Community as Client

Assessment and Analysis

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Decide whether nursing care can be delivered in the community.

3. Discuss the relevance of the nursing process to nursing practice in the community.

4. Analyze the importance of community assessment in nursing practice.

Key Terms

aggregate, p. 398

Assessment Protocol for Excellence in Public Health (APEXPH), p. 405

change agent, p. 417

change partner, p. 417

community, p. 397

community-as-partner model, p. 412

community assessment, p. 406

community competence, p. 401

community health, p. 401

community health problems, p. 411

community health strengths, p. 411

community partnerships, p. 402

community reconnaissance, p. 410

confidentiality, p. 412

database, p. 407

data collection, p. 407

data gathering, p. 407

data generation, p. 409

early adopters, p. 417

empowerment, p. 404

evaluation, p. 418

goals, p. 415

implementation, p. 416

informant interviews, p. 409

interacting groups, p. 417

interdependent, p. 398

intervention activities, p. 416

late adopters, p. 418

lay advisors, p. 417

mass media, p. 418

mediating structures, p. 417

Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP), p. 402

nominal groups, p. 411

objectives, p. 415

participant observation, p. 409

partnership, p. 403

Planned Approach to Community Health (PATCH), p. 405

population-centered practice, pp. 398-399

probability, p. 416

problem analysis, p. 411

problem correlates, p. 411

problem prioritizing, p. 413

program planning model, p. 411

role negotiation, p. 412

secondary analysis, p. 410

surveys, p. 410

target of practice, p. 398

typologies, p. 397

value, p. 416

windshield surveys, p. 409

—See Glossary for definitions

George F. Shuster, RN, DNSc

George F. Shuster, RN, DNSc

Dr. George F. Shuster started as a community volunteer nurse in one of the Seattle Neighborhood Free Clinics in 1981. Since that time, he has practiced as a home-health nurse in San Francisco, California, and later in Charlottesville, Virginia. In Virginia he was involved with the American Lung Association in community-wide smoking cessation programs. In New Mexico he continues to teach public health at the undergraduate and graduate levels and also has been involved in the development of a community-focused health promotion program for older Hispanic women.

Although in the past, nurses have sometimes viewed the community as a client, many nurses have come to consider the community their most important client and, more recently, their partner (Anderson and McFarlane, 2008; Butterfoss, 2009). This chapter clarifies community concepts and provides a guideline for nursing practice with the community client. The core functions of public health nursing (PHN) include assessment, policy development, and assurance. A public and private group partnership called the Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice (2009) has defined competencies for the core functions of public health practice (see Chapter 1 for more details). In the area of assessment, 11 competencies for the nurse and other health providers working in the community are listed (Box 18-1).

The nursing process from assessment through evaluation is used to promote a community’s health. This process begins with community assessment—one of the core functions—which involves getting to know the community. It is a logical, systematic approach to identifying community needs, clarifying problems, and identifying community strengths and resources. This chapter provides the nurse with the knowledge necessary to develop the community assessment core competencies.

Community Defined

Definitions of the meaning of community vary widely. The World Health Organization (WHO) includes this definition: “A group of people, often living in a defined geographical area, who may share a common culture, values and norms, and are arranged in a social structure according to relationships which the community has developed over a period of time. Members of a community gain their personal and social identity by sharing common beliefs, values and norms which have been developed by the community in the past and may be modified in the future” (WHO, 2004, p 16). Other theorists and writers present typologies (lists of types), which involve classifying communities by category rather than single definitions. One such typology of community was described by Blum in 1974. This typology is still used today. The categories, or types of communities, include communities defined by geopolitical boundaries, by their interactions (such as between schools, social services, and governmental agencies), and by their ability to solve problems. Some types of communities are listed in Box 18-2.

Nurses working in communities quickly learn that society consists of many different types of communities. Some of the communities listed in Box 18-2 are communities of place. In this type of community, interactions occur within a specific geographic area. Neighborhood and face-to-face communities are two examples of this type of community. Other communities, such as communities of special interest or resource communities, cut across geographic areas. Common concerns and interests, which can be long term or short term in nature, bring their members together (e.g., a group to support a smoke-free environment). Another type of community is a community of problem ecology, which is created when environmental problems such as water pollution affect a widespread area. For example, a problem such as water pollution can bring people together from areas that would not otherwise share a common interest. Nurses also may work in partnership with communities defined by geographic and political boundaries, such as school districts, townships, or counties. Because the type of community varies, nurses planning community interventions must take into account each community’s specific characteristics. Each community is unique, and its defining characteristics will affect the nature of the partnership.

In most definitions, the community includes three factors: people, place, and function. The people are the community members or residents. Place refers both to geographic and to time dimensions, and function refers to the aims and activities of the community. Nurses regularly need to examine how the people, place, and function dimensions of community shape their nursing practice. They can use both a definition and a set of measures for the community in their practice.

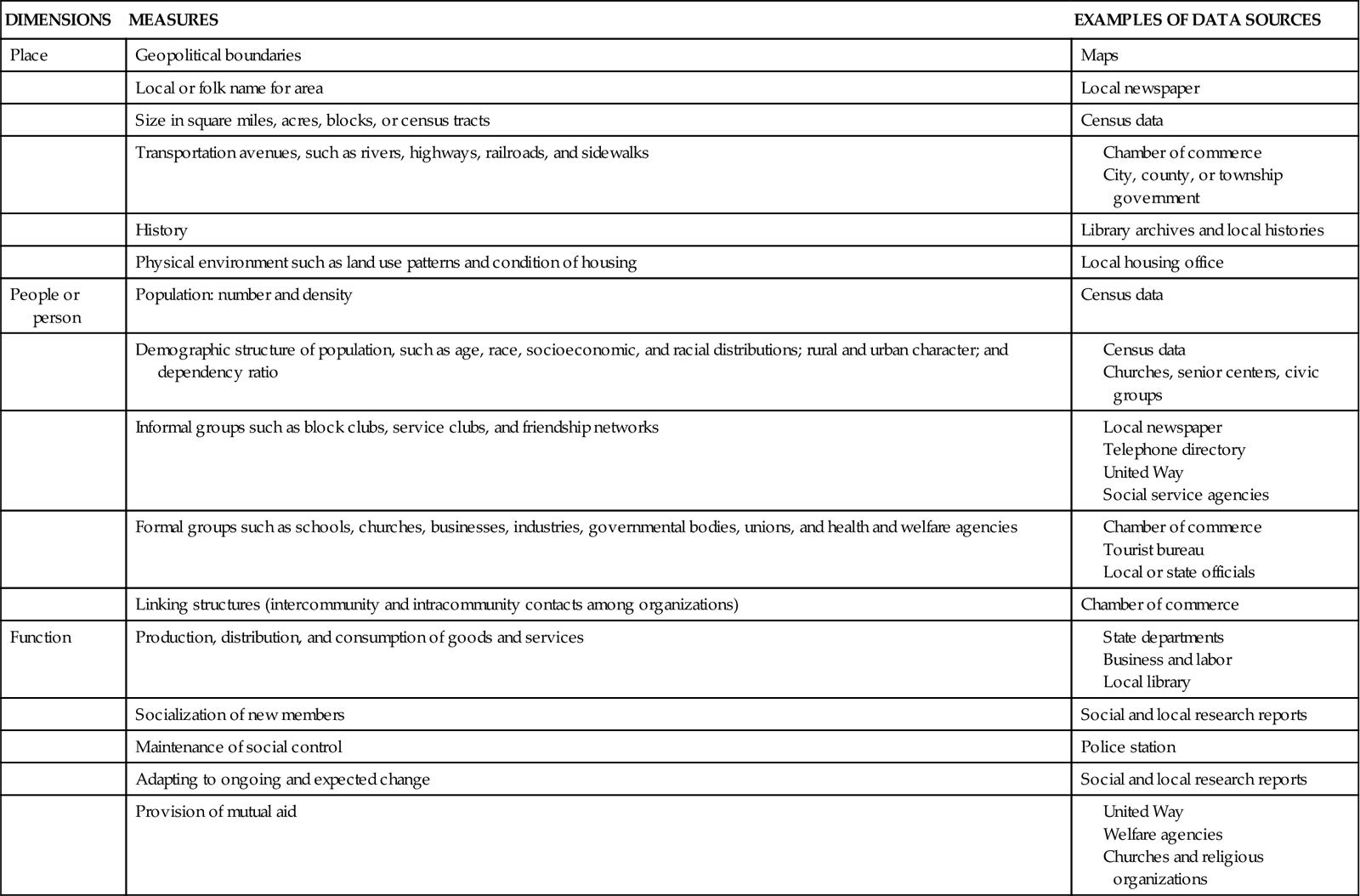

In this chapter, the following definition is used: Community is a locality-based entity, composed of systems of formal organizations reflecting society’s institutions, informal groups, and aggregates. As defined in Chapter 1, an aggregate is a collection of individuals who have in common one or more personal or environmental characteristics. The parts of a community are interdependent, and their function is to meet a wide variety of collective needs. This definition of community includes place and function dimensions and recognizes interaction among the systems within a community. Measures of the dimensions for this definition are listed in Table 18-1.

TABLE 18-1

THE CONCEPT OF COMMUNITY SPECIFIED

If the community is where nurses practice and apply the nursing process, and the community is the client of that practice, then nurses will want to analyze and synthesize information about the boundaries, parts, and dynamic processes of the client community. The next section describes the community as client: it is both the setting for practice and the target of practice (i.e., the client) for the nurse.

Community as Client

Nurses who have a community orientation have often been considered unique because of their target of practice. The idea of health-related care being provided within the community is, however, not new. At the turn of the century, most persons stayed at home during illnesses. As a result, the practice environment for all nurses was the home rather than the hospital. As the range of nursing services expanded into the community, many different kinds of agencies were started, and their services often overlapped. For example, both privately owned voluntary agencies and official or governmental local health agencies worked to control tuberculosis. The nurses employed by these agencies were called community health nurses, public health nurses, and visiting nurses. They practiced in clients’ homes and not in the hospital. Today, these three types of nurses are nurses working to improve the public’s health.

Early PHN textbooks in the 1940s included lengthy descriptions of the home environment and tools for assessing the extent to which that environment promoted the health of family members. Health education about the home environment was often a major part of home nursing care.

By the 1950s, schools, prisons, industries, and neighborhood health centers, as well as homes, had all become settings of practice for nurses. Many of these new nurses did not consider the environments in which they practiced. Although their practices took place within the community, they focused on the individual client or the family seeking care. The care provided was not population centered; rather, it was oriented toward the individual or family who lived in the community, and this is now called community-based nursing practice. This commitment to direct, hands-on, clinical nursing care delivered to individuals or families in community settings remains a more popular approach to nursing practice than recognizing the whole community as the target of nursing practice. This remains true today with the American Public Health Association: Public Health Nursing Section (APHA: PHN) statement that “Public health nurses integrate community involvement and knowledge about the entire population with personal, clinical understandings of the health and illness experiences of individuals and families within the population”(APHA: PHN, 2009, www.apha.org/membersgroups). When the location of the practice is the community and the focus of the practice is the individual or family, the client remains the individual or family, and the nurse is practicing in the community as the setting; this is an example of community based nursing practice.

The community is the client only when the nursing focus is on the collective or common good of the population instead of on individual health. Population-centered practice seeks healthful change for the whole community’s benefit (Radzyminski, 2007). Although the nurse may work with individuals, families or other interacting groups, aggregates, or institutions, or within a population, the resulting changes are intended to affect the whole community. For example, an occupational health nurse’s target might be preventing illness and injury and maintaining or promoting the health of an entire company workforce. Because of this focus, the nurse would help an individual disabled worker become independent in activities of daily living. The nurse would also become involved with promoting vocational rehabilitation services in the community and seek reasonable employment policies for all disabled workers through the community government.

Community Client and Nursing Practice

Population-focused health care is experiencing a rebirth, and the community as client is important to nursing practice for several reasons. When focusing on the community as client, direct clinical care can be a part of population-focused community health practice (Radzyminski, 2007). For example, sometimes direct nursing care is provided to individuals and family members because their health needs are common community-related problems. Changes in their health will affect the health of their communities (O’Donnell et al, 2009).

In such cases, decisions are made at the individual level because the individual’s health is related to the health of the population as a whole. Improved health of the community remains the overall goal of nursing intervention. Interventions to stop spousal or elder abuse are two examples of nursing interventions done primarily because of the effects of abuse on society and therefore on the population as a whole. Also, the treatment of a client for tuberculosis reduces the risk to other community members. This care reduces the risk of an epidemic in the community.

The community client also highlights the complexity of the change process. Change for the benefit of the community client must often occur at several levels, ranging from the individual to society as a whole. For example, health problems caused by lifestyle, such as smoking, overeating, and speeding, cannot be solved simply by asking individuals to choose health-promoting habits. Society must also provide healthy choices. Most individuals cannot change their habits alone; they require the support of family members, friends, community health care systems, and relevant social policies. Individuals who have lifestyle health problems are often blamed for their illness because of their choices (e.g., to smoke). In his classic work, Ryan (1976) points out that the “victim” cannot always be blamed and expected to correct the problem without changes also being made in the helping professions and public policy. Some communities have no-smoking areas in restaurants to prevent second-hand smoke from harming others. This is an example of a community-level policy to change behavior.

Commitment to the health of the community client requires a process of change at each of these levels. One nursing role emphasizes individual and direct personal care skills, another nursing role focuses on the family as the unit of service, and a third focuses on the community as a unit of service. Collaborative practice models involving the community and nurses in joint decision making and specific nursing roles are required (Bencivenga et al, 2008). Ndirangu et al (2008) note that nurses must remember that collaboration means shared roles and a cooperative effort in which participants want to work together. These participants must see themselves as part of a group effort and share in the process, beginning with planning and including decision making. This means sharing not only the power but also the responsibility for the outcomes of the intervention. Viewing the community as client and thus as the target of service means a commitment to two key concepts: (1) community health and (2) partnership for community health. These two concepts form not only the goal (community health), but also the means of population-centered practice (partnership).

Goals and Means Of Practice in The Community

In population-centered practice, the nurse and the community seek healthy change together (Kruger et al, 2010). Their common goal of community health involves an ongoing series of health-promoting changes rather than a fixed state. The most effective means of completing healthy changes in the community is through this same partnership. Specific examples of partnership between the nurse and the community (Bernalillo County) are provided throughout this chapter and in the tables at the end of the chapter.

Community Health

Like the concept of community, community health has three common characteristics, or dimensions: status, structure, and process. Each dimension reflects a unique aspect of community health (Cottrell, 1976).

Status

Community health in terms of status, or outcome, is the most well-known and accepted approach; it involves biological, emotional, and social parts. The biological (or physical) part of community health is often measured by traditional morbidity and mortality rates, life expectancy indexes, and risk factor profiles. The question of exactly which risk factors are most important has been a matter of ongoing disagreement. In an effort to help resolve this question, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (1991) published the work of a consensus committee involving representatives from a number of community health–related organizations. This committee identified by consensus 18 community health status measures and risk factors (Box 18-3). More recently the CDC in partnership with a number of public health organizations has relaunched the Community Health Status Indicators (CHSI) project to provide an overview of key health indicators for local communities such as those identified by the MMWR(1991). Health status indicator data on thousands of communities can be found at http://www.communityhealth.hhs.gov.

The emotional part of health status can be measured by consumer satisfaction and mental health indexes. Crime rates and functional levels reflect the social part of community health. Other status measures, such as worker absenteeism and infant mortality rates, reflect the effects of all three parts.

Structure

Community health, when viewed as the structure of the community, is usually defined in terms of services and resources. Measures of community health services and resources include service use patterns, treatment data from various health agencies, and provider-to-client ratios. These data provide information, such as the number of available hospital beds or the number of emergency department visits to a particular hospital. The problems that can be found when structure measures are used are serious. For example, problems related to access to care and quality of care are well-known through stories reported in local newspapers. Less well-known, but of equal concern, is the false belief that simply providing health care improves health. Such problems require cautious use of health services and resources as measures of community health.

A structural viewpoint also defines the characteristics of the community structure itself. Characteristics of the community structure are commonly identified as social measures, or correlates, of health. Measures of community structure include demographics, such as socioeconomic and racial distributions, age, and educational level. Their relationships to health status have been thoroughly documented. For example, studies have repeatedly shown that health status decreases with age and improves with higher socioeconomic levels.

Process

The view of community health as the process of effective community functioning or problem solving is well established. However, it is especially appropriate to nursing because it directs the study of community health for community action.

Community competence, defined originally in a classic work by Cottrell (1976), provides a basic understanding of the process dimension of community health. Community competence is a process whereby the parts of a community—organizations, groups, and aggregates—“are able to collaborate effectively in identifying the problems and needs of the community; can achieve a working consensus on goals and priorities; can agree on ways and means to implement the agreed-on goals; and can collaborate effectively in the required actions” (Cottrell, 1976, p 197).

The conditions of community competence are listed and defined in Table 18-2. Ruderman (2000) further expanded upon Cottrell’s definition by indicating that community competence indicates the capacity of a community to implement change by assessing the need or the demand for change. Once change is indicated, then the community must define and make available the resources for the change to occur.

TABLE 18-2

THE 10 ESSENTIAL CONDITIONS OF COMMUNITY COMPETENCE

| CONDITION | DEFINITION |

| Commitment | The affective and cognitive attachment to a community “that is worthy of substantial effort to sustain and enhance” (Cottrell, 1976, p 198) |

| Awareness of self and others and clarity of situational definitions | The clear and realistic view of one’s own and other persons’ community components, identities, and positions on issues |

| Articulateness | The technical aspects of formulating and stating one’s views in relation to other persons’ views |

| Effective communication | The accurate transmission of information based on the development of common meaning among the communicators |

| Conflict containment and management of accommodation | The inventive and effective assimilation and management of true or realistically perceived differences |

| Participation | Active, population-centered involvement |

| Management of relations with larger society | Adeptness at recognizing, obtaining, and using external resources and supports and, when necessary, stimulating the creation and use of alternative or supplementary resources |

| Machinery for facilitating participant interaction and decision making | Flexible and responsible procedures (formal and informal), participant interaction and facilities, interaction, and decision making |

| Social support | Perceptions of community competency |

| Leadership development | Degree to which community competence has changed since community organization efforts |

From Cottrell LS: The competent community. In Kaplan BH, Wilson RN, Leighton AH, editors: Further explorations in social psychiatry, New York, 1976, Basic Books; Goeppinger J, Lassiter PG, Wilcox B: Community health is community competence, Nurs Outlook 30:464, 1982.

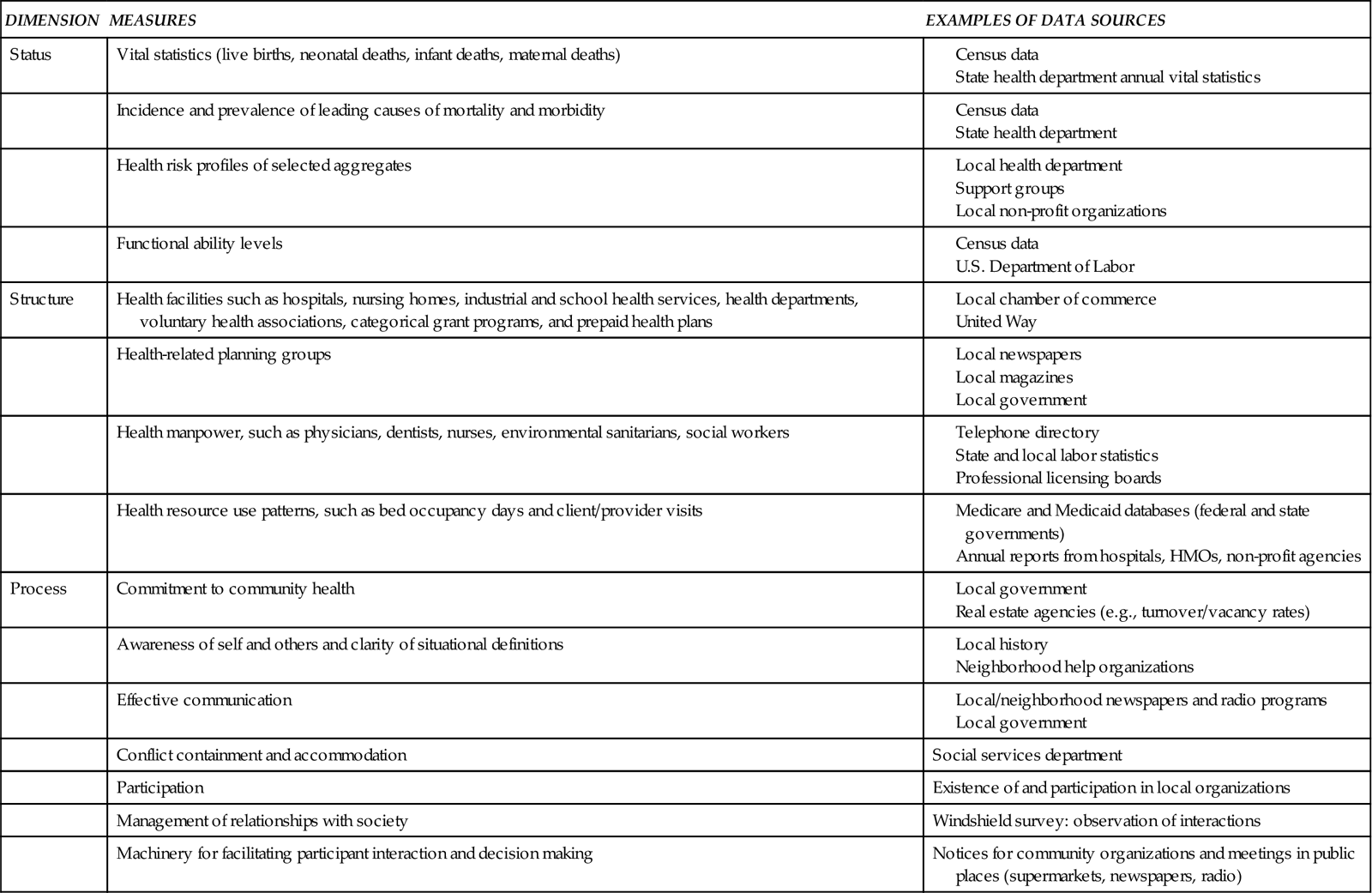

The term community health as used in this chapter is the meeting of collective needs by identifying problems and managing behaviors within the community itself and between the community and the larger society. This definition emphasizes the process dimension but also includes the dimensions of status and structure. Measures for all three dimensions are listed in Table 18-3. The use of status, structure, and process dimensions to define community health, as shown in Table 18-3, is an effort to develop a broad definition of community health, involving measures that are often not included when discussions focus only on risk factors as the basis for community health. Nevertheless, epidemiological data related to health risks of aggregates and populations, commonly expressed as rates and confidence intervals, are vital measures of health status (Goodman et al, 2009).

TABLE 18-3

CONCEPT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH SPECIFIED

Consideration of health risks guides us to think upstream—to identify risks that could be prevented to make and keep people healthy. Most community- and population-oriented approaches to health are grounded in the notion that the earlier in the causal process (or more upstream) interventions occur, the greater the likelihood of improved health. Frequently, prevention or upstream action requires community-wide intervention directed toward social, economic, and environmental conditions that correlate with low health status (Minkler et al, 2008). Examples of such interventions are presented under “Implementing in the Community” later in this chapter.

Healthy People 2020

One important guideline that is available for nurses working to improve the health of the community is Healthy People 2020, a publication from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS, 2010). It offers a vision of the future for public health and specific objectives to help attain that vision. The Healthy People 2020 vision recognizes the need to work collectively, in community partnerships, to bring about the changes that will be necessary to fulfill this vision. Healthy People 2020 provides the foundation for a national health promotion and disease-prevention strategy built on the two goals of increasing the “quality and years of healthy life” and eliminating “health disparities.” In Section IV of the Advisory Committee Findings and Recommendations for The Role and Function of Healthy People 2020, there is direct discussion about the relationship between individuals and their communities. It states, “The Advisory Committee believes Healthy People 2020 can best be described as a national health agenda that communicates a vision and a strategy for the nation. Healthy People 2020 should provide overarching, national-level goals. On a practical level, it is a road map showing where we want to go as a nation and how we are going to get there.” “Indeed, the underlying premise of Healthy People 2020 is that the health of the individual is almost inseparable from the health of the larger community.”

In the section titled, Healthy People 2020: The Road Ahead, the direction for Healthy People 2020 is stated: “The Healthy People process is inclusive; its strength is directly tied to collaboration.” The development process strives to maximize transparency, public input, and stakeholder dialogue to ensure that Healthy People 2020 is relevant to diverse public health needs and seizes opportunities to achieve its goals. This process is inherent for community partnerships, particularly when they reach out to non-traditional partners; these community partnerships can be among the most effective tools for improving health in communities. Because Healthy People 2020 is dynamic rather than static, the Public Health Service (PHS) will continue to review the progress of meeting the goals.

Community Partnerships

The executive summary written by the advisory committee for Healthy People 2020 identifies a model for action that will require community partnership as key to meeting program goals. Community partnership is necessary because when there is a community partnership, lay community members have a vested interest in the success of efforts to improve the health of their community. Lay community members who are recognized as community leaders also possess credibility and skills that health professionals often lack. Therefore, successful strategies for improving community health must include community partnerships as the basic means, or key, for improvement (Adams and Canclini, 2008). Community partnership is a basic focus of such population-centered approaches as Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) (NACCHO, 2008).

Most changes must aim at improving community health through active partnerships between community residents and health workers from a variety of disciplines. Unfortunately, community residents are often viewed only as sources of information and receivers of interventions. This form of partnership is called passive participation. Passive participation is the opposite of the partnership approach in which all are involved in assessing, planning, and implementing needed community changes (Ndirangu et al, 2008; Timmerman, 2007).

The community member–professional partnership approach specifically emphasizes active participation. Power is shared among lay and professional persons throughout the assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation processes. Partnership means the active participation and involvement of the community or its representatives in healthy change (O’Donnell, 2009). For example, breast cancer is an issue for rural Native American women, and an active community partnership involving the Native American women helped develop and ensure an effective, ongoing program (Christopher et al, 2008) (Box 18-4).

Partnership, as defined here, is a concept that is as essential for nurses to know and use as are the concepts of community, community as client, and community health. Experienced nurses know that partnership is important because health is not a static reality. Rather, it is continuously generated through new and increasingly effective means of community member–professional collaboration. However, such changes also require other active professional service providers, such as school teachers, public safety officers, and agricultural extension agents. Partnership in identifying problems and setting goals is especially important because it brings commitment from all persons involved, which is essential to successful change (Biel et al, 2009).

A growing body of literature supports the significance and effectiveness of partnership in improving community health. Studies document the use of partnership models for a wide range of outcomes such as diabetes prevention, environmental justice, exercise, in data analysis, and as a proposed model for international development (Cashman et al, 2008; Merriam et al, 2009; Powell et al, 2010; Yoo et al, 2009). The roles of these partners-in-health have included listening sympathetically, offering advice, making referrals, and starting programs among a wide range of communities. These include urban Hispanics and rural Hispanic migrant farm workers (Connor et al, 2007; Mendelson et al, 2008). They include partnerships with older adults in retirement communities as well as smaller, more rural communities (Christopher et al, 2008; Davies et al, 2008) (Figure 18-1). There are also examples of community partnerships for at-risk students at the grade school or middle school level; for promoting policies to strengthen early childhood development; or for disaster planning (Adams and Canclini, 2008; Horsley and Ciske, 2005; Powell et al, 2010; Sangster, Eccleston, and Porter, 2008; Schwartz and Laughlin, 2008). Powell et al (2010) propose the continuing use of partnership models for “transforming and sustaining international development.” In international health, partnership models are generally viewed as empowering people, through their lay leaders, to control their own health destinies and lives. In the United States, partnership models have often involved informal community leaders, organizations such as churches, and communities.

Partnerships involving nurses working with community organizations offer one of the most effective means for interventions because they actively involve the community and build on existing community strengths. Nurses working with community groups and organizations fulfill many different roles. These roles include media advocacy, political action, “grass roots health communication and social marketing,” and outreach facilitation to get more community members involved, for example, in a school health fair. Regardless of what roles nurses fulfill as their contribution to the partnership, they must remember to “start where the people are” (Severance and Zinnah, 2009).

Shoultz et al (2006) looked at the challenges and possible solutions in developing partnerships with communities. Community partnerships involve both influence and power. Nurses must focus on where and how health professionals and the lay community can work together on an equal power basis. This requires equally respected inputs and voices that are equally heard. This approach requires nurses to do “with” rather than “to” the partner, while the partner’s role throughout the process is active and empowered, not passive. Goal setting and the plan of action are mutually determined. Roles and responsibilities are negotiated and the partners become more effective at working independently to solve their own problems and make decisions for themselves, even if they do not solve the problems identified by the nursing diagnosis. In the language of community empowerment advocates, community participants must have an active role in the change process. The public health nurses must work hard to include members of a setting, neighborhood, or organization while developing trust and providing the community with a say and a central role throughout the process (Christopher et al, 2008; Hanks, 2006).