Colorectal Adenocarcinoma

Surgical Management: Colon Cancer

Surgical Management: Rectal Cancer

Adjuvant and Neoadjuvant Therapy

Other Cancers of the Colon and Rectum

Other Cancers of the Colon and Rectum

Melanoma: Primary and Metastatic

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

Indications for Stoma Formation for Colorectal Neoplasia

Indications for Stoma Formation for Colorectal Neoplasia

In the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common malignancy and second most common cause of cancer-related death (Howlander et al., 2014). Fortunately, due to significant efforts in both screening and treatment, those rates are decreasing on the order of 3.1% and 2.8% yearly for CRC incidence and deaths, respectively (National Cancer Institute, 2014). Despite these promising trends, there will be an estimated 136,830 new cases of colon cancer in 2014, making care of the colorectal patient in need of either temporary or permanent stoma a very common occurrence in clinical practice.

Colorectal Adenocarcinoma

Etiology

Adenocarcinoma accounts for the majority of cancers in the colon and rectum. The development of these tumors is believed to be from a single transformed cell that undergoes abnormal growth and division leading to formation of an adenoma and ultimately adenocarcinoma. In order to progress to carcinoma, the cell must undergo a series of genetic mutations causing inactivation of tumor suppressor genes such as APC, DDC, and p53 or activation of protooncogenes like K-ras, which is associated with poor prognosis (Conlin et al., 2005).

Risk Factors

There are both modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for CRC development. Modifiable risk factors include high-fat and/or low-fiber diet, decreased physical activity, and associated obesity (American Cancer Society, 2014). Nonmodifiable risk factors include age >50 years, patient disease, family history of polyps or CRC, and genetic predisposition. Patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (i.e., Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) are at increased risk of developing CRC with a lifetime risk of 3.7% to 5.4% (Eaden et al., 2001). Their risk is proportional to the duration of inflammation, extent of colonic involvement, and age of onset. Personal history of neoplastic polyps (i.e., adenomas) carries a two- to fivefold increased risk of carcinoma, which is not surprising given the natural history of CRC development. A family history of adenoma or CRC yields a two- to fourfold increased risk of CRC, with greater risk for CRC over adenoma, family age of diagnosis at <50 years, and multiple affected family members (Johns & Houlston, 2001).

CLINICAL PEARL

People with a history of colorectal cancer in one or more first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, or children) are at increased risk.

While the majority of CRCs are sporadic, approximately 15% are associated with an inherited colon cancer predisposition via a germline genetic mutation. Such syndromes include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC). FAP is caused by mutations in the oncogene APC and is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with a 100% risk of developing colon cancer by age 40 years. Individuals with FAP develop hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps in the colon and in the duodenum and stomach. Each of these is at risk for malignant transformation. Individuals with FAP should undergo total colectomy or proctocolectomy for treatment and risk reduction rather than segmental resection alone. There is a high risk of recurrence in the rectum if proctectomy is not performed, and therefore these individuals must continue rectal screening postoperatively.

HNPCC (Lynch Syndrome) is inherited by mutations in one of several mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2) leading to microsatellite instability. It is estimated that HNPCC accounts for 5% of CRCs. The lifetime CRC risk is slightly lower than with FAP at a rate of 70% to 90%. These individuals do not develop diffuse adenomatous disease as with FAP, and the cancers are typically flat and difficult to detect by colonoscopy. These tumors have a predilection for the right colon and can be treated with total colectomy alone without proctectomy as with FAP. Additionally, they are at risk for extracolonic cancers such as endometrial, ovarian, stomach, small bowel, and bladder. Women with HNPCC are counseled to undergo surveillance if premenopausal or consider prophylactic total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy if done with childbearing.

Screening

CRC screening has been a mainstay of health maintenance therapy for decades. The two primary studies are the fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and endoscopy. FOBT is limited in that not all CRCs cause bleeding and only 10% to 15% of individuals with positive FOBT have CRC (Umar et al., 2004). Despite this limitation, even 50% compliance with annual FOBT is estimated to decrease the incidence of CRC by approximately 20% (Hardcastle et al., 1986; Umar et al., 2000). Endoscopic evaluation of the colon is the other primary means of CRC screening, through either sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. These have the advantage of increased sensitivity and specificity as compared to FOBT, but are invasive studies and carry a risk of iatrogenic perforation. Additionally both diagnostic biopsies and therapeutic procedures can be performed. CT colonography and virtual colonoscopy are additional screening modalities that have the benefit of improved visualization of the colonic mucosa without the risks of an invasive procedure. Thus far, these are not routinely used. Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend colonoscopy, annual FOBT, or combination of flexible sigmoidoscopy with FOBT starting age 50 for average-risk individuals (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2014a).

CLINICAL PEARL

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has Colon Cancer Guidelines for Patients (http://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/colon/index.html#1).

Presentation/Workup

If not diagnosed through a screening modality, patients with CRC may present with a variety of symptoms including blood per rectum, decreased stool caliber, nonspecific abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue. Initial evaluation includes endoscopy if not previously performed, to assess tumor location and obtain biopsies to confirm suspected diagnosis of CRC. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, further studies are used to evaluate extent of tumor invasion and tumor spread including CT chest, abdomen and pelvis, CEA, and MRI or endoscopic ultrasound for rectal cancers. Based on this information, the cancer is staged using tumor invasion, spread to lymph nodes, and distant metastatic spread (TNM classification, Table 3-1) (Edge et al., 2010).

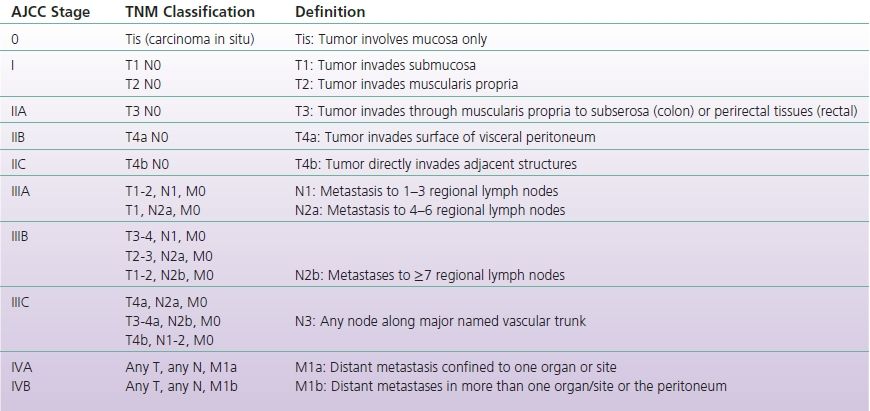

TABLE 3-1 TNM Classification

Adapted from Edge, S. B., Byrd, D., Compton, C., et al. (Eds.). (2010). AJCC cancer staging manual (7th ed.). New York: Springer.

Treatment Algorithms

Based on staging information, specifically local tumor invasion and metastatic disease, patients may be treated with preoperative neoadjuvant therapy or go directly to surgical resection, followed by adjuvant therapy if indicated.

Surgical Management: Colon Cancer

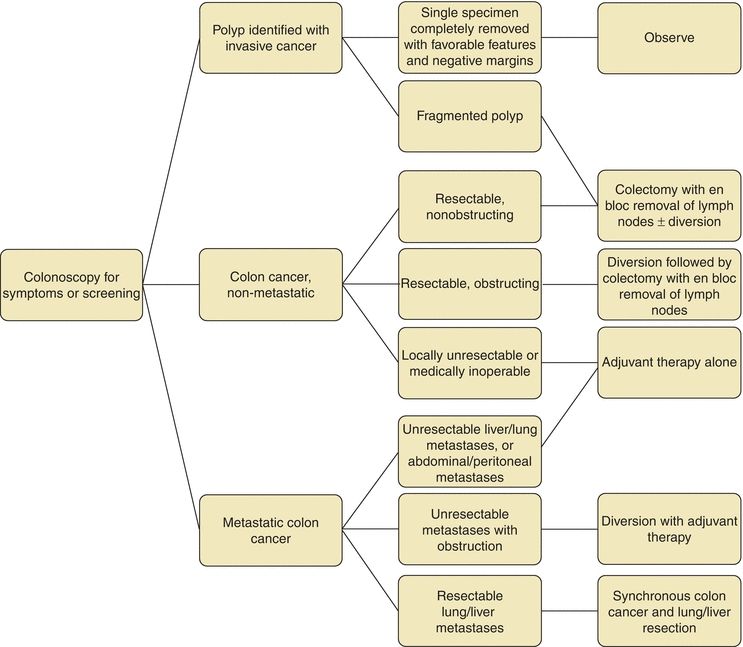

Surgical resection is commonly a first step in the treatment of CRC depending on stage (Figs. 3-1 and 3-2) (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2014b, 2014c). It is estimated that over 200,000 colectomies are performed yearly in the United States, making it one of the most commonly performed procedures (Bal, 1992; Etzioni et al., 2009). A preoperative evaluation must be performed to determine the patient’s fitness for the planned operation. The steps of resection include ligation of the feeding artery with en bloc resection of tumor and involved adjacent structures and inclusion of the draining lymph nodes, followed by primary anastomosis (Fig. 3-3A). Originally it was believed that 5-cm proximal and distal margins were required; however, mural spread rarely extends past 2 cm from the palpable tumor (Quirke et al., 1986). This is often not measured in practice as oncologic principles and blood supply necessitate resection proximally and distally to the next named feeding vessel. Specifically with right colon resections, there is not a set distance of terminal ileum required for adequate resection.

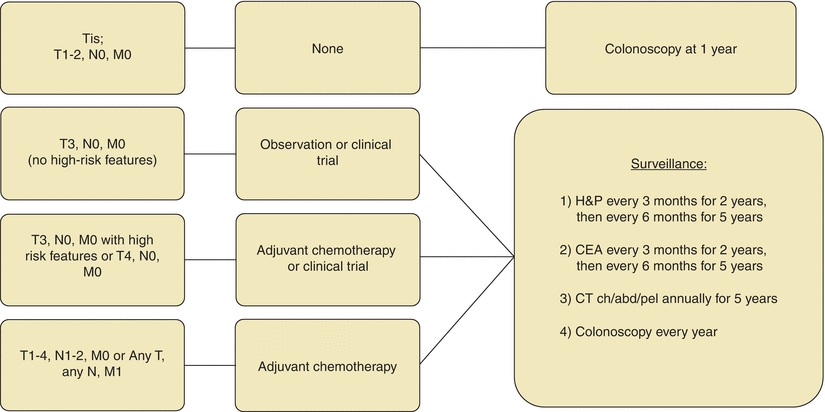

FIGURE 3-1. Treatment algorithm for colon cancer.

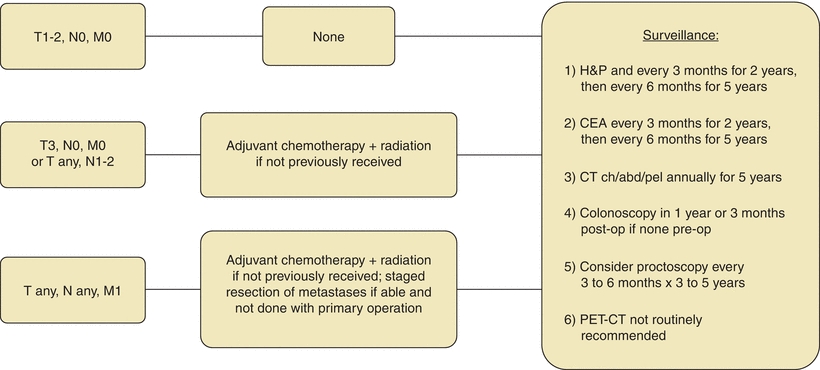

FIGURE 3-2. Treatment algorithm for rectal cancer.

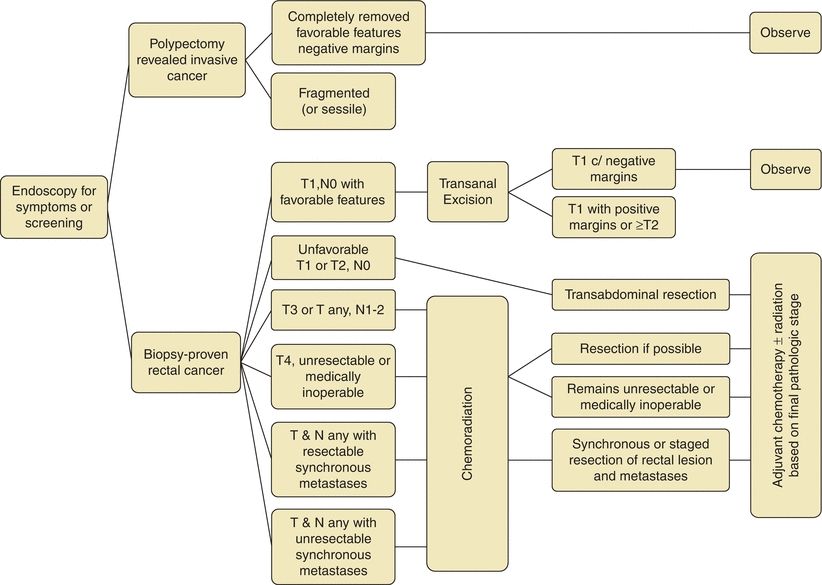

FIGURE 3.3 A. Segmental colon resection for colon cancer based on tumor location. B. LAR for distal colon or mid/upper rectal cancers. C. APR for distal rectal cancer.

Surgical Management: Rectal Cancer

There are important differences for resection of rectal cancers as compared to colon cancers. Colon cancers are treated with segmental colectomy guided by the above described principles. Rectal cancers are treated by one of three operations depending on extent of local disease and tumor location: transanal local excision/transanal endoscopic microsurgery, low anterior resection (LAR), or abdominoperineal resection (APR) (Fig. 3-2). Low-grade, node-negative tumors (T1N0) may be treated with transanal local excision with curative intent. Advanced cancers in the upper and middle third of the rectum are treated with LAR (Fig. 3-3B), while low rectal cancers may require APR (Fig. 3-3C) due to sphincter involvement or inability to obtain clear distal margin. LAR encompasses the sigmoid and involved rectum while leaving distal rectum and sphincter complex intact, whereas resection of the entire rectum and anus and creation of an end colostomy is required with an APR. Both LAR and APR require total mesorectal excision (TME) for adequate oncologic resection, entailing complete resection of mesorectum and other surrounding perirectal tissues. Pathologic specimens are evaluated for adequacy of TME as well as involvement of circumferential radial margin (CRM).

CLINICAL PEARL

When an APR is performed, the left colon is used to create the colostomy, and generally the stoma will be located on the left side of the abdomen.

Adjuvant and Neoadjuvant Therapy

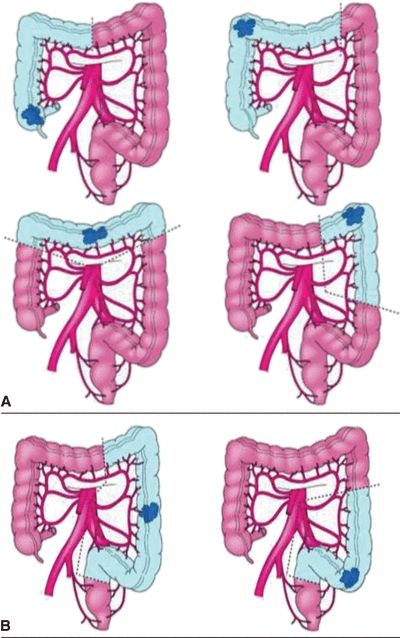

Systemic treatment with chemotherapy is beneficial for patients with locally advanced tumors (T3 with high risk of recurrence or T4) as well as those metastasized to lymph nodes or distant sites (Fig. 3-4). Based on the results of the MOSAIC trial and the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) C-07, the current adjuvant regimen consists of 5-FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) (André et al., 2009; Kuebler et al., 2007). Both overall survival and disease-free survival were improved on the order of 5% on the FOLFOX regimen.

FIGURE 3-4. Adjuvant treatment algorithm for colon cancer.

Radiation therapy is recommended for rectal cancers with advanced local disease or lymph node involvement (Figs. 3-2 and 3-5). For these tumors, the incidence of local recurrence is decreased from 30% to 65% to 5% to 10% with adjuvant radiation (Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group, 2001). Adjuvant radiation of the colon yields less benefit, as there is less overall risk of local recurrence as compared to rectal cancer. Additionally, it presents the risk of radiation toxicity to surrounding structures and organs that are difficult to exclude from the treatment field.

FIGURE 3-5. Adjuvant treatment algorithm for rectal cancer.

Other Cancers of the Colon and Rectum

Although adenocarcinoma is the predominant colorectal neoplasm, there are several other tumors of the colon and rectum that occur with less frequency but may require surgical management and possible stoma formation.

Carcinoid Tumors

Carcinoid tumors are a type of neuroendocrine tumor originating from the crypts of Lieberkühn. Approximately 65% of carcinoid tumors arise within the gastrointestinal tract, 30% of which arise in the colon and 20% in the rectum (Kulke & Mayer, 1999). These tumors are twice as common in individuals of African American descent and occur primarily in the fifth or sixth decades of life. Carcinoid syndrome is present in 10% to 18% of patients with symptoms including flushing, watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, wheezing, and right-sided heart failure. Unfortunately, 90% of symptomatic patients already have advanced or metastatic disease. Colorectal carcinoids are more commonly asymptomatic and identified on screening colonoscopy. Small (<2 cm) rectal carcinoids may be treated with transanal local excision alone. Rectal tumors >2 cm and all colon carcinoid tumors are treated with standard oncologic colorectal resection. Patients with carcinoid syndrome may be treated with somatostatin analogs for symptomatic control.

Melanoma: Primary and Metastatic

Melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract is most commonly metastatic from a different primary site and occurs in the small intestine. Approximately 15% of melanoma metastatic to the GI tract occurs in the colon (Allen & Cott, 2002; Rengtgen et al., 1984). Primary GI melanoma may occur in the rectum or anus with only case reports of primary colonic melanoma (Avital et al., 2004; Schuchter et al., 2000). Unfortunately, GI melanoma often carries a worse prognosis than does cutaneous melanoma, which many attribute to the later stage at diagnosis. Patients are often asymptomatic but may present with bleeding, obstruction, or pain. The only curative treatment modality is wide surgical excision; however, there is no survival benefit with radical excision with an APR, and therefore, this is reserved for those with intractable pain.

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) can occur anywhere in the GI tract and arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal. They are most commonly diagnosed in men in their fifth or sixth decades of life (Tryggvason et al., 2005). GISTs are slow growing and can grow to a very large size before causing symptoms. Median size at diagnosis for symptomatic patients was found to be 8.9 cm as compared to 2.7 cm in asymptomatic patients (Kingham & DeMatteo, 2009). They occur most commonly in the small intestine and may occur in the rectum, but are rarely present in the colon. These tumors spread hematogenously to the liver or peritoneum, and lymphatic spread is rare. These tumors are unfortunately not responsive to chemotherapy or radiation and are treated with surgical resection alone. A grossly negative margin of 1 cm is recommended in order to obtain a microscopically negative margin. These tumors have a high rate of local recurrence, and therefore all patients should be considered for adjuvant therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, such as imatinib or sunitinib. Recurrence is decreased for rectal GISTs with APR or LAR as compared to wide local excision (Yeh et al., 2000). If the tumor is deemed unresectable, consider neoadjuvant therapy to potentially decrease tumor burden and allow resection in the future.

Sarcoma

Sarcomas may involve the lower intestine either as a primary colorectal sarcoma or as direct extension from a surrounding sarcoma such as a retroperitoneal sarcoma. Primary colorectal sarcomas are rare and are usually of the subtype leiomyosarcoma. As with all sarcomas, tumor grade is the most significant prognostic indicator, and treatment includes radical en bloc resection of all tumor including adjacent structures if able.

Lymphoma

The gastrointestinal tract is the most common site of extranodal lymphoma with colorectal lymphoma accounting for 15% to 20% of GI lymphomas (Koch et al., 2001; Quayle & Lowney, 2006). Due to the increased concentration of lymphatic tissue, approximately 70% of colorectal lymphomas are located in the cecum and ascending colon. Patients most often present in the fifth to seventh decades of life with symptoms of abdominal pain or palpable abdominal mass. Lymphomas, including colorectal lymphoma, are generally considered to be widespread systemic processes and therefore are most often treated with radiation for locoregional control and adjuvant chemotherapy for intermediate or high-grade disease. Surgery may be considered for truly focal disease but is generally reserved for diagnostic purposes or to treat lymphoma-related complications such as perforation, bleeding, and obstruction.

Indications for Stoma Formation for Colorectal Neoplasia

Patients with colorectal tumors may require a stoma that can be categorized as permanent or temporary. Temporary stomas provide diversion of the fecal stream to either decompress proximal to an obstructing mass or protect a distal anastomosis. These are generally loop colostomies or loop ileostomies (Fig. 3-6) depending on the patient’s anatomy, tumor location, and indication for diversion. Patients with obstructing CRC who are not candidates for immediate resection may benefit from a diverting stoma. This allows for continued GI function while the patient completes the workup or undergoes neoadjuvant treatment to reduce tumor burden, or for palliative intent for unresectable and/or metastatic disease.

FIGURE 3-6. Diverting loop ileostomy in a patient with a distal rectal cancer and a low anastomosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Conclusions

Conclusions