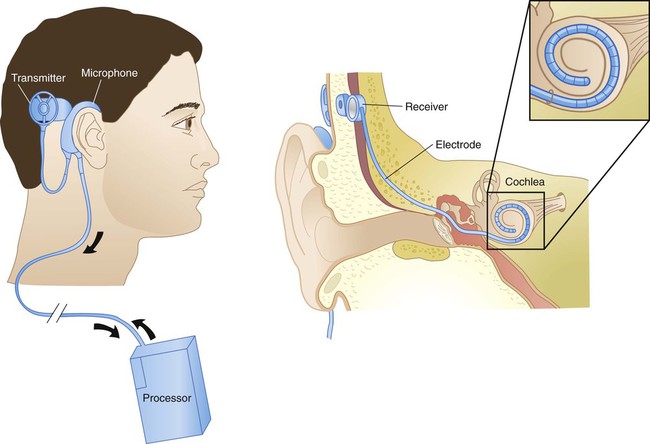

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Describe the importance of communication to the lives of older adults. 2. Discuss how ageist attitudes affect communication with older adults. 3. Discuss diseases of the eye and ear that may occur in older adults 4. Describe the importance of screening, health education, and treatment of eye diseases to prevent unnecessary vision loss 5. Identify effective communication strategies for older adults with speech, language, hearing, vision, and cognitive impairment. 6. Describe interventions that facilitate communication individually and in groups. 7. Understand the significance of the life story. 8. Discuss the modalities of reminiscence and life review. 9. Understand how health literacy affects communication and learning and design interventions to enhance understanding. Communication is the single most important capacity of human beings, the ability that gives us a special place in the animal kingdom. Little is more dehumanizing than the inability to communicate effectively and engage in social interaction with others. The need to communicate, to be listened to, and to be heard does not change with age or impairment. Meaningful communication and active engagement with society contributes to healthy aging and improves an older adult’s chances of living longer, responding better to health care interventions, and maintaining optimal function (Rowe and Kahn, 1998; Williams, 2006; Williams et al., 2008; Herman and Williams, 2009; Levy, 2009; Levy et al., 2009a,b; VanLeuven, 2010). Beliefs in myths and stereotypes about older adults and ageist attitudes can interfere with the ability to communicate effectively. For example, if the nurse believes that all older people have memory problems, or are unable to learn or process information, he or she will be less likely to engage in conversation, provide appropriate health information, or treat the person with respect and dignity. Ageism, a term coined by Robert Butler (1969), the first director of the National Institute on Aging (Bethesda, MD), is the systematic stereotyping of, and discrimination against, people because they are old, just as racism and sexism accomplish this with skin color and gender. Ageism will affect us all if we live long enough. Although ageism is found cross-culturally, it is essentially prevalent in the United States where aging is viewed with depression, fear, and anxiety (International Longevity Center, 2006). Ageist attitudes, as well as myths and stereotypes about aging, can be detrimental to older people. On the other hand, holding a positive self-perception of aging can contribute to a longer life span. The survival advantage of a more positive self-perception of aging can add 7.5 years to the life span and contributes more to added years of life than low body mass index, no smoking history, and exercise (Levy et al., 2002). While older people, collectively, have often been seen in negative terms, a most striking change in attitudes toward aging has occurred in the past 25 years. Undoubtedly, this will continue to change as the baby boomers reach retirement age. The impact of media presentation is enormous, and it is gratifying to see robust images of aging; fewer older people are portrayed as victims or as those to be pitied, shunned, or ridiculed by virtue of achieving old age. Elderspeak is a form of ageism in which younger people alter their speech, based on the assumption that all older people have difficulty understanding and comprehending (Touhy and Williams, 2008). It is especially common in communication between health care professionals and older adults in hospitals and nursing homes, but occurs in non–healthcare settings as well (Williams et al., 2003, 2004,2008; Williams, 2006; Williams and Tappen, 2008; Herman and Williams, 2009). Elderspeak is similar to “baby talk,” which is often used to talk to very young children (Box 6-1). Nurses may not be aware that they are using elderspeak, but research has shown that use of this form of speech is patronizing and conveys messages of dependence, incompetence, and control (Williams, 2006; Williams et al., 2008). Some features of elderspeak (speaking more slowly, repeating, or paraphrasing) may be beneficial in communication with older people with dementia, and further research is needed. Other examples of communication that conveys ageist attitudes are ignoring the older person and talking to family and friends as if the person were not present, and limiting interaction to task-focused communication only (Touhy and Williams, 2008). Although both vision and hearing impairment significantly affect all aspects of life, Oliver Sacks (1989), in his book Seeing Voices, presents a view that blindness may in fact be less serious than loss of hearing. Hearing loss interferes with communication with others and the interactional input that is so necessary to stimulate and validate. One elderly man said that a great annoyance of hearing loss is in the subtle aspects of living with a partner, who most probably has a hearing loss as well. “You must often repeat what you say, and in lovemaking, whispering sweet words becomes a gesture for yourself alone.” Helen Keller was most profound in her expression: “Never to see the face of a loved one nor to witness a summer sunset is indeed a handicap. But I can touch a face and feel the warmth of the sun. But to be deprived of hearing the song of the first spring robin and the laughter of children provides me with a long and dreadful sadness” (Keller, 1902). Hearing loss is the third most prevalent chronic condition in older Americans and the foremost communicative disorder of older adults. The prevalence of hearing loss is 90% in those older than 80 years. Hearing loss is a common condition in middle-aged adults as well. Estimates are that 20.6% of adults aged 48 to 59 years have impaired hearing. A recent study suggests that cardiovascular disease risk factors may be important correlates of age-related auditory dysfunction. Hearing loss may not be an inevitable part of aging and if detected early, it may be a preventable chronic disease because the same healthy lifestyle changes that improve cardiovascular health may also prevent or delay hearing loss (University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 2011). In all age groups, men are more likely than women to be hearing-impaired. Hearing loss diminishes quality of life and is associated with multiple negative outcomes including decreased function, miscommunication, depression, falls, loss of self-esteem, safety risks, and cognitive decline (Wallhagen and Pettengill, 2008). Hearing impairment increases feelings of isolation and may cause older adults to become suspicious or distrustful or to display feelings of paranoia. Because older persons with a hearing loss may not understand or respond appropriately to conversation, they may be inappropriately diagnosed with dementia. Older people may be initially unaware of hearing loss because of the gradual manner in which it develops (Box 6-2). The Better Hearing Institute (Washington DC) provides an online hearing test for older adults who want to check their own hearing (see http://www.betterhearing.org/hearing_loss/online_hearing_test/index.cfm). Hearing impairment is underdiagnosed and undertreated in older people. Although screening for hearing impairment and appropriate treatment are considered an essential part of primary care for older adults, it is rarely done. A single question—Do you feel you have a hearing loss?—has been shown to have reasonable sensitivity and specificity for hearing impairment (Schumm et al., 2009). Findings of a study performed in 2008 (Box 6-3) suggest that hearing loss is “an overlooked geriatric syndrome in primary care settings—an assessment gap that can have significant negative consequences” (Wallhagen and Pettengill, 2008, p. 41). The screening rate for hearing impairment among older adults is estimated to be as low as 12.9%, and only about 20% of persons with hearing impairments receive hearing aids (Ham et al., 2007; Wallhagen and Pettengill, 2008). Factors associated with lack of hearing aid use include cost, perceived lack of benefit, and denial of hearing loss. Wallhagen (2009) also suggests that the perceived stigma associated with hearing loss and use of hearing aids is another factor that should be examined. The cost of hearing aids is not covered under Medicare and other health plans, but screening for hearing loss is recommended as part of the comprehensive physical for older adults joining Medicare for the first time (Chapter 2). Use of rapid speech when conversing with an older adult with a hearing impairment will make sounds garbled and unintelligible, and even though the problem is related to presbycusis, it is one that is easily remedied. To gain a better understanding of hearing loss, take the Unfair Hearing Test (Sight & Hearing Association, St. Paul, MN), available at http://www.sightandhearing.org/products/knownoise.asp. Sensorineural hearing loss is treated with hearing aids and, in some cases, cochlear implants. Conductive hearing loss usually involves abnormalities of the external and middle ear that reduce the ability of sound to be transmitted to the middle ear. Otosclerosis, infection, perforated eardrum, fluid in the middle ear, or cerumen accumulations cause conductive hearing loss. Cerumen impaction is the most common and easily corrected of all interferences in the hearing of older people. Cerumen impaction has been found to occur in 33% of nursing home residents (Hersh, 2010). Cerumen interferes with the conduction of sound through air in the eardrum. The reduction in the number and activity of cerumen-producing glands results in a tendency toward cerumen impaction. Long-standing impactions become hard, dry, and dark brown. Individuals at particular risk of impaction are African Americans, individuals who wear hearing aids, and older men with large amounts of ear canal tragi (hairs in the ear) that tend to become entangled with the cerumen. When hearing loss is suspected, or a person with existing hearing loss experiences increasing difficulty, it is important first to check for cerumen impaction as a possible cause. If cerumen removal is indicated, it may be removed through irrigation, cerumenolytic products, or manual extraction (Hersh, 2010). Box 6-4 presents a protocol for cerumen removal. Tinnitus generally increases over time. It is a condition that afflicts many older people and can interfere with hearing, as well as become extremely irritating. It is estimated to occur in nearly 11% of elders with presbycusis. Approximately 50 million people in the United States have tinnitus and about 2 million are so seriously debilitated that they cannot function on a “normal,” day to day basis The incidence of tinnitus peaks between ages 65 and 74 and is higher in men than in women; in men, the incidence seems to decrease after this age. Tinnitus is a growing problem for America’s military personnel and is the leading cause of service-connected disability of veterans returning from Iraq or Afganistan (American Tinnitus Association, 2010). The exact physiological cause or causes of tinnitus are not known but there are several likely factors that are known to trigger or worsen tinnitus. Exposure to loud noises is the leading cause of tinnitus and the exposure can damage and destroy cilia in the inner ear. Once damaged, they cannot be renewed or replaced. See http://www.ata.org/for-patients/at-risk#Loud for a video of ways to mitigate noise exposure. Other possible causes of tinnitus include head and neck trauma, certain types of tumors, cerumen build-up, jaw misalignment, cardiovascular disease, and ototoxicity from medications. More than 200 prescription and nonprescription medications list tinnitus as a potential side effect, aspirin being the most common. Tinnitus may be described as pulsatile (matching the beating of the heart) or nonpulsatile (unilateral, asymmetric, or symmetric). Tinnitus may be subjective (audible only to the person) or objective (audible to the examiner). Subjective tinnitus is more common. Objective tinnitus is rare and is frequently due to a vascular or neuromuscular condition. The mechanisms of tinnitus are unknown but have been thought to be analogous to cross-talk on telephone wires, phantom limb pain, or transmission of vascular sounds such as bruits. A simulation of the sounds of tinnitus can be found at http://www.sens.com/helps/demo02/helps_d02_demo_check_2.htm. A hearing aid is a personal amplifying system that includes a microphone, an amplifier, and a loudspeaker. There are numerous types of hearing aids. The behind-the-ear hearing aid looks like a shrimp and fits around and behind the ear. It is less commonly used now than the small, in-the-ear aid, which fits in the concha of the ear (Figure 6-1). The appearance and effectiveness of hearing aids have greatly improved, and many can be programmed to meet specific needs. Most individuals can obtain some hearing enhancement with a hearing aid. It is important for nurses in hospitals and nursing homes to be knowledgeable about the care and maintenance of hearing aids. Many older people experience unnecessary communication problems when in the hospital or nursing home because their hearing aids are not inserted and working properly, or are lost. Box 6-5 presents suggestions for the use and care of hearing aids. Cochlear implants are increasingly being used for older adults who are profoundly deaf as a result of sensorineural hearing loss. A cochlear implant is a small, complex electronic device that consists of an external portion that sits behind the ear and a second portion that is surgically placed under the skin (Figure 6-2). Unlike hearing aids that magnify sounds, the cochlear implant bypasses damaged portions of the ear and directly stimulates the auditory nerve. Hearing through a cochlear implant is different from normal hearing and takes time to learn or relearn. For persons whose hearing loss is so severe that amplification is of little or no benefit, the cochlear implant is a safe and effective method of auditory rehabilitation. Most insurance plans cover the cochlear implant procedure. The transplant carries some risk because the surgery destroys any residual hearing that remains. Therefore, cochlear implant users can never revert to using a hearing aid. Individuals with cochlear implants need to be advised not to undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration advises such individuals “not to even be close to a MRI unit since it may dislodge the implant or demagnetize its internal magnet” (Wallhagen et al., 2006, p. 47). Hearing impairment is common among older adults and significantly affects communication, function, safety, and quality of life. Inadequate communication with older adults with hearing impairment can also lead to misdiagnosis and affect adherence to a medical regimen. The gerontological nurse must be able to assess hearing ability and use appropriate communication skills and devices to help older adults minimize or even avoid problems. The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing (New York, NY) Try This series provides guidelines for hearing screening (see http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_12.pdf). An evidence-based guideline for nursing management of hearing impairment in nursing facility residents is also available (Adams-Wendling and Pimple, 2008). Box 6-6 presents communication strategies for elders with hearing impairment. For older adults, visual problems have a negative impact on quality of life, equivalent to that of life-threatening conditions such as heart disease and cancer. The leading causes of visual impairment are diseases that are common in older adults: age-related macular degeneration (AMD), cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and optic nerve atrophy. Vision loss is becoming a major public health problem and is projected to increase substantially with the aging of the population (National Eye Institute, 2010a). Vision loss from eye disease is a global concern, particularly in the developing countries, where 90% of the world’s blind individuals live. Estimates are that more than 75% of the world’s blindness is preventable or treatable. Vision 2020 is a global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness, launched jointly by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (http://v2020.org/default.asp). Older adults represent the vast majority of the visually impaired population. More than two-thirds of those with visual impairment are over age 65. Although there are no gender differences in the prevalence of vision problems in older adults, there are more visually impaired women than men because, on average, women live longer than men. Racial and cultural disparities in vision impairment are significant. African Americans are twice as likely to be visually impaired than are white individuals of comparable socioeconomic status, and Hispanics also have a higher risk of visual complications than the white population. A recent survey conducted in the United States reported that among all racial and ethnic groups participating in the survey, Hispanic respondents reported the lowest access to eye health information, knew the least about eye health, and were the least likely to have their eyes examined (National Eye Institute, 2008). Estimates of visual impairment among nursing home residents range anywhere from 3 to 15 times higher than for adults of the same age living in the community (Owsley et al., 2007). A study examining the effect of visual impairment among nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease reported that one in three were not using or did not have glasses that were strong enough to correct their vision. They had either lost their glasses or broken them, had prescriptions that were no longer adequate, or were too cognitively impaired to ask for help (Koch et al., 2005). Routine eye care is sorely lacking in nursing homes and is related to functional decline, decreased quality of life, and depression (Owsley et al., 2007). Because visual impairment affects most daily activities, such as driving, reading, maneuvering safely, dressing, cooking, and social activities, assessing the effect of vision changes on functional abilities, safety, and quality of life is most important. Decreased vision has also been found to be a significant risk factor for falls. Results of one study (Rogers and Langa, 2010) suggested that untreated poor vision is associated with cognitive decline, particularly Alzheimer’s disease. Certain signs and behaviors of visual problems that should alert the nurse to action are noted in Box 6-7. A new program focused on vision and aging has been developed by The National Eye Health Education Program (NEHEP) of the National Eye Institute. The program provides health professionals with evidence-based tools and resources that can be used in community settings to educate older adults about eye health and maintaining healthy vision (www.nei.nih.gov/SeeWellToolkit). The program emphasizes the importance of annual dilated eye examinations for anyone over 50 years of age and stresses that eye diseases often have no warning signs or symptoms, so early detection is essential. Clearly, prevention and treatment of eye diseases is an important priority for nurses and other health care professionals. Open-angle glaucoma accounts for about 80% of cases and is asymptomatic until very late in the disease, when there is a noticeable loss in visual fields. However, if detected early, glaucoma can usually be controlled and serious vision loss prevented. Signs of glaucoma can include headaches, poor vision in dim lighting, increased sensitivity to glare, “tired eyes,” impaired peripheral vision, a fixed and dilated pupil, and frequent changes in prescriptions for corrective lenses. Figure 6-3, A shows normal vision and Figure 6-3 B illustrates the effects of glaucoma on vision. Low tension or normal tension glaucoma is a type of glaucoma that also occurs in older adults. In this type, intraocular pressure is within normal range but there is damage to the optic nerve and narrowing of the visual fields. The cause is unknown, but risk factors include a family history of any kind of glaucoma, Japanese ancestry, and cardiovascular disease. Management consists of the same medications and surgical interventions that are used for chronic glaucoma (Glaucoma Research Foundation, 2008). A family history of glaucoma, as well as diabetes, steroid use, and past eye injuries have been noted as risk factors for the development of glaucoma. Age is the single most important predictor of glaucoma, and older women are affected twice as frequently as older men. Among African Americans, glaucoma is the leading cause of blindness. African Americans develop glaucoma at younger ages, and the incidence of the disease is five times more common in African Americans than in whites and fifteen times more likely to cause blindness. Factors contributing to this increased incidence include earlier onset of the disease as compared with other races, later detection of the disease, and economic and social barriers to treatment (National Eye Institute, 2010b). Management of glaucoma involves medications (oral or topical eye drops) to decrease IOP and/or laser trabeculoplasty. Medications lower eye pressure either by decreasing the amount of aqueous fluid produced within the eye or by improving the flow through the drainage angle. Beta blockers are the first-line therapy for glaucoma, and the patient may need combinations of several types of eye drops. When caring for older adults in the hospital or long-term care settings, it is important to obtain a past medical history to determine if the person has glaucoma and to ensure that eye drops are given according to the person’s treatment regimen. Without the eye drops, eye pressure can rise and cause an acute exacerbation of glaucoma (Capezuti et al., 2008). Usually medications can control glaucoma, but laser surgery treatments (trabeculoplasty) may be recommended for some types of glaucoma. Surgery is usually recommended only if necessary to prevent further damage to the optic nerve. Cataracts are recognized by the clouding of the ordinarily clear ocular lens; the red reflex may be absent or may appear as a black area. The cardinal sign of cataracts is the appearance of halos around objects as light is diffused. Other common symptoms include blurring, decreased perception of light and color (giving a yellow tint to most things), and sensitivity to glare. Figure 6-3, C illustrates the effects of a cataract on vision. The most common causes of cataracts are heredity and advancing age. They may occur more frequently and at earlier ages in individuals who have been exposed to excessive sunlight, have poor dietary habits, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, eye trauma, or history of alcohol intake and tobacco use. Cataracts are more likely to occur after glaucoma surgery or other types of eye surgery. There is some evidence that a high dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin, compounds found in yellow or dark leafy vegetables, as well as intake of vitamin E from food and supplements, appears to lower the risk of cataracts in women. Further research is indicated (Moeller et al, 2008). Although race is not a factor in cataract formation, racial disparities exist in cataract surgery in the United States, with African-American Medicare recipients only 60% as likely as whites to undergo cataract surgery (Miller, 2008; Wilson and Eezzuduemhoi, 2005). Cataracts are of even greater concern in Africa and Asia and account for at least half of the blindness in those countries despite the well known technology that can restore vision at an extremely low cost. Recommendations from Vision 2020 include reducing the backlog of the cataract-blind by increased training of ophthalmic personnel, strengthening of the health care infrastructure, and provision of needed surgical supplies in these countries (www.who.int/ncd/vision2020_actionplan/documents/V2020priorities.pdf2004).

Communicating with Older Adults

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Ageism and Communication

Elderspeak

Communicating with Older Adults with Sensory Impairments

Hearing Impairment

Types of Hearing Loss

Tinnitus

Assessment

Interventions to Enhance Hearing

Hearing Aids

Cochlear Implants

Promoting Healthy Aging: Implications for Gerontological Nursing

Vision Impairment

Diseases of the Eye

Glaucoma

Screening and Treatment

Cataracts

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access