Communication

Objectives

• Describe aspects of critical thinking that are important to the communication process.

• Describe the five levels of communication and their uses in nursing.

• Describe the basic elements of the communication process.

• Identify significant features and therapeutic outcomes of nurse-patient helping relationships.

• Identify significant features and desired outcomes of nurse–health care team member relationships.

• Describe qualities, behaviors, and communication techniques that affect professional communication.

• Discuss effective communication techniques for older patients.

• Identify patient health states that contribute to impaired communication.

• Discuss nursing care measures for patients with special communication needs.

Key Terms

Active listening, p. 320

Assertiveness, p. 317

Autonomy, p. 317

Channels, p. 312

Communication, p. 309

Empathy, p. 320

Environment, p. 312

Feedback, p. 312

Interpersonal communication, p. 311

Interpersonal variables, p. 312

Intrapersonal communication, p. 311

Message, p. 312

Metacommunication, p. 314

Nonverbal communication, p. 313

Perceptual biases, p. 310

Public communication, p. 311

Receiver, p. 312

Referent, p. 312

Sender, p. 312

Small-group communication, p. 311

Symbolic communication, p. 314

Sympathy, p. 323

Therapeutic communication, p. 320

Transpersonal communication, p. 311

Verbal communication, p. 313

![]()

Communication and Nursing Practice

Communication is a lifelong learning process. Nurses make the intimate journey with patients and their families from the miracle of birth to the mystery of death. As a nurse you communicate with patients and families to collect meaningful assessment data, provide education, and interact using therapeutic communication to promote personal growth and attainment of health-related goals. Despite the complexity of technology and the multiple demands on nurses’ time, it is the intimate moment of connection that makes all the difference in the quality of care and meaning for a patient and a nurse.

Communication is an essential part of patient-centered nursing care. Patient safety also requires effective communication among members of the health care team as patients move from one caregiver to another or from one care setting to another. Breakdown in communication among the health care team is a major cause of errors in the workplace and threatens professional credibility (World Health Organization, 2007). Effective team communication and collaboration skills are essential to ensure patient safety and high-quality patient care (Cronenwett et al., 2007). Competency in communication helps maintain effective relationships within the entire sphere of professional practice and meets legal, ethical, and clinical standards of care.

The qualities, behaviors, and therapeutic communication techniques described in this chapter characterize professionalism in helping relationships. Although the term patient is often used, the same principles apply when communicating with any person in any nursing situation.

Communication and Interpersonal Relationships

Caring relationships formed among a nurse and those affected by a nurse’s practice are at the core of nursing (see Chapter 7). Communication is the means of establishing these helping-healing relationships. All behavior communicates, and all communication influences behavior. For these reasons communication is essential to the nurse-patient relationship.

Nurses with expertise in communication express caring by the following (Watson, 1985):

• Becoming sensitive to self and others

• Promoting and accepting the expression of positive and negative feelings

• Developing helping-trust relationships

• Promoting interpersonal teaching and learning

• Providing a supportive environment

• Assisting with gratification of human needs

A nurse’s ability to relate to others is important for interpersonal communication. This includes the ability to take initiative in establishing and maintaining communication, to be authentic (one’s self), and to respond appropriately to the other person. Effective interpersonal communication also requires a sense of mutuality, a belief that the nurse-patient relationship is a partnership and that both are equal participants. Nurses honor the fact that people are very complex and ambiguous. Often more is communicated than first meets the eye, and patient responses are not always what you expect. By giving all of your attention to a patient, you attend to the patient’s needs and aid the healing process (Tavernier, 2006). Most nurses embrace the profession’s view of the holistic nature of people and experience synergy in human interaction. When patients and nurses work together, much can be accomplished.

Therapeutic communication occurs within a healing relationship between a nurse and patient (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). Like any powerful therapeutic agent, the nurse’s communication can result in both harm and good. Every nuance of posture, every small expression and gesture, every word chosen, every attitude held—all have the potential to hurt or heal, affecting others through the transmission of human energy. Knowing that intention and behavior directly influence health gives nurses tremendous ethical responsibility to do no harm to those entrusted to their care. Respect the potential power of communication and do not carelessly misuse communication to hurt, manipulate, or coerce others. Skilled communication empowers others and enables people to know themselves and make their own choices, an essential aspect of the healing process. Nurses have wonderful opportunities to bring about good things for themselves, their patients, and their colleagues through this kind of therapeutic communication.

Developing Communication Skills

Gaining expertise in communication requires both an understanding of the communication process and reflection about one’s communication experiences as a nurse. Nurses who develop critical thinking skills make the best communicators. They draw on theoretical knowledge about communication and integrate this knowledge with knowledge previously learned through personal experience. They interpret messages received from others, analyze their content, make inferences about their meaning, evaluate their effect, explain rationale for communication techniques used, and self-examine personal communication skills (Balzer-Riley, 2007).

Critical thinking in nursing, based on established standards of nursing care and ethical standards, promotes effective communication. When you consider a patient’s problems, it is important to apply critical thinking standards to ensure sound effective communication (Chitty, 2010). For example, curiosity motivates a nurse to communicate and know more about a person. Patients are more likely to communicate with nurses who express an interest in them. Perseverance and creativity are also attitudes conducive to communication because they motivate a nurse to communicate and identify innovative solutions. A self-confident attitude is important because a nurse who conveys confidence and comfort while communicating more readily establishes an interpersonal helping-trusting relationship. In addition, an independent attitude encourages a nurse to communicate with colleagues and share ideas about nursing interventions. Such an attitude often involves risk taking because colleagues sometimes question suggested nursing interventions. At the same time, an attitude of fairness goes a long way in the ability to listen to both sides in any discussion. Integrity allows nurses to recognize when their opinions conflict with those of their patients, review positions, and decide how to communicate to reach mutually beneficial decisions. It is also very important for a nurse to communicate responsibly and ask for help if uncertain or uncomfortable about an aspect of patient care. An attitude of humility is necessary to recognize and communicate the need for more information before making a decision (Paul, 1993).

It is challenging to understand human communication within interpersonal relationships. Each individual bases his or her perceptions about information received through the five senses of sight, hearing, taste, touch, and smell (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). An individual’s culture and education also influence perception. Critical thinking helps nurses overcome perceptual biases, or human tendencies that interfere with accurately perceiving and interpreting messages from others. People often assume that others think, feel, act, react, and behave as they would in similar circumstances. They tend to distort or ignore information that goes against their expectations, preconceptions, or stereotypes (Beebe et al., 2010). By thinking critically about personal communication habits, you learn to control these tendencies and become more effective in interpersonal relationships.

As communication skills develop, competence in the nursing process also grows. You need to integrate communication skills throughout the nursing process as you collaborate with patients and health care team members to achieve goals (Box 24-1). Use communication skills to gather, analyze, and transmit information and accomplish the work of each step of the process. Assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation all depend on effective communication among nurse, patient, family, and others on the health care team. Although the nursing process is a reliable framework for patient care, it does not work well unless you master the art of effective interpersonal communication.

The nature of the communication process requires you to constantly make decisions about what, when, where, why, and how to convey a message. A nurse’s decision making is always contextual (i.e., the unique features of any situation influence the nature of the decisions made). For example, the explanation of the importance of following a prescribed diet to a patient with a newly diagnosed medical condition differs from the explanation to a patient who has repeatedly chosen not to follow diet restrictions. Effective communication techniques are easy to learn, but their application is more difficult. Deciding which techniques best fit each unique nursing situation is challenging. Communication about specific diagnoses such as cancer or end of life and dealing with patient and family emotions can be challenging, and some nurses struggle to cope with their own reactions and emotions (Sheldon et al., 2006).

Throughout this chapter brief clinical examples guide you in the use of effective communication techniques. Situations that challenge a nurse’s decision-making skills and call for careful use of therapeutic techniques often involve the types of persons described in Box 24-2. Because the best way to acquire skill is through practice, it is useful for you to discuss and role-play these scenarios before experiencing them in the clinical setting. Consider who is involved in the situation to decide which communication will be most effective.

Levels of Communication

Nurses use different levels of communication in their professional role. A competent nurse uses a variety of techniques in each level.

Intrapersonal communication is a powerful form of communication that occurs within an individual. This level of communication is also called self-talk, self-verbalization, or inner thought. People’s thoughts strongly influence perceptions, feelings, behavior, and self-concept. You need to be aware of the nature and content of your own thinking. Self-talk provides a mental rehearsal for difficult tasks or situations so individuals deal with them more effectively and with increased confidence (Gibson and Foster, 2007; White, 2008). Nurses and patients use intrapersonal communication to develop self-awareness and a positive self-concept that enhances appropriate self-expression. For example, you improve your health and self-esteem through positive self-talk by replacing negative thoughts with positive assertions.

Interpersonal communication is one-on-one interaction between a nurse and another person that often occurs face to face. It is the level most frequently used in nursing situations and lies at the heart of nursing practice. It takes place within a social context and includes all the symbols and cues used to give and receive meaning. Because meaning resides in persons and not in words, messages received are sometimes different from intended messages. Nurses work with people who have different opinions, experiences, values, and belief systems; thus it is important to validate meaning or mutually negotiate it between participants. For example, use interaction to assess understanding and clarify misinterpretations when teaching a patient about a health concern. Meaningful interpersonal communication results in exchange of ideas, problem solving, expression of feelings, decision making, goal accomplishment, team building, and personal growth.

Transpersonal communication is interaction that occurs within a person’s spiritual domain. Study of the influence of religion and spirituality has increased dramatically in recent years, and ongoing research helps us understand the role of nurses in addressing a patient’s spiritual needs (Pesut et al., 2008). Many people use prayer, meditation, guided reflection, religious rituals, or other means to communicate with their “higher power.” Nurses have a responsibility to assess a patient’s spiritual needs and intervene to meet those needs (see Chapter 35).

Small-group communication is interaction that occurs when a small number of persons meet. This type of communication is usually goal directed and requires an understanding of group dynamics. When nurses work on committees, lead patient support groups, form research teams, or participate in patient care conferences, they use a small-group communication process. Small groups are most effective when they are cohesive and committed and have an appropriate meeting place with suitable seating arrangements (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). A nurse’s role varies with the function of a group. He or she frequently coordinates the group, provides recognition and acceptance of the contributions of each group member, and provides encouragement and motivation to help the group meet its goals (Townsend, 2009).

Public communication is interaction with an audience. Nurses have opportunities to speak with groups of consumers about health-related topics, present scholarly work to colleagues at conferences, or lead classroom discussions with peers or students. Public communication requires special adaptations in eye contact, gestures, voice inflection, and use of media materials to communicate messages effectively. Effective public communication increases audience knowledge about health-related topics, health issues, and other issues important to the nursing profession.

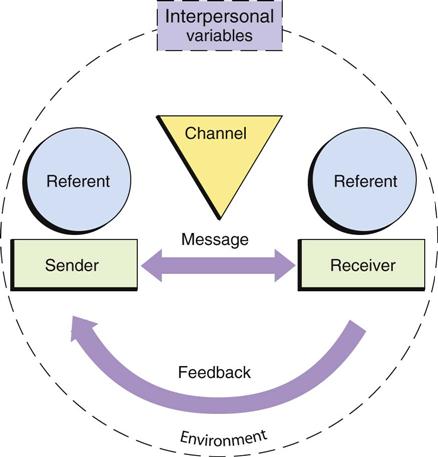

Basic Elements of the Communication Process

Communication is an ongoing, dynamic, and multidimensional process. Fig. 24-1 shows the basic elements of the communication process. This simple linear model represents a very complex process with its essential components. Nursing situations have many unique aspects that influence the nature of communication and interpersonal relationships. As a professional, you will use critical thinking to focus on each aspect of communication so your interactions are purposeful and effective.

Referent

The referent motivates one person to communicate with another. In a health care setting sights, sounds, odors, time schedules, messages, objects, emotions, sensations, perceptions, ideas, and other cues initiate communication. Knowing which stimulus initiates communication enables you to develop and organize messages more efficiently and better perceive meaning in another’s message. A patient request for help prompted by difficulty breathing brings a different nursing response than a request prompted by hunger.

Sender and Receiver

The sender is the person who encodes and delivers the message, and the receiver is the person who receives and decodes the message. The sender puts ideas or feelings into a form that is transmitted and is responsible for the accuracy of its content and emotional tone. The sender’s message acts as a referent for the receiver, who is responsible for attending to, translating, and responding to the sender’s message. Sender and receiver roles are fluid and change back and forth as two persons interact; sometimes sending and receiving occurs simultaneously. The more the sender and receiver have in common and the closer the relationship, the more likely they will accurately perceive one another’s meaning and respond accordingly.

Messages

The message is the content of the communication. It contains verbal, nonverbal, and symbolic language. Personal perceptions sometimes distort the receiver’s interpretation of the message. Two nurses can provide the same information yet convey very different messages because of their personal communication styles. Two persons understand the same message differently. You send effective messages by expressing clearly, directly, and in a manner familiar to the receiver. You determine the need for clarification by watching the listener for nonverbal cues that suggest confusion or misunderstanding. Communication is difficult when participants have different levels of education and experience. “Your incision is well approximated without purulent drainage” means the same as “Your wound edges are close together, and there are no signs of infection,” but the latter is easier to understand. You can also send messages in writing, but make sure that patients are able to read.

Channels

Channels are means of conveying and receiving messages through visual, auditory, and tactile senses. Facial expressions send visual messages, spoken words travel through auditory channels, and touch uses tactile channels. Individuals usually understand a message more clearly when the sender uses more channels to convey it. For example, when teaching about insulin self-injection, the nurse talks about and demonstrates the technique, gives the patient printed information, and encourages hands-on practice with the vial and syringe. Nurses use verbal, nonverbal, and mediated (technological) communication channels. They send and receive information in person, by informal or formal writing, over the telephone or pager, by audiotape and videotape, through fax and electronic mail, and through interactive and informational websites.

Feedback

Feedback is the message the receiver returns. It indicates whether the receiver understood the meaning of the sender’s message. Senders seek verbal and nonverbal feedback to evaluate the effectiveness of communication. The sender and receiver need to be sensitive and open to one another’s messages, clarify the messages, and modify behavior accordingly. In a social relationship both persons assume equal responsibility for seeking openness and clarification, but the nurse assumes primary responsibility in the nurse-patient relationship.

Interpersonal Variables

Interpersonal variables are factors within both the sender and receiver that influence communication. Perception is one such variable that provides a uniquely personal view of reality formed by an individual’s expectations and experiences. Each person senses, interprets, and understands events differently. A nurse says, “You have been very quiet since your family left. Is there something on your mind?” One patient may perceive the nurse’s question as caring and concerned; another perceives the nurse as invading privacy and is less willing to talk. Other interpersonal variables include educational and developmental levels, sociocultural backgrounds, values and beliefs, emotions, gender, physical health status, and roles and relationships. Variables associated with illness such as pain, anxiety, and medication effects also affect nurse-patient communication.

Environment

The environment is the setting for sender-receiver interaction. For effective communication the environment needs to meet participant needs for physical and emotional comfort and safety. Noise, temperature extremes, distractions, and lack of privacy or space create confusion, tension, and discomfort. Environmental distractions are common in health care settings and interfere with messages sent between people. You control the environment as much as possible to create favorable conditions for effective communication.

Forms of Communication

Messages are conveyed verbally and nonverbally, concretely and symbolically. As people communicate, they express themselves through words, movements, voice inflection, facial expressions, and use of space. These elements work in harmony to enhance a message or conflict with one another to contradict and confuse it.

Verbal Communication

Verbal communication uses spoken or written words. Verbal language is a code that conveys specific meaning through a combination of words. The most important aspects of verbal communication are presented in the following paragraphs.

Vocabulary

Communication is unsuccessful if senders and receivers cannot translate one another’s words and phrases. When a nurse cares for a patient who speaks another language, an interpreter is often necessary. Even those who speak the same language use subcultural variations of certain words (e.g., dinner means a noon meal to one person and the last meal of the day to another). Medical jargon (technical terminology used by health care providers) sounds like a foreign language to patients unfamiliar with the health care setting. Limiting use of medical jargon to conversations with other health care team members improves communication. Children have a more limited vocabulary than adults. They may use special words to describe bodily functions or a favorite blanket or toy. Teenagers often use words in unique ways that are unfamiliar to adults.

Denotative and Connotative Meaning

Some words have several meanings. Individuals who use a common language share the denotative meaning: baseball has the same meaning for everyone who speaks English, but code denotes cardiac arrest primarily to health care providers. The connotative meaning is the shade or interpretation of the meaning of a word influenced by the thoughts, feelings, or ideas people have about the word. For example, health care providers tell a family that a loved one is in serious condition, and they believe that death is near; but to nurses serious simply describes the nature of the illness. You need to carefully select words, avoiding easily misinterpreted words, especially when explaining a patient’s medical condition or therapy. Even a much-used phrase such as “I’m going to take your vital signs” may be unfamiliar to an adult or frightening to a child.

Pacing

Conversation is more successful at an appropriate speed or pace. Speak slowly and enunciate clearly. Talking rapidly, using awkward pauses, or speaking slowly and deliberately conveys an unintended message. Long pauses and rapid shifts to another subject give the impression that you are hiding the truth. Think before speaking and develop an awareness of the rhythm of your speech to improve pacing.

Intonation

Tone of voice dramatically affects the meaning of a message. Depending on intonation, even a simple question or statement expresses enthusiasm, anger, concern, or indifference. Be aware of voice tone to avoid sending unintended messages. For example, a patient interprets a nurse’s patronizing tone of voice as condescending, and this inhibits further communication. A patient’s tone of voice often provides information about his or her emotional state or energy level.

Clarity and Brevity

Effective communication is simple, brief, and direct. Fewer words result in less confusion. Speaking slowly, enunciating clearly, and using examples to make explanations easier to understand improve clarity. Repeating important parts of a message also clarifies communication. Phrases such as “you know” or “OK?” at the end of every sentence detract from clarity. Use short sentences and words that express an idea simply and directly. “Where is your pain?” is much better than “I would like you to describe for me the location of your discomfort.”

Timing and Relevance

Timing is critical in communication. Even though a message is clear, poor timing prevents it from being effective. For example, you do not begin routine teaching when a patient is in severe pain or emotional distress. Often the best time for interaction is when a patient expresses an interest in communicating. If messages are relevant or important to the situation at hand, they are more effective. When a patient is facing emergency surgery, discussing the risks of smoking is less relevant than explaining presurgical procedures.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication includes the five senses and everything that does not involve the spoken or written word. Researchers have estimated that approximately 7% of meaning is transmitted by words, 38% is transmitted by vocal cues, and 55% is transmitted by body cues. Thus nonverbal communication is unconsciously motivated and more accurately indicates a person’s intended meaning than the spoken words (Jones, 2009). When there is incongruity between verbal and nonverbal communication, the receiver usually “hears” the nonverbal message as the true message.

All kinds of nonverbal communication are important, but interpreting them is often problematic. Sociocultural background is a major influence on the meaning of nonverbal behavior. In the United States, with its diverse cultural communities, nonverbal messages between people of different cultures are easily misinterpreted. Because the meaning attached to nonverbal behavior is so subjective, it is imperative that you verify it (Stuart, 2009). Assessing nonverbal messages is an important nursing skill.

Personal Appearance

Personal appearance includes physical characteristics, facial expression, and manner of dress and grooming. These factors help communicate physical well-being, personality, social status, occupation, religion, culture, and self-concept. First impressions are largely based on appearance. Nurses learn to develop a general impression of patient health and emotional status through appearance, and patients develop a general impression of the nurse’s professionalism and caring in the same way.

Posture and Gait

Posture and gait (way of walking) are forms of self-expression. The way people sit, stand, and move reflects attitudes, emotions, self-concept, and health status. For example, an erect posture and a quick, purposeful gait communicate a sense of well-being and confidence. Leaning forward conveys attention. A slumped posture and slow shuffling gait indicates depression, illness, or fatigue.

Facial Expression

The face is the most expressive part of the body. Facial expressions convey emotions such as surprise, fear, anger, happiness, and sadness. Some people have an expressionless face, or flat affect, which reveals little about what they are thinking or feeling. An inappropriate affect is a facial expression that does not match the content of a verbal message (e.g., smiling when describing a sad situation). People are sometimes unaware of the messages their expressions convey. For example, a nurse frowns in concentration while doing a procedure, and the patient interprets this as anger or disapproval. Patients closely observe nurses. Consider the impact a nurse’s facial expression has on a person who asks, “Am I going to die?” The slightest change in the eyes, lips, or facial muscles reveals the nurse’s feelings. Although it is hard to control all facial expressions, try to avoid showing shock, disgust, dismay, or other distressing reactions in a patient’s presence.

Eye Contact

People signal readiness to communicate through eye contact. Maintaining eye contact during conversation shows respect and willingness to listen. Eye contact also allows people to closely observe one another. Lack of eye contact may indicate anxiety, defensiveness, discomfort, or lack of confidence in communicating. However, persons from some cultures consider eye contact intrusive, threatening, or harmful and minimize or avoid its use (see Chapter 9). Always consider a person’s culture when interpreting the meaning of eye contact. Eye movements communicate feelings and emotions. Looking down on a person establishes authority, whereas interacting at the same eye level indicates equality in the relationship. Rising to the same eye level as an angry person helps establish autonomy.

Gestures

Gestures emphasize, punctuate, and clarify the spoken word. Gestures alone carry specific meanings, or they create messages with other communication cues. A finger pointed toward a person communicates several meanings; but, when accompanied by a frown and stern voice, the gesture becomes an accusation or threat. Pointing to an area of pain is sometimes more accurate than describing its location.

Sounds

Sounds such as sighs, moans, groans, or sobs also communicate feelings and thoughts. Combined with other nonverbal communication, sounds help to send clear messages. They have several interpretations: moaning conveys pleasure or suffering, and crying communicates happiness, sadness, or anger. Validate nonverbal messages with the patient to interpret them accurately.

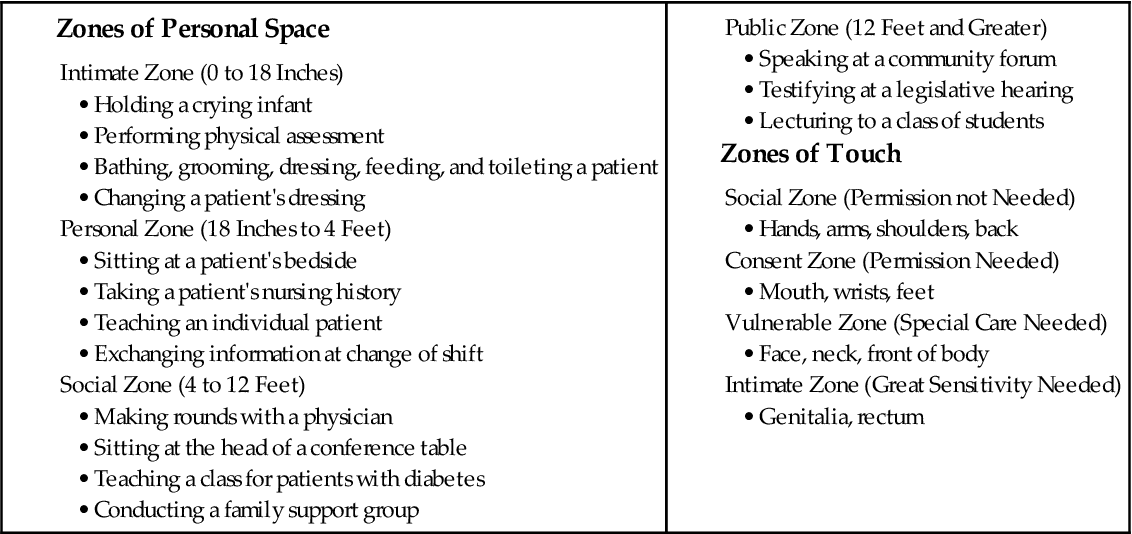

Territoriality and Personal Space

Territoriality is the need to gain, maintain, and defend one’s right to space. Territory is important because it provides people with a sense of identity, security, and control. It is sometimes separated and made visible to others such as a fence around a yard or a bed in a hospital room. Personal space is invisible, individual, and travels with the person. During interpersonal interaction, people maintain varying distances between each other, depending on their culture, the nature of their relationship, and the situation. When personal space becomes threatened, people respond defensively and communicate less effectively. Situations dictate whether the interpersonal distance between nurse and patient is appropriate. Box 24-3 provides examples of nursing actions within zones of personal space and touch (Kneisl and Trigoboff, 2009; Stuart, 2009). Nurses frequently move into patients’ territory and personal space because of the nature of caregiving. You need to convey confidence, gentleness, and respect for privacy, especially when your actions require intimate contact or involve a patient’s vulnerable zone.

Symbolic Communication

Good communication requires awareness of symbolic communication, the verbal and nonverbal symbolism used by others to convey meaning. Art and music are forms of symbolic communication used by nurses to enhance understanding and promote healing. Lane (2006) found that creative expressions such as art, music, and dance have a healing effect on patients. Patients reported decreased pain and a greater sense of joy and hope.

Metacommunication

Metacommunication is a broad term that refers to all factors that influence communication. Awareness of influencing factors helps people better understand what is communicated (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). For example, a nurse observes a young patient holding his body rigidly, and his voice is sharp as he says, “Going to surgery is no big deal.” The nurse replies, “You say having surgery doesn’t bother you, but you look and sound tense. I’d like to help.” Awareness of the tone of the verbal response and the nonverbal behavior results in further exploration of the patient’s feelings and concerns.

Professional Nursing Relationships

A nurse’s application of knowledge, understanding of human behavior and communication, and commitment to ethical behavior help create professional relationships. Having a philosophy based on caring and respect for others helps you be more successful in establishing relationships of this nature.

Nurse-Patient Helping Relationships

Helping relationships are the foundation of clinical nursing practice. In such relationships you assume the role of professional helper and come to know a patient as an individual who has unique health needs, human responses, and patterns of living. Therapeutic relationships promote a psychological climate that facilitates positive change and growth. Therapeutic communication between you and your patients allows the attainment of health-related goals (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). The goals of a therapeutic relationship focus on a patient achieving optimal personal growth related to personal identity, ability to form relationships, and ability to satisfy needs and achieve personal goals (Stuart, 2009). There is an explicit time frame, a goal-directed approach, and a high expectation of confidentiality. A nurse establishes, directs, and takes responsibility for the interaction; and a patient’s needs take priority over a nurse’s needs. Your nonjudgmental acceptance of a patient is an important characteristic of the relationship. Acceptance conveys a willingness to hear a message or acknowledge feelings. It does not mean that you always agree with the other person or approve of the patient’s decisions or actions. A helping relationship between you and a patient does not just happen—you create it with care, skill, and trust.

A natural progression of four goal-directed phases characterizes the nurse-patient relationship. The relationship often begins before you meet a patient and continues until the caregiving relationship ends (Box 24-4). Even a brief interaction uses an abbreviated version of the same preinteraction, orientation, working, and termination phases (Stuart, 2009). For example, the nursing student gathers patient information to prepare in advance for caregiving, meets the patient and establishes trust, accomplishes health-related goals through use of the nursing process, and says goodbye at the end of the day.

Socializing is an important initial component of interpersonal communication. It helps people get to know one another and relax. It is easy, superficial, and not deeply personal; whereas therapeutic interactions are often more intense, difficult, and uncomfortable. A nurse often uses social conversation to lay a foundation for a closer relationship: “Hi, Mr. Simpson, I hear it’s your birthday today. How old are you?” A friendly, informal, and warm communication style helps establish trust, but you have to get beyond social conversation to talk about issues or concerns affecting the patient’s health. During social conversation some patients ask personal questions such as those about your family or place of residence. Students often wonder whether it is appropriate to reveal such information. The skillful nurse uses judgment about what to share and provides minimal information or deflects such questions with gentle humor and refocuses conversation back to the patient.

Creating a therapeutic environment depends on your ability to communicate, comfort, and help patients meet their needs. Comfort is a critical value inherent in the practice of nursing. Therapeutic interactions increase feelings of personal control by helping a person feel secure, informed, and valued. Optimizing personal control facilitates emotional comfort, which minimizes physical discomfort and enhances recovery activities (Williams and Irurita, 2006).

In a therapeutic relationship it is important to encourage patients to share personal stories. Sharing stories is called narrative interaction. Through narrative interactions you begin to understand the context of others’ lives and learn what is meaningful for them from their perspective. For example, a nurse uses narratives to understand a patient’s perception of risk and the meaning of risk when taking medication that increases the risk of bleeding (Andreas et al., 2010) and to explore patient experiences of dignity in care (Dawood and Gallini, 2010). It is important to listen to patient stories to better understand their concerns, experiences, and challenges. This information is not usually revealed using a standard history form that elicits short answers.

Nurse-Family Relationships

Many nursing situations, especially those in community and home care settings, require you to form helping relationships with entire families. The same principles that guide one-on-one helping relationships also apply when the patient is a family unit, although communication within families requires additional understanding of the complexities of family dynamics, needs, and relationships (see Chapter 10).

Nurse–Health Care Team Relationships

Communication with other members of the health care team affects patient safety and the work environment. Breakdown in communication is a frequent cause of serious injuries in health care settings (World Health Organization, 2007). When patients move from one nursing unit to another or from one provider to another, also known as hand-offs, there is a risk for miscommunication. Accurate communication is essential to prevent errors (Cronenwett et al., 2007).

Use of common language when communicating critical information helps prevent misunderstandings. SBAR is a popular communication tool that helps standardize communication among health care providers. SBAR stands for Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (Pope et al., 2008). Research indicates that effective communication between health care providers and other members of the health care team ensures patient safety and promotes optimal patient outcomes (Amato-Vealey, Barba, and Vealey, 2008). Evidence identifies nursing actions that increase effectiveness of nurse-to-nurse interaction and interprofessional communication (Box 24-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree