Continuum of Care

Many patients leave the hospital with ongoing medical (or mental health) needs, and they need a health care continuum that works…treating the whole person from wellness to illness to recovery, within the community.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Explain the meaning of the phrases continuum of care and managed care.

Differentiate the roles of the utilization review nurse, quality assurance nurse, and discharge planner.

Identify the implications of managed care for both psychiatric clients and nurses.

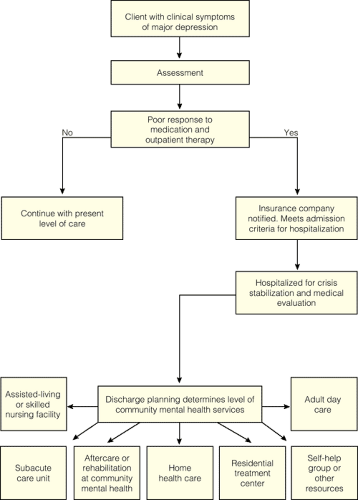

Construct the continuum of care available to a client with the diagnosis of major depression.

Articulate how the components of community-based health care compare with those of community mental health.

Identify the types of community mental health services that are available to psychiatric clients.

Analyze the role of the community mental health nurse.

Key Terms

Case management

Community-based health care

Community mental health

Community Mental Health Centers Act

Continuum of care

Cybertherapy

Deinstitutionalization

Discharge planner

Managed care

National Mental Health Act

Nurse case manager

Programs for Assertive Community Treatment (PACT)

Pre-admission Screening and Annual Resident Review (PASARR)

Prospective payment system (PPS)

Quality assurance nurse

Subacute care unit

Utilization review nurse

Communities provide different types of treatment programs and services for clients with illnesses, including psychiatric–mental health disorders. A complete range of programs and services that treats the whole person from wellness to illness to recovery within the community is called the continuum of care (Green & Lydon, 1998). However, not every community has every type of service or program on the continuum.

The continuum of care is designed to meet the biopsychosocial needs of a client at any given time. The delivery of such services has been referred to as community-based health care. Hunt (1998) defined the following essential components of community-based care: enhancement of client self-care abilities; preventive care; planning care within the context of the client’s family, culture, and community; and collaboration among a diverse team of professionals (Fig. 8-1). Community mental health (discussed later in this chapter) is an example of one aspect of this integrated system that uses a variety of settings and disciplines to provide comprehensive, holistic health care.

This chapter focuses on the continuum of care available to clients as they progress from the most restrictive clinical setting (inpatient) to the least restrictive clinical setting in which they may reside. Trends affecting delivery of care, such as case management, managed care, prospective payment system, and the Mental Health Parity Act, are addressed (Box 8-1). The concept and history of community mental health is also described extensively.

Inpatient Care

Acute care facilities including psychiatric hospitals and subacute units are considered to be the most restrictive clinical settings in which mental health services are available. Although long-term care facilities provide 24-hour inpatient care, outpatient mental health services may be an option if a client is medically stable and able to be transported to a community center for psychiatric services.

Acute Care Facilities

The continuum of care begins in the acute care facility. Examples of different acute care facilities in which psychiatric care may originate include the medical–psychiatric unit of a hospital, transitional-care hospital,

freestanding psychiatric hospital, community-based psychiatric hospital, or forensic hospital.

freestanding psychiatric hospital, community-based psychiatric hospital, or forensic hospital.

Box 8.1: Trends Affecting Delivery of Care

Case Management: The method used to achieve managed care by coordinating services required to meet the needs of a client. Nurses are used in this role.

Managed Care: A system, financed by insurance companies, that controls the balance between cost and quality of care (cost containment). Health care providers are reimbursed for criteria-driven services received by consumers. Examples include health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and preferred provider organizations (PPOs).

Prospective Payment System: A per diem payment system, mandated by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, that covers all costs (routine, ancillary, and capital) related to services where Medicare Part A is the payer. For additional information, visit the Health Care Financing Administration’s website at www.hcfa.gov.

The Mental Health Parity Act: Effective January 1, 1998, it requires equal insurance coverage for mental illness in business health plans.

As a result of the tremendous pressure being exerted on health care to control costs, the average length of client stay in a psychiatric hospital has been dramatically shortened from the standard of the last decade. In the past, it was not unusual for a client to remain hospitalized for several weeks or months until clinical symptoms were considered to be stabilized.

Because hospitalization length of stay has been limited, most clients undergo crisis stabilization and then are transitioned or discharged to a less restrictive environment. To ease the transition, case management is used. The nurse case manager coordinates the continuum of care and determines the providers of care for a particular condition—such as depression—during the transition process. The nurse case manager may assume three different roles: utilization review nurse/manager, quality assurance nurse/manager, and discharge nurse/planner. In today’s health care climate, the utilization review nurse is responsible for monitoring a client’s care to ensure that it is appropriate and given in a timely manner. Utilization review nurses working for insurance companies or health care maintenance organizations determine whether a client’s clinical symptoms meet the appropriate psychiatric or medical necessity criteria or clinical guidelines, as developed by the company and organization. If admission criteria for psychiatric hospitalization are met, a specific amount of time, such as 3 or 5 days, is approved or certified by the insurance provider. If the client requires additional time, the attending clinician must request re-certification. The quality assurance nurse is accountable for the overall quality of care being delivered and often serves as a member of the risk management team, investigating any legal issues that may develop during the client’s hospitalization. The nurse who serves as a discharge planner coordinates all the facets of a client’s admission and discharge. The discharge planner reviews the client’s current response to treatment, past medical history, and assesses what family or friend support is available once the client is ready to be discharged. This concept is referred to as managed care (Shay, 2005).

The per diem prospective payment system (PPS) by Medicare is also a form of managed care. It governs payment for treatment by setting forth specific criteria. The per diem rate covers all costs related to services provided and is based on client need and resources used. For psychiatric treatment, this system applies in general hospitals, subacute or transitional care units, long-term care facilities, or psychiatric facilities where Medicare Part A is the payer. (Part B applies to outpatient treatment or consultant services.) Consequently, the case manager’s position is a mix of clinical and financial responsibilities that are intended to reduce costs and improve outcomes (Joers, 2001; Patterson, 2002). Case management is also utilized to prevent hospitalization. For example, specially trained individuals coordinate or provide psychiatric, financial, legal, and medical services to help a child, adolescent, or adult client live successfully at home and in the community.

As clients transition to less restrictive clinical settings, nurses are challenged to assess the client’s psychiatric and medical needs accurately while developing a therapeutic plan of care, all within a short period of time. Limited time also is available for client and family education. The plan of care must be reviewed by the multidisciplinary treatment team to ensure comprehensive care in the context of environmental, psychosocial, medical, financial, and functional issues after discharge (Green & Lydon, 1998). Where the client goes after leaving the psychiatric hospital depends on the care needed, available social support systems, and his or her insurance coverage. For instance, the client’s freedom to select a clinician or therapist may be limited because the insurance company or health care maintenance organization establishes working relationships and contracts with preferred providers.

The continuum of care may continue in subacute care units, transitional care units, assisted-living or skilled nursing facilities, or adult day care, or may be part of home health care, as depicted in Figure 8-2 (Tellis-Nayak, 1998).

Subacute Care Units

Hospitalized clients with psychiatric problems may be transferred to subacute care units, which are generally located in long-term care facilities. These units provide time-limited, goal-oriented care for clients who do not meet the criteria for continued hospitalization. For example, a client with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder who is recovering from open reduction and internal fixation of a fractured hip requires rehabilitation prior to weight bearing. Both medical and psychiatric needs can be met in the subacute care unit. Such units have also been referred to as postacute care units or “rehab units.”

Clinical nurse specialists, nurse practitioners, or psychiatric liaison nurses have been used in the subacute setting to ensure continuum of care while medical needs are addressed and to assist with discharge planning. Length of stay and services provided are generally dictated by criteria developed by insurance providers or Medicare.

Nurses may be confronted with culture shock as they apply subacute care skills to clients. Endless paperwork, such as long assessment forms and documentation

necessary to comply with various guidelines, rules, and regulations, can result in frustration. The psychosocial needs of clients may go unnoticed or unmet if task-oriented procedures take precedence.

necessary to comply with various guidelines, rules, and regulations, can result in frustration. The psychosocial needs of clients may go unnoticed or unmet if task-oriented procedures take precedence.

Long-Term Care Facilities

Over the last decade, the long-term care environment has changed rapidly due to the establishment of subacute and rehabilitation units within long-term care (LTC) facilities. The average client can be admitted to the LTC facility for short-term rehabilitation, behavioral problems, some chronic care issues, or respite care. Today, most clients go home for services that were once provided in LTC facilities. As a result, the clients that are admitted to LTC facilities have more complex conditions or multiple problems. The prevalence of admitted clients with a dual medical and psychiatric disorder has increased as a result of these changes. Frequently seen comorbid psychiatric diagnoses include dementia, delirium, organic anxiety disorder, mood disorder, and adjustment disorder.

Clients with psychosocial needs may be admitted from a general hospital or from home, or they may be transferred from another LTC facility. Direct admissions may also occur from psychiatric hospitals or community mental health centers (CMHCs) after clinical symptoms are stabilized and continuum of care is necessary. For example, a 45-year-old female client with multiple sclerosis is admitted to a psychiatric facility to stabilize clinical symptoms of schizophrenia, paranoid type. The Department of Children and Family Services requests protective services after psychiatric care because of inadequate living conditions in her home. Discharge plans include placement in an LTC facility until alternate living conditions can be arranged.

Federal legislation and evolving regulations shape the delivery of services. The Nursing Home Reform Act of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 set forth guidelines regarding the admission of persons who have psychiatric disorders into LTC facilities. All nursing home applicants are required to be given a preadmission screening test, referred to as Level 1 Pre-Admission Screening and Annual Resident Review (PASARR), to determine the presence or absence of a serious mental illness. If a client does meet the criteria for a serious mental illness (excluding dementia or organic brain disorders), state mental health authorities must provide mental health services or arrange for these services to be provided in the LTC facility. Mental health services may be provided in nursing home facilities by clinicians who have a contractual agreement with the facility, unless the disorder requires specialized services such as substance abuse counseling, electroshock therapy, or intense individual or group psychotherapy (Kaplan, 2001).

In response to these guidelines, psychiatric and psychological services are now provided in most LTC facilities. Nurse practitioners working in collaboration with physicians or psychiatrists are reimbursed for services, which may include consultation or diagnostic interview, follow-up visits to monitor response to medication, brief individual psychotherapy, full individual psychotherapy, group psychotherapy, family psychotherapy, and consultation with family and the medical staff. The clients most in need of admission into LTC facilities often are those who also have the greatest need for psychiatric services. For example, clients may exhibit anxiety or depression resulting from relocation or loss, delirium caused by adverse effects of medication or a medical problem (eg, a urinary tract infection), or behavioral disturbances as a result of an alteration in mental status. The attending clinician often requests a psychiatric consultation or evaluation to determine the cause of the change in mental status, mood, or behavior.

Community Mental Health

Community mental health can best be described as a movement, an ideology, or a perspective that promotes early comprehensive mental health treatment in the community, accessible to all, including children and adolescents. It derives its values, beliefs, knowledge and practices from the behavioral and social sciences (Panzetta, 1985). According to the Surgeon General and community-based mental health studies, fewer than one half of children and youth meeting the diagnostic criteria for emotional or behavioral problems have received community mental health care; therefore, multiple levels of intervention are central to a public health approach to mental health services (Imperio, 2001).

Mental health services provided in the community may include emergency psychiatric care and crisis intervention, partial hospitalization and day-treatment programs, case management, community-based residential treatment programs, aftercare and rehabilitation, consultation and support, and psychiatric home care. The primary goal of community mental health is

to deliver comprehensive care by a professional multidisciplinary team using innovative treatment approaches. Miller (1981) describes five major ideological beliefs influencing community mental health:

to deliver comprehensive care by a professional multidisciplinary team using innovative treatment approaches. Miller (1981) describes five major ideological beliefs influencing community mental health:

Involvement and concern with the total community population

Emphasis on primary prevention

Orientation toward social treatment goals

Comprehensive continuity of care

Belief that community mental health should involve total citizen participation in need determination, policy establishment, service delivery, and evaluation of programs

Historical Development of Community Mental Health

The community mental health movement, often considered to be the third revolution in psychiatry (after the mental hygiene movement in 1908 and the development of psychopharmacology in the 1950s), gained prominence in the early 1960s. Before this time, psychiatric treatment had occurred primarily in psychiatric institutions or psychiatric hospitals. Three very early community programs included a farm program established in New Hampshire in 1855, a cottage plan in Illinois in 1877, and community boarding homes for clients who were discharged from state psychiatric hospitals in Massachusetts in 1885. Although successful, these initial efforts were limited until after World War II, when social, economic, and political factors were favorable to stimulate the community mental health movement.

In 1946, the National Mental Health Act provided funding for states to develop mental health programs outside of state psychiatric hospitals. This act also provided funding for the establishment of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in 1949. Early in 1952, an international committee from the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the components of community mental health as outpatient treatment, rehabilitation, and partial hospitalization. Later in the decade, state- and federally funded programs mandated the broadening of services to include 24-hour emergency walk-in services, community clinics for state hospital clients, traveling mental health clinics, community vocational rehabilitation programs, halfway houses, and night and weekend hospitals.

In October 1963, U.S. President John F. Kennedy, who supported the improvement of mental health care, approved major legislation significantly strengthening community mental health. This legislation, the Community Mental Health Centers Act, authorized the nationwide development of CMHCs to be established outside of hospitals in the least restrictive setting in the community. It was believed that these centers would provide more effective and comprehensive mental health treatment than the often remote, state-run hospitals that previously served as the primary setting for psychiatric client care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree