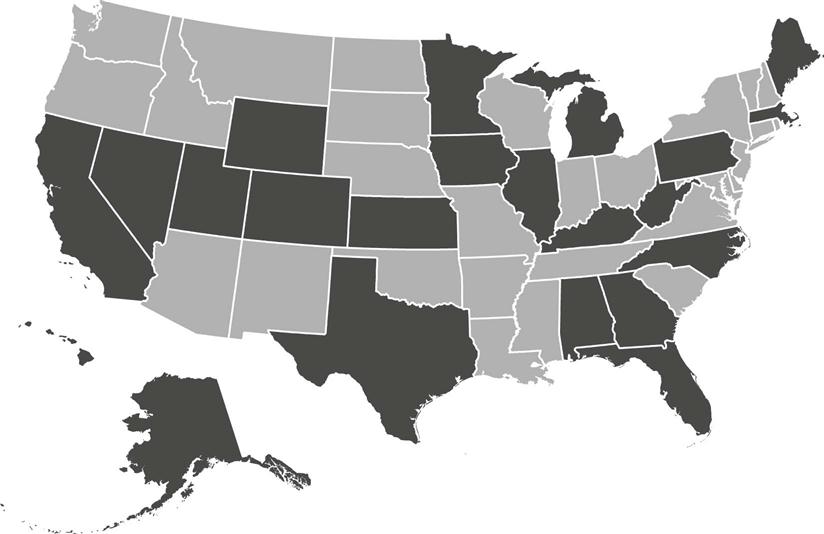

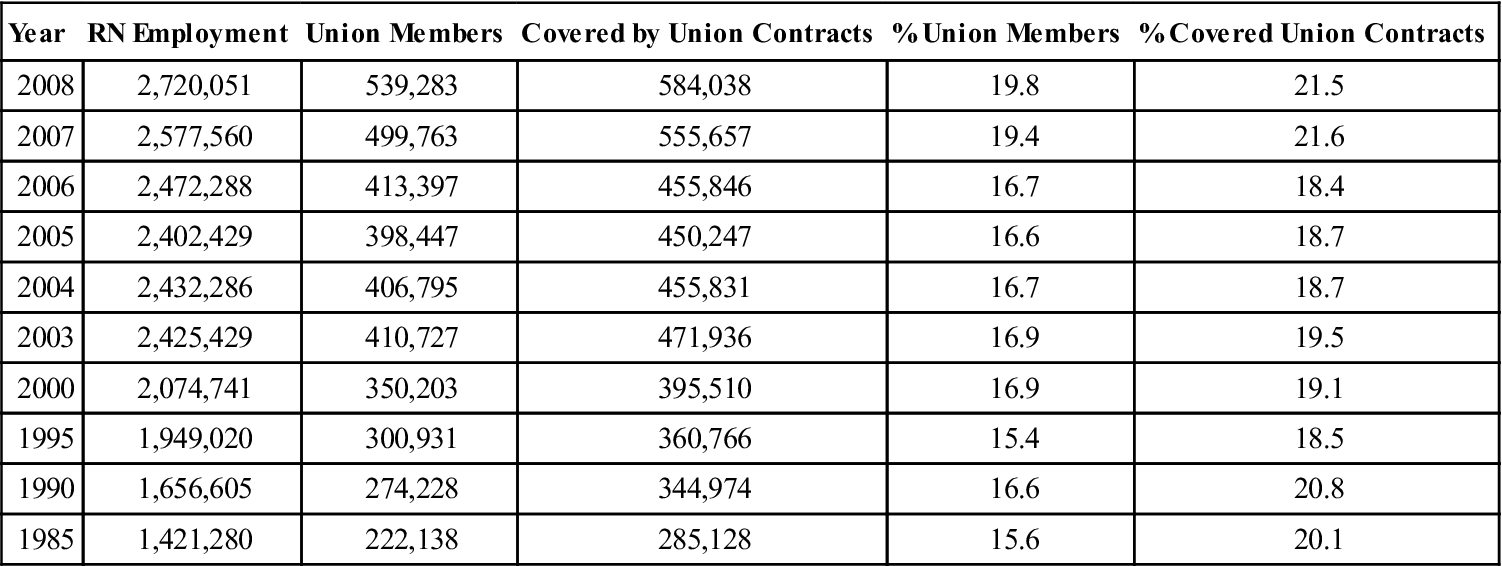

Judith Shindul-Rothschild “Unions provide nurses with real power to protect their practice and their profession.” —Donna Kelly-Williams, RN, President of Massachusetts Nurses Association, March 2010 The number of registered nurses covered under collective bargaining agreements in the United States has been steadily rising since 2004 to 21.5% and is higher than for all U.S. workers (13.7%) and women in the workforce (12.9%) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009) (Table 61-1). In 2008, approximately 17% of all U.S. hospital workers were covered by a union contract (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). The three largest unions in the U.S. that represent registered nurses for collective bargaining are as follows: • National Nurses United (NNU) is the largest union, representing over 150,000 registered nurses (Figure 61-1). • Service Employees International Union (SEIU) represents 80,000 registered nurses. • National Federation of Nurses (NFN) has 70,000 registered nurse members. TABLE 61-1 Registered Nurse Employment in the U.S., Union Membership or Covered by Union Contracts, 1985-2008 Adapted from Hirsch, B. T., & Macpherson, D. A. (2010). V. Occupation: Union membership, coverage, density and employment by occupation, 2008-1985. Union membership and coverage database from the current population survey. The NNU and SEIU are members of the AFL-CIO, while the NFN is associated with the American Nurses Association. When the first nursing organizations were formed at the turn of the twentieth century, one of the central concerns was the exploitation of student nurses. After 6 months of coursework, it was common practice for student nurses to provide 3 years of unpaid labor working 12 to 16 hours a day. And yet surprisingly, in 1911, nursing organizations opposed the first labor legislation limiting the hours student nurses worked. Such contradictions would reappear throughout the history of collective bargaining in nursing. Should nurses be aligned with the labor movement, or eschew any association with labor because it would diminish nursing’s professional status? Would it be possible for one professional nursing organization to address professional advancement and workplace advocacy? While professional nursing organizations struggled with the philosophical view that any association with the labor movement would diminish nursing’s aspirations to advance their professional status, rank-and-file nurses were participating in strikes in response to inhumane working conditions as early as the 1900s. The original National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) enacted in 1935, mandated the right of hospital employees to collective bargaining. However, several actions, both by government and by nurses themselves, would hamper nurses’ use of collective bargaining to improve their working lives. In 1947, the American Hospital Association persuaded Congress to include a clause in the Taft-Hartley Amendments to exempt private nonprofit hospitals from the National Labor Relations Act—a clause that remained in effect until 1974. Shortly thereafter, the membership of the American Nurses Association adopted a no-strike policy to quell fears that striking nurses would abandon their patients. In the face of these impediments, by the 1950s only 17 state nurses’ associations had programs in place to represent registered nurses in collective bargaining activities. Organized nursing’s ambivalence toward the labor movement began to shift in the second half of the 1900s when low salaries and poor working conditions created persistent nursing shortages. By the 1960s, the civil rights movement and the women’s liberation movement set the stage for nurses nationwide to embrace collective bargaining as a potent means to improve their professional and working lives. In the summer of 1966, registered nurses represented by the California Nurses Association (CNA) in 33 San Francisco hospitals submitted their resignations in response to the hospital association’s failure to address nurses’ deteriorating salaries. The unprecedented collective action by the CNA nurses forced hospital administrators to concede to the nurses’ demands including a 40% pay increase. Emboldened by the success of the California nurses, registered nurses began to stage work stoppages throughout the United States. By the time nurses arrived at the annual ANA convention in 1968, they came prepared to vote down ANA’s 18-year-old no-strike policy. State associations soon followed the ANA’s lead as they too abolished their policy of prohibiting strikes by nurses. Now, equipped with the necessary leverage to make collective bargaining effective, nurses quickly began to organize. Registered nurses grew to support unions because of the measurable impact collective bargaining had on both salaries and working conditions. Early collective bargaining agreements addressed the traditional bread-and-butter issues of organized labor by establishing a 40-hour workweek, time and a half for overtime, paid vacation and sick leave, health insurance benefits, disability benefits, pensions, and salary increases. By 1969, nurses’ salaries had surpassed the average income for female professionals and in response, vacancy rates in hospitals dropped for the first time into single digits (Aiken & Blendon, 1981). Labor economists uniformly concluded that collective bargaining was the major factor that forced hospitals to increase nurses’ wages and drew thousands of nurses back into the labor force during critical shortages in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Yett, 1975; Feldstein, 1979). Beginning in the early 1980s, pay equity and staffing agreements began to appear in collective bargaining agreements. To redress pay disparities between men and women, the Florida, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New York, and California Nursing Associations included comparable worth provisions—equal pay for performing work of comparable value, responsibility, and complexity—in all collective bargaining contracts. Language was negotiated in collective bargaining agreements requiring the participation of staff nurses in staffing decisions and the use of patient acuity systems to determine appropriate staffing levels. The California Nurses Association successfully lobbied for state regulations establishing RN-to-patient ratios in intensive care units. The professional and economic gains achieved by nurses in the 1980s through collective bargaining were often hard fought. In Massachusetts alone, nurses went on strike in eight hospitals to demand provisions in labor contracts that would improve the quality of patient care as well as wages (Wilson, Slatin, & O’Sullivan, 2006). Nurses’ professional and economic gains were again challenged beginning in 2000 by cost-cutting measures that threatened the welfare of nurses and their ability to provide safe patient care. Inadequate nurse staffing triggered a widespread practice of mandatory overtime in hospitals nationwide. Frustrated with the lack of responsiveness by hospital administrators and policymakers to unsafe staffing and inhumane working conditions, unions used their leverage in labor negotiations and in state legislatures to secure a series of reforms (Shindul-Rothschild, 1998) (Box 61-1).

Collective Bargaining in Nursing

Year

RN Employment

Union Members

Covered by Union Contracts

% Union Members

% Covered Union Contracts

2008

2,720,051

539,283

584,038

19.8

21.5

2007

2,577,560

499,763

555,657

19.4

21.6

2006

2,472,288

413,397

455,846

16.7

18.4

2005

2,402,429

398,447

450,247

16.6

18.7

2004

2,432,286

406,795

455,831

16.7

18.7

2003

2,425,429

410,727

471,936

16.9

19.5

2000

2,074,741

350,203

395,510

16.9

19.1

1995

1,949,020

300,931

360,766

15.4

18.5

1990

1,656,605

274,228

344,974

16.6

20.8

1985

1,421,280

222,138

285,128

15.6

20.1

A Brief History of Collective Bargaining in Nursing

Collective Bargaining and Legislative Initiatives Since 2000

Collective Bargaining in Nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access