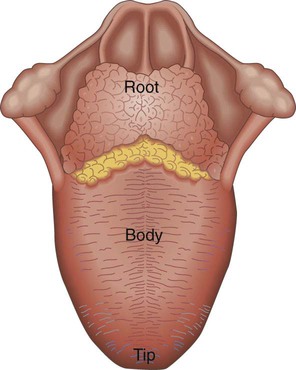

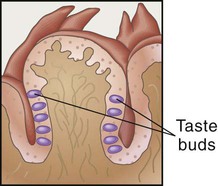

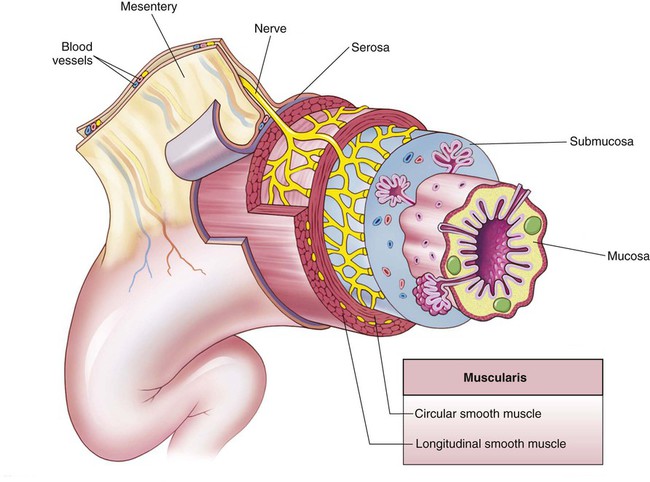

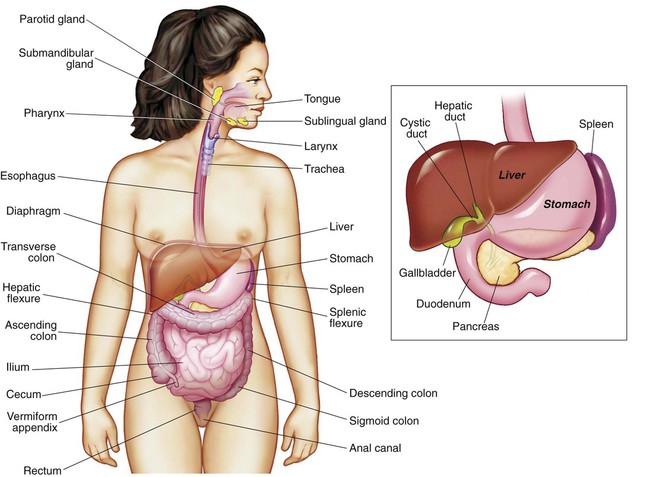

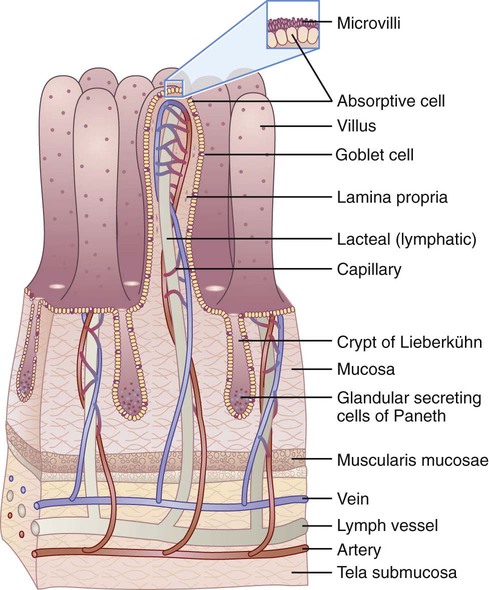

The main organs of the digestion system (Figure 3-1 and Box 3-1) form the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, or alimentary canal, which creates an open tube that runs from the mouth to the anus. Everything we eat is processed through the GI tract. The digestive system consists of a series of organs that prepare ingested nutrients for digestion and absorption and protect against consumed microorganisms and toxic substances. To do this, several processes take place. These processes of ingestion, digestion, absorption, and elimination depend on the motility or movement of the GI wall and the secretions of digestive juices and enzymes.1 Another digestive process that occurs in the mouth is mechanical digestion, which depends on teeth. Teeth rhythmically tear and pulverize food. The enamel covering teeth is the hardest substance in the body and therefore protects teeth from the harsh effects of chewing. The tongue assists with mechanical digestion by guiding food into chewing positions and then leading the pulverized food into the esophagus. Another function of the tongue is that of taste. More than 2000 taste buds are responsible for our sensations of sweet, bitter, sour, and salty when tasting foods (Figure 3-2). Our sense of smell works along with our taste bud sensations. These two combined senses actually account for the perception (and enjoyment) of the flavors of different foods. Our positive or negative response to specific foods based on our sensory perception affects our food choices.2 This mechanical action further breaks down the size of foodstuff and increases exposure to digestive secretions. Muscular actions depend on the four layers of tissues that form the tube of the GI tract (Figure 3-3). The mucosa is composed of mucous membrane and forms the inside layer. Under the mucosa is the submucosa, a layer of connective tissue. Digestion depends on the blood vessels and nerves of the submucosa to regulate digestion. Surrounding the submucosa is a thick layer of muscle tissue called the muscularis. The outermost layer of the GI wall is made of serous membrane called serosa, which is actually the visceral layer of the peritoneum lining the abdominal pelvic cavity, and covers organs.1 Functions of the stomach include the following: • Holding food for partial digestion • Providing muscular action that, combined with gastric juice, mixes and tears food into smaller pieces • Secreting the intrinsic factor for vitamin B12 absorption • Assisting in the destruction, through its acidity of secretions, of pathogenic bacteria that may have inadvertently been consumed1 Gastric secretions occur in three phases: cephalic, gastric, and intestinal.1 The cephalic phase is called the “psychic phase” because mental factors can stimulate gastrin, a hormone secreted by stomach mucosa. In the gastric phase, gastrin increases the release of gastric juices when the stomach is distended by food. The third phase is the intestinal phase in which the gastric secretions change as chyme, a semiliquid mixture of food mass, passes through to the duodenum. Gastric secretions are inhibited by exocrine and nervous reflexes of gastric inhibitory peptides, secretin, and cholecystokinin (CCK) (also called pancreozymin), a hormone secreted by intestinal mucosa. In the small intestine, the nutrients in chyme are prepared for absorption. The small intestine is the major organ of digestion, and the final stages of the digestive process occur here. Because it is also the site of almost all of the absorption of nutrients, the intestinal lining must be able to accommodate the actions of both digestion and absorption. The intestinal walls are covered with a thin layer of mucus, protecting the walls from digestive juices. The walls are also adapted to enhance the absorption process. Finger-like projections called villi greatly increase the amount of mucosal layer available for the absorption of nutrients (Figure 3-4). On the villi are hairlike projections called microvilli that also enhance absorption by their structure and movements. The movement of the food mass through the GI tract is controlled to enhance digestion and absorption. During passage through the GI tract, more than 95% of the carbohydrates, fats, and proteins ingested are absorbed. Some minerals, vitamins, and trace elements may be less absorbed.1 Table 3-1 summarizes the primary mechanisms of the digestive system. Details of carbohydrate, protein, and lipid digestion follow in specific chapters. TABLE 3-1 Data from Thibodeau GA, Patton KT: Anatomy & physiology, ed 5, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.

Digestion, Absorption, and Metabolism

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Digestion

![]() The Mouth

The Mouth

The Esophagus

The Stomach

The Small Intestine

The Large Intestine

MECHANISM

DESCRIPTION

Ingestion

Process of taking food into the mouth, starting it on its journey through the digestive tract

Digestion

A group of processes that break complex nutrients into simpler ones, thus facilitating their absorption; mechanical digestion physically breaks large chunks into small bits; chemical digestion breaks molecules apart

Motility

Movement by the muscular components of the digestive tube, including processes of mechanical digestion; examples include peristalsis and segmentation

Secretion

Release of digestive juices (containing enzymes, acids, bases, mucus, bile, or other products that facilitate digestion); some digestive organs secrete endocrine hormones that regular digestion or metabolism of nutrients

Absorption

Movement of digested nutrients through the GI mucosa and into the internal environment

Elimination

Excretion of the residues of the digestive process (feces) from the rectum, through the anus; defecation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Digestion, Absorption, and Metabolism

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access