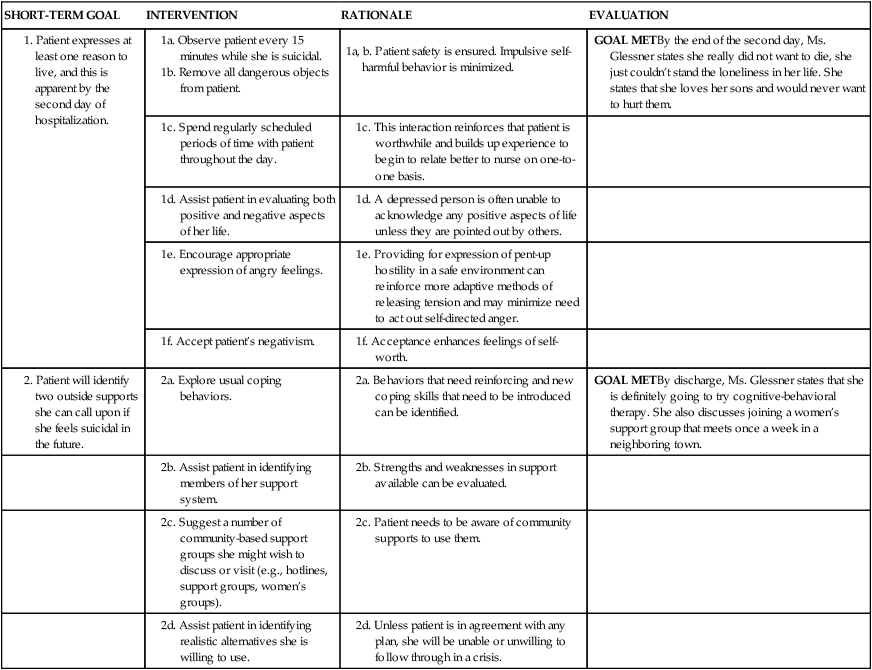

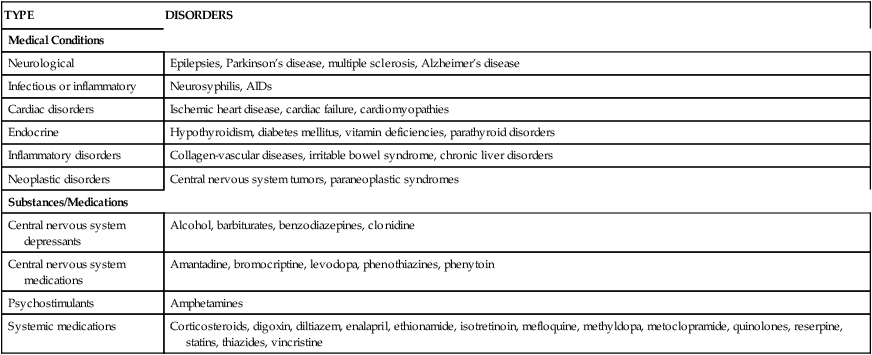

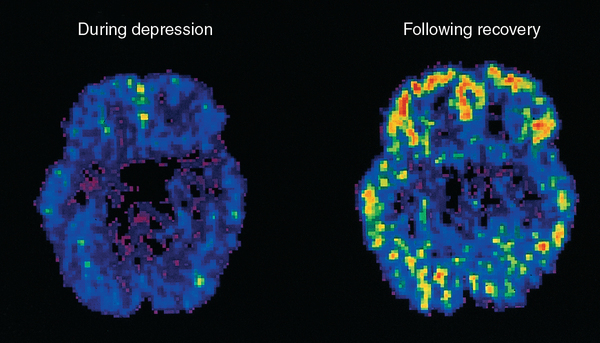

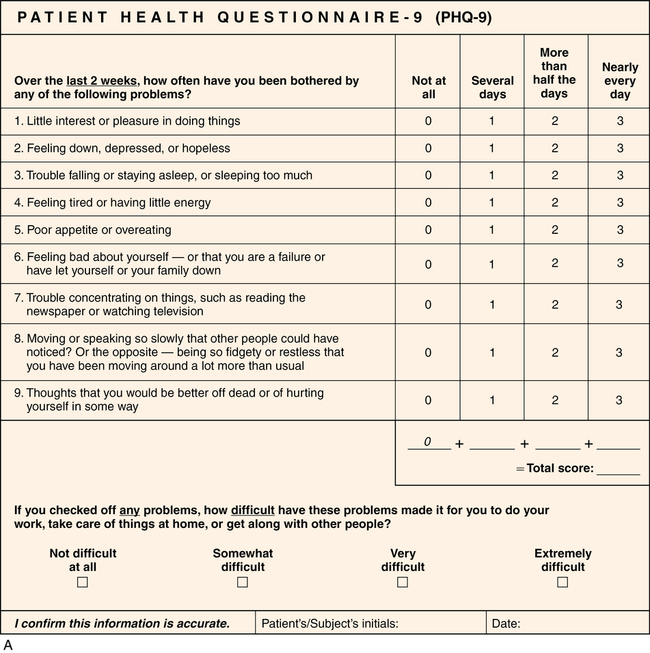

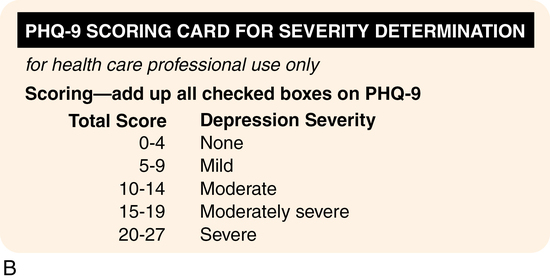

CHAPTER 14 Mallie Kozy and Margaret Jordan Halter 1. Compare and contrast major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder. 2. Explore disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and its impact on children. 3. Describe the symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. 4. Discuss the complex origins of depressive disorders. 5. Assess behaviors in a patient with depression in regard to each of the following areas: (a) affect, (b) thought processes, (c) feelings, (d) physical behavior, and (e) communication. 6. Formulate five nursing diagnoses for a patient with depression, and include outcome criteria. 7. Name unrealistic expectations a nurse may have while working with a patient with depression, and compare them to your own personal thoughts. 8. Role-play six principles of communication useful in working with patients with depression. 9. Evaluate the advantages of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) over the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). 10. Explain the unique attributes of two of the unconventional antidepressants for use in specific circumstances. 11. Write a medication teaching plan for a patient taking a tricyclic antidepressant, including (a) adverse effects, (b) toxic reactions, and (c) other drugs that can trigger an adverse reaction. 12. Write a medication teaching plan for a patient taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, including foods and drugs that are contraindicated. 13. Write a nursing care plan incorporating the recovery model of mental health. 14. Discuss the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depressive disorders. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, 2012b), major depressive disorder is one of the most common mental disorders, affecting approximately 13 million adults annually in the United States. Major depressive disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, dysthymic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, substance-induced depressive disorder, and depressive disorder not elsewhere classified are all disorders included in the category of depressive disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fifth edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In depression a person can be abnormally preoccupied with death. This may be exhibited in the patient by fantasizing about his or her funeral or having recurring dreams about death. It is not uncommon for patients with depression to become suicidal. Suicidal thoughts may be relatively mild and fleeting. For other individuals, suicidal thoughts are quite serious or persistent and involve a plan. Suicidal thoughts, especially those in which the patient has a plan and the means to carry it