Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Complementary or alternative medical (CAM) practices in the United States have grown dramatically in the last decade in popularity. One in every three persons in the United States now resorts to the use of CAM therapy or employs a CAM practitioner to treat a variety of maladies from pain to stress management.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Discuss complementary and alternative medicine therapies as classified by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Differentiate the concepts of curing and healing.

Articulate the components of the holistic model of nursing.

Construct a list of complementary and alternative medicine therapies to treat insomnia, pain, stress and anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline.

Discuss the roles assumed by the client and the holistic nurse during the nursing process.

Identify the importance of client education during the practice of holistic nursing and use of complementary and alternative medicine therapies.

Formulate a set of guidelines to be given to a client receiving complementary and alternative medicine therapy.

Key Terms

Aromatherapy

Cellopathy

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)

Curing

Essential oils

Healing

Holism

Holistic nursing

Homeopathic remedies

Homeopathy

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to various disease-treating and disease-preventing practices or therapies that are not considered to be conventional medicine taught in medical schools, not typically used in hospitals, and not generally reimbursed by insurance companies (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine [NCCAM], 2002). Other terms used to describe these therapeutic approaches include integrative medicine and holistic medicine. During the last 30 years, public interest in the use of CAM systems, approaches, and products has risen steadily. Depending on how CAM is defined, an estimated 6.5% to as much as 43% of the U.S. population has used some form of CAM. Furthermore, it has been estimated that one person in three uses these therapies for clinical symptoms of anxiety, depression, back problems, and headaches. Reasons for this dramatic change include dissatisfaction with increasing health care costs, managed care restrictions, and the focus on management of clinical symptoms rather than etiology (Jancin, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003). As a result of the surge in interest and usage of CAM, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) provided a $50 million budget to support the NCCAM (Jancin, 2000).

Further evidence of the popularity and increasing use of CAM is the addition of such services to benefits packages offered by third-party reimbursement agencies and managed care organizations. This addition is in direct response to the demand by insured clients. Moreover, approximately one half to two thirds of the medical schools in the United States now offer elective courses in CAM therapies such as acupuncture, massage therapy, hypnosis, and relaxation techniques (White, 1999).

In March 2000, the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy (WHCCAMP) was established to address issues related to the practice of CAM. The Commission’s primary task was to provide, through the Secretary of Health and Human Services, legislative and administrative recommendations for ensuring that public policy maximizes the potential benefits of CAM therapies to consumers. The Commission developed 29 recommendations and actions that addressed education and training of health care practitioners in CAM; coordination of research about CAM products; the provision of reliable and useful information on CAM to health care professions; and provision of guidance on the appropriate access to and delivery of CAM (WHCCAMP, 2005). Box 18-1 lists examples of key recommendations by the Commission.

Integrating CAM therapies into nursing practice to treat physiologic, psychological, and spiritual needs requires differentiation of the concepts of curing and healing clients. Curing is described as the alleviation of symptoms or the suppression or termination of a disease process through surgical, chemical, or mechanical intervention. This restoration of function, referred to as cellopathy, reflects the medical model of care. Healing is defined as a gradual or spontaneous awakening that originates within a person and results in a deeper sense of self, effecting profound change. Nurses who integrate CAM into clinical practice and help their clients access their greatest healing potential

practice holistic nursing. This client-oriented approach fits well with the culture of the many CAM therapies used to treat the psychological, spiritual, and physical needs of clients.

practice holistic nursing. This client-oriented approach fits well with the culture of the many CAM therapies used to treat the psychological, spiritual, and physical needs of clients.

Box 18.1: Key Recommendations by White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy (Final Report, 2005)

Federal agencies should receive increased funding for clinical, basic, and health services research on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

Increased efforts should be made to strengthen the emerging dialogue among CAM and conventional medicine practitioners.

Education and training of CAM and conventional medicine practitioners should be designed to ensure public safety, improve health, and increase the availability of qualified and knowledgeable CAM and conventional medicine practitioners to enhance collaboration among them.

