Culture and Ethnicity

Objectives

• Describe social and cultural influences in health, illness, and caring patterns.

• Differentiate culturally congruent from culturally competent care.

• Describe steps toward developing cultural competence.

• Identify major components of cultural assessment.

• Demonstrate nursing interventions that achieve culturally congruent care.

• Analyze outcomes of culturally congruent care.

Key Terms

Acculturation, p. 103

Assimilation, p. 103

Biculturalism, p. 103

Bilineal, p. 111

Culture, p. 102

Cultural care accommodation or negotiation, p. 113

Cultural care preservation or maintenance, p. 113

Cultural care repatterning or restructuring, p. 113

Cultural competence, p. 103

Cultural imposition, p. 103

Cultural pain, p. 107

Culturally congruent care, p. 103

Culture-bound syndrome, p. 104

Emic worldview, p. 102

Enculturation, p. 103

Ethnicity, p. 102

Ethnohistory, p. 107

Ethnocentrism, p. 103

Etic worldview, p. 102

Fictive, p. 111

Matrilineal, p. 111

Naturalistic practitioners, p. 104

Patrilineal, p. 111

Personalistic practitioners, p. 104

Rites of passage, p. 105

Subcultures, p. 102

Transcultural nursing, p. 103

![]()

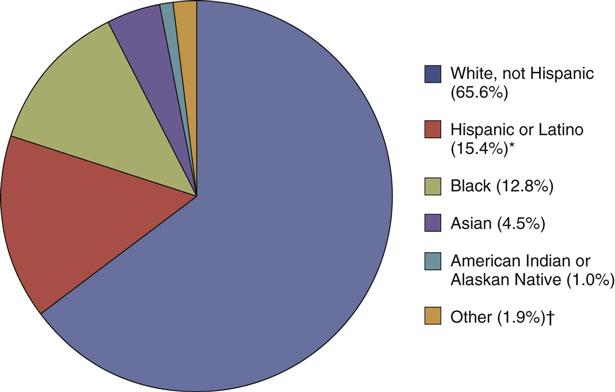

The demographic profile of the United States is changing dramatically as a result of immigration patterns and significant increases in culturally diverse populations already residing in the country. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 33% of the population currently belongs to a racial or ethnic minority group (Fig. 9-1). The U.S. Census also projects that this percentage will increase to 50% by the year 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Because it is important to care for people holistically, nurses need to integrate culturally congruent care within their nursing practice.

Health Disparities

Despite significant improvements in the overall health status of the U.S. population in the last few decades, disparities in health status among ethnic and racial minorities continues to be a serious local and national challenge. The Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities (2007a) reports that minority populations are more likely to have poor health and die at an earlier age because of a complex interaction among genetic differences, environmental and socioeconomic factors, and specific health behaviors such as the use of herbs to prevent or treat illnesses. Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than white non-Hispanics to be poor or near poor. In addition, Hispanics, African Americans, and some Asian subgroups are less likely than white non-Hispanics to have a high school education. In general, racial and ethnic minorities often experience poorer access to health care and lower quality of preventive, primary, and specialty care. Eliminating such disparities in health status of people from diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds has become one of the two most important priorities of Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010). Populations with health disparities have a significantly increased incidence of diseases or increased morbidity and mortality when compared to the health status of the general population.

Understanding Cultural Concepts

The Office of Minority Health (OMH) (2005) describes culture as the thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions of racial, ethnic, religious, or social groups. Culture is a concept that applies to a group of people whose members share values and ways of thinking and acting that are different from those of people who are outside the group (Srivastava, 2007).

Culture has both visible (easily seen) and invisible (less observable) components. The invisible value-belief system of a particular culture is often the major driving force behind visible practices. For example, although an Apostolic Pentecostal woman can be identified by her long hair, no makeup, and the wearing of a skirt or dress, nurses cannot appreciate the meanings and beliefs associated with her appearance without further assessment. Apostolic Pentecostals believe that a woman’s hair is her glory and should never be cut. Likewise, they believe that men and women need to dress differently and women need to be modest (wearing no makeup). These outward signs symbolize their belief in the scriptural definition of womanhood (United Pentecostal Church International, 2011). Cutting a woman’s hair without consent of the individual or her family is sacrilegious and violates the ethnoreligious identity of the person. On the other hand, a woman of another faith who wears her hair long does not attach meaning to the length of her hair but wears it long because of a fashion preference.

In any society there is a dominant culture that exists along with other subcultures. Although subcultures have similarities with the dominant culture, they maintain their unique life patterns, values, and norms. In the United States the dominant culture is Anglo-American with origins from Western Europe. Subcultures such as the Appalachian and Amish cultures are examples of ethnic and religious groups with characteristics distinct from the dominant culture. Primary and secondary characteristics of culture are defined by the degree to which an individual identifies with his or her cultural group. Primary characteristics include nationality, race, gender, age, and religious beliefs. Secondary characteristics include socioeconomic and immigration status, residential patterns, personal beliefs, and political orientation.

Significant influences such as historical and social realities shape an individual’s or group’s worldview. Worldview is woven into the fabric of one’s culture. It determines how people perceive others, how they interact and relate with reality, and how they process information (Walker et al., 2010). It is important that the nurse advocates for the patient based on the patient’s worldview. Plan and provide nursing care in partnership with the patient to ensure that it is safe, effective, and culturally sensitive (McFarland and Eipperle, 2008).

Ethnicity refers to a shared identity related to social and cultural heritage such as values, language, geographical space, and racial characteristics. Members of an ethnic group feel a common sense of identity. Some declare their ethnic identity to be Irish, Vietnamese, or Brazilian. Ethnicity is different from race, which is limited to the common biological attributes shared by a group such as skin color (Dein, 2006). Examples of racial classifications include Asian and Caucasian.

Worldview refers to “the way people tend to look out upon the world or their universe to form a picture or value stance about life or the world around them” (Leininger, 2006). In any intercultural encounter there is an insider or native perspective (emic worldview) and an outsider perspective (etic worldview). For example, after giving birth, a Korean woman requests seaweed soup for her first meal. This request puzzles the nurse. Although the nurse has an emic view of professional postpartum care, as an outsider to the Korean culture he or she is not aware of the significance of the soup to the patient. Conversely, the Korean patient who has an etic view of American professional care assumes that seaweed soup is available in the hospital because it cleanses the blood and promotes healing and lactation (Edelstein, 2011). Unless the nurse seeks the patient’s emic view, he or she is likely to suggest other varieties of soups available from the dietary department, disregarding the cultural meaning of the practice to the patient.

The processes of enculturation and acculturation facilitate cultural learning. Socialization into one’s primary culture as a child is known as enculturation. In contrast, acculturation is a second-culture learning that occurs when the culture of a minority is gradually displaced by the culture of the dominant group in the process of assimilation (Cowan and Norman, 2006). When the process of assimilation occurs, members of an ethnocultural community are absorbed into another community and lose their unique characteristics such as language, customs, and ethnicity. Assimilation may be spontaneous, which is usually the case with immigrants, or forced, as is often the case of the assimilation of ethnic minority communities. Biculturalism (sometimes known as multiculturalism) occurs when an individual identifies equally with two or more cultures (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

It is easy for nurses to stereotype cultural groups after reading generalized information about various ethnic minority practices and beliefs (Dein, 2006). Avoid stereotypes or unwarranted generalizations about any particular group that prevents further assessment of the individual’s unique characteristics. It is also important to determine how many of an individual’s life patterns are consistent with his or her heritage (Armer and Radina, 2006).

Culturally Congruent Care

Leininger (2002) defines transcultural nursing as a comparative study of cultures to understand similarities (culture universal) and differences (culture-specific) across human groups. The goal of transcultural nursing is culturally congruent care, or care that fits the person’s life patterns, values, and a set of meanings. Patterns and meanings are generated from people themselves rather than predetermined criteria. Culturally congruent care is sometimes different from the values and meanings of the professional health care system. Discovering patients’ culture care values, meanings, beliefs, and practices as they relate to nursing and health care requires nurses to assume the role of learners and partner with patients and families in defining the characteristics of meaningful and beneficial care (Leininger and McFarland, 2002). Effective nursing care needs to integrate the cultural values and beliefs of individuals, families, and communities (Webber, 2008).

Cultural competence is the process of acquiring specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes to ensure delivery of culturally congruent care (Campinha-Bacote, 2002). This process has five interlocking components:

Specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes are required in the delivery of culturally congruent care to individuals and communities. Nurses who provide culturally competent care bridge cultural gaps to provide meaningful and supportive care for patients. For example, a nurse assigned to a female Egyptian patient decides to seek information about the Egyptian culture. On learning that Egyptians value female modesty and gender-congruent care, the nurse encourages female relatives to help the patient meet her needs for personal hygiene. The nurse’s cultural encounter enhances understanding of the nonverbal cues of the patient’s discomfort with lack of privacy.

Implementing culturally competent care requires support from health care agencies. For example, a nurse who is aware of Gypsy culture and skilled in dealing with Gypsy families is not able, as an individual, to provide for a Gypsy family’s need to be present in groups near the bedside of a hospitalized family member. The nurse needs organizational support in adapting space resources to accommodate the volume of visitors who will remain with the patient for long periods.

Because patients who seek care could be from countless different world cultures, it is unlikely that a nurse could be competent in all cultures of the world. However, nurses can have general knowledge and skills to prepare them to provide culturally sensitive care, regardless of the patient’s and family’s culture (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Cultural Conflicts

Culture provides the context for valuing, evaluating, and categorizing life experiences. Cultural groups transmit their values, morals, and norms from one generation to another, which predisposes members to ethnocentrism, a tendency to hold one’s own way of life as superior to others. Ethnocentrism is the cause of biases and prejudices that associate negative permanent characteristics with people who are different from the valued group. When a person acts on these prejudices, discrimination occurs. For example, a nurse refuses to give prescribed pain medication to a young African male with sickle cell anemia because of the nurse’s belief (stereotyped bias) that young male Africans are likely to be drug abusers. Nurses and other health care providers who have cultural ignorance or cultural blindness about differences generally resort to cultural imposition and use their own values and lifestyles as the absolute guide in dealing with patients and interpreting their behaviors. Thus a nurse who believes that people should bear pain quietly as a demonstration of strong moral character is annoyed when a patient insists on having pain medication and denies the patient’s discomfort.

Cultural Context of Health and Caring

Culture is the way in which groups of people make sense of their experiences relevant to life transitions such as birth, illness, and dying. For example, in most African groups a thin body is a sign of poor health. In some Hispanic cultures a plump baby is perceived as healthy. Traditionally in Arab culture pregnancy is not a medical condition but rather a normal life transition; thus a pregnant woman does not always go to a health care provider unless she has a problem (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

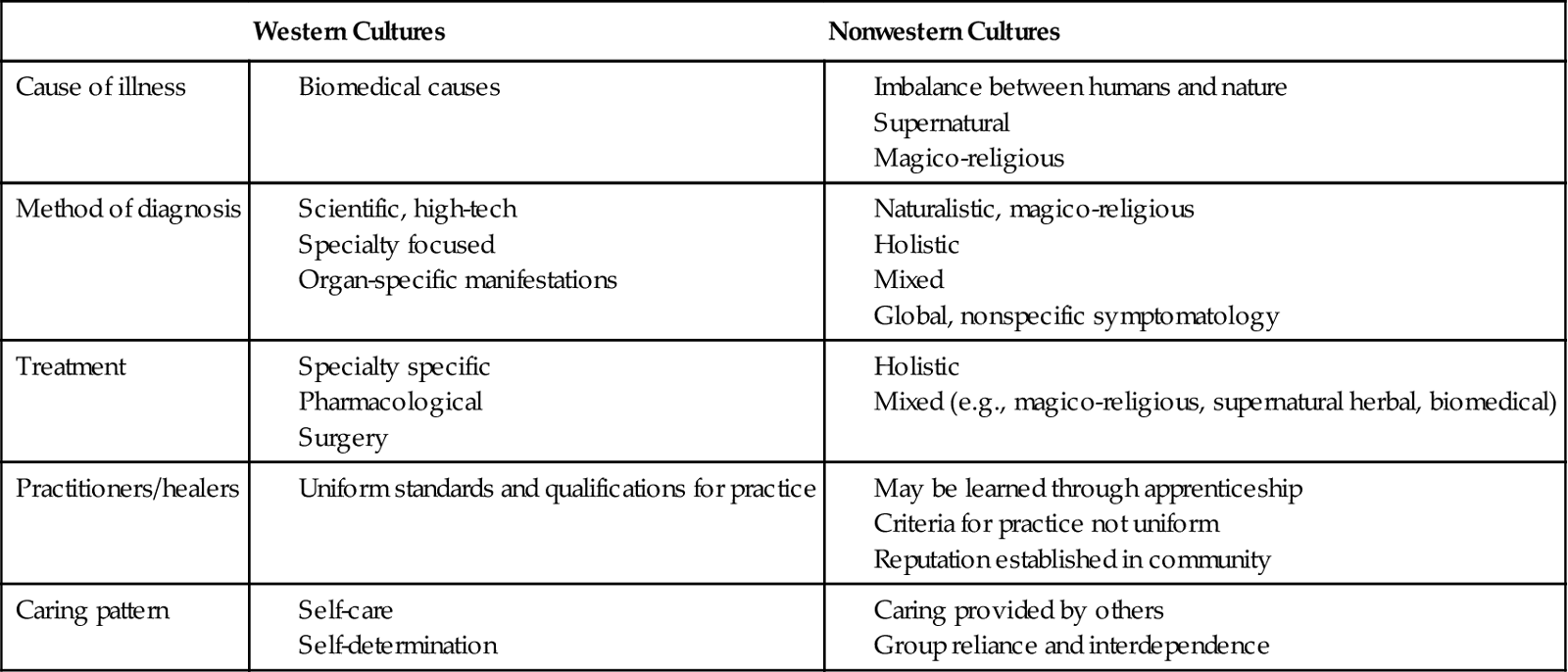

Table 9-1 provides a comparison of cultural contexts of health and illness in western and nonwestern cultures. Cultural beliefs highly influence what people believe to be the cause of illness. For example, many Hmong refugees (group of people who originated from the mountainous regions of Laos) believe that epilepsy is caused by the wandering of the soul. Treatment includes intervention by a shaman who performs a ritual to retrieve the patient’s soul (Fadiman, 1997; Helsel et al., 2005). Their belief is distinct from the scientifically determined neurological abnormality causing seizures. The biomedical orientation of western cultures emphasizing scientific investigation and reducing the human body to distinct parts is in conflict with the holistic conceptualization of health and illness in nonwestern cultures. Holism is evident in the belief in continuity between humans and nature and between human events and metaphysical and magico-religious phenomena. Therefore for the Hmong people epilepsy is connected to the magical and supernatural forces in nature. Establishing a diagnosis of epilepsy in western cultures requires scientifically proven techniques and confirmed criteria for the abnormality. Such medical criteria are meaningless to the Hmong, who believe in the global causation of the illness that goes beyond the mind and body of the person to forces in nature. A Hmong seeks a shaman, whereas a westerner seeks a neurologist. A shaman has an established reputation in the Hmong community, whose qualifications for healing are neither determined by published standardized criteria nor confined to specific bodily systems. A shaman uses rituals symbolizing the supernatural, spiritual, and naturalistic modalities of prayers, herbs, and incense burning.

TABLE 9-1

Comparative Cultural Contexts of Health and Illness

| Western Cultures | Nonwestern Cultures | |

| Cause of illness | ||

| Method of diagnosis | ||

| Treatment | ||

| Practitioners/healers | ||

| Caring pattern |

Data from Foster G: Disease etiologies in non-Western medical systems, Am Anthropol 78:773,1976; Kleinman A: Patients and healers in the context of culture, Berkeley, 1979, University of California Press; and Leininger MM, McFarland MR: Transcultural nursing: concepts, theories, research and practice, ed 3, New York, 2002, McGraw-Hill.

The dominant value orientation in North American society is individualism and self-reliance in achieving and maintaining health. Caring approaches generally promote the patient’s independence and ability for self-care. In collectivistic cultures that value group reliance and interdependence such as traditional Asians, Hispanics, and Africans, caring behaviors require actively providing physical and psychosocial support for family or community members. An adult patient is not expected to be solely responsible for his or her care and well-being; rather, family and kin are relied on to make decisions and provide care (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008). For example, a traditional older Chinese woman refuses to independently perform rehabilitation exercises after hip surgery until her daughter is present. The western health care provider interprets this as a lack of self-responsibility and motivation for her care. In contrast, the patient interprets the nurse’s insistence on self-care as uncaring behavior.

Cultural Healing Modalities and Healers

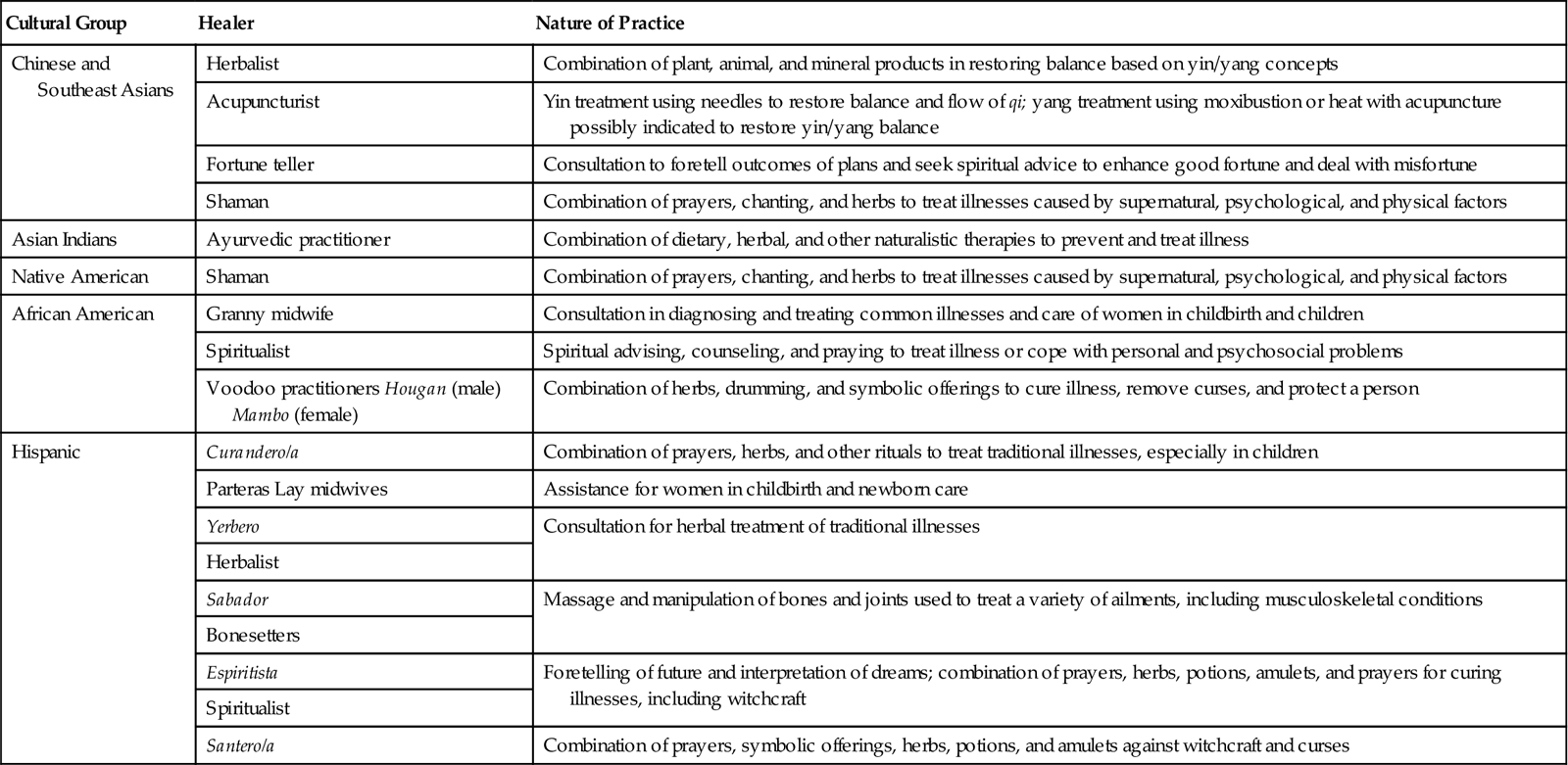

Foster (1976) identified two distinct categories of healers cross-culturally. Naturalistic practitioners attribute illness to natural, impersonal, and biological forces that cause alteration in the equilibrium of the human body. Healing emphasizes use of naturalistic modalities, including herbs, chemicals, heat, cold, massage, and surgery. In contrast, personalistic practitioners believe that an external agent, which can be human (i.e., sorcerer) or nonhuman (e.g., ghosts, evil, or deity), causes health and illness. Personalistic beliefs emphasize the importance of humans’ relationships with others, both living and deceased, and with their deities. For example, a voodoo priest uses modalities that combine supernatural, magical, and religious beliefs through the active facilitation of an external agent or personalistic practitioner. A Haitian woman who believes in voodoo attributes her illness to a curse placed by someone and seeks the services of a voodoo priest to remove the cause. Personalistic approaches also include naturalistic modalities such as massage, aromatherapy, and herbs (see Chapter 32). Some patients seek both types of practitioners and use a combination of modalities to achieve health and treat illness. Different cultural groups in the United States use a variety of cultural healers (Table 9-2).

TABLE 9-2

| Cultural Group | Healer | Nature of Practice |

| Chinese and Southeast Asians | Herbalist | Combination of plant, animal, and mineral products in restoring balance based on yin/yang concepts |

| Acupuncturist | Yin treatment using needles to restore balance and flow of qi; yang treatment using moxibustion or heat with acupuncture possibly indicated to restore yin/yang balance | |

| Fortune teller | Consultation to foretell outcomes of plans and seek spiritual advice to enhance good fortune and deal with misfortune | |

| Shaman | Combination of prayers, chanting, and herbs to treat illnesses caused by supernatural, psychological, and physical factors | |

| Asian Indians | Ayurvedic practitioner | Combination of dietary, herbal, and other naturalistic therapies to prevent and treat illness |

| Native American | Shaman | Combination of prayers, chanting, and herbs to treat illnesses caused by supernatural, psychological, and physical factors |

| African American | Granny midwife | Consultation in diagnosing and treating common illnesses and care of women in childbirth and children |

| Spiritualist | Spiritual advising, counseling, and praying to treat illness or cope with personal and psychosocial problems | |

| Voodoo practitioners Hougan (male) Mambo (female) | Combination of herbs, drumming, and symbolic offerings to cure illness, remove curses, and protect a person | |

| Hispanic | Curandero/a | Combination of prayers, herbs, and other rituals to treat traditional illnesses, especially in children |

| Parteras Lay midwives | Assistance for women in childbirth and newborn care | |

| Yerbero | Consultation for herbal treatment of traditional illnesses | |

| Herbalist | ||

| Sabador | Massage and manipulation of bones and joints used to treat a variety of ailments, including musculoskeletal conditions | |

| Bonesetters | ||

| Espiritista | Foretelling of future and interpretation of dreams; combination of prayers, herbs, potions, amulets, and prayers for curing illnesses, including witchcraft | |

| Spiritualist | ||

| Santero/a | Combination of prayers, symbolic offerings, herbs, potions, and amulets against witchcraft and curses |

Data from Hautman MA: Folk health and illness beliefs, Nurse Pract 4(4):23, 1976; Loustaunau MO, Sobo EJ: The cultural context of health, illness and medicine, Westport, Conn, 1997; Spector RE: Cultural diversity in health and illness, ed 6, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 2004, Prentice Hall.

Avoid making rash judgments about patients’ practices when they use both healing systems at the same time. In addition, gain knowledge and understanding of remedies used by patients to prevent cultural imposition. For example, many Southeast Asian cultures practice folk remedies such as coining (rubbing a coin roughly on the skin), cupping (placing heated cups on the skin), pinching, and burning to relieve aches and pains and remove bad wind or noxious elements that cause illness. Other groups, including eastern Europeans, use cupping as treatment for respiratory ailments. These remedies leave peculiar visible markings on the skin in the form of ecchymosis, superficial burns, strap marks, or local tenderness. Cultural ignorance of these practices causes a practitioner to call authorities for suspicion of abuse.

Culture-Bound Syndrome

Human groups create their own interpretation and descriptions of biological and psychological malfunctions within their unique social and cultural context (Dein, 2006). Culture-bound syndromes are illnesses that are specific to one culture. They are used to explain personal and social reactions of the members of the culture. Culture-bound syndromes occur in any society. In the United States “going postal,” which refers to extreme and uncontrollable anger in the workplace that may result in shooting people, is now considered a culture-bound syndrome (Flaskerud, 2009). Hwa-byung is a Korean culture-bound syndrome observed among middle-age, low-income women who are overwhelmed and frustrated by the burden of caregiving for their in-laws, husbands, and children. Symptoms are generally somatic manifestations consisting of insomnia, fatigue, anorexia, indigestion, feelings of an epigastric mass, palpitations, heat, panic, feelings of impending doom, and dyspnea. Women unconsciously avoid expressions of symptoms that counter the cultural ideal of females as the caretaker of older adults, husbands, and children. Symptoms reflect the cultural definition of illness as imbalance between heat (yang) and cold (yin) (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Culture and Life Transitions

Cultures generally mark transitions to different phases of life by rituals that symbolize cultural values and meanings attached to these life passages. Van Gennep (1960) originated the concept of rites of passage as significant social markers of changes in a person’s life. Examining the practices surrounding these life events provides a view of the cultural meanings and expressions relevant to these transitions. For example, sending flowers and get-well greetings to a sick person is a ritual showing love and care for the patient in the dominant American culture in which privacy is valued. In collectivistic groups such as the Hispanic culture, physical presence of loved ones with the patient during illness demonstrates caring.

Pregnancy

All cultures value reproduction because it promotes continuity of the family and community. Pregnancy is generally associated with caring practices that symbolize the significance of this life transition in women. Infertility in a woman is considered grounds for divorce and rejection among Arabs. Pregnancy that occurs outside of accepted societal norms is generally taboo. Among traditional Muslims pregnancy out of wedlock sometimes results in the family’s imposing severe sanctions against the female member (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Some cultures that subscribe to the hot and cold theory of illness such as many Asian and Hispanic cultures view pregnancy as a hot state; thus they encourage cold foods such as milk and milk products, yogurt, sour foods, and vegetables (Edelstein, 2011). They believe that hot foods such as chilies, ginger, and animal products cause miscarriage and fetal abnormality. Modesty is a strong value among Afghan (Omeri et al., 2006) and Arab women (Kulwicki et al., 2005). These women sometimes avoid or refuse to be examined by male health care providers because of embarrassment. Religious beliefs sometimes interfere with prenatal testing, as in the case of a Filipino couple refusing amniocentesis because they believe that the outcome of pregnancy is God’s will and not subject to testing.

Childbirth

How individuals express pain and the expectation about how to treat suffering varies cross-culturally and in different religions. For example, Vietnamese women are often stoic regarding the pain of childbirth because their culture views childbirth pain as a normal part of life (McLachlan and Waldenstrom, 2005). Traditional Puerto Rican and Mexican women often vocalize their pain during labor and avoid breathing through their mouths because this causes the uterus to rise. Traditional Arab Americans are sometimes physically or verbally more expressive when experiencing pain. Fear of drug addiction and the belief that pain is a form of spiritual atonement for one’s past deeds motivate most Filipino mothers to tolerate pain without much complaining or asking for medication. Religious beliefs sometimes prohibit the presence of males, including husbands, from the delivery room. This often occurs among devout Muslims, Hindus, and Orthodox Jews (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Health care providers other than physicians attend childbirth in some groups such as parteras among Mexicans, herb doctors among Appalachian and southern African Americans, and hilots among Filipinos (Nelms and Gorski, 2006). Known in their communities, these practitioners are affordable and accessible in remote areas. They use a combination of naturalistic, religious, and supernatural modalities combining herbs, massage, and prayers.

Newborn

The definition of newborn and how age is counted in children varies in some cultures. Among traditional Vietnamese and Koreans a newborn is 1 year old at birth. Once acculturated to the U.S. culture, they assume a bicultural view, deducting 1 year from the age of the child when speaking to an outsider. Naming ceremonies vary by culture. In the Yoruba tribes in Nigeria, the baby is named at the official naming ceremony that occurs 8 days after birth and coincides with circumcision. Many cultures around the world greatly celebrate the birth of a son, including Chinese, Asian Indians, Islamic groups, and Igbos in West Africa.

The name of the child often reflects cultural values of the group. It is typical for a Hispanic baby to have several first names followed by the surnames of the father and mother (e.g., Maria Kristina Lourdes Lopez Vega). The bilineal tracing of descent from both the mother’s and father’s side in Hispanic groups differs from the patrilineal system, in which the last name of the father precedes the child’s first name. In the Chinese culture individuals trace descent only from the paternal side. Thus the name Chen Lu means that Lu is the daughter of Mr. Chen.

Newborns and young children are often considered vulnerable, and societies use a variety of ways to prevent harm to the child. Among the mostly Catholic Filipinos, parents keep the newborn inside the home until after the baptism to ensure the baby’s health and protection. Traditional Arabs and Iranians believe that babies are vulnerable to cold and wind; thus they wrap them in blankets.

Postpartum Period

In many nonwestern cultures the postpartum period is associated with vulnerability of the mother to cold. To restore balance mothers do not shower and take sponge baths. Some groups have special dietary practices to restore balance. Cultural groups have preferences in terms of what types of foods are appropriate to restore balance in women after birth. Some Chinese mothers prefer soups, rice, rice wine, and eggs; whereas Guatemalan women avoid beans, eggs, and milk during the postpartum period (Edelstein, 2011). The length of the postpartum period is generally much longer (30 to 40 days) in nonwestern cultures to provide support for the mother and her baby (Chin et al., 2010).

Filipino, Mexicans, and Pacific Islanders use an abdominal binder to prevent air from entering the woman’s uterus and to promote healing (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008). Among Orthodox Jewish, Islamic, and Hindu cultures, bleeding is associated with pollution. A woman goes into a ritual bath after bleeding stops before she is able to resume relations with her husband (Lewis, 2003). In some African cultures such as in Ghana and Sierra Leone some women do not resume sexual relations with their husbands until the baby is weaned.

Grief and Loss

Dying and death bring traditions that are meaningful to groups of people for most of their lives (see Chapter 36). When traditional medical measures fail, cultural beliefs and practices that are religious and spiritual become the focus. Societies assign different meanings to death of a child, a young person, and an older adult (Box 9-1). In western cultures with strong future time orientation and in which a child is expected to survive his or her parents, death of a young person is devastating. However, in other cultures, in which infant mortality is very high, the emotional distress over a child’s death is tempered by the reality of the commonly observed risks of growing up. Thus the untimely death of an adult is sometimes mourned more deeply.