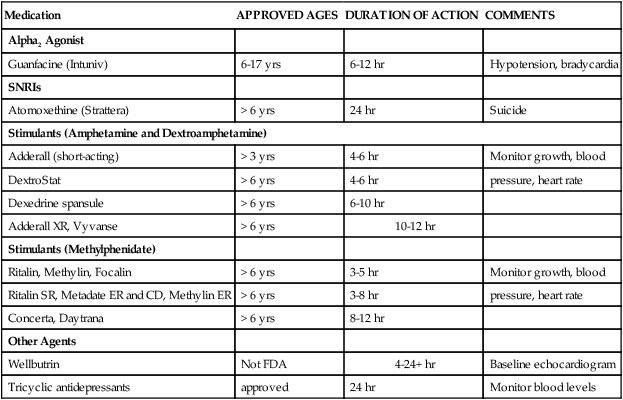

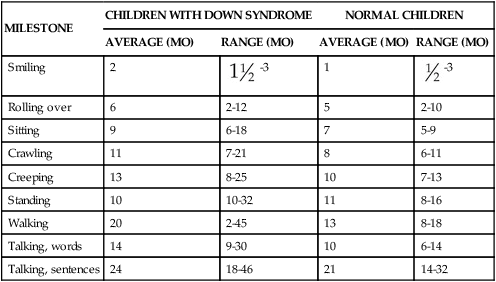

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Demonstrate a positive attitude when caring for developmentally disabled children and their families 3. Relate the symptoms of a child with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder with corresponding social, educational, and emotional difficulties and describe strategies to help the child and family cope with the condition 4. Summarize the different characteristics that would be found in Down syndrome 5. Define the characteristics of infants with failure to thrive 6. List four kinds of child abuse, and describe the behaviors often exhibited by parent and child in each case 7. Discuss care of the hospitalized autistic child 8. Contrast the clinical presentation and nursing care of the teenager with anorexia nervosa with that of the teenager with bulimia 9. Identify health issues for substance abuse drugs 10. List four risk factors that might indicate an adolescent is contemplating suicide There are several terms associated with cognitive impairment. A developmental disability is any mentally or physically disabling condition that begins during childhood and is expected to continue throughout life. This includes children with issues such as mental retardation, sensory deficits (speech, hearing, vision), orthopedic problems, and other conditions including autism and cerebral palsy. The term for mental retardation has been changed to intellectual disability to conform with the name change for the American Association of Mental Retardation (AAMR) to American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005) states, “intellectual disability is characterized both by a significantly below-average score on a test of mental ability or intelligence and by limitations in the ability to function in areas of daily life, such as communication, self-care, and getting along in social situations and school activities.” It requires a multidimensional approach; with appropriate support, the life of the person with an intellectual disability generally improves. Many children with intellectual disabilities may have additional disabilities such as hearing loss, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Intellectual disability affects 2% to 3% of the population. According to Kliegman and colleagues (2007), there are two overlapping populations of intellectually disabled children. There are those with mild intellectual disability, which is associated with environmental influences, and those with severe intellectual disability, which is associated more with biological causes. Some persons have a congenital malformation of the brain; others have had damage to the brain at a critical period in prenatal or postnatal development. Conditions that can develop during the prenatal period include PKU, Down syndrome, fetal alcohol syndrome, malformations of the brain (such as microcephaly, hydrocephalus, craniosynostosis), maternal infections, and anoxia. Birth injuries or anoxia during or shortly after delivery can also cause intellectual disability. Diseases such as meningitis, lead poisoning, neoplasms, and encephalitis can cause intellectual disability in a child or adult at any age. Other causes include near-drowning and traumatic brain injury. Heredity is a factor in intellectual disability. It is also possible for children to live in such a physically and emotionally deprived environment that they develop intellectual disability. Approximately 40 to 50% of the causes have no identifiable cause (AAIDD, 2009). The Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-II) is used for children 1 to 3 years of age. It assesses language, visual problem-solving skills, behavior, and fine- and gross-motor skills. Tests for adaptive behavior include the Wechsler Scales for children 3 years and older and the Woodcock-Johnson Scales (Kliegman et al., 2007). There is usually good correlation between tests for intelligence and adaptive behavior. It is important that nurses be familiar with the resources in their communities so that they can direct the family to them. The local chapter of The Arc (www.thearc.org) can provide information and support. The child guidance clinic or the psychological services of a nearby college or hospital may provide beneficial assistance. The visits of the public health nurse are invaluable in many cases. Children also may be eligible to obtain help from their local vocational and rehabilitation agency. Respite care workers afford needed rest and increased mobility for parents. In some communities, parent groups meet to discuss mutual problems. Arrangements for proper dental health must be made. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has repeatedly tried to precisely define and categorize symptoms of ADHD. With its most current DSM-IV-TR criteria, the Association identifies three major patterns of the disorder: (1) ADHD, predominantly inattentive type; (2) ADHD, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type; and (3) ADHD, combined (American Psychiatric Association, 2004). Symptoms must be present for at least 6 months, must have appeared before 7 years of age, must be identified in more than one setting (home, school), and must cause significant impairment in psychosocial or educational adjustment and functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2004). In addition, other causes for the behavior must be ruled out before a diagnosis can be made. The following are some manifestations that suggest ADHD: • Is inattentive to details, careless with schoolwork or other activities • Has difficulty organizing tasks • Is unable to sustain attention for periods of time that would be appropriate for age • Does not listen, follow instructions, or complete tasks; interrupts frequently • Avoids activities and games that require concentration • Appears to have excessive energy • Fidgety, cannot remain seated • Cannot play quietly, excessive talking • Blurts out answers and interrupts • Difficulty with social situations The ideal approach to ADHD is a combination of medications and behavioral treatment. Medications are appropriate first-line treatment for children except for preschoolers (ages 4 to 6). Behavioral therapy or parent-training programs should be considered for the preschooler. There are four categories of medications that are approved for use in children. Stimulants, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), alpha-2 agonists, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are all FDA-approved (Table 20-1). Table 20-1 In addition to medications, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends the use of behavior therapy. Programs may use training sessions with a trained therapist in behavior modification. The goal of this approach is to assist the parents in understanding the child’s behavior and learning specific techniques for altering behavior (Katragadda and Schubiner, 2007). Prenatal testing can be done in the first or third trimester. It includes serum and ultrasound testing, with specific diagnosis using amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that all women be offered aneuploidy screening before 20 weeks of gestation and that all women have the option of invasive testing (ACOG, 2007). The signs of this condition, which are apparent at birth, are close-set and upward-slanting eyes, small head, round face, flat nose, mouth breathing, and a protruding tongue that interferes with sucking. The hands of the infant are short and thick, and the little finger is curved. In addition, there is a deep, straight line across the palm, called the simian crease (Figure 20-1). There is also a wide space between the first and second toes. Undeveloped muscles (hypotonia) and loose joints enable the child to assume unusual positions. Physical growth and development may be slower than normal (Table 20-2 and Home Care Considerations box). Most children are mildly to moderately intellectually challenged. Because of recent advances in medicine, education, and available resources, these children are able to progress further than previously possible. Many additional medical issues can accompany Down syndrome. Congenital heart deformities, gastrointestinal disorders (imperforate anus, esophageal atresia, celiac disease), pulmonary hypertension, ENT anomalies, endocrine disease (thyroid), immune dysfunction, hematologic disorders (polycythemia, leukemia), and psychiatric issues (dementia, Alzheimer’s) can all be issues for the child with Down syndrome. It is important to remember that no one child exhibits all the possible physical characteristics of Down syndrome. Table 20-2 From Carey W., Crocker, A., Elias, E., et al. (2009). Developmental-behavioral pediatrics (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders, with permission.

Cognitive and Behavior Disorders

Overview of Cognitive and Behavior Disorders

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

Treatment and Nursing Care

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Signs and Symptoms

Treatment and Nursing Care

Medication

APPROVED AGES

DURATION OF ACTION

COMMENTS

Alpha2 Agonist

Guanfacine (Intuniv)

6-17 yrs

6-12 hr

Hypotension, bradycardia

SNRIs

Atomoxethine (Strattera)

> 6 yrs

24 hr

Suicide

Stimulants (Amphetamine and Dextroamphetamine)

Adderall (short-acting)

> 3 yrs

4-6 hr

Monitor growth, blood

DextroStat

> 6 yrs

4-6 hr

pressure, heart rate

Dexedrine spansule

> 6 yrs

6-10 hr

Adderall XR, Vyvanse

> 6 yrs

10-12 hr

Stimulants (Methylphenidate)

Ritalin, Methylin, Focalin

> 6 yrs

3-5 hr

Monitor growth, blood

Ritalin SR, Metadate ER and CD, Methylin ER

> 6 yrs

3-8 hr

pressure, heart rate

Concerta, Daytrana

> 6 yrs

8-12 hr

Other Agents

Wellbutrin

Not FDA

4-24+ hr

Baseline echocardiogram

Tricyclic antidepressants

approved

24 hr

Monitor blood levels

Down Syndrome

Signs and Symptoms

MILESTONE

CHILDREN WITH DOWN SYNDROME

NORMAL CHILDREN

AVERAGE (MO)

RANGE (MO)

AVERAGE (MO)

RANGE (MO)

Smiling

2

-3

-3

1

-3

-3

Rolling over

6

2-12

5

2-10

Sitting

9

6-18

7

5-9

Crawling

11

7-21

8

6-11

Creeping

13

8-25

10

7-13

Standing

10

10-32

11

8-16

Walking

20

2-45

13

8-18

Talking, words

14

9-30

10

6-14

Talking, sentences

24

18-46

21

14-32

Cognitive and Behavior Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access