ICD-10 Diagnostic Coding

Janet Beik

Learning Objectives

1. Identify the meaning of a diagnosis and state where it can be found in a patient record.

2. Discuss the history and development of diagnostic coding.

3. Describe the process of classifying diseases.

5. List the coding steps for the Alphabetic Index.

6. Explain the format and structure of codes and conventions in the ICD-10-CM Tabular List.

7. Outline the official guidelines for diagnostic coding and reporting.

8. Describe other coding features in the ICD-10-CM.

9. Document the coding steps for the Tabular List.

11. Discuss General Equivalency Mappings (GEMs).

Vocabulary

7th character

adverse effects

category

code

code set

combination code

conventions

default code

diagnosis

eponym

essential modifiers

etiology

first-listed diagnosis

General Equivalency Mappings (GEMs)

histology

in situ

laterality

main term

manifestation

morphology

neoplasm

NEC (not elsewhere classifiable)

nonessential modifiers

NOS (not otherwise specified)

Notes

placeholder character “x”

principal diagnosis

sequela (pl. sequelae)

subcategory

underdosing

Scenario

When Park Chalmers was a little boy, he had wanted to be a doctor; however, when he fainted after witnessing a bicycle accident that severely injured his best friend’s arm, Park realized that the clinical side of medicine was not for him. Still, the field of medicine intrigued him. After high school, Park moved from one dead-end job to another. He soon faced the fact that without specialized career training, his prospects for living comfortably in an apartment of his own were dim.

In his search for more meaningful employment, Park noticed an advertisement in the classified section of the newspaper for a coder at a local medical clinic. The position required course work or on-the-job experience in ICD and CPT coding. The pay range noted in the ad was enticing to Park; however, he had no idea what ICD or CPT coding was. The terms themselves were “codes” to Park.

Curious about the meaning of ICD and CPT coding, Park made inquiries when he attended a job fair at the community college. He was directed to the health careers booth, where current health insurance students, with the aid of an instructor, answered all his questions and gave a brief demonstration on diagnostic coding.

“I think I can learn this coding stuff,” Park said to himself, and he headed for the Student Services Department to enroll in the upcoming health insurance program.

Introduction to the International Classification of Diseases Coding System

In the healthcare profession, there is a recognized process for transforming written descriptions of a patient’s disease process, disorder, or injury into universal numeric or alphanumeric formats (i.e., codes) that are understood by all healthcare entities, including providers, government health programs, private health insurance companies, and workers’ compensation carriers. In very basic language, a diagnosis is the reason that brought the patient to the healthcare facility, such as a rash, sore throat, or chest pains. A final diagnosis, after examination, can be a much more precise statement.

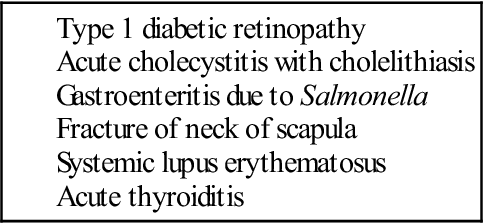

The diagnosis can be taken from a variety of sources in the medical record, such as the clinical notes, laboratory tests, radiologic results, and other sources. The diagnosis must be determined by the healthcare professional providing the medical care. Table 1 lists examples of medical diagnoses.

When the healthcare insurance professional generates an insurance claim for payment of the provider’s services, the written diagnosis itself does not appear on the claim—only the code appears. It is very important that the code describes the diagnosis accurately and to the greatest specificity, to obtain maximum reimbursement for the provider and patient, and that the diagnosis justifies the medical necessity of the procedure codes documented on the insurance claim.

Two Major Coding Structures

The U.S. healthcare system currently uses two major coding structures: the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis and (inpatient) procedure codes, and the Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition (CPT-4) procedure codes.

ICD-10 codes are divided into two systems. The ICD-10-CM (clinical modification) codes are used in physicians’ offices and outpatient settings for the coding of diseases and the signs, symptoms, abnormal findings, complaints, social circumstances, and external causes of injury or diseases, as classified by the World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10-PCS (procedure coding system) is used in the inpatient hospital setting for reporting inpatient procedures only; it helps establish the diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) that most third-party payers use to determine payment for related services and procedures.

CPT-4 codes are used to determine third-party payment for related physician services and procedures for reimbursement purposes. These codes also help establish the ambulatory payment classifications (APCs) used by most providers for related services and procedures in the outpatient setting.

This chapter provides the basics of ICD-10-CM diagnostic coding. After reading this chapter, students should have a working knowledge of the ICD-10-CM system and the ability to generate valid codes for simple diagnoses.

History and Development of the ICD Coding System

The history of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system dates back to the late nineteenth century in Europe, when it was determined that there was a need for the standardization of medical concepts and terminology. The ICD system was the product of a group effort involving WHO and 10 international centers. Using this system, medical terms reported on death certificates by physicians, medical examiners, and coroners could be grouped together for statistical purposes. The purpose of the system was to promote a means of comparing the collection, classification, processing, and presentation of mortality (death) statistics.

The first ICD system (ICD-1) was put into use in 1900. Since then the ICD has been modified approximately every 10 years, with the exception of the 20-year period between the past two revisions, ICD-9 and ICD-10. The rationale for these periodic revisions has been to reflect advances in medical science and changes in diagnostic terminology. In 1999, the United States replaced ICD-9 with ICD-10 for coding on death certificates; however, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) did not publish the final rule for full adoption of the ICD-10 in the United States until January, 2009. Until that time, the United States was one of the few countries that was not using ICD-10. As of this writing, the compliance date for implementation of the ICD-10 coding system is October 1, 2014, for all covered entities. Students should visit the Web site http://cms.gov/icd10/ periodically to keep abreast of further information or extension of this compliance date.

Uses of Coded Data

Coding of healthcare data allows access to health records according to diagnoses and procedures for use in clinical care, research, and education. Following is a list of other common uses of codes in healthcare:

• Measuring the quality, safety, and effectiveness of care

• Designing payment systems and processing claims for reimbursement

• Conducting research, epidemiologic studies, and clinical trials

• Facilitating operational and strategic planning and the designing of healthcare delivery systems

• Improving clinical, financial, and administrative performance

• Preventing and detecting healthcare fraud and abuse

• Tracking public concerns and assessing the risks of adverse public health events

Why the Change to ICD-10-CM?

After using ICD-9 for 20 years, one may wonder why the change to ICD-10. In many ways, the ICD-10-CM is comparable to the former ICD-9-CM. The guidelines, conventions, and rules and the organization of the codes are very similar. However, many improvements have been made to coding in the ICD-10-CM. For example, a single code can report a disease and its current manifestation (signs or symptoms of a disease). In fracture care, the code differentiates various outcomes with mandatory use of the appropriate 7th character (in parentheses):

• an initial encounter for fracture (A)

• a subsequent encounter for fracture with routine healing (D)

• a subsequent encounter for fracture with delayed healing (G)

• a subsequent encounter for fracture with nonunion (K)

• a subsequent encounter for fracture with malunion (P)

Similarly, the trimester is designated in obstetric codes. The episode of care codes (delivery, antepartum, postpartum) have a final character identifying the trimester of pregnancy in which the condition occurred. Because certain obstetric conditions or complications occur during certain trimesters, not all conditions include codes for all three trimesters. For example, preterm labor without delivery can occur in either the second or third trimester only; therefore, the subcategory O60.0 (Preterm labor without delivery) is further subdivided as

• Preterm labor without delivery, unspecified trimester—O60.00

• Preterm labor without delivery, second trimester—O60.02

If preterm labor with preterm delivery occurred (subcategory O60.1), a 7th character would be assigned. For example: the 7th character “0” is used for single gestation and multiple gestations in which the fetus is unspecified. Characters 1 through 5 are used for cases of multiple gestations to identify the fetus for which the code applies. Seventh character “9” identifies “other fetus.”

Additional documentation is required when a claim is submitted to explain that the injury or condition treated the second time is different from the one that was treated previously.

The number of codes in the ICD-10-CM has increased significantly compared with the number in the ICD-9-CM; ICD-9 has 13,600 codes, whereas ICD-10 has nearly 70,000. Some of this growth is due to laterality (i.e., the side of the body on which surgery was performed or the side of the body affected by the condition). For example, an ICD-9-CM code may identify simply a condition of an ovary; the ICD-10-CM system has four identifying codes: unspecified ovary, right ovary, left ovary, or bilateral (both sides) condition of the ovary(ies). In the ICD-10 diagnosis code set, characters within the code identify right versus left, initial encounter versus subsequent encounter, and other more precise clinical information.

Another issue with ICD-9 is that it was running out of available code numbers in some chapters. ICD-10 codes have more characters, which greatly expands the number of codes available for use. With more available codes, it is less likely that chapters will run out of codes in the future. Another issue addressed in ICD-10 is the use of full code titles, reflecting advances in medical knowledge and technology. Additionally, diagnosis coding under the ICD-10-CM uses 3 to 7 digits, rather than the 3 to 5 digits used in ICD-9-CM; however, the formats of the code sets are similar. Table 2 provides a comparison of the features of the ICD-9 and ICD-10 code sets.

TABLE 2

Comparisons of the Diagnosis Code Sets

| ICD-9 | ICD-10 |

| 3-5 characters in length | 3-7 characters in length |

| Approximately 13,000 codes | Approximately 68,000 available codes |

| First digit may be alpha (E or V) or numeric; digits 2-5 are numeric | Digit 1 is alpha; digits 2 and 3 are numeric; digits 4-7 are alpha or numeric |

| Limited space for adding new codes | Flexible for adding new codes |

| Lacks detail | Very specific |

| Lacks laterality | Has laterality (codes identifying right and left) |

ICD-10-CM Coding and Reporting Guidelines

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), two departments of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), have provided guidelines for coding and reporting using the ICD-10-CM coding systems (these guidelines are summarized later in the chapter). Guidelines for diagnostic coding also can be found on the Websites of these two government entities. These guidelines should be used as a companion document to the official version published by the U.S. Government Printing Office. The CMS Website (http://www.cms.gov/) has extensive information and guidelines for the ICD-10 system. To access relevant information, type “ICD-10” in the CMS home page search box.

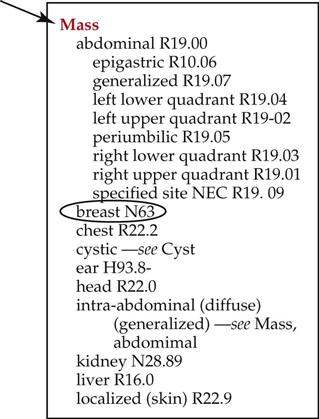

Process of Classifying Diseases

The first thing the coder must do in the coding process is locate the diagnosis in the patient’s medical record. This task can be straightforward sometimes, because many encounter forms (also known as superbills) list the more frequently used diagnoses in a certain medical specialty, along with their corresponding diagnosis codes (Figure 1). Other times, the coder may have to refer to the clinical notes in the patient’s record to locate the diagnosis. If the notes are handwritten, deciphering the healthcare professional’s handwriting sometimes can be challenging. With practice and experience, locating the diagnosis in the clinical notes and translating a physician’s handwriting become easier.

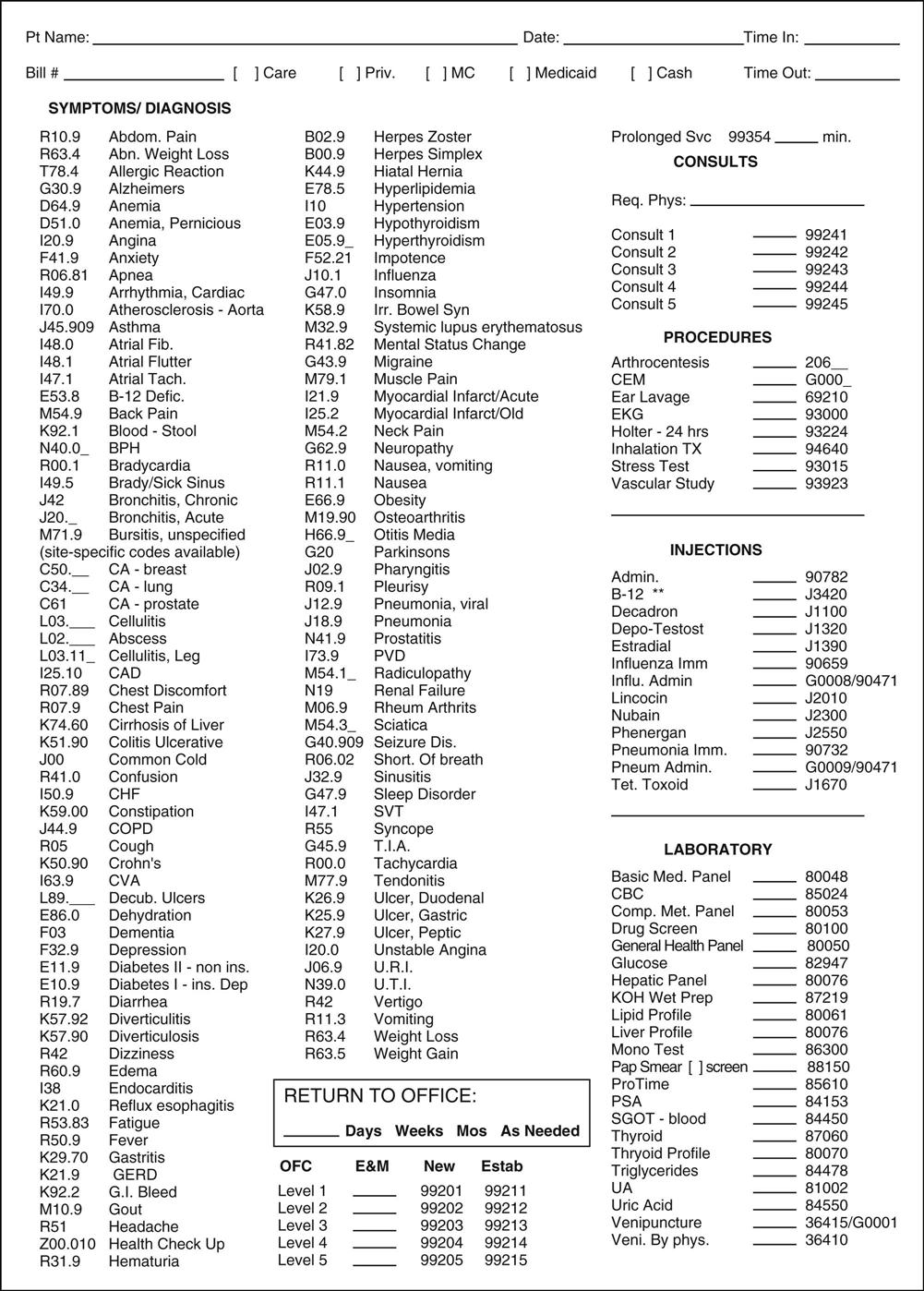

After the diagnosis has been determined, the main term (sometimes referred to as the lead term) in the diagnosis should be identified. For example, if the diagnosis is “breast mass,” the main term is “mass.” (The anatomic site [e.g., “breast”] is not used in the Alphabetic Index to Diseases.) Figure 2 illustrates how the main term “mass” appears in the Index.

ICD-10-CM Code Structure

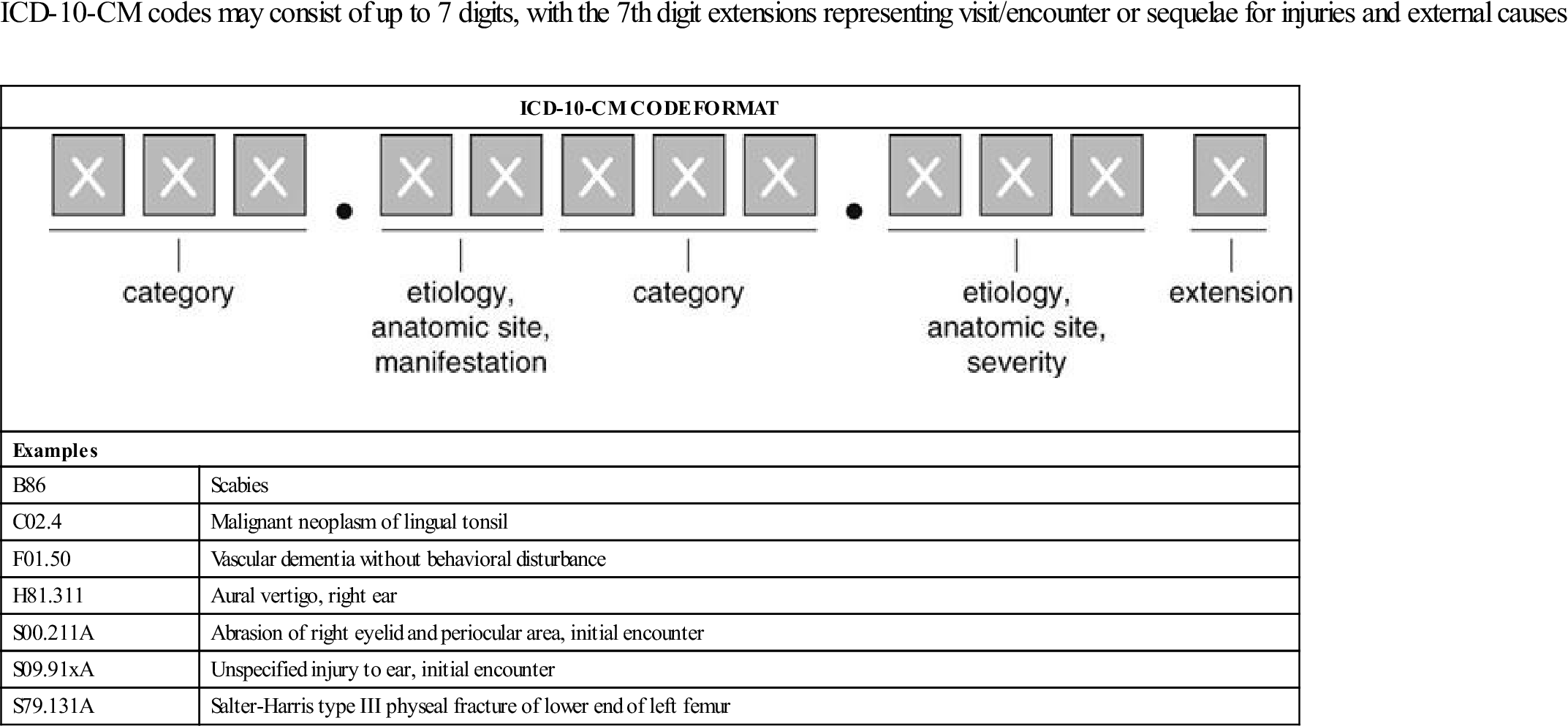

As mentioned, an ICD-10-CM code has 3 to 7 characters (Table 3). The first character of an ICD-10-CM code is always an alphabetic letter, and all letters of the alphabet are used in ICD-10-CM coding except the letter U. Alphabetic characters are not case sensitive.

TABLE 3

Code Structure of the ICD-10-CM

| ICD-10-CM codes may consist of up to 7 digits, with the 7th digit extensions representing visit/encounter or sequelae for injuries and external causes |

| ICD-10-CM CODE FORMAT | |

| |

| Examples | |

| B86 | Scabies |

| C02.4 | Malignant neoplasm of lingual tonsil |

| F01.50 | Vascular dementia without behavioral disturbance |

| H81.311 | Aural vertigo, right ear |

| S00.211A | Abrasion of right eyelid and periocular area, initial encounter |

| S09.91xA | Unspecified injury to ear, initial encounter |

| S79.131A | Salter-Harris type III physeal fracture of lower end of left femur |

Codes longer than 3 digits always have a decimal point after the first 3 characters. Each additional character adds more specificity to the disease or condition. The additional characters add to the clinical detail and address information about previously classified diseases or conditions discovered since the last edition.

Format of the ICD-10-CM Manual

Before any attempt is made to code a diagnosis, the coder must become familiar with the contents and structure of the coding manual. The format of the ICD-10-CM manual may differ among publishers in how the material is arranged in the introduction or preface; however, the basic information is the same. The prefacing instructions used in this chapter follow those in the text 2013 ICD-10-CM Draft Edition, by Carol J. Buck, published by Saunders (2013). The information, coding instructions, and codes were current at the time of this writing. To keep up-to-date on ICD-10-CM coding practices, the coder should always consult the most recently published ICD-10-CM coding manual.

Note: The link for the complete ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting is listed in the section Websites to Explore at the end of this chapter.

The first several pages of the ICD-10-CM manual contain the following:

• Part I—Introduction (containing ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting)

• Index to Diseases and Injuries

• Table of Drugs and Chemicals

• External Cause of Injuries Index

• Part III—Tabular List of Diseases and Injuries (21 chapters [Table 4]).

TABLE 4

| Chapter 1 (A00-B99) | Certain Infectious and Parasitic Diseases |

| Chapter 2 (C00-D48) | Neoplasms |

| Chapter 3 (D50-D89) | Diseases of the Blood and Blood-forming Organs and Certain Disorders Involving the Immune Mechanism |

| Chapter 4 (E00-E90) | Endocrine, Nutritional, and Metabolic Diseases |

| Chapter 5 (F01-F99) | Mental and Behavioral Disorders |

| Chapter 6 (G00-G99) | Diseases of the Nervous System |

| Chapter 7 (H00-H59) | Diseases of the Eye and Adnexa |

| Chapter 8 (H60-H95) | Diseases of the Ear and Mastoid Process |

| Chapter 9 (I00-I97) | Diseases of the Circulatory System |

| Chapter 10 (J00-J99) | Diseases of the Respiratory System |

| Chapter 11 (K00-K93) | Diseases of the Digestive System |

| Chapter 12 (L00-L99) | Diseases of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue |

| Chapter 13 (M00-M99) | Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue |

| Chapter 14 (N00-N99) | Diseases of the Genitourinary System |

| Chapter 15 (O00-O9A.53) | Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Puerperium |

| Chapter 16 (P04-P94) | Certain Conditions Originating in the Perinatal Period |

| Chapter 17 (Q00-Q94) | Congenital Malformations, Deformations, and Chromosomal Abnormalities |

| Chapter 18 (R00-R99) | Symptoms, Signs, and Abnormal Clinical and Laboratory Findings, Not Elsewhere Classified |

| Chapter 19 (S00-T98) | Injury, Poisoning, and Certain Other Consequences of External Causes |

| Chapter 20 (V01-Y97) | External Causes of Morbidity |

| Chapter 21 (Z00-Z99-) | Factors Influencing Health Status and Contact with Health Services |

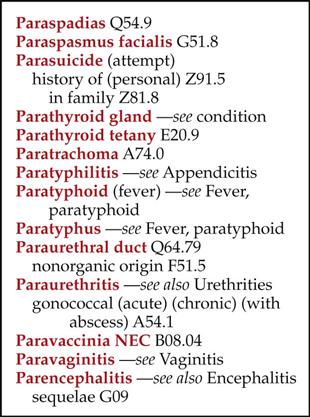

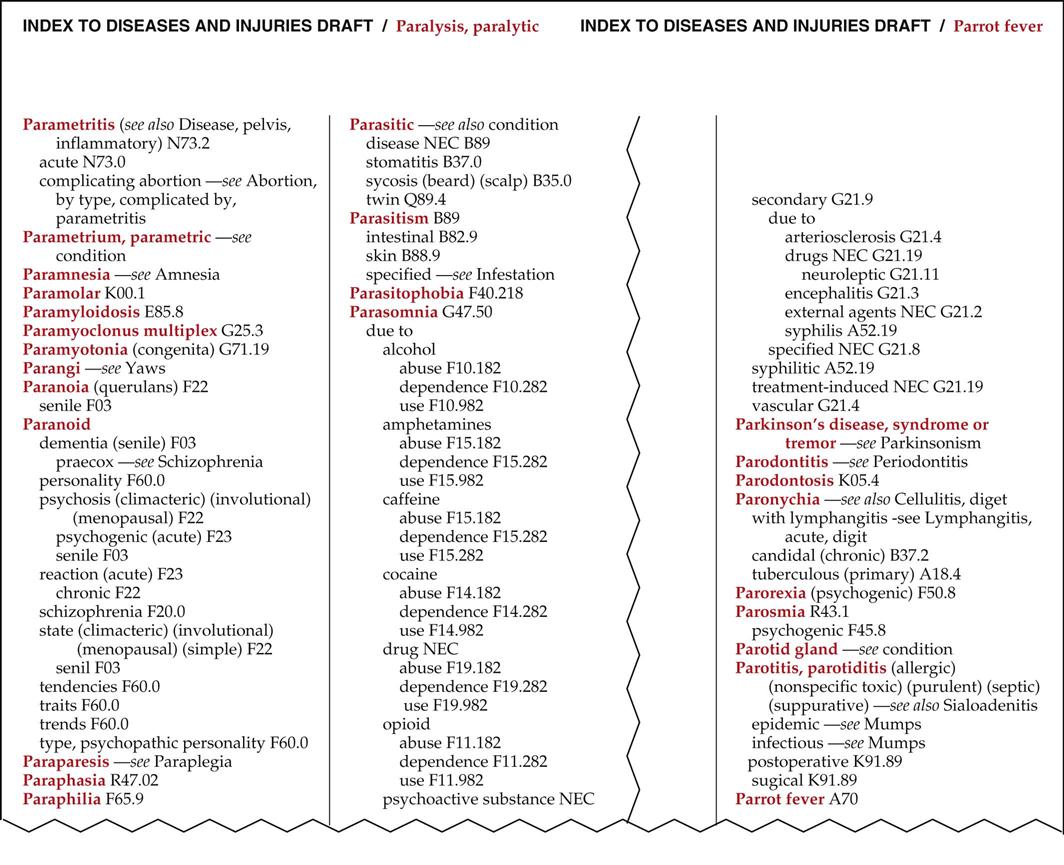

Alphabetic Index

The first main section of the manual is Part II, the Alphabetic Index (hereafter referred to as the Index), which contains a list of terms arranged alphabetically, along with their corresponding codes (Figure 3). Each page of the Index is divided into three columns. At the extreme top right (or left) corner of each page is a guide word, similar to guide words on each page of a dictionary, to assist the coder in locating the appropriate page (Figure 4). For example, Figure 5 shows the location of the main term “Paranoid” in 2013 ICD-10-CM Draft Edition by Buck. The guide words on the left-hand page are “Paralysis, paralytic,” and the guide word on the right-hand page is “Parrot fever”; therefore, the coder knows that the main term, “Paranoid,” is located alphabetically within these two pages. Note that “Paranoid” is presented in bold-face type (red bold-face type in Buck, black bold-face type in other coding manuals). This indicates a main term.

Main Terms.

As mentioned, the first step in diagnostic coding is to identify the main term of the diagnostic statement. This term can typically be found in the diagnostic statement in the patient’s medical record. After the main term has been identified, it should be located in the Index. Main terms are generally not organized by anatomic site. When locating an anatomic term, such as “shoulder,” the Index says, “see condition.” Main terms typically include:

• a disease (bronchitis or influenza)

• a condition (fracture, fatigue, or injury)

• an adjective (double, large, or kinked)

• a noun (a disease, disturbance, or syndrome)

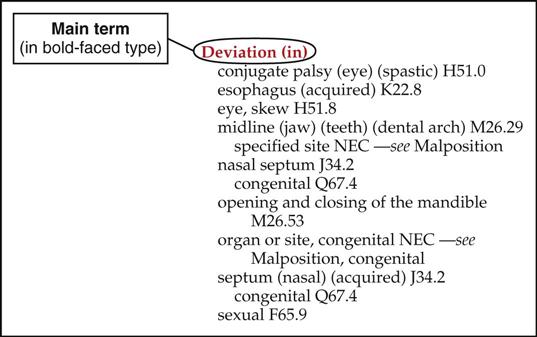

If a patient has a diagnosis of deviated nasal septum, the main term is “deviated,” which is found in the Index under “deviation.” Remember, main terms in the Index are printed in bold black type (bold red type in Buck) to assist the coder in locating the desired disease or condition (Figure 6).

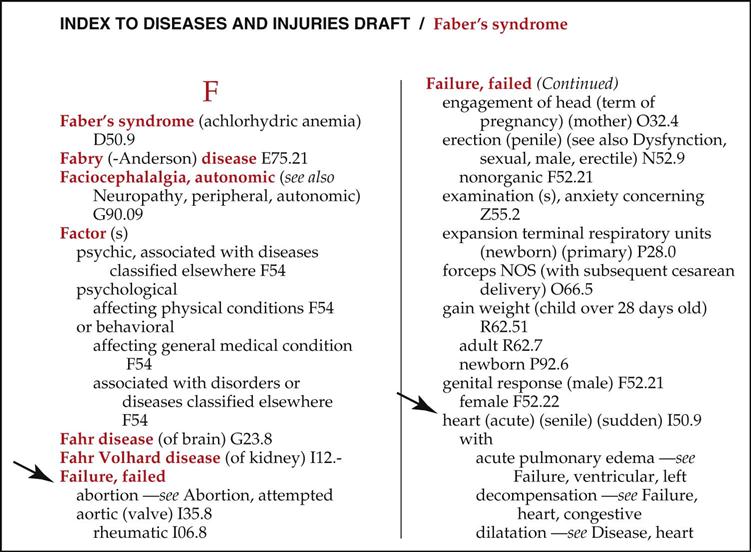

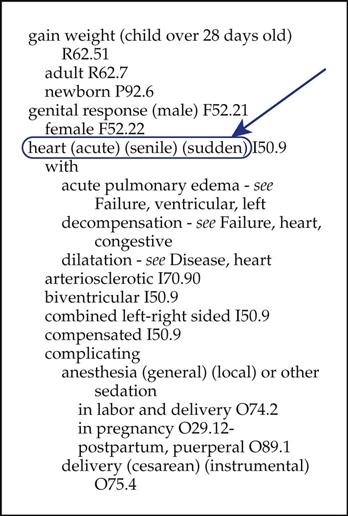

For clarification, let’s walk through this process with a patient whose diagnosis has been identified as “congestive heart failure.” “Heart” is an anatomic site. If you locate it in the Index, the entry will say, “see condition.” So, we find “congestive” in the Index, and following alphabetically down to “heart,” we see the cross-reference “see failure—heart, congestive.” We now know that “failure” is the correct main term, so we locate “failure” in the Index (Figure 7). Let’s look at another example. You locate the diagnosis “breast mass” in Evelyn Hake’s medical record. Remember, anatomic sites are not main terms; therefore, “breast” cannot be the main term. This means that the main term is “mass.” Locating “mass” in the Index and moving down alphabetically, you locate “breast,” followed by the partial code N63. Locating this partial code in the Index is just the first step. The cardinal rule of coding is never to code from the Index alone. Before a final code is assigned, it is important that the coder read any special notes or instructions; he or she then turns to the Tabular List (hereafter referred to as the Tabular), to locate the code that defines the diagnosis to the greatest specificity. However, before we explore the Tabular, we have much more to learn about the Alphabetic Index.

Essential and Nonessential Modifiers.

Any relevant subterms or essential modifiers are indented under the main terms. Indented subterms are always used in combination with the main term. They describe different sites, the etiology (cause or origin of a disease or condition), and clinical types. Essential modifiers must be a part of the documented diagnosis (Figure 8).

Frequently, a main term is immediately followed by an additional word or words in parentheses, or nonessential modifiers. Nonessential modifiers that appear in parentheses do not affect the code number assigned but are provided to assist the coder in locating the correct code (Figure 9).

In our earlier example diagnosis of heart failure (see Figures 7 and 9), note the nonessential modifiers in parentheses immediately after “heart”—(acute) (senile) (sudden). These subterms do not affect the diagnostic code assigned and are given to assist the coder in locating the correct code. They may or may not be a part of the documented diagnosis. Also note that the 4-character code I50.9 follows the parenthetical nonessential modifiers. If no other words appear in the stated diagnosis in the patient record, the next step is to cross-reference the code to the Tabular—the section containing diagnosis codes arranged alphanumerically and divided into chapters based on body system (anatomic site) or condition (etiology)—to finalize the process of assigning the correct code. Further steps in locating the correct code in the Tabular are discussed later in this chapter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree