Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Objectives

• Differentiate between complementary and alternative therapies.

• Describe the clinical applications of relaxation therapies.

• Discuss the relaxation response and its effect on somatic ailments.

• Identify the principles and effectiveness of imagery, meditation, and breathwork.

• Describe the purpose and principles of biofeedback.

• Describe the methods of and the psychophysiological responses to therapeutic touch.

• Explain the scope of practice of chiropractic therapy.

• Discuss the principles and applications of acupuncture.

Key Terms

Acupoints, p. 650

Acupuncture, p. 649

Allopathic medicine, p. 643

Alternative therapies, p. 644

Biofeedback, p. 649

Chiropractic therapy, p. 650

Complementary therapies, p. 643

Creative visualization, p. 648

Cupping, p. 652

Imagery, p. 648

Integrative health care, p. 644

Integrative health care programs, p. 644

Meditation, p. 648

Meridians, p. 649

Moxibustion, p. 652

Passive relaxation, p. 647

Progressive relaxation, p. 647

Qi gong, p. 652

Relaxation response, p. 646

Stress response, p. 644

Tai chi, p. 652

Therapeutic touch (TT), p. 650

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), p. 651

Vital energy (qi), p. 649

Whole medical systems, p. 644

Yin and yang, p. 651

![]()

The general health of North American people has steadily improved over the course of the last century as evidenced by lower mortality rates and increased life expectancies. Changes in science and medicine have provided the knowledge and technology to successfully alter the course of many illnesses. Despite the success of allopathic medicine (conventional western medicine), many conditions such as chronic back and neck pain, arthritis, gastrointestinal problems, allergies, headache, and anxiety are sometimes difficult to treat. As a result, more patients are exploring alternative methods to relieve their symptoms. Researchers estimate that up to 75% of patients seek care from their primary care practitioners for stress, pain, and health conditions for which there are no known causes or cures (Rakel and Faass, 2006). Although allopathic medicine is quite effective in treating numerous physical ailments (e.g., bacterial infections, structural abnormalities, and acute emergencies), it is generally less effective in decreasing stress-induced illnesses, managing chronic disease, caring for the emotional and spiritual needs of individuals, and improving quality of life and general well-being.

The number of patients seeking unconventional treatments has risen considerably over the past decade. The most recent comprehensive national survey estimates that between 38.3% and 62.1% of the U.S. population uses complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (Barnes et al., 2008). In part this increase is caused by (1) a desire for less invasive, less toxic, “more natural” treatments; (2) lack of satisfaction with allopathic treatments; (3) an increasing desire by patients to take a more active role in their treatment process; (4) beliefs that a combination of treatments (allopathic and complementary) result in better overall results; (5) the increased number of research articles in journals such as Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine and the Journal of Holistic Nursing; and (6) beliefs and values that are consistent with an approach to health that incorporates the mind, body, and spirit or a holistic approach (Koithan, 2009).

Complementary and Alternative Approaches to Health

The National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NIH/NCCAM, 2010b) defines CAM as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.” Complementary therapies are therapies used in addition to conventional treatment recommended by the person’s health care provider. As the name implies, complementary therapies complement conventional treatments. Many of them such as therapeutic touch contain diagnostic and therapeutic methods that require special training. Others such as guided imagery and breathwork are easily learned and applied. Complementary therapies also include relaxation; exercise; massage; reflexology; prayer; biofeedback; hypnotherapy; creative therapies, including art, music, or dance therapy; meditation; chiropractic therapy; and herbs/supplements (Fontaine, 2005). Another term that is used to describe interventions used in this fashion, particularly by licensed health care providers, is integrative therapies (Kreitzer et al., 2009).

Alternative therapies may include the same interventions as complementary therapies; but they become the primary treatment, replacing allopathic medical care. For example, a person with chronic pain uses yoga to encourage flexibility and relaxation at the same time that nonsteroidal antiinflammatory or opioid medications are prescribed. Both sets of interventions are based on conventional pathophysiology and anatomy while acknowledging the mind-body connection that contributes to the physiological pain response. In this case yoga is used as a complementary intervention. However, another patient decides a meditative practice that includes yoga and other lifestyle changes is more helpful than an allopathic approach to chronic pain. This patient studies these practices more deeply, adhering to one of the many schools or traditions, and decides to use these practices as the primary approach to manage chronic pain. In this case yoga is an alternative treatment. Several therapies are always considered alternative because they are based on completely different philosophies and life systems than those used by allopathic medicine. These are identified by NIH/NCCAM as whole medical systems such as traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), Ayurveda, and various forms of traditional or folk medicine. Table 32-1 presents types of complementary and alternative therapies.

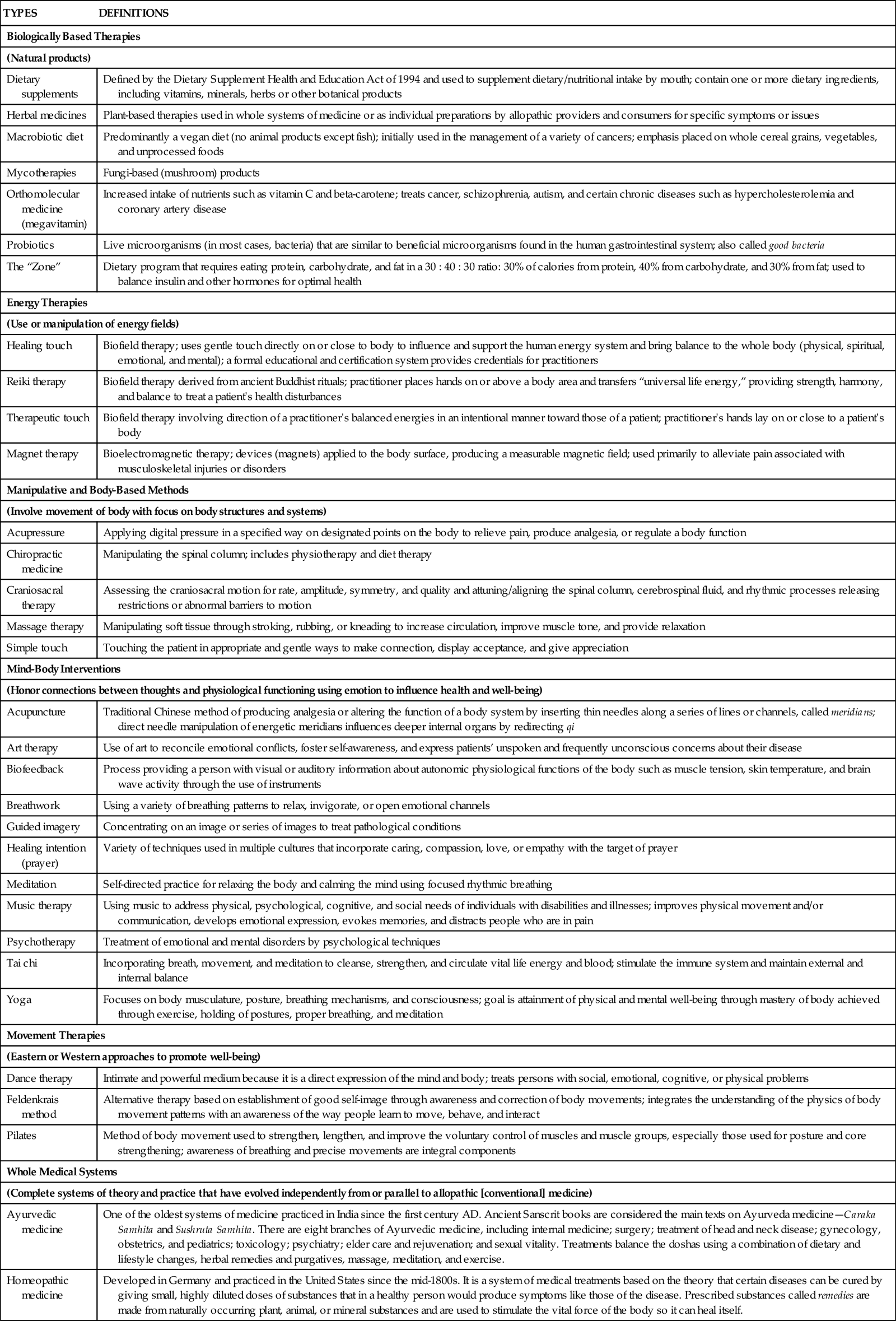

TABLE 32-1

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

| TYPES | DEFINITIONS |

| Biologically Based Therapies | |

| (Natural products) | |

| Dietary supplements | Defined by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 and used to supplement dietary/nutritional intake by mouth; contain one or more dietary ingredients, including vitamins, minerals, herbs or other botanical products |

| Herbal medicines | Plant-based therapies used in whole systems of medicine or as individual preparations by allopathic providers and consumers for specific symptoms or issues |

| Macrobiotic diet | Predominantly a vegan diet (no animal products except fish); initially used in the management of a variety of cancers; emphasis placed on whole cereal grains, vegetables, and unprocessed foods |

| Mycotherapies | Fungi-based (mushroom) products |

| Orthomolecular medicine (megavitamin) | Increased intake of nutrients such as vitamin C and beta-carotene; treats cancer, schizophrenia, autism, and certain chronic diseases such as hypercholesterolemia and coronary artery disease |

| Probiotics | Live microorganisms (in most cases, bacteria) that are similar to beneficial microorganisms found in the human gastrointestinal system; also called good bacteria |

| The “Zone” | Dietary program that requires eating protein, carbohydrate, and fat in a 30 : 40 : 30 ratio: 30% of calories from protein, 40% from carbohydrate, and 30% from fat; used to balance insulin and other hormones for optimal health |

| Energy Therapies | |

| (Use or manipulation of energy fields) | |

| Healing touch | Biofield therapy; uses gentle touch directly on or close to body to influence and support the human energy system and bring balance to the whole body (physical, spiritual, emotional, and mental); a formal educational and certification system provides credentials for practitioners |

| Reiki therapy | Biofield therapy derived from ancient Buddhist rituals; practitioner places hands on or above a body area and transfers “universal life energy,” providing strength, harmony, and balance to treat a patient’s health disturbances |

| Therapeutic touch | Biofield therapy involving direction of a practitioner’s balanced energies in an intentional manner toward those of a patient; practitioner’s hands lay on or close to a patient’s body |

| Magnet therapy | Bioelectromagnetic therapy; devices (magnets) applied to the body surface, producing a measurable magnetic field; used primarily to alleviate pain associated with musculoskeletal injuries or disorders |

| Manipulative and Body-Based Methods | |

| (Involve movement of body with focus on body structures and systems) | |

| Acupressure | Applying digital pressure in a specified way on designated points on the body to relieve pain, produce analgesia, or regulate a body function |

| Chiropractic medicine | Manipulating the spinal column; includes physiotherapy and diet therapy |

| Craniosacral therapy | Assessing the craniosacral motion for rate, amplitude, symmetry, and quality and attuning/aligning the spinal column, cerebrospinal fluid, and rhythmic processes releasing restrictions or abnormal barriers to motion |

| Massage therapy | Manipulating soft tissue through stroking, rubbing, or kneading to increase circulation, improve muscle tone, and provide relaxation |

| Simple touch | Touching the patient in appropriate and gentle ways to make connection, display acceptance, and give appreciation |

| Mind-Body Interventions | |

| (Honor connections between thoughts and physiological functioning using emotion to influence health and well-being) | |

| Acupuncture | Traditional Chinese method of producing analgesia or altering the function of a body system by inserting thin needles along a series of lines or channels, called meridians; direct needle manipulation of energetic meridians influences deeper internal organs by redirecting qi |

| Art therapy | Use of art to reconcile emotional conflicts, foster self-awareness, and express patients’ unspoken and frequently unconscious concerns about their disease |

| Biofeedback | Process providing a person with visual or auditory information about autonomic physiological functions of the body such as muscle tension, skin temperature, and brain wave activity through the use of instruments |

| Breathwork | Using a variety of breathing patterns to relax, invigorate, or open emotional channels |

| Guided imagery | Concentrating on an image or series of images to treat pathological conditions |

| Healing intention (prayer) | Variety of techniques used in multiple cultures that incorporate caring, compassion, love, or empathy with the target of prayer |

| Meditation | Self-directed practice for relaxing the body and calming the mind using focused rhythmic breathing |

| Music therapy | Using music to address physical, psychological, cognitive, and social needs of individuals with disabilities and illnesses; improves physical movement and/or communication, develops emotional expression, evokes memories, and distracts people who are in pain |

| Psychotherapy | Treatment of emotional and mental disorders by psychological techniques |

| Tai chi | Incorporating breath, movement, and meditation to cleanse, strengthen, and circulate vital life energy and blood; stimulate the immune system and maintain external and internal balance |

| Yoga | Focuses on body musculature, posture, breathing mechanisms, and consciousness; goal is attainment of physical and mental well-being through mastery of body achieved through exercise, holding of postures, proper breathing, and meditation |

| Movement Therapies | |

| (Eastern or Western approaches to promote well-being) | |

| Dance therapy | Intimate and powerful medium because it is a direct expression of the mind and body; treats persons with social, emotional, cognitive, or physical problems |

| Feldenkrais method | Alternative therapy based on establishment of good self-image through awareness and correction of body movements; integrates the understanding of the physics of body movement patterns with an awareness of the way people learn to move, behave, and interact |

| Pilates | Method of body movement used to strengthen, lengthen, and improve the voluntary control of muscles and muscle groups, especially those used for posture and core strengthening; awareness of breathing and precise movements are integral components |

| Whole Medical Systems | |

| (Complete systems of theory and practice that have evolved independently from or parallel to allopathic [conventional] medicine) | |

| Ayurvedic medicine | One of the oldest systems of medicine practiced in India since the first century AD. Ancient Sanscrit books are considered the main texts on Ayurveda medicine—Caraka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita. There are eight branches of Ayurvedic medicine, including internal medicine; surgery; treatment of head and neck disease; gynecology, obstetrics, and pediatrics; toxicology; psychiatry; elder care and rejuvenation; and sexual vitality. Treatments balance the doshas using a combination of dietary and lifestyle changes, herbal remedies and purgatives, massage, meditation, and exercise. |

| Homeopathic medicine | Developed in Germany and practiced in the United States since the mid-1800s. It is a system of medical treatments based on the theory that certain diseases can be cured by giving small, highly diluted doses of substances that in a healthy person would produce symptoms like those of the disease. Prescribed substances called remedies are made from naturally occurring plant, animal, or mineral substances and are used to stimulate the vital force of the body so it can heal itself. |

| Latin American traditional healing | Curanderismo is a Latin American traditional healing system that includes a humoral model for classifying food, activity, drugs, and illnesses and a series of folk illnesses. The goal is to create a balance between the patient and his or her environment, thereby sustaining health. |

| Native American traditional healing | Tribal traditions are individualistic, but similarities across traditions include the use of sweating and purging, herbal remedies, and ceremonies in which a shaman (a spiritual healer) makes contact with spirits to ask their direction in bringing healing to people to promote wholeness and healing. |

| Naturopathic medicine | A system of therapeutics focused on treating the whole person and promoting health and well-being rather than an individual disease. Therapeutics include herbal medicine, nutritional supplementation, physical medicine, homeopathy, lifestyle counseling, and mind-body therapies with an orientation toward assisting the person’s internal capacity for self-healing (vitalism). |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | An ancient healing tradition identified in the first century AD focused on balancing yin/yang energies. It is a set of systematic techniques and methods, including acupuncture, herbal medicines, massage, acupressure, moxibustion (use of heat from burning herbs), Qi gong (balancing energy flow through body movement), cupping, and massage. Fundamental concepts are from Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. |

Because of the increased interest in complementary therapies, many institutions, including medical and nursing schools, have training programs that incorporate complementary and alternative therapy content into the curriculum. Some schools have integrative health care programs that allow health care consumers the opportunity to be treated by a team of providers consisting of both allopathic and complementary practitioners. More fully defined, integrative health care emphasizes the importance of the relationship between practitioner and patient; focuses on the whole person; is informed by evidence; and makes use of appropriate therapeutic approaches, health care professionals, and disciplines to achieve optimal health (Kreitzer et al., 2009).

Nurses have historically practiced in an integrative fashion; a review of nursing theory (see Chapter 4) reveals the values of holism, relational care, and informed practice. However, nursing has identified its practice as holistic rather than integrated. Holistic nursing regards and treats the mind-body-spirit of the patient. Nurses use holistic nursing interventions such as relaxation therapy, music therapy, touch therapies, and guided imagery. Such interventions affect the whole person (mind-body-spirit) and are effective, economical, noninvasive, nonpharmacological complements to medical care. Nurses use holistic interventions to augment standard treatments, replace interventions that are ineffective or debilitating, and promote or maintain health (Dossey and Keegan, 2009). The American Holistic Nurses Association maintains Standards of Holistic Nursing Practice, which defines and establishes the scope of holistic practice and describes the level of care expected from a holistic nurse (AHNA/ANA, 2007).

Increasing interest in CAM is evident in the increased number of publications on CAM topics in respected health care journals and the development of new journals that specifically focus on complementary and alternative therapies (e.g., Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Integrative Cancer Therapies). The ongoing mission of the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) supports the investigation of the benefits and safety of CAM interventions. Although the body of evidence about CAM is growing, limited data make it difficult to establish the specific benefits of complementary therapies. Reasons are varied but reflect the growing and developing nature of the science. Therefore nurses should weigh the risk and benefits of each intervention and consider the following when recommending complementary therapies: (1) the history of each therapy (many have been used by cultures for thousands of years to support health and ameliorate suffering); (2) nursing’s history and experience with a particular therapy; (3) other forms of evidence reporting outcomes and safety data, including case study and qualitative research; and (4) the cultural influences and context for certain patient populations.

This chapter discusses several types of complementary and alternative therapies, including a description, the clinical applications, and the limitations of each therapy. The therapies are organized into two categories. The first are nursing-accessible therapies that you can begin to learn and apply in patient care. The second category includes training-specific therapies such as chiropractic therapy or acupressure that a nurse cannot perform without additional training and/or certification.

Nursing-Accessible Therapies

Some complementary therapies and techniques are general in nature and use natural processes (e.g., breathing, thinking and concentration, presence, movement) to help people feel better and cope with both acute and chronic conditions (Box 32-1). You need to learn about these techniques and incorporate them as a part of your independent nursing practice with patients (AHNA/ANA, 2007). Assess your patients and obtain their permission before using complementary therapies. In addition, conduct ongoing outcomes assessment and evaluation of your patients’ responses to the interventions. Sometimes changes to physician-prescribed therapies, such as medication doses, are needed when complementary therapies alter physiological responses and lead to therapeutic responses.

Complementary therapies teach individuals ways in which to change their behavior to alter physical responses to stress and improve symptoms such as muscle tension, gastrointestinal discomfort, pain, or sleep disturbances. Active involvement is a primary principle for these therapies; individuals achieve better responses if they commit to practice the techniques or exercises daily. Therefore to achieve effective outcomes, therapeutic strategies need to be matched with an individual’s lifestyle, his or her beliefs and values, and his or her treatment preferences.

Relaxation Therapy

People face stressful situations in everyday life that evoke the stress response (see Chapter 37). The mind varies the biochemical functions of the major organ systems in response to feedback. Thoughts and feelings influence the production of chemicals (i.e., neurotransmitters, neurohormones, and peptides) that circulate throughout the body and convey messages via cells to various systems within the body. The stress response is a good example of the way in which systems cooperate to protect an individual from harm. Physiologically the cascade of changes associated with the stress response causes increased heart and respiratory rates; tightened muscles; increased metabolic rate; and a general sense of foreboding, fear, nervousness, irritability, and negative mood. Other physiological responses include elevated blood pressure; dilated pupils; stronger cardiac contractions; and increased levels of blood glucose, serum cholesterol, circulating free fatty acids, and triglycerides. Although these responses prepare a person for short-term stress, the effects on the body of long-term stress sometimes include structural damage and chronic illness such as angina, tension headaches, cardiac arrhythmias, pain, ulcers, and atrophy of the immune system organs (Dossey and Keegan, 2009).

The relaxation response is the state of generalized decreased cognitive, physiological, and/or behavioral arousal. Relaxation also involves arousal reduction. The process of relaxation elongates the muscle fibers, reduces the neural impulses sent to the brain, and thus decreases the activity of the brain and other body systems. Decreased heart and respiratory rates, blood pressure, and oxygen consumption and increased alpha brain activity and peripheral skin temperature characterize the relaxation response. The relaxation response occurs through a variety of techniques that incorporate a repetitive mental focus and the adoption of a calm, peaceful attitude (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010).

Relaxation helps individuals develop cognitive skills to reduce the negative ways in which they respond to situations within their environment. Cognitive skills include the following:

The long-term goal of relaxation therapy is for people to continually monitor themselves for indicators of tension and consciously let go and release the tension contained in various body parts.

Progressive relaxation training teaches the individual how to effectively rest and reduces tension in the body. The person learns to detect subtle localized muscle tension sequentially, one muscle group at a time (e.g., the upper arm muscles, the forearm muscles). In doing so the individual learns to differentiate between high-intensity tension (strong fist clenching), very subtle tension, and relaxation (Dossey and Keegan, 2009). He or she practices this activity using different muscle groups. One active progressive relaxation technique involves the use of slow, deep abdominal breathing while tightening and relaxing an ordered succession of muscle groups, focusing on the associated bodily sensations while letting go of extraneous thoughts. When guiding a patient, you may decide to begin with the muscles in the face, followed by those in the arms, hands, abdomen, legs, and feet. Conversely you may also guide a patient to tense and relax muscles, beginning with the feet and working up the body.

The goal of passive relaxation is to still the mind and body intentionally without the need to tighten and relax any particular body part. One effective passive relaxation technique incorporates slow, abdominal breathing exercises while imagining warmth and relaxation flowing through specific body parts such as the lungs or hands. Passive relaxation is useful for persons for whom the effort and energy expenditure of active muscle contracting leads to discomfort or exhaustion.

Clinical Applications of Relaxation Therapy

Research shows relaxation techniques effectively lower blood pressure and heart rate, decrease muscle tension, improve well-being, and reduce symptom distress in persons experiencing a variety of situations (e.g., complications from medical treatments, chronic illness, or loss of a significant other) (Bloch et al., 2010; Kwekkeboom et al., 2008). Research also indicates that relaxation, alone or in combination with imagery, yoga (Fig. 32-1), and music, reduces pain and anxiety while improving well-being (Schmidt et al., 2008; Weeks and Nilsson, 2010). Other benefits of relaxation include the reduction of hypertension (Dickinson et al., 2008), depression (Jorm et al., 2008), and menopausal symptoms, including vasomotor responses, insomnia, mood, and musculoskeletal pain (Innes et al., 2010).

Relaxation enables individuals to exert control over their lives. Some experience a decreased feeling of helplessness and a more positive psychological state overall. Relaxation also reduces workplace stress on nursing units. For example, deep-breathing exercises, centering, and focusing attention often lead to improved staff satisfaction, staff relationships and communication, and workload perceptions (Clarke et al., 2009). Nursing units that incorporate relaxation activities into daily routines experience reduced turnover and improved patient satisfaction scores (Zborowsky and Kreitzer, 2009).

Limitations of Relaxation Therapy

During relaxation training individuals learn to differentiate between low and high levels of muscle tension. During the first months of training sessions, when the person is learning how to focus on body sensations and tensions, there are reports of increased sensitivity in detecting muscle tension. Usually these feelings are minor and resolve as the person continues with the training. However, be aware that on occasion some relaxation techniques result in continued intensification of symptoms or the development of altogether new symptoms (Dossey and Keegan, 2009).

An important consideration when choosing any type of relaxation technique is the physiological and psychological status of the individual. Some patients with advanced disease such as cancer or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) seek relaxation training to reduce their stress response. However, techniques such as active progressive relaxation training require a moderate expenditure of energy, which often increases fatigue and limits an individual’s ability to complete relaxation sessions and practice. Therefore active progressive relaxation is not appropriate for patients with advanced disease or those who have decreased energy reserves. Passive relaxation or guided imagery is more appropriate for these individuals.

Meditation and Breathing

Meditation is any activity that limits stimulus input by directing attention to a single unchanging or repetitive stimulus so the person is able to become more aware of self (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010). It is a general term for a wide range of practices that involve relaxing the body and stilling the mind. The root word, meditari, means to consider or pay attention to something. Although the meditation has its roots in eastern religious practices (Hindu, Buddhism, and Taoism), conventional health care practitioners began to recognize its healing potential in the early 1970s (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010). According to Benson (1975), the four components of meditation are (1) a quiet space, (2) a comfortable position, (3) a receptive attitude, and (4) a focus of attention. He described meditation as a process that anyone can use to calm down; cope with stress; and, for those with spiritual inclinations, feel one with God or the universe.

Meditation is different from relaxation; the purpose of meditation is to become “mindful,” increasing our ability to live freely and escape destructive patterns of negativity. Meditation is self-directed; it does not necessarily require a teacher and can be learned from books or audiotapes (Kabat-Zinn, 2005). Most meditation techniques involve slow, relaxed, deep, abdominal breathing that evokes a restful state, lowers oxygen consumption, reduces respiratory and heart rates, and reduces anxiety (Chiesa and Serretti, 2010).

Clinical Applications of Meditation

Several recent studies support the clinical benefits of meditation. For example, meditation reduces overall systolic and diastolic blood pressures and significantly reduces hypertensive risk (Nidich et al., 2009). It also successfully reduces relapses in alcohol treatment programs (Garland et al., 2010). Patients with cancer who use mindfulness-based cognitive therapies often experience less depression, anxiety, and distress and report an improved quality of life (Foley et al., 2010). Patients suffering from posttraumatic stress disorders and chronic pain also benefit from mindfulness meditation (Kimbrough et al., 2010). In addition, meditation increases productivity, improves mood, increases sense of identity, and lowers irritability (Dossey and Keegan, 2009).

Considerations for the appropriateness of meditation include the person’s degree of self-discipline; it requires ongoing practice to achieve lasting results. Most meditation activities are easy to learn and do not require memorization or particular procedures. Patients typically find mindfulness and meditation self-reinforcing. The peaceful, positive mental state is usually pleasurable and provides an incentive for individuals to continue meditating.

Limitations of Meditation

Although meditation contributes to improvement in a variety of physiological and psychological ailments, it is contraindicated for some people. For example, a person who has a strong fear of losing control will possibly perceive it as a form of mind control and thus will be resistant to learning the technique. Some individuals also become hypertensive during meditation and require a much shorter session than the average 15- to 20-minute session.

Meditation may also increase the effects of certain drugs. Therefore monitor individuals learning meditation closely for physiological changes with respect to their medications. Prolonged practice of meditation techniques sometimes reduces the need for antihypertensive, thyroid-regulating, and psychotropic medications (e.g., antidepressants and anti-anxiety agents). In these cases, adjustment of the medication is necessary.

Imagery

Imagery or visualization is a mind-body therapy that uses the conscious mind to create mental images to stimulate physical changes in the body, improve perceived well-being, and/or enhance self-awareness. Frequently imagery, combined with some form of relaxation training, facilitates the effect of the relaxation technique. Imagery is self-directed, in which individuals create their mental images, or guided, during which a practitioner leads an individual through a particular scenario (Dossey and Keegan, 2009). When guiding an imagery exercise, direct the patient to begin slow abdominal breathing while focusing on the rhythm of breathing. Then direct the patient to visualize a specific image such as ocean waves coming to shore with each inspiration and receding with each exhalation. Next instruct the patient to take notice of the smells, sounds, and temperatures that he or she is experiencing. As the imagery session progresses, instruct the patient to visualize warmth entering the body during inspiration and tension leaving the body during exhalation. Individualize imagery scenarios for each patient to ensure that the image does not evoke negative memories or feelings.

Imagery often evokes powerful psychophysiological responses such as alterations in gastric secretions, body chemistry, internal and superficial blood flow, wound healing, and heart rate/heart rate variability (Pincus and Sheikh, 2009). Although most imagery techniques involve visual images, they also include the auditory, proprioceptive, gustatory, and olfactory senses. An example of this involves visualizing a lemon being sliced in half and squeezing the lemon juice on the tongue. This visualization produces increased salivation as effectively as the actual event. People typically respond to their environment according to the way they perceive it and by their own visualizations and expectancies. Therefore you need to individualize imagery for each patient (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010).

Creative visualization is one form of self-directed imagery that is based on the principle of mind-body connectivity (i.e., every mental image leads to physical or emotional changes) (Gawain, 2008). Box 32-2 lists patient teaching strategies for creative visualization.