out, represent an emergency requiring immediate intervention by the nurse (refer to Chapter 25) Suicidal thoughts are a major reason for hospitalization for patients with major depression. Major depression can occur just once in a patient’s lifetime or it can remit and recur. In bipolar disorder, patients may also experience depression that remits and recurs; however, patients with major depression differ from patients with bipolar disorder in that they experience no episodes of mania or hypomania (refer to Chapter 13). Depressive disorders are classified according to symptoms or the situations under which they occur. The incidence of major depression greatly increases with the occurrence of a medical disorder, and people with chronic medical problems are at a higher risk for depression than those in the general population. Depression often develops secondary to a medical condition and may also be secondary to use of substances such as alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, heroin, and even anxiolytics and other prescription medications (Table 14-1). Depression can also be a consequence of bereavement and grief. TABLE 14-1 DEPRESSION SECONDARY TO MEDICAL CONDITIONS AND SUBSTANCES/MEDICATIONS From Joska, J. A., & Stein, D. J. (2008). Mood disorders. In R. E. Hales, S. C. Yudofsky, & G. O. Gabbard (Eds.), Textbook of psychiatry (5th ed., p. 464). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. Although many theories attempt to explain the cause of depression, many psychological, biological, and cultural variables make identification of any one cause difficult; furthermore, it is unlikely there is a single cause for depression. The high variability in symptom manifestation, response to treatment, and course of the illness supports the supposition that depression may result from a complex interaction of causes. For example, genetic predisposition to the illness combined with childhood stress may lead to significant changes in the central nervous system (CNS) that result in depression; however, there seem to be several common risk factors for depression, listed in Box 14-1 (Sadock & Sadock, 2008). At this time, no single mechanism of depressant action has been found. The relationships among the serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, acetylcholine, GABA, and glutamate systems are complex and need further assessment and study; however, treatment with medication that helps regulate these neurotransmitters has proved empirically successful in the treatment of many patients. Figure 14-1 shows a positron emission tomographic (PET) scan of the brain of a woman with depression before and after taking medication. Refer to Chapter 3 for further discussion of brain imaging and depression. Numerous standardized depression-screening tools that help assess the type and severity of depression are available, including the Beck Depression Inventory, the Hamilton Depression Scale, the Zung Depression Scale, and the Geriatric Depression Scale. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a short inventory that highlights predominant symptoms seen in depression, is presented here because of its ease of use (Figure 14-2) in primary care and community settings. It is important to note that self-screening tools such as the PHQ-9 have been validated, meaning they screen for depression with 91% accuracy, providing a valuable tool for the nurse (Gilbody, Richards & Barkham, 2007). Use of these tools during multiple encounters with a patient also allows the nurse to follow changes in the patient’s symptoms and depression severity over time. The website www.depression-screening.org, sponsored by the National Mental Health Association (NMHA), enables people to take an online confidential screening test for depression and find reliable information on the illness (Live your life, 2009). • You have said you are depressed. Tell me what that is like for you. • When you feel depressed, what thoughts go through your mind? • Have you gone so far as to think about taking your own life or hurting yourself in some way? Do you have a plan? • Do you have the means to carry out your plan? • Is there anything that would prevent you from carrying out your plan? Refer to Chapter 25 for a detailed discussion of suicide, critical risk factors, warning signs, and strategies for suicide prevention. Also see Case Study and Nursing Care Plan 14-1.

Depressive disorders

![]() http://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/ST/halter7epre/index.html?location=halter/four/fourteen%0d

http://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/ST/halter7epre/index.html?location=halter/four/fourteen%0d

Clinical picture

Comorbidity

TYPE

DISORDERS

Medical Conditions

Neurological

Epilepsies, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease

Infectious or inflammatory

Neurosyphilis, AIDs

Cardiac disorders

Ischemic heart disease, cardiac failure, cardiomyopathies

Endocrine

Hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, vitamin deficiencies, parathyroid disorders

Inflammatory disorders

Collagen-vascular diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic liver disorders

Neoplastic disorders

Central nervous system tumors, paraneoplastic syndromes

Substances/Medications

Central nervous system depressants

Alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, clonidine

Central nervous system medications

Amantadine, bromocriptine, levodopa, phenothiazines, phenytoin

Psychostimulants

Amphetamines

Systemic medications

Corticosteroids, digoxin, diltiazem, enalapril, ethionamide, isotretinoin, mefloquine, methyldopa, metoclopramide, quinolones, reserpine, statins, thiazides, vincristine

Etiology

Biological factors

Biochemical

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

General assessment

Assessment tools

Assessment of suicide potential

Areas to assess

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree