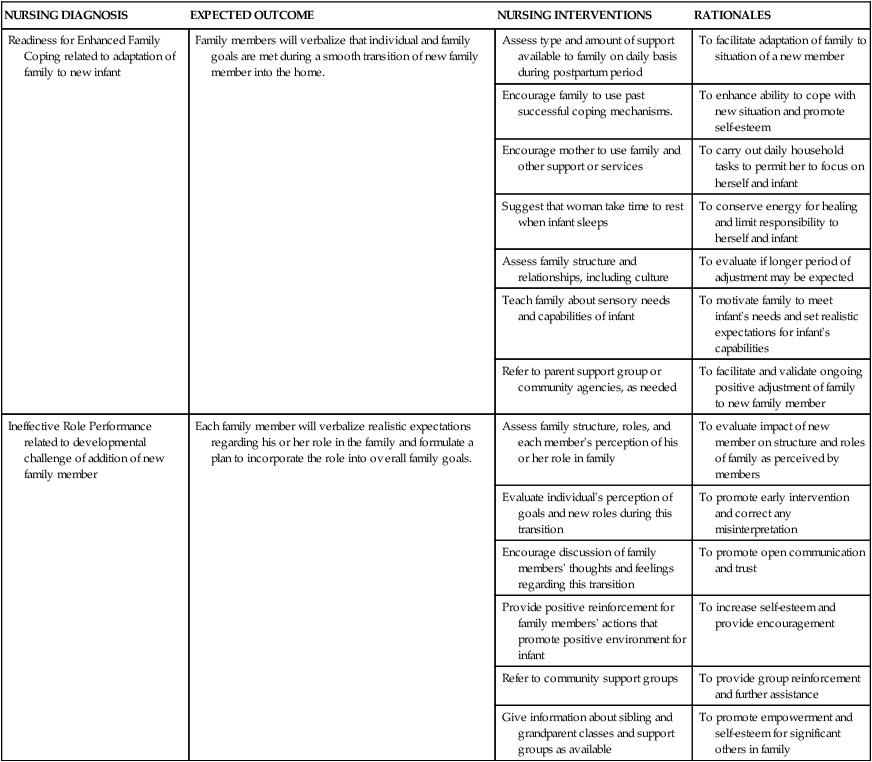

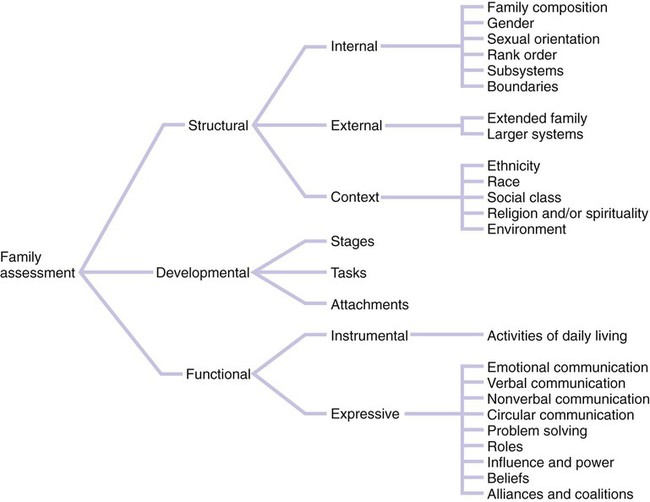

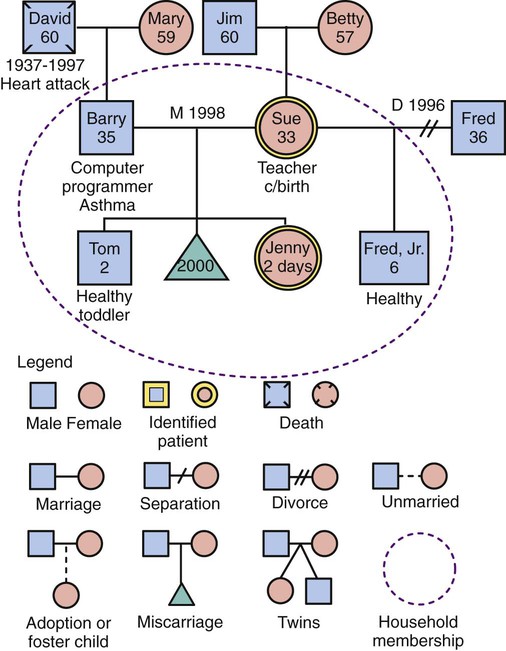

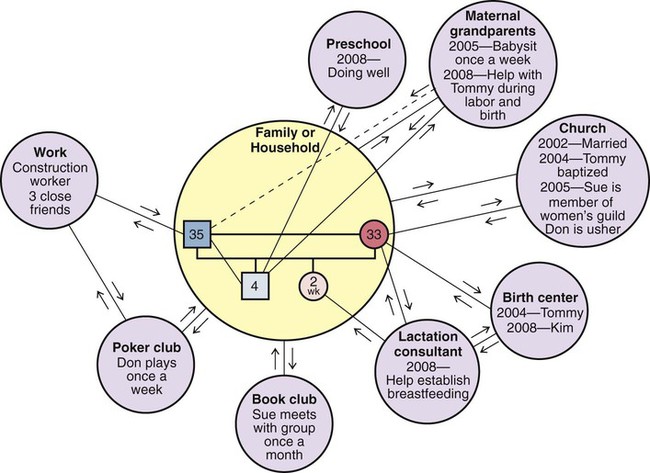

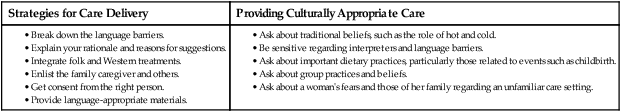

Chapter 2 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the main characteristics of contemporary family forms. • Identify key factors influencing family health. • Compare theoretic approaches for working with childbearing families. • Relate the impact of culture on childbearing families. • Discuss cultural competence in relation to one’s own nursing practice. • Identify key components of the community assessment process. • List indicators of community health status and their relevance to perinatal health. • Describe data sources and methods for obtaining information about community health status. • Identify predisposing factors and characteristics of vulnerable populations. • List the potential advantages and disadvantages of home visits. • Explore telephonic nursing care options in perinatal nursing. • Describe how home fits into the maternity continuum of care. • Discuss safety and infection control principles as they apply to the care of patients in their homes. The nuclear family has long represented the traditional American family in which male and female partners and their children live as an independent unit, sharing roles, responsibilities, and economic resources (Fig. 2-1). In contemporary society, this idealized family structure actually represents only a relatively small number of families, and that number is steadily decreasing. Many nuclear families have other relatives living in the same household. These extended family members include grandparents, aunts, uncles, or other people related by blood (Fig. 2-2). For some groups, such as African-American and Latin-American, extended family is an important resource in terms of preventive health behavior. The extended family is becoming more common as American society ages. Multigenerational families, consisting of grandparents, children, and grandchildren, are becoming increasingly common. In 2010 they made up 4.4% of all households (Lofquist, Lugaila, O’Connell, et al., 2012). This may create stress as children must care for their parents as well as their own children. In other instances, the grandparents are supporting the children and grandchildren or are sole caregivers for the grandchildren. No-parent families are those in which children live independently in foster or kinship care such as living with a grandparent. An estimated 5.4 million children in the United States live with grandparents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Married-parent families (biologic or adoptive parents) make up 48.4% of American families. By race and Hispanic origin, this family structure is represented as follows (Lofquist, Lugaila, O’Connell, et al., 2012): Married-blended families, those formed as a result of divorce and remarriage, consist of unrelated family members (stepparents, stepchildren, and stepsiblings) who join to create a new household. These family groups frequently involve a biologic or adoptive parent whose spouse may or may not have adopted the child. Cohabiting-parent families are those in which children live with two unmarried biologic parents or two adoptive parents. Hispanic children are almost twice as likely as African-American children to live in cohabiting-parent families and about four times as likely as Caucasian children to live in this kind of family arrangement (Lofquist, Lugaila, O’Connell, et al., 2012). Family plays a pivotal role in health care, representing the primary target of health care delivery for maternal and newborn nurses. It is crucial that nurses assist families as they incorporate new additions into their family (see Nursing Care Plan). When treating the woman and family with respect and dignity, health care providers listen to and honor perspectives and choices of the woman and family. They share information with families in ways that are positive, useful, timely, complete, and accurate. The family is supported in participating in the care and decision making at the level of their choice. A family theory can be used to describe families and how the family unit responds to events both within and outside the family. Each family theory makes certain assumptions about the family and has inherent strengths and limitations. Most nurses use a combination of theories in their work with families. A brief synopsis of several theories useful in working with families is included in Table 2-1. Application of these concepts can guide assessment and interventions for the family. TABLE 2-1 THEORIES AND MODELS RELEVANT TO FAMILY NURSING PRACTICE A family assessment tool such as the Calgary Family Assessment Model (CFAM) (Box 2-1) can be used as a guide for assessing aspects of the family. Such an assessment is based on “the nurse’s personal and professional life experiences, beliefs, and relationships with those being interviewed” (Wright and Leahy, 2009) and is not “the truth” about the family but, rather, one perspective at one point in time. The CFAM comprises three major categories: structural, developmental, and functional. Several subcategories are within each category. The three assessment categories and the many subcategories can be conceptualized as a branching diagram (Fig. 2-3). These categories and subcategories can be used to guide the assessment that will provide data to help the nurse better understand the family and formulate a plan of care. The nurse asks questions of family members about themselves to gain understanding of the structure, development, and function of the family at this point in time. Not all questions within the subcategories should be asked at the first interview, and some questions may not be appropriate for all families. Although individuals are the ones interviewed, the focus of the assessment is on interaction of individuals within the family. A family genogram (family tree format depicting relationships of family members over at least three generations) (Fig. 2-4) provides valuable information about a family and can be placed in the nursing care plan for easy access by care providers. An ecomap, a graphic portrayal of social relationships of the woman and family, may also help the nurse understand the social environment of the family and identify support systems available to them (Fig. 2-5). Software is available to generate genograms and ecomaps (www.interpersonaluniverse.net). Assimilation occurs when a cultural group loses its cultural identity and becomes part of the dominant culture. Assimilation is the process by which groups “melt” into the mainstream, thus accounting for the notion of a “melting pot,” a phenomenon that has been said to occur in the United States. This is illustrated by individuals who identify themselves as being of Irish or German descent without having any remaining cultural practices or values linked specifically to that culture such as food preparation techniques, style of dress, or proficiency in the language associated with their reported cultural heritage. Spector (2013) asserts that in the United States, the melting pot, with its dream of a common culture, is a myth. Instead, a mosaic phenomenon exists in which we must accept and appreciate the differences among people. Ethnocentrism is the view that one’s own way of doing things is best (Giger, 2013). Although the United States is a culturally diverse nation, the prevailing practice of health care is based on the beliefs and practices held by members of the dominant culture, primarily Caucasians of European descent. This practice is based on the biomedical model that focuses on curing disease states. Communication often creates the most challenging obstacle for nurses working with patients from diverse cultural groups. Communication is not merely the exchange of words. Instead, it involves (1) understanding the individual’s language, including subtle variations in meaning and distinctive dialects; (2) appreciating individual differences in interpersonal style; and (3) accurately interpreting the volume of speech as well as the meanings of touch and gestures. For example, members of some cultural groups tend to speak more loudly when they are excited, with great emotion and with vigorous and animated gestures; this is true whether their excitement is related to positive or negative events or emotions. It is important, therefore, for the nurse to avoid rushing to judgment regarding a person’s intent when the patient is speaking, especially in a language not understood by the nurse. Instead, the nurse should withhold an interpretation of what has been expressed until it is possible to clarify the patient’s intent. The nurse needs to enlist the assistance of a person who can help verify with the patient the true intent and meaning of the communication (see Critical Thinking Case Study). Inconsistencies between the language of patients and the language of providers present a significant barrier to effective health care. For example, there are many dialects of Spanish that vary by geographic location. Because of the diversity of cultures and languages within the U.S. and Canadian populations, health care agencies are increasingly seeking the services of interpreters (of oral communication from one language to another) or translators (of written words from one language to another) to bridge these gaps and fulfill their obligation for culturally and linguistically appropriate health care (Box 2-2). Finding the best possible interpreter in the circumstance is critically important as well. Ideally, interpreters should have the same native language and be of the same religion or have the same country of origin as the patient. Interpreters should have specific health-related language skills and experience and help bridge the language and cultural barriers between the patient and the health care provider. The person interpreting also should be mature enough to be trusted with private information. However, because the nature of nursing care is not always predictable and because nursing care that is provided in a home or community setting does not always allow expert, experienced, or mature adult interpreters, ideal interpretive services sometimes are impossible to find when they are needed. In crisis or emergency situations or when family members are having extreme stress or emotional upset, it may be necessary to use relatives, neighbors, or children as interpreters. If this situation occurs, the nurse must ensure that the patient is in agreement and comfortable with using the available interpreter to assist. Family roles involve the expectations and behaviors associated with a member’s position in the larger family system (e.g., mother, father, grandparent). Social class and cultural norms also affect these roles, with distinct expectations for men and women clearly determined by social norms. For example, culture may influence whether a man actively participates in pregnancy and childbirth, yet maternity care practitioners working in the Western health care system expect fathers to be involved. This can create a significant conflict between the nurse and the role expectations of very traditional Mexican or Arab families, who usually view the birthing experience as a female affair (see Cultural Competence box). The way that health care practitioners manage such a family’s care molds its experience and perception of the Western health care system. In maternity nursing, the nurse supports and nurtures the beliefs that promote physical or emotional adaptation to childbearing. However, if certain beliefs might be harmful, the nurse should carefully explore them with the woman and use them in the re-education and modification process. Strategies for care delivery and providing appropriate care are presented in Box 2-3. Table 2-2 provides examples of some cultural beliefs and practices surrounding childbearing. The cultural beliefs and customs in the table are categorized on the basis of distinct cultural traditions and are not practiced by all members of the cultural group in every part of the country. Women from these cultural and ethnic groups may adhere to a few, all, or none of the practices listed. In using this table as a guide, the nurse should take care to avoid making stereotypic assumptions about any person based on sociocultural-spiritual affiliations. Nurses should exercise sensitivity in working with every family, being careful to assess the ways in which they apply their own mixture of cultural traditions. TABLE 2-2 TRADITIONAL* CULTURAL BELIEFS AND PRACTICES: CHILDBEARING AND PARENTING

Community Care

The Family and Culture

The Family in Cultural and Community Context

Family Organization and Structure

Theoretic Approaches to Understanding Families

Family Nursing

Family Theories

THEORY

SYNOPSIS OF THEORY

Family Systems Theory (Wright and Leahy, 2009)

The family is viewed as a unit, and interactions among family members are studied rather than studying individuals. A family system is part of a larger suprasystem and is composed of many subsystems. The family as a whole is greater than the sum of its individual members. A change in one family member affects all family members. The family is able to create a balance between change and stability. Family members’ behaviors are best understood from a view of circular rather than linear causality.

Family Life Cycle (Developmental) Theory (Carter and McGoldrick, 1999)

Families move through stages. The family life cycle is the context in which to examine the identity and development of the individual. Relationships among family members go through transitions. Although families have roles and functions, a family’s main value is in relationships that are irreplaceable. The family involves different structures and cultures organized in various ways. Developmental stresses may disrupt the life-cycle process.

Family Stress Theory (Boss, 1996)

How families react to stressful events is the focus. Family stress can be studied within the internal and external contexts in which the family is living. The internal context involves elements that a family can change or control, such as family structure, psychologic defenses, and philosophic values and beliefs. The external context consists of the time and place in which a particular family finds itself and over which the family has no control, such as the culture of the larger society, the time in history, the economic state of society, maturity of the individuals involved, success of the family in coping with stressors, and genetic inheritance.

McGill Model of Nursing (Allen, 1997)

Strength-based approach in clinical practice with families, as opposed to a deficit approach, is the focus. Identification of family strengths and resources; provision of feedback about strengths; assistance given to family to develop and elicit strengths and use resources are key interventions.

Health Belief Model (Becker, 1974; Janz and Becker, 1984)

The goal of the model is to reduce cultural and environmental barriers that interfere with access to health care. Key elements of the Health Belief Model include the following: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and confidence.

Human Developmental Ecology (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; 1989)

Behavior is a function of interaction of traits and abilities with the environment. Major concepts include ecosystem, niches (social roles), adaptive range, and ontogenetic development. Individuals are “embedded in a microsystem [role and relations], a mesosystem [interrelations between two or more settings], an exosystem [external settings that do not include the person], and a macrosystem [culture]” (Klein and White, 1996). Change over time is incorporated in the chronosystem.

Family Assessment

Graphic Representations of Families

The Family in a Cultural Context

Cultural Factors Related to Family Health

Implications for Nursing

Childbearing Beliefs and Practices

Family Roles