the PO form does not relieve acute chest pain and may be useful prophylactically in chronic chest pain. Nitroglycerin ointment is indicated for prevention of chronic angina. This route is convenient to use when the patient can have nothing by mouth (NPO) before surgery and cannot take the usually PO dose.

Angina that is unresponsive to SL, PO, or transdermal preparations calls for IV nitroglycerin. Prescribers may typically order the IV form for an MI. IV nitroglycerin is useful in the management of angina that is unresponsive to organic nitrates via other routes or to beta-adrenergic blockers. It also may be used to control blood pressure in perioperative or emergency situations and to reduce preload and afterload in severe heart failure.

National Clinical Guideline Centre. Management of stable angina.

by NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CLINICAL EXCELLENCE (NICE) (CLINICAL GUIDELINE, NUMBER 126)

Retrieved from: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=34825&search=angina

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence published evidence-based clinical practice guidelines regarding management of stable angina based on expert consensus after a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacologic recommendations include the following:

• The use of a beta-blocker or a calcium channel blocker is the first-line treatment for stable angina. The choice of drug is based on contraindications, other medical conditions, and patient preference. Other drugs to treat angina should not be used routinely as first-line treatment. It may be necessary to consider the other drug class if the drug is not tolerated or if symptoms are not adequately managed.

• If a patient must take a beta-adrenergic blocker and calcium channel blocker in combination to manage symptoms, he or she should use a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (nifedipine, amlodipine, or felodipine).

• If either class is not tolerated or contraindicated, the health care provider should consider another drug based on contraindications, other medical conditions, contraindications, cost, and patient preference, such as a long-acting nitrate or ranolazine.

• People who have controlled stable angina with two antianginal drugs should not use a third antianginal drug. However, if symptoms are not adequately controlled, a third antianginal drug may be necessary if the person is awaiting revascularization or if revascularization is not an option.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE: Evidence from a comprehensive review of the literature demonstrates a stepped approach to the management of stable angina. The nurse should be aware of the recommendations when caring for patients with angina.

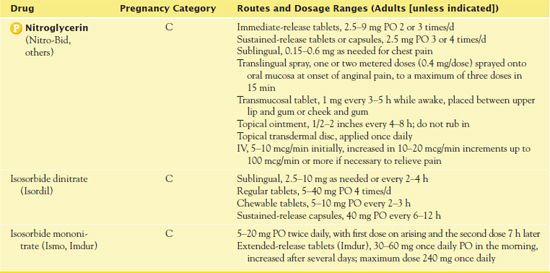

Table 26.2 presents route and dosage information for nitroglycerin and other nitrates.

TABLE 26.2

TABLE 26.2

Use in Children

IV nitroglycerin is the only form of nitroglycerin approved for use in children. It may be used to treat hypertension and heart failure. Caution and close monitoring are necessary.

Use in Older Adults

Older adults may be more vulnerable to hypotension when taking nitroglycerin due to volume depletion, concurrent use of other medication, and loss of sympathetic tone.

QSEN Safety Alert

Therefore, older adults may be at greater risk of falling than younger patients at the therapeutic doses of nitroglycerin due to their risk of hypotension.

Use in Patients With Critical Illness

IV nitroglycerin is commonly used in the critical care setting. Angina related to MI may be a patient’s principal issue in the intensive care unit (ICU); however, he or she may also have heart failure, hypertension, renal failure, and/or anemia and therefore could be receiving multiple drugs such as heparin, nitroglycerin, and dobutamine.

QSEN Safety Alert

The nurse must always check IV compatibility when administering drugs by that route.

Close monitoring of vital signs, along with frequent titration of IV medications, is important.

Adverse Effects

The majority of adverse effects of nitroglycerin are related to the hemodynamic changes responsible for preload reduction and vasodilation. The most common adverse effect is a severe headache, which is typically treated with acetaminophen. Other common adverse effects include dizziness, bradycardia, syncope, hypotension, and orthostatic hypotension.

Contraindications

Contraindications to nitroglycerin include hypersensitivity reactions, severe anemia, hypotension, and hypovolemia.

QSEN Safety Alert

Men who take nitroglycerin or any other nitrate should not use phosphodiesterase enzyme type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil (Viagra) and vardenafil (Levitra) for erectile dysfunction.

Nitrates and phosphodiesterase enzyme type 5 inhibitors decrease blood pressure, and the combined effect can produce profound, life-threatening hypotension.

Caution is necessary in the following situations:

• in the presence of head injury or cerebral hemorrhage because it may increase intracranial pressure

• with the use of other antihypertensive agents such as beta-adrenergic blockers. It is essential to observe for extreme episodes of hypotension.

• with renal impairment

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Many drugs interact with nitroglycerin, increasing or decreasing its effects (Box 26.4). Several herbs interact with nitroglycerin and cause profound hypotension or negate the effects of nitroglycerin (Box 26.5).

BOX 26.4  Drug Interactions: Nitroglycerin

Drug Interactions: Nitroglycerin

Drugs That Increase the Effects of Nitroglycerin

Adalat and other calcium channel blockers, alcohol, aripiprazole, benazepril and other angiotensin- converting enzyme inhibitors, codeine and other narcotics, diphenhydramine, tizanidine

Adalat and other calcium channel blockers, alcohol, aripiprazole, benazepril and other angiotensin- converting enzyme inhibitors, codeine and other narcotics, diphenhydramine, tizanidine

Increase the risk of orthostatic hypotension

Sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil

Sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil

Increase the risk of life-threatening hypotension

Drugs That Decrease the Effects of Nitroglycerin

Acetaminophen, chloral hydrate, dihydroergotamine, sulfonylureas, vasopressin

Acetaminophen, chloral hydrate, dihydroergotamine, sulfonylureas, vasopressin

Decrease vasodilating effects

BOX 26.5  Herb and Dietary Interactions: Nitroglycerin

Herb and Dietary Interactions: Nitroglycerin

Herbs and Foods That Increase the Effects of Nitroglycerin

N-Acetyl cysteine

N-Acetyl cysteine

Arginine, folate, vitamin E

Arginine, folate, vitamin E

Hawthorn

Hawthorn

Herbs and Foods That Decrease the Effects of Nitroglycerin

Vitamin C

Vitamin C

Administering the Medication

It is important to take a patient’s vital signs prior to administration of any form of nitroglycerin. The nurse should withhold the medication with hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 or 30 mm Hg below the patient’s normal blood pressure) as well as tachycardia with a heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute.

Administration of SL nitroglycerin or transdermal spray is essential as soon as chest pain develops. If a patient is hospitalized, it is necessary to call the patient’s health care provider and obtain a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) at the onset of chest pain. The SL nitroglycerin container should stay in a dry, cool, dark environment, and replacement every 6 months is necessary. Exposure to light deactivates the nitroglycerin.

Application of nitroglycerin ointment requires using the dose-measuring application papers supplied with ointment. It is necessary to do the following:

• Squeeze the ointment onto a measuring scale printed on paper; typically, this is 1 or 1/2 inch depending on the practitioner’s order.

• Use the paper to spread ointment onto a nonhairy area of skin (chest, abdomen, thighs; avoid distal extremities) in a thin, even layer, covering a 2- to 3-inch area.

• Do not allow the ointment to come in contact with the hand. Do not massage the ointment into the patient’s skin because absorption will be increased and interfere with the sustained action.