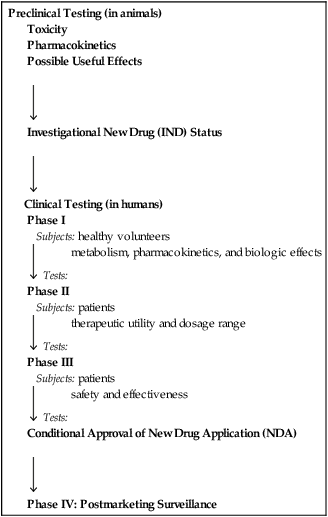

CHAPTER 3 In 1962, Congress passed the Harris-Kefauver Amendments to the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. This law was created in response to the thalidomide tragedy that occurred in Europe in the early 1960s. Thalidomide is a sedative now known to cause birth defects and fetal death. Because the drug was used widely by pregnant women, thousands of infants were born with phocomelia, a rare birth defect characterized by the gross malformation or complete absence of arms or legs. This tragedy was especially poignant in that it resulted from nonessential drug use: The women who took thalidomide could have done very well without it. Thalidomide was not a problem in the United States because the drug never received approval by the FDA (see Chapter 107, Box 107–1). In 1970, Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act (Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act). This legislation set rules for the manufacture and distribution of drugs considered to have the potential for abuse. One provision of the law defines five categories of controlled substances, referred to as Schedules I, II, III, IV, and V. Drugs in Schedule I have no accepted medical use in the United States and are deemed to have a high potential for abuse. Examples include heroin, mescaline, and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Drugs in Schedules II through V have accepted medical applications but also have the potential for abuse. The abuse potential of these agents becomes progressively less as we proceed from Schedule II to Schedule V. The Controlled Substances Act is discussed further in Chapter 37 (Drug Abuse: Basic Considerations). • The fast-track system created for AIDS drugs and cancer drugs now includes drugs for other serious and life-threatening illnesses. • Manufacturers who plan to stop making a drug must inform patients at least 6 months in advance, thereby giving them time to find another source. • A clinical trial database will be established for drugs directed at serious or life-threatening illnesses. These data will allow clinicians and patients to make informed decisions about using experimental drugs. • Drug companies can now give prescribers journal articles and certain other information regarding “off-label” uses of drugs. (An “off-label” use is a use that has not been evaluated by the FDA.) Prior to the new act, clinicians were allowed to prescribe a drug for an off-label use, but the manufacturer was not allowed to promote the drug for that use—even if promotion was limited to providing potentially helpful information, including reprints of journal articles. In return for being allowed to give prescribers information regarding off-label uses, manufacturers must promise to do research to support the claims made in the articles. The testing of new drugs has two principal steps: preclinical testing and clinical testing. Preclinical tests are performed in animals. Clinical tests are done in humans. The steps in drug development are outlined in Table 3–1. TABLE 3–1 The hidden dangers in new drugs are illustrated by the data in Table 3–2. This table presents information on 11 drugs that were withdrawn from the U.S. market soon after receiving FDA approval. In all cases, the reason for withdrawal was a serious adverse effect that went undetected in clinical trials. Admittedly, only a few hidden adverse effects are as severe as the ones in the table. Hence, most do not necessitate drug withdrawal. Nonetheless, the drugs in the table should serve as a strong warning about the unknown dangers that a new drug may harbor. TABLE 3–2 Some New Drugs That Were Withdrawn from the U.S. Market for Safety Reasons

Drug regulation, development, names, and information

Landmark drug legislation

New drug development

Stages of new drug development

Preclinical Testing (in animals)

Toxicity

Pharmacokinetics

Possible Useful Effects

Investigational New Drug (IND) Status

Clinical Testing (in humans)

Phase I

Subjects: healthy volunteers

Tests: metabolism, pharmacokinetics, and biologic effects

Tests: metabolism, pharmacokinetics, and biologic effects

Phase II

Subjects: patients

Tests: therapeutic utility and dosage range

Tests: therapeutic utility and dosage range

Phase III

Subjects: patients

Tests: safety and effectiveness

Tests: safety and effectiveness

Conditional Approval of New Drug Application (NDA)

Phase IV: Postmarketing Surveillance

Limitations of the testing procedure

Failure to detect all adverse effects

Drug

Indication

Year Introduced/Year Withdrawn

Months on the Market

Reason for Withdrawal

Rotigotine* [Neupro]

Parkinson’s disease

2007/2008

10

Patch formulation delivered erratic dosages

Natalizumab† [Tysabri]

Multiple sclerosis

2004/2005

3

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Rapacuronium [Raplon]

Neuromuscular blockade

1999/2001

19

Bronchospasm, unexplained fatalities

Alosetron† [Lotronex]

Irritable bowel syndrome

2000/2000

9

Ischemic colitis, severe constipation; deaths have occurred

Troglitazone [Rezulin]

Type 2 diabetes

1999/2000

12

Fatal liver failure

Grepafloxacin [Raxar]

Infection

1997/1999

19

Severe cardiovascular events, including seven deaths

Bromfenac [Duract]

Acute pain

1997/1998

11

Severe hepatic failure

Mibefradil [Posicor]

Hypertension, angina pectoris

1997/1998

11

Inhibits drug metabolism, causing toxic accumulation of many drugs

Dexfenfluramine [Redux]

Obesity

1996/1997

16

Valvular heart disease

Flosequinan [Manoplax]

Heart failure

1992/1993

4

Increased hospitalization; decreased survival

Temafloxacin [Omniflox]

Infection

1992/1992

4

Hypoglycemia; hemolytic anemia, often associated with renal failure, hepatotoxicity, and coagulopathy ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree