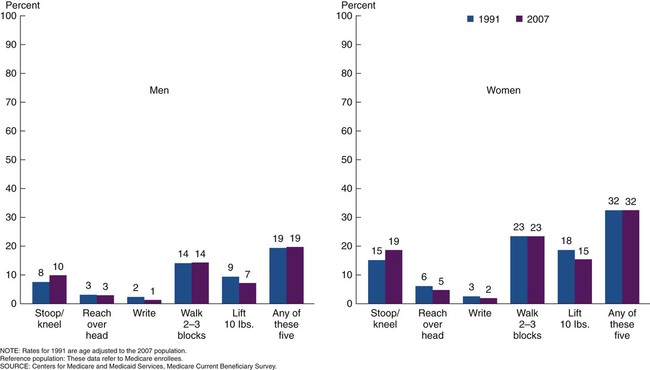

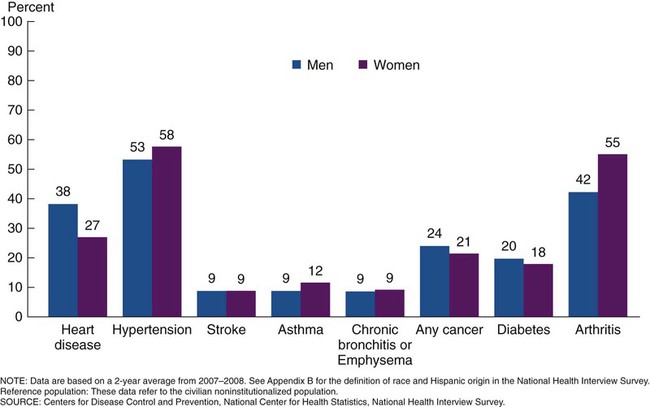

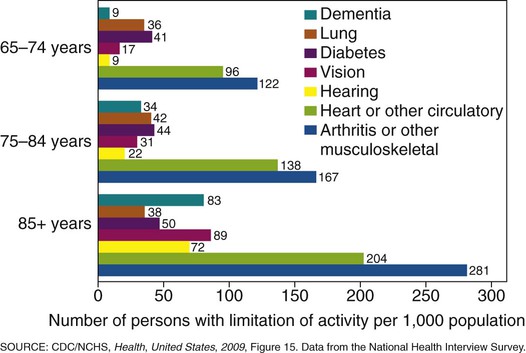

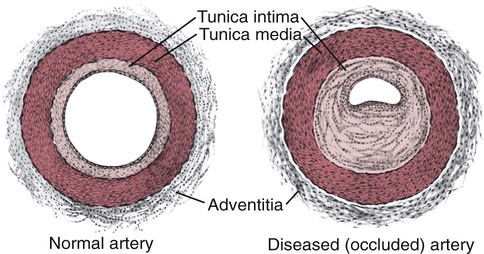

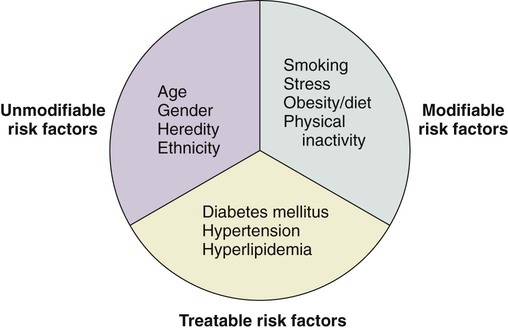

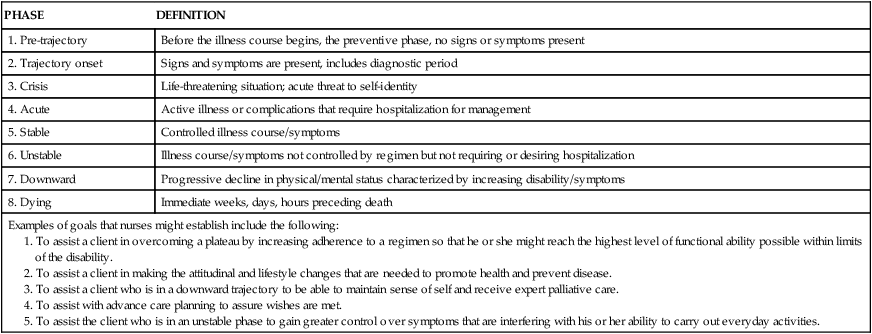

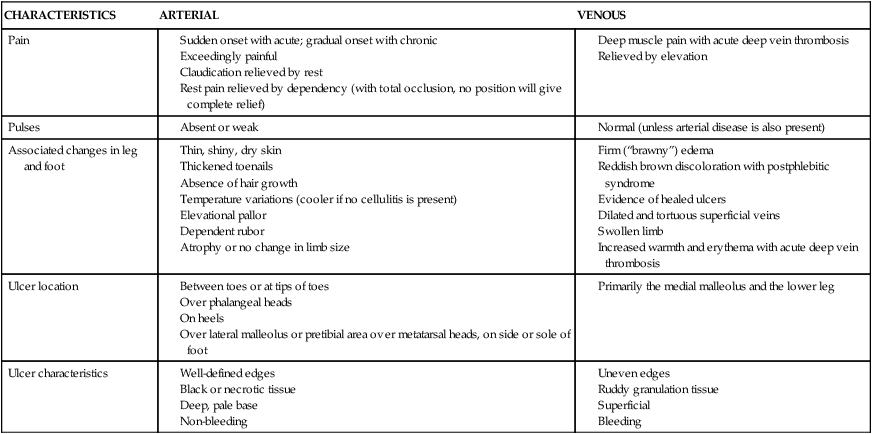

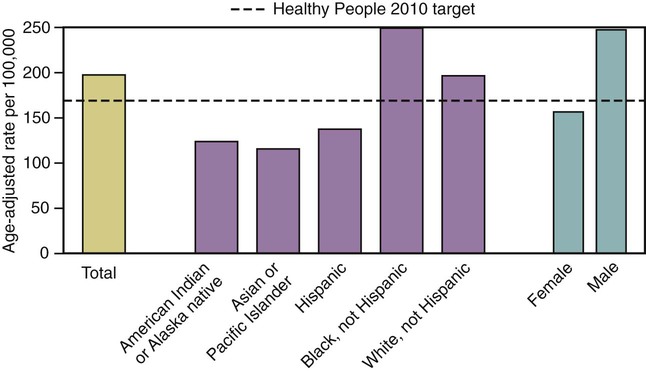

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify the most common chronic disorders of late life and their sequela. 2. Develop strategies that have been used successfully to maintain maximum function and comfort in the person with a chronic disorder. 3. Suggest nursing interventions appropriate to the care of an individual with a chronic disorder. 4. Construct nursing interventions that are consistent with a theoretical framework of maximizing wellness in the presence of chronic disease. The relationship between chronic disease and aging is complex. Chronic disease, such as heart failure, was once viewed intrinsic to aging. This belief was challenged as the science of preventive medicine advanced. How is it that some persons develop many of the “chronic diseases of old age” and others do not? Now, with increasing understanding of the most basic cellular process in aging cells (e.g., oxidation) and advances in the genomic sciences, the line between aging and chronic conditions is blurred. We now know that most lung disease in late life can be avoided by not smoking earlier in life; yet as one ages one is more susceptible to pneumonia. A diagnosis of an HIV infection no longer means imminent death. With the introduction of antiretroviral therapy in the 1990s, persons are living longer than they ever had before. A large number of persons with stabilized and therefore chronic HIV are now in middle age and soon to be entering late life (see Chapter 21). The worldwide incidence of stroke has fallen as people are able to better control their blood pressure, exercise, and eat healthier, yet heart disease remains the primary cause of death for persons across the globe. Persons with new chronic conditions often continue to work and perform their usual routine. Later, and with increasing age, the effects of the limitations caused by the condition become noticeable (Figure 15-1). The person may receive assistance and rehabilitation in the home or in a designated rehabilitation center when the disabilities are first significant or during exacerbations in the limitations. As the limitations increase further, the person at home may move to the home of another and receive informal help or into an institutional setting where formal help is available. The most common chronic condition in persons over 65 is hypertension, followed by arthritis (Figure 15-2). Yet for the older adult, the presence or absence of a condition is not as important as its affect on function. The effect may be as little as an inconvenience or as great as an impairment of one’s ability to live independently (Figure 15-3). Working with those with chronic health conditions means that the gerontological nurse has the opportunity to decrease mortality of older adults and minimize the potentially disabling effects of chronic disease, that is, to be instrumental in decreasing morbidity. This chapter provides a snapshot of the most common chronic conditions the nurse will see in persons who depend on him or her for care and proposes strategies to promote healthy living regardless of the limitations with which one lives. We neither cover all possible conditions nor do we provide comprehensive medical management of these disorders. However, certain disorders are encountered frequently enough in late life to merit special attention. These include specific medical diagnoses and conditions in body systems. Other conditions such as those of the eyes and skin are addressed in Chapters 6 and 11. While there are many conceptual models from which chronic illness can be viewed, the trajectory model originally conceptualized by Anselm Strauss and Barney Glaser (1975) and later Corbin and Strauss (1992) has long aided health care providers to understand the realities of chronic illness and its effect on individuals. According to this theoretical approach, chronic illness can be viewed from a life course perspective or along a trajectory trace. In this way, the course of a person’s illness can be viewed as an integral part of their lives rather than an isolated event. The nurse’s response is then holistic rather than isolated. Woog (1992) divided Glaser and Strauss’ model into eight phases for the purpose of identifying goals and developing interventions. The trajectory may include a preventive phase (pretrajectory), a definitive phase (trajectory onset), a crisis phase, an acute phase, a stable phase, an unstable phase, a downward phase, and dying phase (Table 15-1). The shape and stability of the trajectory is influenced by the combined efforts, attitudes, and beliefs held by the elder, family members and significant others, and the involved health care providers. Key points of the model are based on the theoretical assumptions listed in Box 15-1. TABLE 15-1 THE CHRONIC ILLNESS TRAJECTORY 1. To assist a client in overcoming a plateau by increasing adherence to a regimen so that he or she might reach the highest level of functional ability possible within limits of the disability. 2. To assist a client in making the attitudinal and lifestyle changes that are needed to promote health and prevent disease. 3. To assist a client who is in a downward trajectory to be able to maintain sense of self and receive expert palliative care. 4. To assist with advance care planning to assure wishes are met. 5. To assist the client who is in an unstable phase to gain greater control over symptoms that are interfering with his or her ability to carry out everyday activities. See Woog P: The chronic illness trajectory framework: the Corbin and Strauss nursing model, New York, 1992, Springer. The person’s perceptions of both needs met and functional limitations are paramount to predicting movement along the illness trajectory (Corbin & Strauss, 1992). By using this approach, the gerontological nurse may have the biggest impact on promoting the health of the person with a chronic condition. In 2009 the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute reported that as of 2006 17.6 million persons in the United States had some form of cardiovascular disease (CVD). It is the leading cause of death for all persons over 65 and living in the United States with the exception of Asian Americans, for whom it is second (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [NHLBI], 2010). It is also the primary diagnosis of persons admitted to long-term care facilities and acute care hospitals (Auerhahn, et al., 2007). The high rate of CVD in later life is caused from a combination of genetics, normal changes with aging, risk factors such as smoking, and environmental factors such as pollution and stress, and in some cases, discrimination and racism (Box 15-2). Treatment approaches, mortality, and morbidity are highly variable by ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic group. Hypertension (HTN) is the most common chronic cardiovascular disease encountered by the gerontological nurse. Both the definition of and the guidelines for treatment of HTN are provided by the Joint National Committee of the Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC)*. According to JNC, HTN is diagnosed any time the diastolic blood pressure reading is 90 or higher or the systolic reading is 140 or higher on two separate occasions (JNC 7, 2003) (Table 15-2). However, the average of three readings is recommended for older adults due to age-related variability. Blood pressure, especially systolic blood pressure, increases with age, and an elevation of 140 mm Hg or more is a much more important risk indicator than a diastolic elevation in persons over age 50. Contrary to prior knowledge, it was found that the parameters for the diagnosis of HTN did not change with age (Box 15-3). The current blood pressure goal of all persons is less than 140/90 and equal to or less than 130/80 for persons with diabetes (JNC 7, 2003). The U.S. Prevention Task Force has recommend that persons with blood pressure readings of <120/80 be screened every two years and once a year for those with SBP of 120-139 or DBP 80-90 (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF], 2007a). TABLE 15-2 All persons with hypertension should be screened for diabetes. As of 2007, over 74 million Americans were thought to have HTN. The prevalence is highest among African Americans at all ages and lowest among Mexican Americans (NHLBI, 2010). Although the genetic predisposition cannot be controlled, many risk factors for both the disease and complications are modifiable (Box 15-4). Hypertension is a multigenic disease with strong familial clustering, however the effect of the environment and other endogenous factors are so significant that research is ongoing in an attempt to both understand and control the disease. Arterial stiffness and reduced vascular compliance, both normal changes with aging, are the factors most likely to account for the increased incidence of HTN among older adults. Decreased baroreceptor sensitivity may explain the variability of the blood pressure. Both changes in renal function and the neurohumoral system may explain the fact that approximately two thirds of older adults have sodium-sensitive hypertension, especially in the black population (Auerhahn, et al., 2007). Secondary causes are relatively rare in older adults and include pheochromocytoma, Cushing’s syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, thyroid/parathyroid disease, and chronic kidney disease (NHLBI, 2008). Both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions that promote a healthy lifestyle have been found to be effective in controlling HTN and minimizing the complications that can significantly interfere with quality of life. The universal use of thiazide-type diuretics (e.g. chlorothiazide) was recommended when the evidence was conclusive that this would improve both mortality and morbidity of persons with HTN. It is expected that in most cases more that one type of antihypertensive medications will be needed based on concurrent co-conditions, such as diabetes and race. Pharmacological guidelines, including adjustments by race, can be found in the JNC 7 report supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (www.nhlbi.nih.gov). By reducing or eliminating modifiable risk factors, hypertension can be controlled or prevented leading to healthier aging (Table 15-3). With few exceptions (e.g., late-stage dementia), maintaining blood pressure control is recommended regardless of the overall disease state. This means reducing the pulse pressure and keeping the blood pressure less than 140/90 mm Hg for otherwise healthy adults and less than 130/80 mm Hg for persons with diabetes. TABLE 15-3 BENEFITS OF CONTROLLING BLOOD PRESSURE TABLE 15-5 COMPARISON OF ARTERIAL AND VENOUS INSUFFICIENCY OF THE LOWER EXTREMITIES There is considerable evidence regarding the importance of diet. Healthy eating habits and weight loss have been found to irrefutably lower blood pressure (Table 15-4). Even modest reductions in sodium intake and weight may make a significant difference. A healthy diet includes control of cholesterol, sodium, and calories. It is now recommended that all persons limit their daily sodium intake to less than 2400 mg/day. Teaching people how to read food labels can be a first step. An evidence-based DASH diet is available from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute at www.nhlbi.nih.gov (see Chapter 14). When combined with the appropriate medications, the long-term complication of heart disease can be reduced (Box 15-5). TABLE 15-4 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFESTYLE CHANGE AND REDUCTION IN SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE SBP, Systolic blood pressure; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; ETOH, alcohol. While 425,000 deaths in 2006 were attributed to CHD, the death rate has declined dramatically in the past 20 years. While this rate has declined for persons of all races, it remains highest among African Americans and lowest among Asian Americans (NHLBI, 2010) (Figure 15-4). The incidence in men exceeds the incidence in women until after menopause, at which time the rate in women accelerates. It has been found that 70% of persons over age 70 had ≥50% atherosclerotic obstruction in at least one coronary artery on autopsy (Auerhahn, et al., 2007). Blockage may be from atherosclerosis, referred to as hardening of the arteries caused by the accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages within the arterial wall and the formation of plaques (Figure 15-5). The plaques reduce the capacity for oxygenation of the surrounding tissue. With complete obstruction, ischemic pain and tissue necrosis occur, and death may follow. With only partial blockage, the pain may be intermittent and experienced as angina. In severe cases of complete blockage, the result is acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and tissue necrosis. Risk factors for an AMI are both intrinsic and extrinsic and therefore somewhat modifiable (Figure 15-6). The pain of ischemic cardiac origin is classically described as a pressing or squeezing, usually in the chest under the breastbone, but sometimes in the shoulders, arms, neck, jaws, or back. While these are the classic signs and symptoms earlier in life (especially for men), this varies greatly with age and varies by gender. In later life, only 19% to 66% of persons complain of chest pain, 20% to 59% complain first of dyspnea, 15% to 33% have neurological manifestations, and up to 19% may have gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea and vomiting) associated with an AMI (Auerhahn, et al., 2007). This array of non-specific and atypical symptoms often leads to misdiagnosis, which delays the prompt medical intervention needed for optimal outcomes. Both non-invasive (e.g., ECG, stress test) and invasive (e.g., coronary angiography, thallium perfusion scintigraphy) tests may be necessary to make a definitive diagnosis of CAD or estimate the extent of damage. A definitive diagnosis of an AMI (MI) requires the documentation of changes in biochemical markers within 24 to 72 hours of the event (see Chapter 8). In late life, many, but not all, diagnoses of CAD and cardiac events are made at the time of a screening electrocardiogram (ECG). However, because of the high numbers of false-negative ECGs, delayed recognition leads to increases in the rate of complications. Heart failure (HF) is a general term used to describe the end result of the combination of normal changes with aging and other cardiac disorders. As more persons live longer with heart disease, more failure is seen in both men and women, affecting about five million persons in the United States. Seventy-five percent of the 500,000 new cases each year occur to persons over 65 (Bashore et al., 2010). It is the most common cause for hospitalization, re-hospitalization, and disability among persons over age 65 (Figure 15-7). Clinical heart failure is categorized as systolic failure, diastolic failure, or both. End-stage and acute heart failure is known as congestive heart failure (CHF) and is quite common (Auerhahn et al., 2007). In contrast, right-sided heart failure is associated with LV systolic dysfunction; the ejection fraction is ≤50%, and the person is symptomatic and may be very ill. Long-standing left-sided failure will eventually cause right-sided failure as well. While the overall prevalence of CHF in African Americans is higher than in whites, persons from the latter group have a 30% to 50% higher rate of hospitalization (Jones-Burton & Saunders, 2006). Diagnosis is often made empirically, that is, based on presenting symptoms and examination. A definitive diagnosis requires the finding of enlargement of the heart’s chambers, especially the ventricles. A determination of ejection fraction (per ECG) is then essential in the determination of the appropriate pharmacological management and advance planning. A serum BNP is useful in differentiating dyspnea due to heart failure with that caused by other conditions. Both the BNP and the N-terminal pro-BNP are excellent biomarkers with similar accuracy (see Chapter 8) (Bashore, et al., 2010).

Chronic Conditions

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Theoretical Frameworks for Chronic Disease

Chronic Illness Trajectory

PHASE

DEFINITION

1. Pre-trajectory

Before the illness course begins, the preventive phase, no signs or symptoms present

2. Trajectory onset

Signs and symptoms are present, includes diagnostic period

3. Crisis

Life-threatening situation; acute threat to self-identity

4. Acute

Active illness or complications that require hospitalization for management

5. Stable

Controlled illness course/symptoms

6. Unstable

Illness course/symptoms not controlled by regimen but not requiring or desiring hospitalization

7. Downward

Progressive decline in physical/mental status characterized by increasing disability/symptoms

8. Dying

Immediate weeks, days, hours preceding death

Examples of goals that nurses might establish include the following:

Cardiovascular Disease

Hypertension

CLASSIFICATION

BLOOD PRESSURE

Normal

<120 systolic and <80 diastolic

Prehypertension

120-139 systolic or 80-89 diastolic

Stage 1 HTN

140-159 systolic or 90-99 diastolic

Stage 2 HTN

>160 systolic or >100 diastolic

Etiology

Promoting Healthy Aging; Implications for Gerontological Nursing: Hypertension

AVERAGE PERCENT REDUCTION IN RISK FOR NEW EVENTS

Stroke decreased

30%-40%

Myocardial infarction decreased

20%-25%

Heart failure decreased

50%

CHARACTERISTICS

ARTERIAL

VENOUS

Pain

Pulses

Associated changes in leg and foot

Ulcer location

Ulcer characteristics

LIFESTYLE CHANGE

APPROXIMATE REDUCTION IN SBP

Weight reduction

Decrease of 5-20 mm Hg per 10-lb loss

Adopt the DASH diet

Decrease of 8-14 mm Hg

Lower sodium intake

Decrease of 2-8 mm Hg

Increase physical activity

Decrease of 4-9 mm Hg

ETOH in moderation

Decrease of 2-4 mm Hg

Coronary Heart Disease

Etiology

Signs and Symptoms

Promoting Healthy Aging; Implications for Gerontological Nursing: Coronary Artery Disease

Heart Failure

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chronic Conditions

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access