Communicating with Children and Families

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe components of effective communication with children.

• Describe communication strategies that assist nurses in working effectively with children.

• Explain the importance of avoiding communication pitfalls in working with children.

• Describe effective family-centered communication strategies.

• Describe effective strategies for communicating with children with special needs.

• Describe warning signs of overinvolvement and underinvolvement in child/family relationships.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

To work effectively with children and their families, nurses need to develop keen communication skills. Because parents and other family members play a crucial role in the lives of children, nurses need to establish rapport with the family in order to identify mutual goals and facilitate positive outcomes. An awareness of body language, eye contact, and tone of voice must accompany good verbal communication skills when one is listening to children and their families. The same awareness helps nurses assess their own communication styles.

Components of Effective Communication

Communication is much more than words going from one person’s mouth to another person’s ears. In addition to the words themselves, the tone and quality of voice, eye contact, physical proximity, visual cues, and overall body language convey messages. These nonverbal communications are often undervalued, yet comprise a significant portion of total communication. In choosing communication techniques to be used with children and families, the nurse considers cultural differences, particularly with regard to touch and personal space (see Chapter 3). Communication provides an important linkage between parents and providers that is based on honesty, caring, respect, and a direct approach (Fisher & Broome, 2011). Good communication is key to the identification of health issues, adherence to a treatment plan, and improved psychological and behavioral outcomes (Levetown, 2008). Optimal communication addresses both the cognitive and emotional needs of children and families (Levetown, 2008).

Touch

Touch can be a positive, supportive technique that is effective from birth through adulthood. Touch can convey warmth, comfort, reassurance, security, trust, caring, and support.

In infancy, messages of love, security, and comfort are conveyed through holding, cuddling, gentle stroking, and patting. Infants do not have cognitive understanding of the words they hear, but they sense the emotional support, and they can feel, interpret, and respond to gentle, loving, supportive hands caring for them. Toddlers and preschoolers find it soothing and comforting to be held and rocked, as well as stroked gently on the head, back, arms, and legs (Figure 4-1).

Touch is a powerful means of communicating. Toddlers and preschoolers often find touch in the form of cuddling and stroking to be soothing. Even older children who prize their independence find that a parent’s hug or pat on the back helps them feel more secure. A child can communicate more easily with a nurse who is at eye level and at a comfortable conversational distance. The nurse may need to squat or even sit on the floor to talk with very young children.

School-age children and adolescents appreciate giving and receiving hugs and getting a reassuring pat on the back or a gentle hand on the hand. The nurse, however, needs to request permission for any contact beyond a casual touch with these children.

Physical Proximity and Environment

Children’s familiarity and comfort with their physical surroundings affect communication. Normally, children are most at ease in their home environments. Once they enter a clinic, emergency department, or patient care unit, they are in an unfamiliar environment, and they experience heightened anxiety. Hospital and clinic staff members have a tremendous advantage in knowing their clinic or unit as a familiar workplace. Nurses can gain a better picture of what a child is experiencing by trying to place themselves in the child’s position and imagining the child’s first impression of the triage desk, the reception desk, the admitting office, the treatment room, and the hospital room. A child’s perspective is probably very different from an adult’s. Creating a supportive, inviting environment for children includes the use of child-size furniture, colorful banners and posters, developmentally appropriate toys, and art displayed at a child’s eye level.

Individuals have different comfort zones for physical distance. The nurse should be aware of differences and should move cautiously when meeting new children and families, respecting each individual’s personal space. For example, standing over the child and family can be intimidating. Instead, the nurse should bring a chair and sit near the child and family. This action puts the nurse at eye level. If a chair is not accessible, the nurse may stoop or squat. The important part is to be at eye level while remaining at a comfortable distance for the child and family (Figure 4-2).

The nurse should not overlook privacy or underestimate its importance. A room should be available for conducting private conversations away from roommates or family members and visitors. Privacy is particularly critical in working with adolescents, who typically will not discuss sensitive topics with parents present. The nurse’s skill and ease with parents of adolescents will increase the adolescents’ trust in the nurse. Nurses need to avoid hallway conversations, particularly outside a child’s room, because children and parents may overhear only some words or phrases and misinterpret the meaning. Overhearing may lead to unnecessary stress and mistrust between the health care providers and the child or family.

Listening

Messages given must be received for communication to be complete. Therefore, listening is an essential component of the communication process. By practicing active listening skills, nurses can be effective listeners. Active listening skills are as follows:

Attentiveness

The nurse should be intentional about giving the speaker undivided attention. Eliminating distractions whenever possible is important. For example, the nurse should maintain eye contact, close the room door, and eliminate potential distractions (e.g., television, computer, video games, smartphones).

Clarification through Reflection

Using similar words, the nurse expresses to the speaker what was heard and understood about the content of the message. For example, when the child or family member says, “I hate the food that comes on my tray,” a reflective response would be, “When you say you are unhappy with the food you’ve been given, what can we do to change that?” As the conversation progresses, the nurse can move the child through a dialogue that identifies those nutritional foods the child would eat.

Empathy

The nurse identifies and acknowledges feelings expressed in the message. For example, if a child is crying after a procedure, the nurse might say, “I know it is uncomfortable to have this procedure. It is okay to cry. You did a great job holding still.”

Impartiality

To understand and avoid prejudicing what is heard with personal bias, the nurse listens with an open mind. For example, if a young adolescent shares that she is sexually active and is mainly concerned about sexually transmitted diseases, the nurse remains a supportive listener. The nurse can then provide her with educational materials and resources as well as discuss the possible outcomes of her actions in a manner that is open and not judgmental, regardless of the nurse’s personal values and beliefs.

During shift handoff, descriptions of family must be shared objectively and impartially. Otherwise, perceptions of families may negatively affect how colleagues approach and interact with families.

To enhance the effectiveness of communication and maximize normal language patterns that contribute to language development, the nurse focuses on talking with children rather than to them and develops conversations with children.

The nurse must be prepared to listen with the eyes as well as the ears. Information will not always be audible, so the nurse must be alert to subtle cues in body language and physical closeness. Only then can one fully understand the messages of children. For example, when the nurse enters the room to complete an initial assessment of a 4-year-old child and observes the child turning away and beginning to suck her thumb, the child is communicating about her basic security and comfort level, although she has not said a word.

Visual Communication

Eye contact is a communication connector. Making eye contact helps confirm attention and interest between the individuals communicating. Direct eye contact may be uncomfortable, however, for people in some cultures, so the nurse needs to be sensitive to responses when making eye contact.

Clothing, physical appearance, and objects being held are visual communicators. Children may react to an individual’s presence on the basis of a white lab coat, a bushy beard, or a syringe or video game in the hand. The nurse needs to think ahead and anticipate visual stimuli a child may find startling and those that may be pleasing and to make appropriate adjustments when possible. For example, it is a routine practice for nurses to bring a medication in a syringe for insertion into an intravenous (IV) line. Unless the purpose of the syringe is immediately explained, children might quickly assume they are about to receive an injection.

Some children, and some adults, are visual learners. They learn best when they can see or read instructions, demonstrations, diagrams, or information. Using various methods of presenting and sharing information will increase comprehension for such children.

Concepts can be presented more vividly by using developmentally appropriate photographs, videos, dolls, computer programs, charts, or graphs than by using written or spoken words alone. The nurse needs to select teaching tools and materials that appropriately match the child’s growth and developmental level.

Tone of Voice

The spoken word comes to mind most often when communication is the topic. Communication, however, consists of not only what is said but also the way it is said. The tone and quality of voice often communicate more than the words themselves.

Because infants’ cognitive understanding of words is limited, their understanding is based on tone and quality of voice. A soft, smooth voice is more comforting and soothing to infants than a loud, startling, harsh voice. Infants can sense from the tone of voice whether the caregiver is angry or happy, frustrated or calm. The nurse can assess how aware of and sensitive to these messages infants are by observing their body language. Infants are relaxed when they hear a calm, happy caregiver and tense and rigid when they hear an angry, frustrated caregiver.

Children can detect anger, frustration, joy, and other feelings that voices convey, even when the accompanying words are incongruent. This incongruity can be very confusing for children. The nurse should strive to make words and their intended meanings match.

Verbal communication extends beyond actual words. All audible sounds convey meaning. An infant’s primary mode of audible communication is crying. Crying is a cue to check basic needs, including hunger, pain, discomfort (e.g., wet diaper), and temperature. Cooing and babbling, also heard during the first year of life, generally convey messages of comfort and contentment. As children develop and mature, they have larger vocabularies to express their ideas, thoughts, and feelings.

The choice of words is critical in verbal communication. The nurse needs to avoid talking down to children but should not expect them to understand adult words and phrases. Technical health care terms should be used selectively, and jargon should be avoided (see Table 4-4).

Body Language

From the gentle caress of holding an infant to sitting and listening intently to an adolescent’s story, body language is a factor in communication. An open body stance and positioning invite communication and interaction, whereas a closed body stance and positioning impede communication and interaction.

Using an open body posture improves the nurse’s understanding of children and the children’s understanding of the nurse. Nurses need to learn to read children’s body language and should become more aware of their own body language. Table 4-1 compares open and closed body postures.

TABLE 4-1

| OPEN | CLOSED |

| Leaning toward other person | Leaning away from other person |

| Arms loose at sides | Arms folded across chest |

| Frequent eye contact | No eye contact |

| Hands moving freely | Hands on hips |

| Soft stance, body swaying slightly | Rigid stance |

| Head up | Head bowed |

| Calm, slow movements | Constant motion, squirming |

| Smiling, friendly facial cues | Frowning, negative facial cues |

| Conversing at eye level | Conversing at a level that requires the child to move to listen |

Timing

Recognizing the appropriate time to communicate information is a developed skill. A distraught child whose parents have just left for work is not ready for a diabetic teaching session. The session will be much more productive and the information better understood if the child has a chance to make the transition. The convenience of meeting a schedule should be secondary to meeting a child’s needs.

In the well or outpatient setting, scheduling teaching sessions that adapt to a parent’s schedule can enhance child’s or parent’s understanding of information (Li & Chung, 2009). For example, scheduling a teaching session during the late afternoon or early evening, or on a Saturday, at the parent’s convenience assures increased attention because the parent is not distracted with needing to be at work or other demands on time.

Family-Centered Communication

Any discussion about effective ways to communicate with children must also include a discussion of effective communication with families. Family-centered care emphasizes that the family is intimately involved in the care of the child. Parents need to be supported while sustaining their parental role during their child’s hospitalization (Sanjari, Shirazi, Heidari, et al., 2009). Family-centered care is achieved when health care professionals can create partnerships with families, recognizing that the family is essential to the child and that the family has the right to participate fully in planning, implementing, and evaluating the child’s plan of care.

Commitment to family-centered care means that the nurse respects the family’s diversity. Children and parents live in a variety of family structures. An expanded definition of family is required in the twenty-first century, because the term no longer refers to only the intact, nuclear family in which parents raise their biologic children. Contemporary family structures include adolescent parents; extended families with aunts, uncles, or cousins parenting; intergenerational families with grandparents parenting; blended families with stepparents and stepsiblings; gay or lesbian parents; foster parents; group homes; and homeless children. The nurse should be prepared to identify the foundational strengths in all family structures (see Chapter 3). Family-centered care also means that the nurse truly believes that the child’s care and recovery are greatly enhanced when the family fully participates in the child’s care (Figure 4-3).

The nurse explains a child’s test results to his mother and grandmother. Including all important family members in the child’s health care reflects commitment to family-centered care. (Courtesy University of Texas at Arlington College of Nursing, Arlington, TX.) This nurse practitioner has learned Spanish to communicate better with her many Spanish-speaking patients. Speaking with family members in their own language encourages the family to remain in the health care system. The nurse is also using eye contact and has positioned herself at the mother’s eye level. (Courtesy Parkland Health and Hospital System Community Oriented Primary Care Clinic, Dallas, TX.)

Establishing Rapport

Critical to establishing rapport with families is the nurse’s ability to convey genuine respect and concern during the first encounter. A nonjudgmental approach and a willingness to assist family members in effectively caring for their child demonstrate the nurse’s interest in their well-being.

Availability and Openness to Questions

A nurse who does not take time to see how a child and family are doing—such as a nurse who leaves a room immediately after a treatment or administration of a medication—will not encourage or invite families to ask questions. Families want and need unrushed and uninterrupted time with the nurse. Sometimes this time can be made available only by purposefully scheduling it into the day. Encouraging families to write down their questions will enable them to take full advantage of their time with the nurse.

Family Education and Empowerment

Family empowerment occurs when the nurse and other health providers take the time to educate parents about their child’s condition and the skills needed to participate, thus ensuring their continued involvement in planning and evaluating the plan of care. Families need support as they gain confidence in their skills, and they need guidance to assist them as they navigate through the health care experience. Communication is enhanced when families feel competent and confident in their abilities.

Effective Management of Conflict

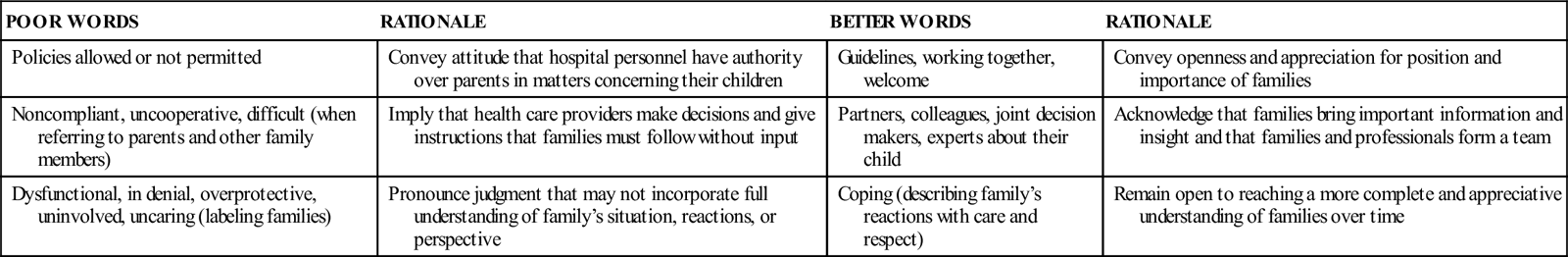

When conflict occurs, it needs to be addressed in an expedient manner to prevent further breakdown in communication. Box 4-1 suggests strategies for managing conflict, and Table 4-2 highlights the importance of choosing words carefully to make families feel welcome and to further facilitate family-centered care.

TABLE 4-2

| POOR WORDS | RATIONALE | BETTER WORDS | RATIONALE |

| Policies allowed or not permitted | Convey attitude that hospital personnel have authority over parents in matters concerning their children | Guidelines, working together, welcome | Convey openness and appreciation for position and importance of families |

| Noncompliant, uncooperative, difficult (when referring to parents and other family members) | Imply that health care providers make decisions and give instructions that families must follow without input | Partners, colleagues, joint decision makers, experts about their child | Acknowledge that families bring important information and insight and that families and professionals form a team |

| Dysfunctional, in denial, overprotective, uninvolved, uncaring (labeling families) | Pronounce judgment that may not incorporate full understanding of family’s situation, reactions, or perspective | Coping (describing family’s reactions with care and respect) | Remain open to reaching a more complete and appreciative understanding of families over time |

Feedback from Children and Families

The nurse needs to be alert for both verbal and nonverbal cues. Routinely checking with family members about their experiences, satisfaction with communications, teaching sessions, and health care goals is an effective way to ensure that health care providers obtain appropriate feedback. To enhance the delivery of care, the nurse should explain how this feedback will be used. The nurse should listen and observe carefully to make sure that what family members are saying is truly what they are feeling.

Transparent communication between parents and nurses is integral to providing family-centered care (McCann, Young, Watson, et al., 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree