Diagnostic Coding

Chapter objectives

After completion of this chapter, the student should be able to

1. Discuss the meaning of a diagnosis and where it can be found in a patient record.

2. Name the three major coding structures and state the purpose of each.

3. Discuss the history and development of diagnostic coding.

4. Provide a brief comparison of the two diagnostic coding systems.

6. Describe the process of classifying diseases.

7. Explain the format and structure of ICD-9-CM codes in the Tabular List.

8. Define and provide examples for symbols and conventions used in ICD-9-CM Volume 1.

9. List the essential steps to diagnostic coding.

10. Identify and explain special coding situations.

12. Outline the coding steps for the Alphabetic Index in ICD-10-CM.

13. Explain the format and structure of codes and conventions in ICD-10-CM Tabular List.

14. Discuss ICD-10-CM general coding guidelines and chapter-specific guidelines.

15. State important diagnostic coding and reporting guidelines for outpatient services in ICD-10-CM.

17. Display an understanding of the importance of learning both diagnostic coding systems.

Chapter terms

category

code set

combination code

contraindication

conventions

default code

diagnosis

E codes

eponyms

essential modifiers

etiology

first-listed diagnosis

laterality

Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs)

main term

manifestation

morphology

National Coverage Determinations (NCDs)

neoplasm

NEC (“not elsewhere classifiable”)

nonessential modifiers

NOS (“not otherwise specified”)

notes

placeholder character

principal diagnosis

sequela (pl. sequelae)

7th character

subcategory

subclassification

V codes

Introduction to international classification of diseases coding system

In the healthcare profession, there is a recognized process of transforming descriptions of a patient’s disease process, disorder, or injury into universal numerical or alphanumerical formats—codes—that are understood by all healthcare entities, including providers, government health programs, private health insurance companies, and workers’ compensation carriers. In very basic language, a diagnosis is the reason that brought the patient to the healthcare facility, such as a rash, sore throat, or chest pains. A final diagnosis after examination can be a much more precise statement.

The diagnosis can be taken from a variety of sources within the medical record, such as the clinical notes, laboratory tests, radiological results, and other sources. The diagnosis must be determined by the healthcare professional providing the medical care. Table 12-1 lists examples of medical diagnoses.

Table 12-1

Diaper dermatitis

Streptococcal sore throat

Intercostal chest pain

Fracture of neck of scapula

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Acute thyroiditis

When the healthcare insurance professional generates an insurance claim for payment of the provider’s services, the diagnosis itself does not appear on the claim—only the code appears. It is very important that the code describes the diagnosis accurately and to the greatest specificity to receive maximum reimbursement for the provider and patient and that the diagnosis justifies the medical necessity of the procedure codes documented on the insurance claim.

Three Major Coding Structures

The U.S. healthcare system currently uses three major coding structures. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes (Volumes 1 and 2) and ICD-9-CM procedure codes (Volume 3). ICD-9-CM Volumes 1 and 2 are used to code diagnoses in physicians’ offices and outpatient settings along with Current Procedural Terminology, 4th revision (CPT-4) codes to determine third-party payment for related services and procedures for reimbursement purposes. These codes also help establish the ambulatory payment classifications (APCs) used by most providers for related services and procedures in the outpatient setting. The procedure codes in Volume 3 establish diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) that most third-party payers use to determine payment for related services and procedures in an inpatient hospital setting. (DRGs and APCs are discussed in detail in Chapter 17.)

This chapter provides the basics of diagnostic coding. After completing the assigned readings and exercises, students should have a working knowledge of both the ICD-9-CM and the ICD-10-CM systems with the ability to generate valid codes for simple diagnoses. Students who wish to pursue a career in coding and become certified should explore the opportunities available in local coding programs or online.  Visit the Evolve site for more information on becoming certified in coding.

Visit the Evolve site for more information on becoming certified in coding.

History of international classification of diseases coding

The history of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system dates back to the late 19th century in Europe when it was determined that there was a need for the standardization of medical concepts and terminology. The ICD system resulted from a group effort between the World Health Organization and 10 international centers so that medical terms reported on death certificates by physicians, medical examiners, and coroners could be grouped together for statistical purposes. The purpose of this system was to promote a way of comparing the collection, classification, processing, and presentation of mortality (death) statistics.

The first ICD system (ICD-1) was put into use in 1900. Since then, the ICD has been modified approximately once every 10 years with the exception of the 20-year period between the last two revisions—ICD-9 and ICD-10 (Table 12-2). The rationale for these periodic revisions has been to reflect advances in medical science and changes in diagnostic terminology. In 1999, the United States replaced ICD-9 with ICD-10 for coding on death certificates; however, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) did not publish the final rule for full adoption of the ICD-10 in the United States until January 2009. Until that time, the United States was one of the few countries that was not using ICD-10.  Visit the Evolve site to read the HHS Final Rule for ICD-10 and to find more information on the history and development of the ICD coding system.

Visit the Evolve site to read the HHS Final Rule for ICD-10 and to find more information on the history and development of the ICD coding system.

Table 12-2

International Classification of Diseases Implementation in the United States

| Designation | Years in Effect |

| ICD-1 | 1900-1909 |

| ICD-2 | 1910-1920 |

| ICD-3 | 1921-1929 |

| ICD-4 | 1930-1938 |

| ICD-5 | 1939-1948 |

| ICD-6 | 1949-1957 |

| ICD-7 | 1958-1967 |

| ICD-8* | 1968-1978 |

| ICD-9 | 1979-2013 |

| ICD-10 | 1999 (death certificates only); 2013 |

*The United States generally accepted the World Health Organization revisions except for the 8th Revision; the United States disagreed with some parts of the classification system, specifically some categories in the diseases of the circulatory system. As a result, the United States produced its own version of the ICD, referred to as ICDA-8.

The compliance date for implementation of the ICD-10 coding system is (as of this writing) October 1, 2014, for all covered entities. Students should visit http://cms.gov/icd10/ periodically to keep abreast of further changes to this compliance date.

Uses of Coded Data

Coding of healthcare data allows access to health records according to diagnoses and procedures for use in clinical care, research, and education. Following is a list of other common uses of codes in healthcare:

• Measuring the quality, safety, and effectiveness of care

• Designing payment systems and processing claims for reimbursement

• Conducting research, epidemiological studies, and clinical trials

• Operational and strategic planning and designing healthcare delivery systems

• Improving clinical, financial, and administrative performance

• Preventing and detecting healthcare fraud and abuse

• Tracking public concerns and assessing risks of adverse public health events

Two diagnostic coding systems

In this chapter, we look at two different diagnostic coding systems: ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM. After a comparison of the two systems and a brief discussion of the history of diagnostic coding, the ICD-9 system is presented followed by ICD-10. The reason both systems are discussed is because ICD-9 is still being used, and the health insurance professional needs to know how to use it until the transition to ICD-10.

Comparing the Two Systems

As mentioned previously, a primary concern with the current ICD-9 system is the lack of specificity of the information expressed in the codes. For example, if a patient is seen for treatment of an injury to the left leg, the ICD-9 diagnosis code does not distinguish left or right leg. If the patient is seen a few weeks later for another injury, this time on the right leg, the same ICD-9 diagnosis code would be reported. Additional documentation would likely be required when a claim is submitted to explain that the injury treated the second time is different from the one that was treated previously. In the ICD-10 diagnosis code set, characters within the code identify right versus left, initial encounter versus subsequent encounter, and other clinical information.

Another issue with ICD-9 is that it is running out of available code numbers in some chapters. ICD-10 codes have increased character length, which greatly expands the number of codes that are available for use. With more available codes, it is less likely that chapters will run out of codes in the future. Other issues that are addressed in ICD-10 include the use of full code titles, reflecting advances in medical knowledge and technology. Additionally, diagnosis coding under ICD-10-CM uses 3 to 7 digits instead of the 3 to 5 digits used with ICD-9-CM, but the format of the code sets is similar. Table 12-3 provides a comparison of the features of the ICD-9 and ICD-10 code sets.

Table 12-3

Comparisons of the Diagnosis Code Sets

| ICD-9 | ICD-10 |

| 3-5 characters in length | 3-7 characters in length |

| Approximately 13,000 codes | Approximately 68,000 available codes |

| First digit may be alpha (E or V) or numeric; digits 2-5 are numeric | Digit 1 is alpha; digits 2 and 3 are numeric; digits 4-7 are alpha or numeric |

| Limited space for adding new codes | Flexible for adding new codes |

| Lacks detail | Very specific |

| Lacks laterality | Has laterality (codes identifying right and left) |

Examples in Table 12-4 provide a comparison of the formats of the ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes. Note the use of alpha characters and longer codes in ICD-10. In contrast to ICD-9, the alpha characters in ICD-10 are not case sensitive.

Table 12-4

Comparison of Formats of ICD-9 and ICD-10 Code Sets

| ICD-9 Diagnosis Code | ICD-10 Diagnosis Code |

| 382.9 Acute otitis media | B01.2 Varicella pneumonia |

| 540.9 Acute appendicitis | K21.0 Gastro-esophageal reflux disease with esophagitis |

| 780.01 Coma | O30.003 Twin pregnancy, unspecified, third trimester |

From American Medical Association, 2010. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/399/icd10-icd9-differences-fact-sheet.pdf

Guidelines

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), two departments within HHS, provide guidelines for coding and reporting using the ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM coding systems. Guidelines for both diagnostic coding systems can be found on the websites of these two government entities. These guidelines should be used as a companion document to the official version as published by the U.S. Government Printing Office. To view these guidelines, enter “ICD-9 Guidelines” in the search box on CDC website (www.cdc.gov/). The CMS website (http://www.cms.gov/) has extensive information and guidelines for the new ICD-10 system. To access relevant information on ICD-10, type “ICD-10” in the CMS home page search box.

ICD-9-CM coding manual

The ICD-9-CM currently consists of three volumes:

• Volume 2 is the Alphabetic Index listing all diagnoses alphabetically by their basic description.

• Volume 3 contains Procedure Codes used for hospital inpatient procedure coding.

Although all three volumes are available in a single book, most publishers combine Volumes 1 and 2 in a separate manual. Typically, insurance companies do not require the use of Volume 3 for physician and outpatient billing; however, Volume 3 is still used for hospital inpatient coding. Medicare Part B (physician services) does not accept codes from Volume 3; if they are used, the claim is denied. It is important that the health insurance professional obtain and use the most recent version of the ICD-9-CM for effective and accurate coding. Any questions regarding which volume to use on an insurance claim should be addressed to the appropriate carrier, fiscal intermediary, or billing consultant.

Before any attempt is made to code a diagnosis, the health insurance professional must become familiar with the contents and structure of the ICD-9 manual. The format of the ICD-9 differs among publishers regarding how the material is arranged; however, the basic information is the same. The prefacing instructions given here are from the 2012 ICD-9-CM, Volumes 1, 2, & 3, Professional Edition by Carol J. Buck, published by Saunders, which was current at the time of this writing.

Although the ICD-9-CM manual used as reference in this chapter contains all three volumes, we discuss only Volumes 1 and 2, which deal with diagnostic coding in all healthcare settings, in this chapter. Volume 3, used for inpatient hospital procedural coding, is addressed briefly in Chapter 18.

The contents of the Buck 2012 ICD-9-CM manual discussed in this chapter are as follows:

• Guide to Using the 2012 ICD-9-CM

• Guide to the 2012 ICD-9-CM Updates

• Part II, Alphabetic Index Volume 2

• Section I, Index to Diseases and Injuries

• Section II, Table of Drugs and Chemicals

• Section III, Index to External Causes of Injury (E-Codes)

• Part III, Diseases: Tabular List Volume 1

• Infectious and Parasitic Diseases

• Endocrine, Nutritional, and Metabolic Diseases and Immunity Disorders

• Diseases of the Blood and Blood-Forming Organs

• Mental, Behavioral, and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

• Diseases of the Nervous System and Sense Organs

• Diseases of the Circulatory System

• Diseases of the Respiratory System

• Diseases of the Digestive System

• Diseases of the Genitourinary System

• Complications of Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Puerperium

• Diseases of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

• Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue

• Certain Conditions Originating in the Perinatal Period

• Symptoms, Signs, and Ill-Defined Conditions

• Supplementary Classification of External Causes of Injury and Poisoning (E-Codes)

• Appendix A, Morphology of Neoplasms

• Appendix B, Glossary of Mental Disorders (deleted as of October 2004)

• Appendix C, Classification of Drugs by American Hospital Formulary Service List Number and their ICD-9-CM Equivalents

• Appendix D, Classification of Industrial Accidents According to Agency

• Appendix E, List of Three-Digit Categories

It is important that the health insurance professional thoroughly study the prefacing information contained in the introductory pages because it serves as a basic foundation for diagnostic coding and aids in assigning diagnosis codes correctly.

Volume 2, Alphabetic List (Index)

Because Volume 2, the Alphabetic List, is presented before Volume 1, Tabular List, we discuss it first. Volume 2 contains an alphabetic listing that provides instructions to assist the coder in determining if a diagnosis requires the use of additional or alternative codes. Although it is the starting point for the coding process, a diagnosis should never be coded strictly from the Alphabetic List. After the diagnosis has been abstracted from the patient’s health record, the Alphabetic List is used to guide the coder to the appropriate page in Volume 1 where codes are arranged in numerical order. The exact code can be determined from this numerical list (Volume 1).

Code Structure

A diagnosis code in the ICD-9 structure consists of three to five characters, depending on whether a 3-digit, 4-digit, or 5-digit code best represents the patient’s diagnosis. ICD-9-CM codes range from 001 to V91.99 (2012) and identify symptoms, conditions, problems, complaints, or other reasons for the procedure, service, or supply provided. It is crucial that a diagnosis is coded to the “highest level of specificity.” By consulting the Alphabetic List first, the health insurance professional can determine more accurately whether a 3-digit code sufficiently describes the diagnosis or whether additional numbers are required for specificity. Diagnoses that are coded inadequately or inappropriately can result in a claim being underpaid, overpaid, delayed, or denied.

Three Sections of Volume 2

As discussed previously, Volume 2 (Alphabetic List) is organized alphabetically by medical terms and contains three separate sections or indexes.

Section I, Index to Diseases and Injuries

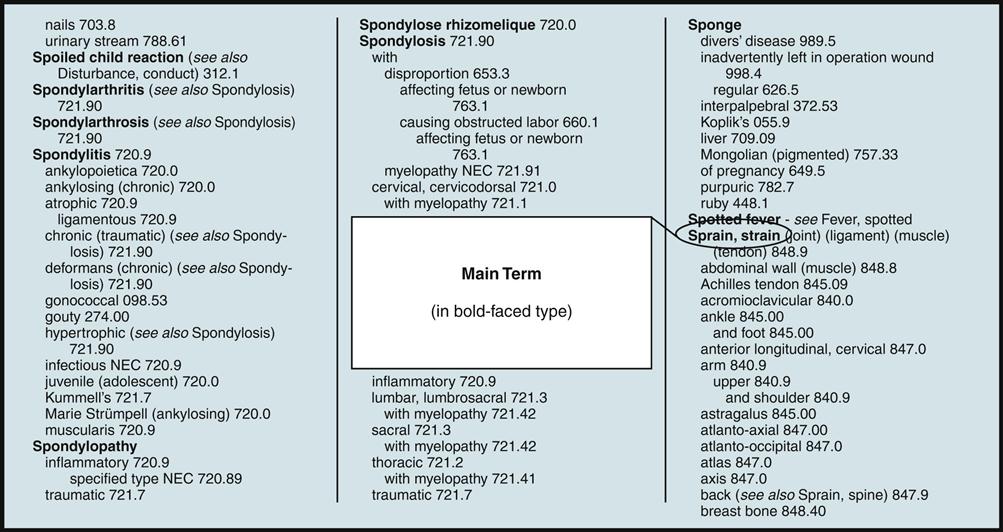

The largest section, the Index to Diseases and Injuries, is organized alphabetically by main terms, which are always printed in boldface type (in the Buck 2012 manual, they are in red font) for easy reference. Main terms include the following:

• Diseases such as influenza or bronchitis

• Conditions such as fatigue, fracture, or injury

• Nouns such as disease, disturbance, syndrome, or eponyms

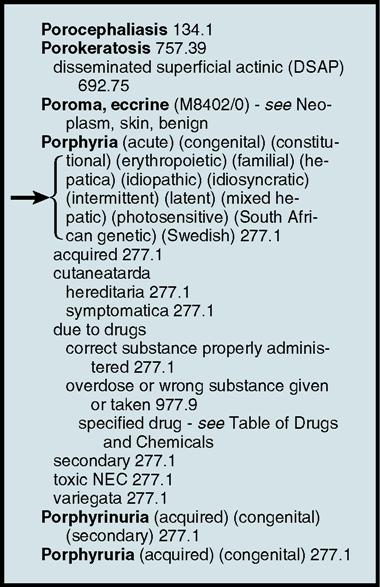

Anatomic sites are not listed as main terms. If a patient has a diagnosis of deviated nasal septum, it would be found in the Alphabetical Index under the main term “deviation,” rather than “nasal.” Ankle sprain would be located under “sprain,” rather than “ankle.” Fig. 12-1 shows a sample page from Volume 2.

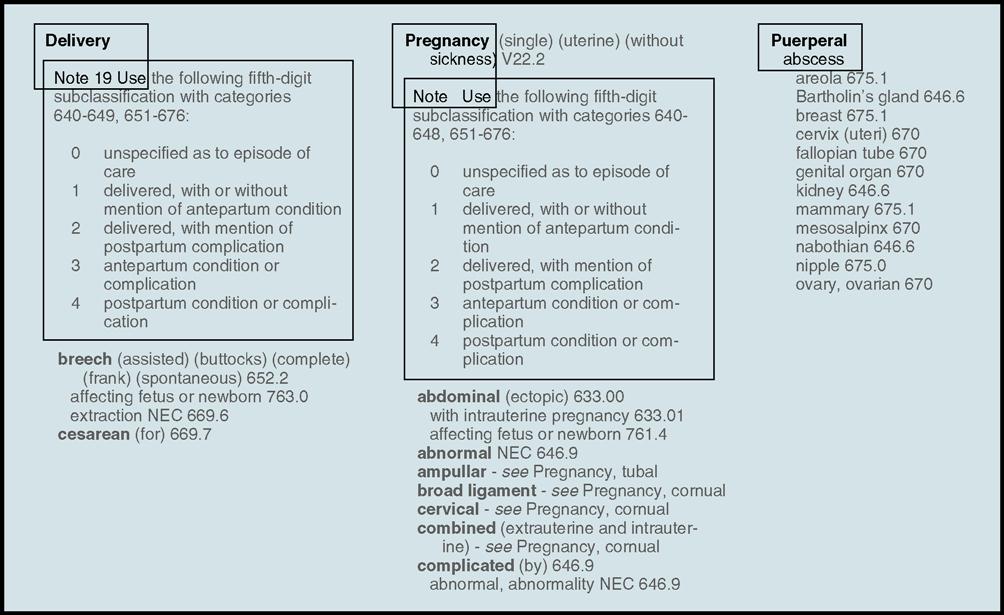

Many conditions can be found in more than one place in the Alphabetic Index, which can be confusing. Obstetric conditions can be found under the name of the condition and under the entries for “delivery,” “pregnancy,” and “puerperal” (after delivery). Fig. 12-2 provides examples of how each of these three terms is shown in Volume 2. Complications of medical and surgical care are indexed under the name of condition and under complications.