Quality and accuracy of CAM information on the Internet should be improved by establishing a voluntary standards board, public education campaigns, and actions to protect consumer privacy.

Information on training and education of providers of CAM services should be accessible to the public.

CAM products should be safe and meet appropriate standards of quality and consistency.

This chapter describes holistic nursing and discusses the common CAM therapies that may be used in the psychiatric–mental health clinical setting. Box 18-2 lists therapies identified by the NIH as appropriate for use with psychiatric–mental health clients.

Box 18.2: Complementary and Alternative Therapies Used in the Psychiatric–Mental Health Clinical Setting

Acupressure: Based on the concept of chi or qi, the essential life force, this Chinese practice uses finger pressure at the same points that are used in acupuncture to balance chi and achieve health.

Acupuncture: Based on the concept of energy fields and chakras (centers in the body located in the pelvis, abdomen, chest, neck, and head), Chinese acupuncture identifies patterns of energy flow and blockage. Hair-thin needles are inserted to either stimulate or sedate selected points going from the head to the feet to correct imbalance of chi or qi.

Aromatherapy: Initially used by Australian aborigines, essential plant oils are used to promote health and well-being by inhalation of their scents or fragrances, essential oil massage, or application of the liquid oil into an electronic infusor, which turns oil into vapor.

Art therapy: Clients are encouraged to express their feelings or emotions by painting, drawing, or sculpting.

Biofeedback: This therapy teaches clients how to control or change aspects of their bodies’ internal environments.

Chinese herbal medicine: An ancient science in modern times, herbs are used to treat a variety of maladies. They may be taken as tea from barks and roots, through the addition of white powders or tinctures to food and juice, or as herbal tonics.

Dance and movement therapy: This therapy enables the client to use the body and various movements for self-expression in a therapeutic environment.

Guided imagery: Clients use consciously chosen positive and healing images to help reduce stressors, to cope with illness, or to promote health.

Homeopathy: Based on the law of “similars,” this system of healing, developed in the 18th century, states that a much-diluted preparation of a substance that can cause symptoms in a healthy person can cure those same symptoms in a sick person. Homeopathic medicines (remedies) are made from plant, animal, and mineral substances and are approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Hypnosis: Hypnosis is used to achieve a relaxed, yet heightened, state of awareness during which clients are more open to suggestion.

Massage therapy: Massage therapy is considered to be a science of muscle relaxation and stress reduction and includes techniques such as healing touch, Rolfing, and Trager therapy.

Meditation: During this therapy, clients sit quietly with eyes closed and focus the mind on a single thought. Chanting or controlled breathing may be used.

Spiritual healing: Spiritual healing addresses the spirit, which is the unifying force of an individual, and may occur as the direct influence of one or more persons on another living system without using known physical means of intervention.

Therapeutic or healing humor: Based on the belief that laughter allows one to experience joy when faced with adversity, therapeutic humor is positive, loving, and uplifting. It connects the usual with the unusual and conveys compassion and understanding. Humor may be found in movies, stories, pantomime, mime, cartoons, and the like.

Therapeutic touch: This therapy is based on the premise that disease reflects a blockage in the flow of energy that surrounds and permeates the body. A four-step process of centering, healing intent, unruffling, and energy transfer occurs as a practitioner attempts to detect and free the blockages.

Holistic Nursing

Holism is a way of viewing health care in terms of patterns and processes instead of medication, technology,

and surgery. Consciousness is considered to be real and influential in illness and wellness. The assessment of thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and attitudes is paramount in the holistic approach. Holistic nursing involves caring for the whole person, and is based on the philosophy that there is an interrelationship among biologic, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of the person. It focuses on searching for patterns and causes of illness, not symptoms; viewing pain and disease as processes that are a part of healing; treating the person as a whole, autonomous client rather than a fragmented, dependent individual; emphasizing the achievement of maximum health and wellness; and equating prevention with wholeness. Holistic nurses use body–mind, spiritual, energetic, and ethical healing (Clark, 1999–2000).

and surgery. Consciousness is considered to be real and influential in illness and wellness. The assessment of thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and attitudes is paramount in the holistic approach. Holistic nursing involves caring for the whole person, and is based on the philosophy that there is an interrelationship among biologic, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of the person. It focuses on searching for patterns and causes of illness, not symptoms; viewing pain and disease as processes that are a part of healing; treating the person as a whole, autonomous client rather than a fragmented, dependent individual; emphasizing the achievement of maximum health and wellness; and equating prevention with wholeness. Holistic nurses use body–mind, spiritual, energetic, and ethical healing (Clark, 1999–2000).

The American Holistic Nurses’ Association (AHNA), established in 1981 by Charlotte McGuire, has developed standards of care that define the discipline of holistic nursing, which has been considered a specialty since 1992 (Box 18-3). A three-tiered program is now available for nurses to obtain national certification through the AHNA. It includes application to qualify for certification, completion of a qualitative assessment of the applicant’s ability to integrate foundation concepts of holistic nursing in one’s life and practice, and the successful completion of a quantitative assessment (ie, national examination). Many alternative medical therapies require certification programs within their scope of practice (Falsafi, 2004). Hospitals across the country are increasingly aware of the importance of holistic nursing and certification for excellence in nursing practice. In hospitals employing certified holistic nurses, there are fewer lawsuits, patients experience fewer complications, and care outcomes are significantly better (Keefe, 2004).

Box 18.3: Summary of the American Holistic Nurses’ Association Core Values of Standards of Care

CORE Value 1. Holistic Philosophy and Education

1.1 Holistic Philosophy: Holistic nurses develop and expand their conceptual framework and overall philosophy in the art and science of holistic nursing to model, practice, teach, and conduct research in the most effective manner possible.

1.2 Holistic Education: Holistic nurses acquire and maintain current knowledge and competency in holistic nursing practice.

CORE Value 2. Holistic Ethics, Theories, and Research

2.1 Holistic Ethics: Holistic nurses hold to a professional ethic of caring and healing that seeks to preserve wholeness and dignity of self, students, colleagues, and the person who is receiving care in all practice settings, be it in health promotion, birthing centers, acute or chronic health care facilities, end-of-life care centers, or in homes.

2.2 Holistic Nursing Theories: Holistic nurses recognize that holistic nursing theories provide the framework for all aspects of holistic nursing practice and transformational leadership.

2.3 Holistic Nursing and Related Research: Holistic nurses provide care and guidance to persons through nursing interventions and holistic therapies consistent with research findings and other sound evidence.

CORE Value 3. Holistic Nurse Self-Care

3.1 Holistic Nurse Self-Care: Holistic nurses engage in self-care and further develop their own personal awareness of being an instrument of healing to better serve self and others.

CORE Value 4. Holistic Communication, Therapeutic Environment, and Cultural Diversity

4.1 Holistic Communication: Holistic nurses engage in holistic communication to ensure that each person experiences the presence of the nurse as authentic and sincere; there is an atmosphere of shared humanness that includes a sense of connectedness and attention reflecting the individual’s uniqueness.

4.2 Therapeutic Environment: Holistic nurses recognize that each person’s environment includes everything that surrounds the individual, both the external and the internal (physical, mental, emotional, social, and spiritual) as well as patterns not yet understood.

4.3 Cultural Diversity: Holistic nurses recognize each person as a whole body–mind–spirit being and mutually create a plan of care consistent with cultural background, health beliefs, sexual orientation, values, and preferences.

CORE Value 5. Holistic Caring Process

5.1 Assessment: Each person is assessed holistically using appropriate traditional and holistic methods while the uniqueness of the person is honored.

5.2 Patterns/Problems/Needs: Actual and potential patterns/problems/needs and life processes related to health, wellness, disease or illness which may or may not facilitate well-being are identified and prioritized.

5.3 Outcomes: Each person’s actual or potential patterns/problems/needs have appropriate outcomes specified.

5.4 Therapeutic Care Plan: Each person engages with the holistic nurses to mutually create an appropriate plan of care that focuses on health promotion, recovery or restoration, or peaceful dying so that the person is as independent as possible.

5.5 Implementation: Each person’s plan of holistic care is prioritized, and holistic nursing interventions are implemented accordingly.

5.6 Evaluation: Each person’s responses to holistic care are regularly and systematically evaluated, and the continuing holistic nature of the healing process is recognized and honored.

Reprinted with permission from the

American Holistic Nurses’ Association. (2000). Summary of AHNA core values. Flagstaff, AZ: Author.

Summary of Holistic Nursing Process

The holistic nurse teaches the client self-assessment skills related to emotional status, nutritional needs, activity level, sleep–wake cycle, rest and relaxation, support systems, and spiritual needs. Nurses need to be aware that clients may self-prescribe herbs or medications for serious underlying physiologic or psychological conditions that have not been previously brought to the attention of a health care provider. If such a situation occurs, the nurse discusses with the client the importance of seeking appropriate medical attention to prevent potential medical complications, adverse reactions to self-prescribed herbs, or adverse herb–drug interactions.

After the client completes self-assessment, problems (diagnoses) are identified, and guidelines are provided to assist the client with problem-solving skills. The client and nurse discuss mutually agreed-on goals and outcomes. For example, suppose the client identifies the problem of overeating related to the inability to express anxiety. The client’s goal may be to develop positive coping skills when experiencing anxiety. Specific outcomes are developed with the client’s input and might include identifying events that contribute to anxiety, reporting which coping skills were used, and reporting fewer episodes of overeating. After the nurse and client agree on goals and outcomes, the client is encouraged to assume responsibility for making these changes. The nurse remains a support, coach, and assessor as the client actively participates in the intervention process. The nurse helps the client by reinforcing self-esteem, confidence, a sense of self-worth, and a positive outlook. Client self-evaluations and subjective comments are used to assess progress toward goals. It is important to remember that the client is a partner in all aspects of the holistic nursing process (Clark, 1999–2000).

Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies in the Psychiatric–Mental Health Setting

Public interest in holistic health care has prompted providers of psychiatric–mental health care to include both traditional and CAM therapies in their practices. Various studies have indicated that 50% of adults and 20% of children are seeing nonphysician practitioners and are availing themselves of CAM (Mulligan, 2003).

The NCCAM defines CAM as those health care and medical practices that are not currently an integral part of conventional medicine. It also notes that CAM practice

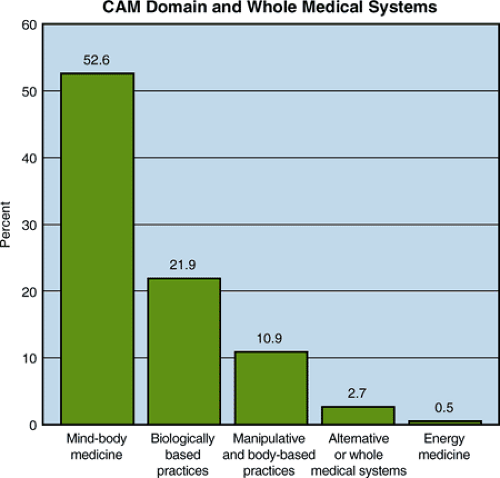

changes continually and that therapies proven safe and effective often become accepted as part of general health care practices (Mulligan, 2003). Although other entities may define CAM and classify interventions differently, the NCCAM divides CAM therapies into five major categories: alternative or whole medical systems, mind–body medicine, biologically based practices, manipulative and body-based practices, and energy medicine (NCCAM, 2002; Poss, 2005). A brief discussion of the more common CAM therapies utilized in the psychiatric–mental health setting follows.

changes continually and that therapies proven safe and effective often become accepted as part of general health care practices (Mulligan, 2003). Although other entities may define CAM and classify interventions differently, the NCCAM divides CAM therapies into five major categories: alternative or whole medical systems, mind–body medicine, biologically based practices, manipulative and body-based practices, and energy medicine (NCCAM, 2002; Poss, 2005). A brief discussion of the more common CAM therapies utilized in the psychiatric–mental health setting follows.

Homeopathy (Alternative Medical System)

Homeopathy, also called vitalism, is classified by the NCCAM as an alternative medical system that evolved independently of and prior to the conventional biomedical approach. (Other examples of alternative or whole medical systems include traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, non-Western cultural medical traditions, and naturopathy.) Homeopathy is a specific healing therapy started in the late 1700s to early 1800s by Samuel Hahnemann, a German physician and chemist. He formulated the theory that the body possesses the power to heal itself. Therefore, a substance creating certain symptoms in a healthy person would cure an ill person exhibiting the same particular set of symptoms. For example, the symptoms of arsenic poisoning include abdominal discomfort, such as stomach cramping with burning pain, nausea, and vomiting. Arsenicum album is a homeopathic remedy used to treat people with symptoms of food poisoning, such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort. The remedy “cancels out” the illness (O’Brien, 2002).

Aromatherapy (Biologically Based Practice)

Aromatherapy, named by the French chemist Maurice René-Maurice Gattefosse in 1928, is classified as a biologically based practice. (Other examples of biologically based practices include herbal, special dietary, orthomolecular, and individual biological therapies.) Aromatherapy is the controlled, therapeutic use of essential oils for specific measurable outcomes. Essential oils are volatile, organic constituents of aromatic plant matter that trigger different nerve centers in the brain to produce specific neurochemicals (Mulligan, 2003).

Mind–Body Medicine

Mind–body medicine includes techniques that assist in the mind’s ability to affect bodily functions and symptoms. Examples of these interventions include meditation, spiritual healing and prayer, and music therapy.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), a form of mind–body medicine, was introduced in 1979 by Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Mindfulness is described as paying nonjudgmental purposeful attention in the present moment of time. Concentration is enhanced by focusing one’s attention on the physical sensations that accompany breathing. Clients are introduced to different forms of MBSR including breathing meditation, body scanning, walking meditation, and hatha yoga. MBSR has proven effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia, anxiety disorders, chronic pain, and recurrent depression. Approximately 240 academic medical centers, hospitals, university health services, and free-standing clinics use the MBSR model (Poss, 2005).

Manipulative and Body-Based Practices

Manipulative and body-based practices include therapies that are applied to improve health and restore function. Examples include Tai Chi, massage therapy, chiropractic treatments, and yoga.

Energy Medicine

Energy medicine includes techniques that focus on energy fields originating in the body (biofields) or from other sources, such as electromagnetic fields. Biofield techniques are said to affect energy fields around the body. Examples include therapeutic touch, healing touch, and Reiki. Bioelectromagnetic-based techniques, which are a form of energy therapy, use electromagnetic fields to treat conditions such as asthma, migraine headaches, or other pain.

Indications for Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapy

Clients in search of low-cost, safe, and effective treatment for clinical symptoms such as insomnia, pain, stress and anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline

have turned to nonpharmaceutical, CAM therapies for symptom relief. Figure 18-1 displays the most frequently used CAM therapies to treat these clinical symptoms.

have turned to nonpharmaceutical, CAM therapies for symptom relief. Figure 18-1 displays the most frequently used CAM therapies to treat these clinical symptoms.

Figure 18.1 Most frequently used categories of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) domain and whole medical systems. |

Information regarding the safety and efficacy of selected herbs discussed in this section is not all-inclusive. Research continues to focus on herb–drug and herb–herb interactions, therapeutic dosages of various herbs, and potential adverse effects of herbal therapy. For example, the American Herbal Products Association has grouped common medicinal herbs into the following four safety classes:

Class 1: Herbs that are considered safe when used appropriately

Class 2: Herbs with specific restrictions for external use only; not to be used during pregnancy; not to be used while nursing; and herbs with other specific restrictions

Class 3: Herbs labeled with instructions that use should occur under supervision of an expert regarding dosage, contraindications, potential adverse effects, drug interactions, and other relevant information related to the safe use of the specific herbal substance

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree