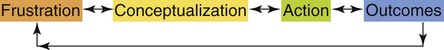

• Use a model of the conflict process to determine the nature and sources of perceived and actual conflict. • Assess preferred approaches to conflict, and commit to be more effective in resolving future conflict. • Determine which of the five approaches to conflict is the most appropriate in potential and actual situations. • Identify conflict-management techniques that will prevent lateral violence from occurring. Conflict is a disagreement in values or beliefs within oneself or between people that causes harm or has the potential to cause harm. Conflict is a catalyst for change and has the ability to stimulate either detrimental or beneficial effects. If properly understood and managed, conflict can lead to positive outcomes and practice environments, but if it is left unattended, it can have a negative impact on both the individual and the organization (Almost, 2006; Morrison, 2008; Vivar, 2006). In professional practice environments, unresolved conflict among nurses is a significant issue resulting in job dissatisfaction, absenteeism, and turnover. Successful organizations are proactive in anticipating the need for conflict resolution and innovative in developing conflict resolution strategies that apply to all members (Behfar, Peterson, Mannix, & Trochim, 2008). Conflict can be a strategic tool when addressed appropriately and can actually deepen and develop human relationships. Some of the first authors on organizational conflict (e.g., Blake & Mouton, 1964; Deutsch, 1973) claimed that a complete resolution of conflict might, in fact, be undesirable because conflict also stimulates growth, creativity, and change. Seminal work on the concept of organizational conflict management suggested conflict was necessary to achieve organizational goals and cohesiveness of employees, facilitate organizational change, and contribute to creative problem solving (Morrison, 2008). Moderate levels of conflict contribute to the quality of ideas generated and foster cohesiveness among team members, contributing to an organization’s success (Almost, 2006). An organization without conflict is characterized by no change; and in contrast, an optimal level of conflict will generate creativity, a problem-solving atmosphere, a strong team spirit, and motivation of its workers (Strack van Schijndel & Burchardi, 2007). The complexity of the healthcare environment compounds the impact that caregiver stress and unresolved conflict has on patient safety. Conflict is inherent in clinical environments in which nursing responsibilities are driven by patient needs that are complex and frequently changing (Siu, Spense Laschinger, & Finegan, 2008). Healthcare providers are exposed to high stress levels from increased demands on an ever-limited and aging workforce, a decrease in available resources, a more acutely ill and underinsured patient population, and a profound period of change in the practice environment (Kelly, 2006). Nurses employed in better care environments report more positive job experiences and fewer concerns about quality care. Positive practice environments and high core self-evaluations (self-esteem, self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability) predicted nurses’ constructive conflict management, and in turn, greater unit effectiveness (Siu et al., 2008). Favorable core self-evaluation was also a predictor of quality leader-staff relationships, empowerment, and job satisfaction for nurse managers (Laschinger, Purdy, & Almost, 2007). Moreover, hospitals with good nurse-physician relations are associated with better nurse and patient outcomes (Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Lake, & Cheney, 2008). An important factor in the successful management of stress and conflict is a better understanding of its context within the practice environment. The diversity of people involved in health care may stimulate conflict, yet the shared goal of meeting patient care needs provides a solid, ethical foundation for conflict resolution (Saltman, O’Dea, & Kidd, 2006). Because nursing remains a predominately female profession, this may contribute to the use of avoidance and accommodation as primary strategies. Emotions of empathy, compassion, and caring should not be suppressed, but neither should assertive communication and behavior. The stereotypical self-sacrificing behavior seen in avoidance and accommodation is strongly supported by the altruistic nature of nursing (Kelly, 2006). Avoidance may be appropriate during times of high stress, but when overused, it threatens the well-being of nurses and retention within the discipline. A major source of organizational conflict stems from strategies that promote more participation and autonomy of staff nurses. Increasingly, nurses are charged with balancing direct patient care with active involvement in the institutional initiatives surrounding quality patient care. Nurses who perceive themselves to work in a positive practice environment that creates a cooperative work context are more likely to report effective conflict-management approaches (Siu et al., 2008). The Magnet Recognition Program® of the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) (2008) identifies interdisciplinary relationships as one of the “Forces of Magnetism” necessary for Magnet™ designation. Specifically, collaborative working relationships within and among the disciplines are valued and must be demonstrated through mutual respect. Magnet™ hospitals must have conflict-management strategies in place and demonstrate effective use, when indicated. The following are other “forces” that are particularly germane to conflict in the practice environment: • Organizational structure (nurses’ involvement in shared decision making) • Management style (nursing leaders create an environment supporting participation, encourage and value feedback, and demonstrate effective communication with staff) • Personnel policies and programs (efforts to promote nurse work/life balance) • Image of nursing (nurses effectively influencing system-wide processes) • Autonomy (nurses’ inclusion in governance leading to job satisfaction, personal fulfillment, and organization success) Conflict proceeds through four stages: frustration, conceptualization, action, and outcomes (Thomas, 1992). The ability to resolve conflicts productively depends on understanding this process (Figure 23-1) and successfully addressing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that form barriers to resolution. As one navigates through the stages of conflict, moving into a subsequent stage may lead to a return to and change in a previous stage. To illustrate, the evening shift of a cardiac step-down unit has been asked to pilot a new hand-off protocol for the next 6 weeks, which stimulates intense emotions because the unit is already inadequately staffed (frustration). Two nurses on the unit interpret this conflict as a battle for control with the nurse educator, and a third nurse thinks it is all about professional standards (conceptualization). A nurse leader/manager facilitates a discussion with the three nurses (action); she listens to the concerns and presents evidence about the potential effectiveness of the new hand-off protocol. All agree that the real conflict comes from a difference in goals or priorities (new conceptualization), which leads to less negative emotion and ends with a much clearer understanding of all the issues (diminished frustration). The nurses agree to pilot the hand-off protocol after their ideas have been incorporated into the plan (outcome). • What is the nature of our differences? • What are the reasons for those differences? • Does our leader endorse ideas or behaviors that add to or diminish the conflict? • Do I need to be mentored by someone, even if that individual is outside my own department or work area, to successfully resolve this conflict? Tangible and intangible consequences result from the actions taken and have significant implications for the work setting. Consequences include (1) the conflict being resolved with a revised approach, (2) stagnation of any current movement, or (3) no future movement. The outcome can be either constructive or destructive; effective strategies minimize destructive effects and maximize constructive outcomes (Saltman et al., 2006). Constructive conflict results in successful resolution, leading to the following: Unsatisfactory resolution is typically destructive and results in the following: • Negativity, resistance, and increased frustration inhibit movement. • Resolutions diminish or are absent. • Groups divide, and relationships weaken. Assessing the degree of conflict resolution is useful for improving individual and group skills in resolutions. Two general outcomes are considered when assessing the degree to which a conflict has been resolved: (1) the degree to which important goals were achieved and (2) the nature of the subsequent relationships among those involved (Box 23-1). Understanding the way healthcare providers respond to conflict is an essential first step in identifying effective strategies to help nurses constructively handle conflicts in the practice environment (Sportsman & Hamilton, 2007). Five distinct approaches can be used in conflict resolution: avoiding, accommodating, competing, compromising, and collaborating (Thomas & Kilmann, 1974, 2002). These approaches can be viewed within two dimensions: assertiveness (satisfying one’s own concerns) and cooperativeness (satisfying the concerns of others). Most people tend to employ a combined set of actions that are appropriately assertive and cooperative, depending on the nature of the conflict situation (Thomas, 1992). See the conflict self-assessment in Box 23-2.

Conflict

The Cutting Edge of Change

Introduction

Types of Conflict

Stages of Conflict

Conceptualization

Outcomes

Modes of Conflict Resolution