After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Describe therapeutic use of self. • Identify and describe the phases of the traditional nurse-patient relationship. • Differentiate between social and professional relationships. • Explore the role self-awareness plays in the ability to use nonjudgmental acceptance as a helping technique. • Explain the concept of professional boundaries. • Discuss factors creating successful or unsuccessful communication. • Evaluate helpful and unhelpful communication techniques. • Identify strategies in providing care to patients who do not speak English. • Understand the roles of professional interpreters and translators. • Identify his or her own communication strengths and challenges. • Demonstrate components of active listening. • Identify key aspects of collaboration. • Explain the effect of gender, cultural, and generational diversity on nurse-patient and nurse-colleague relationships. To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional. The previous contributions of Kay K. Chitty to this chapter are acknowledged with gratitude. Chapter opening photo from istockphoto.com. Hildegard Peplau, a pioneer in nursing theory development, first focused on the importance of the nurse-patient relationship in her 1952 book Interpersonal Relations in Nursing. She referred to the use of one’s personality and communication skills to help patients as the “therapeutic use of self” (Peplau, 1952), a strategy that you can develop with practice. Therapeutic use of self can be helpful to you in relating effectively to patients, patients’ families, and other health care professionals. Because termination is often painful, participants are often tempted to continue the relationship on a social basis, and requests for screen names for social media, addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses are not uncommon. The nurse must realize that professional relationships are different from social relationships. This is an issue of professional boundaries that has been discussed earlier in this text. Differences between social and professional relationships are outlined in Box 9-1. Baca (2011) listed five ways in which self-disclosure becomes problematic: (1) if the nurse’s problems or needs are disclosed; (2) if disclosure by the nurse becomes a common, rather than rare, event during interactions with a patient; (3) when the disclosure is unrelated to the patient’s problems or experiences; (4) if it takes more than a very short time during an interaction; and (5) the nurse discloses personal information even if it is clear that the patient is confused by the interaction. Becoming aware of one’s needs and making conscious efforts to have those needs met in one’s private life keep relationships with patients professional and therapeutic for the patient. When the nurse-patient relationship crosses professional boundaries, role confusion can result, risking harm to both patient and nurse. Boundary issues are everywhere in nursing. They were first addressed by Florence Nightingale in the Nightingale Pledge (refer to Box 3-1 on p. 58 to review this statement). The American Nurses Association’s (ANA”s) Code of Ethics for Nurses (2001) also addressed boundaries. The subject of professional boundaries was detailed comprehensively by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). The NCSBN defined professional boundaries as “the spaces between the nurse’s power and the client’s vulnerability. The power of the nurse comes from the professional position and the access to private knowledge about the client” (NCSBN, 1996, p. 1). Boundary violations occur when “there is confusion between the needs of the nurse and those of the client” (p. 2). According to the NCSBN, nurse-patient relationships can be plotted on a continuum of professional behavior that ranges from underinvolvement (such as distancing, disinterest, neglect) through a zone of helpfulness (the ideal space) to overinvolvement (such as excessive personal disclosure by the nurse, secrecy, role reversal, touching, gestures, money or gifts, special attention, social contact, getting involved in a patient’s personal affairs, and/or sexual misconduct). Both underinvolvement and overinvolvement can be detrimental to patient and nurse (p. 3). A quick way of monitoring yourself with regard to boundaries is to ask yourself, “Can I tell a colleague about this?” If the answer is no, then you are at least on the edge of a boundary violation and need to take corrective measures. Secretive behavior is a signal that a nurse does not feel comfortable or is unwilling to share with trusted others (Baca, 2011). Box 9-2 describes a case in which a nurse was disciplined by his state board of nursing for failing to honor the professional boundaries between a nurse and patient. Failure to maintain professional boundaries with a patient is an offense reportable to your employer and/or your state board of nursing and violates nursing’s code of ethics. This means that nurses should have a thorough understanding of professional boundaries. Box 9-3 contains seven principles to guide nurses in determining professional boundaries across the continuum of professional behavior (NCBSN, 1996). You can find a .PDF file of the popular NCBSN publication explaining professional boundaries by following the links at www.ncsbn.org. Developing self-awareness requires individuals to engage in personal reflection. This requires taking time to focus on their own thoughts, feelings, actions, and beliefs. Finding the time and space for reflective practice can be a challenge to busy students and practicing nurses alike. Reflection can produce discomfort as nurses become aware of the tensions and anxieties within themselves about their everyday activities. Nurses and nursing students may find that their personal values are challenged by the realities of practice. Importantly, nurses may recognize in themselves a desensitization to the needs of their patients because of time constraints, the need to create emotional space, or a personal dislike for a particular patient. It can be hard for you when you recognize that you may have thoughts that are less than kind about patients entrusted to your care. This makes the need for reflection more, not less, important. No human being is immune from emotional responses to others, both positive and negative. Despite the difficulty in coming to terms with your emotional responses to patients and to your work, becoming self-aware allows you to understand your responses and to look past your own negative (and positive) responses to particular patients in order to create and maintain a healthy professional space in which you can provide care most effectively. Box 9-4 contains a model for structured reflection that will be helpful to you reflecting on your practice and becoming more self-aware. The traditional nurse-patient relationship has been taught and practiced since the middle of the twentieth century; however, several assumptions on which it is based no longer hold true in many of today’s practice settings. For instance, this older model assumes that the development of the nurse-patient relationship is linear, is incremental, and requires trust-building in the earliest phases of the relationship, and importantly, it assumes that patients desire relationships with nurses, wish to receive services from them, and will cooperate and comply with those nurses (Hagerty and Patusky, 2003). Patient-centered care has been proposed as an approach to alleviating some of the difficult problems that currently trouble the U.S. health care system, such as poor care quality, limited access to care, and dehumanization of care (Hobbs, 2009). In a detailed analysis, Hobbs found that alleviating vulnerabilities (e.g., feeling alienated, lack of control) experienced by the patient is central to patient-centered care in acute care settings. Furthermore, the process of therapeutic engagement is the key process in alleviating vulnerabilities, and one of the mechanisms by which this occurs is by the nurse’s caring presence (p. 55). Theories of caring and human relatedness provide a powerful basis for practice. Many theorists have written about the nature of the nurse-patient relationship, with several writing about caring as the central concept in nursing, through which effective nursing practice occurs. Swanson (1991) defined caring as “a nurturing way of relating to a valued other, toward whom one feels a personal sense of commitment and responsibility” (p. 165). Five caring processes are germane to nursing practice: (1) knowing, (2) being with, (3) doing for, (4) enabling, and (5) maintaining belief (Swanson, 1991). Others have written about caring in nursing, including Watson (1988), whose theory is discussed in Chapter 13, and Roach and Maykut (2010), who described the essential elements of comportment central to professional caring. Hagerty and Patusky (2003) proposed a theory of human relatedness through which to conceptualize the nurse-patient relationship. Each nurse-patient contact holds the potential for connection and goal achievement, as opposed to one step in a lengthy relationship-building process. They also recommended that nurses approach their patients with a sense of the patient’s autonomy, choice, and participation (p. 147), putting the relationship on a more equitable basis than the traditional nurse-patient relationship, which gives much of the power to the nurse. Communication is the exchange of thoughts, ideas, or information and is at the heart of all relationships. Jurgen Ruesch (1972), a pioneer communications theorist, defined communication as “all the modes of behavior that one individual employs, conscious or unconscious, to affect another: not only the spoken and written word, but also gestures, body movements, somatic signals, and symbolism in the arts” (p. 16). Communication exists simultaneously on at least two levels: verbal and nonverbal. Verbal communication consists of all speech and represents the most obvious aspect of communication. Much of one’s message, however, consists of nonverbal communication. Nonverbal communication includes grooming, clothing, gestures, posture, facial expressions, eye contact, tone and volume of voice, and actions, among other things (Figure 9-1). Words can be used to mask feelings, but individuals are less able to exercise conscious control over nonverbal communication than verbal communication, therefore the nonverbal component may be a more reliable expression of feeling. Nurses must pay attention to nonverbal messages as closely as they do to verbal ones. Five major elements must be present for communication to occur: a sender, a message, a receiver, feedback, and a context (Ruesch, 1972). The sender is the person sending the message; the message is what is actually said plus accompanying nonverbal communication; the receiver is the person acquiring the message. A response to a message is termed feedback. The setting in which an interaction occurs—including the mood, relationship between sender and receiver, and other factors—is known as the context. All of these elements are necessary for communication to occur. Consider the classroom situation. During a lecture, the professor is the sender, the lecture is the message, and students are the receivers. The professor (sender) receives feedback from the students (receivers) through their facial expressions, alertness, posture, attentiveness, and comments. The atmosphere in the classroom is the context. If the atmosphere is a relaxed one of give-and-take discussion between students and professor, the feedback is quite different from feedback in a more formal context of professor as lecturer and students as note takers. Figure 9-2 shows the relationships among the elements of communication.

Communication and collaboration in nursing

Therapeutic use of self

The traditional nurse-patient relationship

The termination phase

Developing self-awareness

Professional boundaries

Reflective practice

Thinking differently about nurses and patients: Caring and human relatedness

Patient-centered care

Communication theory

Levels of communication

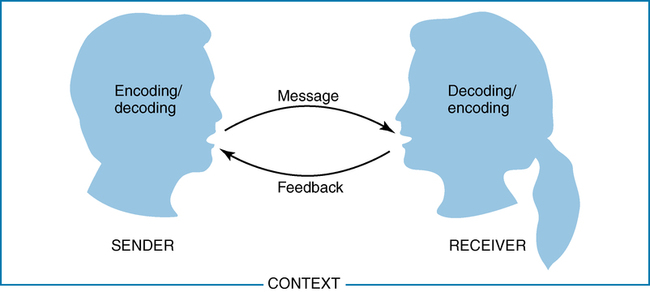

Elements of the communication process

Communication and collaboration in nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access