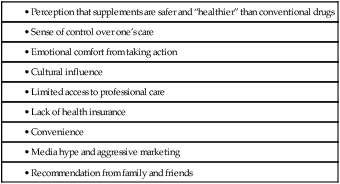

CHAPTER 108 The popularity of supplements may be explained by several factors (Table 108–1). Some people like the sense of empowerment that comes from self-diagnosis and self-prescribing. Others may turn to supplements out of anger or frustration with their healthcare providers. Still others may distrust conventional medicine or may feel it has failed them. In addition, supplements may also be a way to save money: Since these products are available without prescription, they can be purchased without the cost of visiting a prescriber. In fact, according to the NHIS, there is a clear relationship between concern about the costs of conventional care and the likelihood of turning to CAM. However, perhaps the strongest force driving the demand for nutritional supplements is aggressive marketing. A new subscription service—the Natural Medicines Brand Evidence-based Rating (NMBER™) system—offers evidence-based ratings for over 60,000 specific supplement products. Based on scientific evidence of safety and efficacy, each product is assigned a rating between 1 and 10. Products with a low rating are not recommended, whereas those with a high rating are. The NMBER system, created by the publishers of the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, can be accessed online at NMBER.therapeuticresearch.com. There is a fee. Botanical products (medicinal herbs), vitamins, and minerals are regulated under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA)—a bill that exempts these products from meaningful FDA regulation. The DSHEA created a special category for nutritional supplements that exempts them from the scrutiny applied to other foods. The DSHEA also states that products not already sold as drugs can now be sold as dietary supplements. Put another way, if a manufacturer is willing to call its product by another name—“dietary supplement” rather than “drug”—the product can qualify for regulation under the DSHEA, thereby avoiding regulation under the more stringent Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. As discussed in Chapter 3, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act requires that conventional drugs—both prescription and over-the-counter agents—undergo rigorous evaluation of safety and efficacy prior to receiving FDA approval for marketing. The DSHEA imposes no such requirements on “dietary supplements.” That is, dietary supplements can be manufactured and marketed without giving the FDA any proof they are safe or effective. All the manufacturer must do is notify the FDA of efficacy claims. If a product eventually proves harmful or makes false claims, the FDA does have the authority to intervene—but only after the product had been released for marketing. Furthermore, in order to challenge a claim of efficacy, the FDA must file suit in court; the challenge cannot be made through a simple administrative procedure. As you might guess, the DSHEA was created in response to intensive lobbying from the multibillion-dollar dietary supplement industry, which wanted to minimize government oversight. • Helps promote urinary tract health • Helps maintain cardiovascular function • Reduces stress and frustration But labels can’t bear statements or terms like these: • Reduces pain and stiffness of arthritis • Supports the body’s antiviral capabilities • Improves symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease • Relieves menopausal hot flushes • “Antibiotic,” “antiseptic,” “antidepressant,” “laxative,” or “diuretic” • A combination product used to “cleanse the bowel” caused life-threatening heart block. Analysis revealed contamination with Digitalis lanata, a plant with powerful effects on the heart. • Among 125 ephedra products analyzed by the FDA, ephedrine content per dose ranged from undetectable to 110 mg. Also, some products had 6 to 20 additional ingredients. • Testing of 10 brands of ginseng products revealed a 20-fold variation in ginsenoside content. • When the California Department of Health Sciences analyzed 243 Asian patent medicines, they found 24 containing lead, 35 containing mercury, and 36 containing arsenic—all in levels above those permitted in drugs. Seven percent of the products were adulterated with undeclared pharmaceuticals, including ephedrine, chlorpheniramine, methyltestosterone, and phenacetin. This act, passed in 2006, mandates reporting of serious adverse events for nonprescription drugs and dietary supplements. The following events should be reported: deaths, hospitalizations, life-threatening experiences, persistent or significant disabilities, and birth defects. Manufacturers and distributors must report these to the FDA within 15 days. Reports can be filed by telephone or by mail, or through the MEDWATCH program (see Chapter 7). Variability can be reduced through standardization, a three-step process in which the manufacturer (1) prepares an extract of plant parts, (2) analyzes the extract for one or two known active ingredients, and (3) dilutes or concentrates the extract such that the final product contains a predetermined amount of the active ingredient(s). The objective is to achieve therapeutic equivalence from batch to batch made by the same manufacturer, and among batches made by different manufacturers. Table 108–2 lists the concentrations of active ingredients in some standardized preparations. TABLE 108–2 Concentrations of Active Agents in Some Standardized Herbal Preparations A few important interactions have been identified, including the following: • St. John’s wort can induce CYP3A4 (the 3A4 isozyme of cytochrome P450), and can thereby accelerate the metabolism of many drugs, causing a loss of therapeutic effects. • Several herbal products, including Ginkgo biloba, feverfew, and garlic, suppress platelet aggregation, and hence can increase the risk of bleeding in patients receiving antiplatelet drugs (eg, aspirin) or anticoagulants (eg, warfarin, heparin). • Ma huang (ephedra) contains ephedrine, a compound that can elevate blood pressure and stimulate the heart and central nervous system (CNS). Accordingly, ephedra can intensify the effects of pressor agents, cardiac stimulants, and CNS stimulants, and counteract the beneficial effects of antihypertensive drugs and CNS depressants.

Dietary supplements

Regulation of dietary supplements

Dietary supplement health and education ACT of 1994

Core provisions

Package labeling

Impurities, adulterants, and variability

Dietary supplement and nonprescription drug consumer protection ACT

Standardization of herbal products

Herb

Amount of Active Agent

Black cohosh

2.5% Triterpene glycosides

Echinacea

4% Phenolic compounds

Feverfew

0.2% Parthenolide

Ginkgo biloba

24% Ginkgo flavenoids, 6% terpenoids

St. John’s wort

0.3% Hypericin

Valerian root

1% Valerianic acid

Adverse interactions with conventional drugs

Some commonly used dietary supplements

Black cohosh

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Dietary supplements

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access