Eponyms

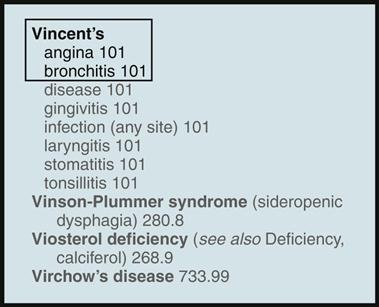

Eponyms are diseases, procedures, or syndromes named for individuals who discovered or first used them. They typically are located alphabetically by the individual’s name and by the common name. Vincent disease (trench mouth) can be found under “Vincent,” “disease,” and “trench” (Fig. 12-3).

Essential Modifiers

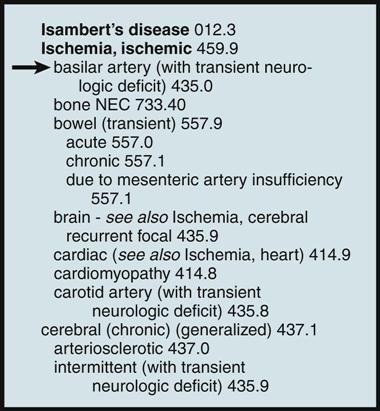

Essential modifiers are indented under the main term as shown in the example in Fig. 12-4. They modify the main term describing different sites, etiology (the cause or origin of a disease or condition), and clinical types. Essential modifiers must be a part of the documented diagnosis.

Nonessential Modifiers

Nonessential modifiers are terms in parentheses after the main terms. They typically give alternative terminology for the main term and are provided to assist the coder in locating the applicable main term. Fig. 12-5 shows an example of how nonessential modifiers are depicted in Volume 2. Nonessential modifiers are usually not a part of the diagnostic statement; however, nonessential modifiers can provide an example of wording that might be in the provider’s notes or diagnostic statement and can reassure the coder that the correct main term has been chosen in the index that directs him or her to the appropriate diagnostic code.

Conventions for Volume 2, Alphabetic Index

Parentheses

Nonessential modifiers are enclosed in parentheses.

Essential modifiers are not enclosed in parentheses and are subterms that do affect the selection of the appropriate code.

See

“See” is a cross-reference directing the coder to look elsewhere for the appropriate code.

See Also

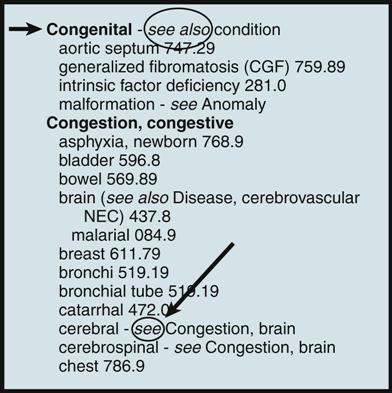

“See also” is a cross-reference directing the coder to locate another main term in the event adequate information cannot be located under the first main term entry. Fig. 12-6 showsexamples of how see and see also are used in Volume 2.

See Category

“See category” is a cross-reference directing the coder to the Tabular List (Vol. 1) for important information applicable to the use of the specific code.

Cross-Reference Notes

Cross-reference notes such as see, see also, see condition, and see category refer the coder to continue the search under another main term. Referring to the patient described in the Stop and Think box with a diagnosis of congestive heart failure, the main term “congestive” and the essential modifier “heart” are located in the Alphabetic Index, and there is a parenthetical notation (see also Failure, heart 428.0). This notation guides the coder to an alternate page in the Index, where the main term “failure, failed” is located. After the essential modifiers (“heart” and “congestive”) code 428.0 is located, the coder must cross-reference this code to the Tabular List to determine if 428.0 describes this diagnosis to its “greatest specificity” or if a fifth digit is necessary.

Other Conventions

Other conventions used in the Alphabetic Index include “Note,” which defines terms and provides coding instructions; “omit code,” which directs the coder not to assign a code for that particular condition; and NEC (“not elsewhere classifiable”), which means that ICD-9-CM does not have a code that describes the condition.

Hypertension and Neoplasm Tables

The Alphabetic Index to Diseases also contains two tables: (1) Hypertension Table and (2) Neoplasm Table. If a patient is diagnosed with essential hypertension (high blood pressure from no apparent cause), the health insurance professional must locate the specific type in the hypertension table and make the determination if it is “malignant,” “benign,” or “unspecified” as indicated in the columnar codes (401.0, 401.1, or 401.9). If the patient’s diagnosis is essential benign hypertension complicating pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperium, the ICD-9 code would be 642.0. As with other code searches, hypertension and neoplasm (new growth) coding does not stop with the indexed tables in Volume 2. In the Buck 2012 manual, a red bullet behind the code indicates additional digits may be necessary to code to the greatest specificity.

Section II, Table of Drugs and Chemicals

Section II of Volume 2 consists of the Table of Drugs and Chemicals, which contains the Alphabetic Index to Poisoning and External Causes of Adverse Effects of Drugs and Other Chemical Substances. Codes in this table are used when documentation in the health record indicates a poisoning, overdose, wrong substance given or taken, or intoxication. The table also lists external causes of adverse effects resulting from ingestion or exposure to drugs or other chemical substances.

Section III, Index to External Causes of Injury and Poisoning (E Codes)

Section III is the Alphabetic Index to External Causes of Injury and Poisoning, which contains E codes. Codes in this section are used to classify environmental events, circumstances, and other conditions that are the cause of injury and other adverse effects. E codes are organized by main terms that describe the accident, circumstance, event, or specific agent causing the injury or adverse effect and should be used in addition to a code from the main body of the classification (Chapters 1 to 17).

National Coverage Determinations and Local Coverage Determinations

In addition to assigning the correct diagnostic code, it is also important to be knowledgeable of Medicare’s National Coverage Determinations (NCDs) and Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs), formerly known as Local Medical Review Policies (LMRPs). NCDs are Medicare’s standard national rules; LCDs are local carriers’ versions of NCDs. These rules specify the services that are allowed for certain diagnoses. Databases of Medicare carriers screen ICD-9/CPT coding pairs to ensure they correspond to LCDs and automatically deny coding pairs that do not correspond. Because LCDs do not exist for all services and focus primarily on diagnostic tests, some claims are not affected by this screening method.

LCDs can change frequently; it is important to keep up-to-date by frequently checking the Medicare website by following the link available on the  Evolve site. Select both the NCDs and LCDs boxes in the first section of the search page. Private payer rules can differ from Medicare rules in allowing certain services with a particular diagnosis. Most payers post their determinations on their websites.

Evolve site. Select both the NCDs and LCDs boxes in the first section of the search page. Private payer rules can differ from Medicare rules in allowing certain services with a particular diagnosis. Most payers post their determinations on their websites.

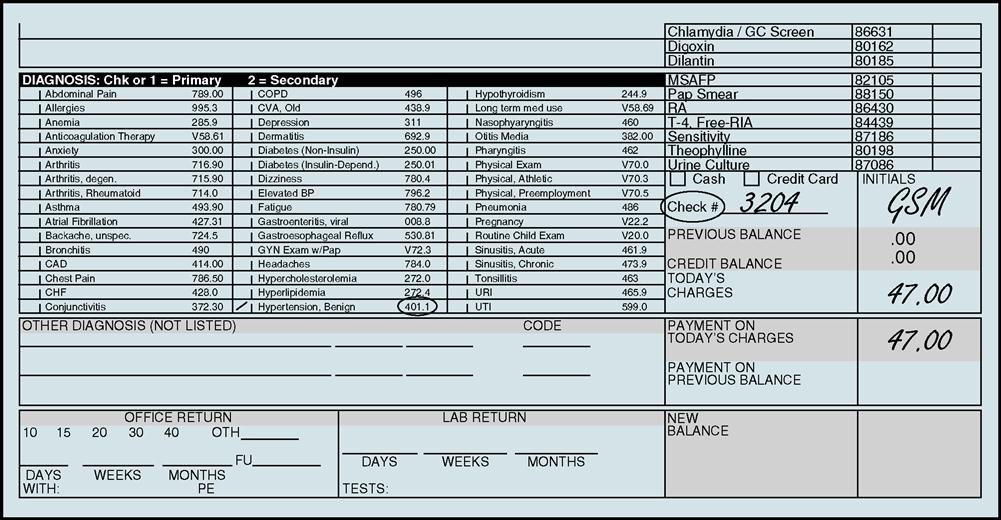

Process of classifying diseases

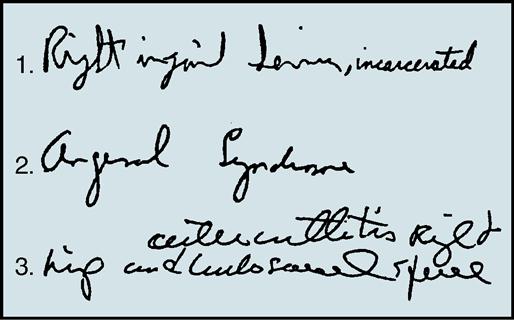

The first thing that the coder must do in the coding process is to locate the diagnosis in the health record. This task can be straightforward sometimes because many encounter forms list the more frequently used diagnoses within a certain medical specialty along with their corresponding ICD-9 codes (Fig. 12-7). Other times, the coder may have to refer to the clinical notes to locate the diagnosis. If the notes are handwritten, deciphering the healthcare professional’s handwriting sometimes can be challenging (Fig. 12-8). With practice and experience, locating the diagnosis within the clinical notes and translating a physician’s handwriting become easier.

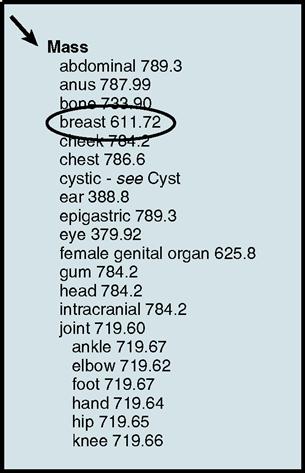

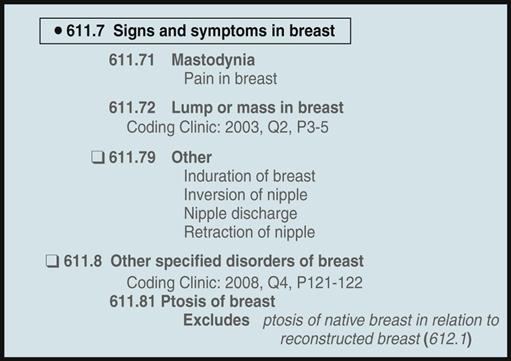

After the diagnosis has been determined, the main term within the diagnosis should be identified. For example, if the diagnosis is “breast mass,” the main term would be “mass.” (The anatomic site “breast” is not used in the Alphabetic Index to Diseases.) Fig. 12-9 illustrates how the main term “mass” appears in Volume 2.

Note the numbers 611.72 following “breast” shown in the portion of Volume 2 in Fig. 12-10. This is the 5-digit diagnosis code for breast mass. The number one cardinal rule in coding is never to code from the Alphabetic Index (Volume 2) alone. Before assigning this code, it is important to read any special notes or instructions, after which the health insurance professional turns to Volume 1, the Tabular Index, and locates the code 611.72.

Volume 1, Tabular List

Volume 1, the Tabular List, contains 17 sections representing anatomic systems or types of conditions. These 17 sections were listed under the main heading entitled “ICD-9-CM Coding Manual.” The titles describe the content of the section followed by the range of codes in a specific category.

Organization of Volume 1 Codes

There are three types of codes in Volume 1:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree