Chapter 55 Medical disorders of pregnancy

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

Midwives are mainly concerned with normal pregnancy; however, they must be aware of pre-existing conditions which make a woman unsuitable for booking in a low-risk environment and be able to recognize signs of deterioration in a woman’s condition, and know what action to take (Lewis 2007, NMC 2008). With modern treatment, many women with medical conditions who previously would not have reached childbearing age, now do so. Trends in childbearing also show that women are having children at a later age, by which time they may have developed medical conditions such as heart disease, hypertension and diabetes which are associated with unhealthy lifestyles and obesity (Lewis 2008). Lewis also suggests that while health professionals have given effective attention to the ‘big obstetric killers’ such as haemorrhage, sepsis and pre-eclampsia, more women now die from indirect causes relating to their medical conditions (Lewis 2008).

Women with pre-existing medical conditions have often received lifelong treatment and are experts in their own care and treatment. They will often be familiar with a medical team, and may have received pre-conception advice prior to planning the pregnancy. More rarely, they may have received advice against becoming pregnant and may be considering a termination, or have deliberately decided to embark on a pregnancy regardless of personal risk. Whether or not the pregnancy continues, women with complicated pregnancies report that they feel ‘out of control’ and experience high levels of anxiety. They feel the focus of pregnancy is on the fetus and once the baby is born, care is not so intense, so they feel isolated in the postnatal period (Spencer 2007, Thomas 1999).

An in-depth approach to all medical conditions is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, a range of medical conditions is considered, all of which, if disclosed at the antenatal booking interview, require a multidisciplinary approach (NICE 2008a). It cannot be overemphasized that some of the signs and symptoms associated with severe maternal illness, such as breathlessness and heartburn, are common towards term in a normal pregnancy, which is why they can be easily overlooked or disregarded (Lewis 2007).

Anaemia

Anaemia is a deficiency in the quality or quantity of red blood cells, resulting in reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. In the UK, NICE guidelines for antenatal care indicate that routine iron supplementation during pregnancy is unnecessary, suggesting that investigations and/or supplementation are warranted only when haemoglobin levels are lower than 11 g/dL at first contact, and 10.5 g/dL at 28 weeks (NICE 2008a). However, Evans (2008) suggests that iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) has a profound impact on women’s lives throughout the lifespan, and that postnatal anaemia contributes to poor health and low mood which is frequently overlooked. Work from the World Health Organization (WHO) also highlights the risks of anaemia to pregnant and non-pregnant women (WHO 1992), and this was illustrated by data gathered by McLean et al (2007) which plotted the prevalence of anaemia in children and women of reproductive age throughout the world, indicating the highest rates in the African and Indian continents.

Iron deficiency anaemia

Investigations

After taking a detailed history about general health, diet, infection, blood loss and other relevant information, further investigations such as haemoglobin level, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), packed cell volume (PCV), total iron binding capacity, and serum ferritin will give a full picture (McKay 2000, NICE 2008a) (see Ch. 33).

Management

Where iron deficiency anaemia has been diagnosed, oral iron 120–140 mg daily may be given as:

Women need to know that iron absorption is enhanced by vitamin C and inhibited by tannin in tea, and that there might be some side-effects, such as blackness of stools, nausea, epigastric pain, diarrhoea and constipation. Side-effects may be reduced by taking the iron after meals, although this decreases iron absorption. It may be better tolerated at bedtime, and by leaving 6 to 8 hours between doses. However, the type and dose may need to be changed if symptoms persist (Jordan 2002). This is also a good opportunity for the midwife to provide dietary advice (see Ch. 17).

In more severe cases of anaemia, the woman may be given intramuscular injections of iron. Special precautions should be taken when administering this, to avoid permanent staining of the skin (Jordan 2002).

Folic acid deficiency anaemia

Management

Dietary sources of folic acid are lightly cooked green leafy vegetables, such as broccoli and spinach (see Ch. 17). Following the demonstrated link between neural tube defects and intake of folic acid, all pregnant women, and those intending to become pregnant, are advised to take 0.4–4 mg folic acid daily (NICE 2006).

Haemoglobinopathies

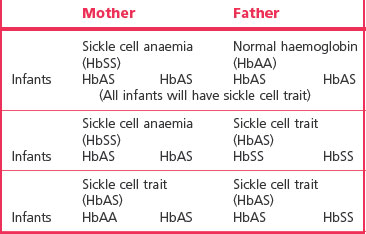

Haemoglobinopathies are inherited conditions in which one or more abnormal types wholly or partly replace normal adult haemoglobin, HbA. The main haemoglobinopathies which complicate pregnancy are sickle cell disease and thalassaemia. These conditions are genetically complex and are presented here in a simplified form, with patterns of inheritance illustrated in Tables 55.1. and 55.2.

Table 55.1 Haemoglobin combination in sickle cell disorders

| HbSS | Homozygous sickle cell disease (sickle cell anaemia) |

| HbSC | Heterozygous sickle cell disease (sickle cell C disease) |

| HbCC | Homozygous CC disease (not a sickling disorder) |

| HbS beta/thal | Sickle/beta thalassaemia |

| HbAS | Sickle cell trait |

Sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease

In sickle cell disease, erythrocytes containing HbS have a short lifespan of 5–10 days (rather than the normal span of 120 days). ‘Sickling’ occurs when cells become sickle shaped under conditions of low oxygen tension, including hypoxia, dehydration, infection, acidosis and cold (Dike 2007, Nelson-Piercy 2006). Cells are easily haemolysed and cause extremely painful vaso-occlusive symptoms in joints, in the abdomen and in the extremities during acute exacerbations, known as a crisis. This leads to chronic haemolytic anaemia, and an increase in the rate of haemoglobin synthesis in the bone marrow, which may lead to folic acid deficiency. Other complications are thromboembolic disorders, retinopathy, renal papillary necrosis, leg ulcers, and increased risk of infection because of disorders in the function of the spleen (Dike 2007, Nelson-Piercy 2006). Acute chest syndrome may occur, in which there is pyrexia, tachypnoea, leucocytosis and pleuritic chest pain.

Effect on pregnancy

The diagnosis is usually made in childhood, once most fetal haemoglobin (HbF) has been replaced, and all women at risk should be tested. Nelson-Piercy (2006) observes that 35% of pregnancies will be complicated by crises, and perinatal mortality is increased four- to sixfold. Pregnancy may be complicated by increased risk of miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preterm labour, and pre-eclampsia.

Management

Pregnancy

Women with sickle cell disease may have poor appetites and need to have regular small meals including meat, fish, eggs, cheese, fruit and wholemeal bread. They should be aware of the symptoms of infection, and who to contact if they feel unwell. In the case of a crisis, the woman will be admitted to hospital, where she should be kept warm, and given pain relief, usually morphine (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Oxygen levels are monitored by pulse oximetry or arterial blood gases.

Heart disease

Heart disease is the leading non-obstetric cause of maternal death in the UK, with 48 maternal deaths reported in the triennium 2003–2005 (Lewis 2007). Myocardial infarction is the most common cardiac cause of maternal death. The total incidence of cardiac disease in pregnancy is 0.5–2% (McLean et al 2008).

Signs and symptoms of cardiac disease are:

During pregnancy, women with pre-existing heart disease may experience a worsening of symptoms, due to physiological changes of pregnancy (see Ch. 31). There is an increase in circulating blood volume, increased resting oxygen consumption, decreased peripheral vascular resistance, an increase in stroke volume and a slight increase in resting heart rate (Adamson et al 2007). These changes influence haemodynamics, increasing strain on the heart, which is further compromised during labour. A wide range of conditions affect the heart in a mild, moderate or severe way, and conditions may be congenital or acquired, as outlined below.

Congenital heart disease

Congenital defects relate to the structure of the heart, and the most common are atrial septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and ventricular septal defects. Other more serious lesions include Fallot’s tetralogy (ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, overriding aorta and right ventricular hypertrophy) and Eisenmenger’s syndrome (ventricular septal defect, overriding aorta and right ventricular hypertrophy). Most lesions are corrected by surgery in childhood. Marfan’s syndrome is a genetic condition in which cardiac anomalies occur. Pregnancy outcome is worst where there is pulmonary hypertension in Eisenmenger’s syndrome and in Marfan’s syndrome where there is aortic involvement (Adamson et al 2007). Many pre-existing cardiac disorders are complex, and pre-pregnancy counselling is essential, so that women know their own health status in relation to likely outcome. Some women, particularly those with cyanotic heart disease and pulmonary hypertension, may be advised to avoid pregnancy, or, if pregnant, may be advised to have termination of pregnancy (Adamson et al 2007). However, the woman’s choice must be respected.

Acquired heart disease

This usually involves damage to heart valves, such as stenosis, where the valve is constricted, or incompetence, where the valve fails to close completely. Valvular problems are often subsequent to infection or rheumatic heart disease, now rare in the UK but prevalent in developing countries, and a problem for immigrant mothers (Lewis 2007). Women who have had valve replacements will be on anticoagulant therapy, and choices need to be made to balance the need for anticoagulants against the risks they pose for the fetus. Warfarin is teratogenic in early pregnancy and may lead to fetal haemorrhage at any time. There is considerable debate about appropriate combinations of warfarin and heparin and whether fetal risks may be reduced by changing to self-administered subcutaneous or intravenous heparin, which does not cross the placenta, after the first trimester (Adamson et al 2007). The effects of heparin are reversed by protamine sulphate.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a rare, functional, cardiac complication, with sudden cardiac failure, arising in the last month of pregnancy or in the first 5 months postpartum, where there has been no evidence of heart disease pre-pregnancy. It is more common in women of black race, multiparity, and higher maternal age, and is a significant cause of maternal mortality (Adamson et al 2007, Lewis 2007, McLean et al 2008).

Antenatal care

Pre-pregnancy counselling and then care in a dedicated antenatal cardiac clinic are required, with input from obstetrician, cardiologist, anaesthetist and midwife (Adamson et al 2007).

Labour

Depending on the type of cardiac disorder and the progress of the pregnancy, labour may be spontaneous or induced or an elective caesarean section may be carried out. Prophylactic antibiotics may be given to reduce the risk of bacterial endocarditis (Adamson et al 2007). Epidural analgesia is recommended, but with caution in regard to hypotension, and it is contraindicated in women on anticoagulant therapy. The optimum position for the woman is the ‘cardiac position’ supported left lateral, or semi-upright, with the legs lower than the abdomen (Adamson et al 2007). In addition to usual midwifery observations in labour, the following are important:

In the absence of obstetric complications, vaginal delivery causes less haemodynamic fluctuation than caesarean section (Adamson et al 2007).

There is no reason for elective instrumental delivery if birth is proceeding well; however, excessive pushing should be avoided since it alters haemodynamics and may compromise cardiac activity. If the woman feels the urge to push, short pushes with the mouth open should be encouraged. Sudden strong uterine contraction in the third stage may direct so much of the uterine circulation of blood to the systemic circulation that the impaired heart may become seriously compromised, therefore ergometrine and syntometrine are not used. Syntocinon should be used with caution, and is contraindicated in cases of heart failure (Adamson et al 2007).

Thyroid disorders

Thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism, Graves’ disease)

Thyrotoxicosis occurs in about 1 : 500 pregnancies, with 95% of these associated with an autoimmune disorder in which thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor antibodies are produced. When untreated, the condition is associated with infertility, but conception occurs commonly in women who are treated. The condition does not appear to be made worse by pregnancy (Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree