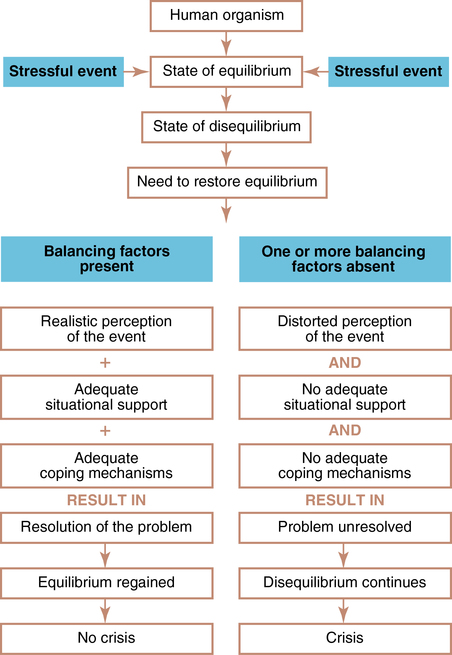

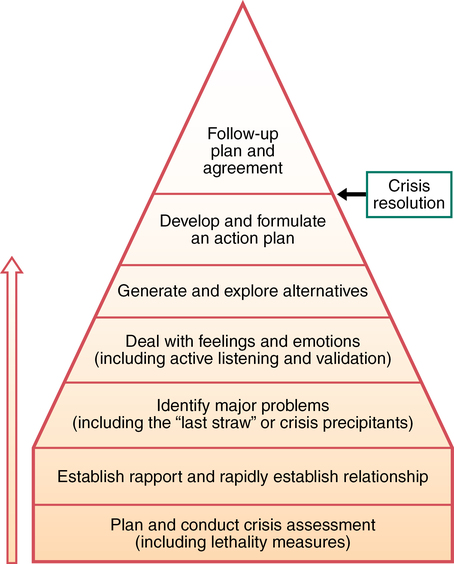

CHAPTER 26 Halter Margaret Jordan and Graor Christine Heifner 1. Differentiate among three types of crisis and provide an example of each. 2. Delineate six aspects of crisis that have relevance for nurses involved in crisis intervention. 3. Develop a handout describing areas to assess during crisis. Include at least two sample questions for each area. 4. Discuss four common problems in the nurse-patient relationship that are frequently encountered by beginning nurses when starting crisis intervention. Discuss two interventions for each problem. 5. Compare and contrast the differences among primary, secondary, and tertiary intervention, including appropriate intervention strategies. 6. Explain to a classmate four potential crisis situations that patients may experience in hospital settings. 7. Provide concrete examples of interventions to minimize the situations. 8. List at least five resources in the community that could be used as referrals for a patient in crisis. 9. Recognize disaster occurrences and management as global concerns. 10. Differentiate among disaster types. 11. Describe three reasons why professional nurses should have disaster-preparedness training. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Crisis is not defined by the experience itself. Crisis is defined by the struggle for equilibrium and adaptation in its aftermath. Roberts (2005) defines a crisis as a profound disruption of a person’s normal psychological homeostasis. Normal coping mechanisms fail to deal with this distress, resulting in an inability to function as usual. The primary cause of crisis is the actual traumatic event, but two other conditions are also involved: The individual perceives the event as significantly distressing. The individual is unable to resolve the disruption by previously used coping mechanisms. As shown in Figure 26-1 (Aguilera, 1998), the outcome of crisis depends on (a) the realistic perception of the event, (b) adequate situational supports, and (c) adequate coping mechanisms. • Perception of the event: People vary in the way they absorb, process, and use information from the environment. Some people may respond to a minor event as if it were life threatening. Conversely, others may assess a life-threatening event and carefully consider options. • Situational supports: Situational supports include nurses and other health professionals who use crisis intervention to assist those in crisis. Crisis intervention is “a short-term therapeutic process that focuses on the rapid resolution of an immediate crisis or emergency using available personnel, family, and/or environmental resources” (American Psychiatric Nurses Association [APNA], 2007, p. 65). • Coping mechanisms: Coping mechanisms and skills are acquired through a variety of sources, such as cultural responses, the modeling behaviors of others, and life opportunities that broaden experience and promote the adaptive development of new coping responses (Aguilera, 1998). Many factors compromise a person’s ability to cope with a crisis event. These may include the number of other stressful life events with which the person is currently coping, other unresolved losses, concurrent psychiatric disorders, concurrent medical problems, excessive fatigue or pain, and the quality and quantity of a person’s usual coping skills. In the early 1960s, Gerald Caplan (1964) advanced crisis theory and outlined crisis intervention strategies. Since that time, our understanding of crisis and effective intervention has continued to be refined and enhanced by numerous contemporary clinicians and theorists (Behrman & Reid, 2002; Roberts, 2005). The 1961 report of the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health addressed the need for community mental health centers throughout the country. This report stimulated the establishment of crisis services, which are now an important part of mental health programs in hospitals and communities. Donna Aguilera and Janice Mesnick (1970) provided a framework for nurses for crisis assessment and intervention, which has grown in scope and practice. Aguilera continues to set a standard in the practice of crisis assessment and intervention. Albert R. Roberts’s seven-stage model of crisis interventions (Figure 26-2) (Roberts, 2005; Roberts & Ottens, 2005) is a model that is useful in helping individuals who have suffered from an acute situational crisis as well as people who are diagnosed with acute stress disorder. In an effort to establish consensus on mass trauma intervention principles, Hobfoll and colleagues (2007) identified five essential, empirically supported elements of mass trauma interventions that promote: (1) a sense of safety, (2) calming, (3) a sense of self-efficacy and collective efficacy, (4) connectedness, and (5) hope. The effects of disasters such as the 9/11 World Trade Center terrorist attack, the earthquake in Haiti in 2010, and a dozen billion-dollar weather disasters in the United States in 2011 have emphasized the need for crisis assessment and intervention by community and general mental health providers. Regardless of the type of crisis and whether traumatized individuals are victims, families, rescue workers, or observers, those with access to crisis assessment and intervention are more likely to feel safe, supported, and empowered. Individuals are also better able to make sense of their response to the disaster, compared to those without access to supportive care providers (Phoenix, 2007). A process of maturation occurs across the life cycle. Erik Erikson (1902-1994) conceptualized the process by identifying eight stages of ego growth and development (see Table 2-2 in Chapter 2). Each stage represents a time when physical, cognitive, instinctual, and sexual changes prompt an internal conflict or crisis, which results in either psychosocial growth or regression. Therefore, each developmental stage represents a maturational crisis that is a critical period of increased vulnerability and, at the same time, heightened potential. A situational crisis arises from events that are extraordinary, external rather than internal, and often unanticipated (Roberts, 2005). Examples of events that can precipitate a situational crisis include the loss or change of a job, the death of a loved one, an abortion, a change in financial status, divorce, and severe physical or mental illness. Whether or not these events precipitate a crisis depends on factors such as the degree of support available from caring friends, family members, and others; general emotional and physical status; and the ability to understand and cope with the meaning of the stressful event. As in all crises or potential crisis situations, the stressful event involves loss or change that threatens a person’s self-concept and self-esteem. To varying degrees, successful resolution of a crisis depends on resolution of the grief associated with the loss. Nurses, perhaps more than any other group of health professionals, deal with people who are experiencing disruption in their lives. Because people typically experience increased stress and anxiety in medical, surgical, and psychiatric hospital settings, as well as in community settings, nurses are often positioned and primed to initiate and participate in crisis intervention. Crisis theory defines aspects of crisis that are basic to crisis intervention and relevant for nurses (Box 26-1). As shown in Figure 26-1, a person’s equilibrium may be adversely affected by one or more of the following: (1) an unrealistic perception of the precipitating event, (2) inadequate situational supports, and (3) inadequate coping mechanisms (Aguilera, 1998). It is crucial to assess these factors when a crisis situation is evaluated because data gained from the assessment guide both the nurse and the patient in setting realistic and meaningful goals and in planning possible solutions to the problem situation. The nurse’s initial task is to promote a sense of safety by assessing the patient’s potential for suicide or homicide. If the patient is suicidal, homicidal, or unable to take care of personal needs, hospitalization should be considered (Aguilera, 1998). Sample questions to ask include the following: • Do you feel you can keep yourself safe? • Have you thought of killing yourself or someone else? If yes, have you thought of how you would do this? • Has anything particularly upsetting happened to you within the past few days or weeks? • What was happening in your life before you started to feel this way? • What leads you to seek help now? • Describe how you are feeling right now. • How does this situation affect your life? • How do you see this event affecting your future? • Who can you talk with when you feel overwhelmed? • Who is available to help you? • How important is spirituality in your life? • Do you take part in organized religious services? • Where do you go to school or to other community-based activities? • During difficult times in the past, whom did you want most to help you? 1. The nurse needs to be needed. 2. The nurse sets unrealistic goals for patients. 3. The nurse has difficulty dealing with the issue of suicide. 4. The nurse has difficulty terminating the nurse-patient relationship. Table 26-1 gives examples, results, appropriate interventions, and desired outcomes of common problems in the nurse-patient relationship faced by beginning nurses. It is crucial that expert supervision be available as an integral part of the crisis-intervention training process. TABLE 26-1 COMMON PROBLEMS IN THE NURSE-PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

Crisis and disaster

Crisis theory

Types of crisis

Maturational crisis

Situational crisis

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

General assessment

Assessing perception of precipitating event

Self-assessment

EXAMPLE

RESULT

INTERVENTION

OUTCOME

Problem 1: Nurse Needs to Feel Needed

Nurse:

Allows excessive phone calls between sessions.

Gives direct advice without sufficient knowledge of patient’s situation.

Attempts to influence patient’s lifestyle on a judgmental basis.

Patient becomes dependent on nurse and relies less on own abilities.

Nurse reacts to patient’s not getting “cured” by projecting feelings of frustration and anger onto patient.

Nurse:

Evaluates personal needs versus patient’s needs with an experienced professional.

Discourages patient’s dependency.

Encourages goal setting and problem solving by patient.

Takes control only if patient is suicidal or homicidal.

Patient is free to grow and problem-solve own life crises.

Nurse’s skills and effectiveness grow as comfort with role increases and own goals are clarified.

Problem 2: Nurse Sets Unrealistic Goals for Patients

Nurse:

Expects physically abused woman to leave battering partner.

Expects man who abuses alcohol to stop drinking when loss of family or job is imminent.

Nurse feels anxious and responsible when expectations are not met; anxiety resulting from feelings of inadequacy are projected onto the patient in the form of frustration and anger.

Nurse:

Examines realistic expectations of self and patient with an experienced professional.

Reevaluates patient’s level of functioning and works with patient on his level.

Encourages setting of goals by patient.

Patient feels less alienated, and a working relationship can ensue.

Nurse’s ability to assess and problem solve increases as anger and frustration decrease.

Problem 3: Nurse Has Difficulty Dealing with a Suicidal Patient

Nurse is selectively inattentive by:

Denying possible clues.

Neglecting to follow up on verbal suicide clues.

Changing topic to less threatening subject when self-destructive themes come up.

Patient is robbed of opportunity to share feelings and find alternatives to intolerable situation.

Patient remains suicidal.

Nurse’s crisis intervention ceases to be effective.

Nurse:

Assesses own feelings and anxieties with help of an experienced professional.

Evaluates all clues or slight suspicions and acts on them (e.g., “Are you thinking of killing yourself?”—if yes, nurse assesses suicide potential and need for hospitalization).

Patient experiences relief in sharing feelings and evaluating alternatives.

Suicide potential can be minimized.

Nurse becomes more adept at picking up clues and minimizing suicide potential.

Problem 4: Nurse has Difficulty Terminating after Crisis Has Resolved

Nurse is tempted to work on other problems in patient’s life to prolong contact with patient.

Nurse steps into territory of traditional therapy without proper training or experience.

Nurse works with an experienced professional to:

Explore own feelings about separations and termination.

Reinforce crisis model; crisis intervention is a preventive tool, not psychotherapy.

Nurse becomes better able to help patient with his/her feelings when nurse’s own feelings are recognized.

Patient is free to go back to his or her life situation or request appropriate referral to work on other issues of importance to patient. ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Crisis and disaster

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access