CHAPTER 28 1. Identify the nature and scope of family violence and factors contributing to its occurrence. 2. Identify three indicators of (a) physical abuse, (b) sexual abuse, (c) neglect, and (d) emotional abuse. 3. Describe risk factors for both victimization and perpetration of family violence. 4. Describe four areas to assess when interviewing a person who has experienced abuse. 5. Identify two common emotional responses the nurse might experience when faced with a person subjected to abuse. 6. Formulate four nursing diagnoses for the survivor of abuse, and list supporting data from the assessment. 7. Write out a safety plan for a victim of intimate partner abuse. 8. Discuss the legal and ethical responsibilities of nurses when working with families experiencing violence. 9. Compare and contrast primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of intervention, giving two examples of intervention for each level. 10. Describe at least three possible referrals for an abusive family, including the telephone numbers of appropriate agencies in the community. 11. Discuss three psychotherapeutic modalities useful in working with abusive families. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis The American Academy of Family Physicians defines family violence as the “intentional intimidation, abuse, or neglect of children, adults, or elders by a family member, intimate partner, or caretaker in order to gain power and control over the victim” (2008, para. 1). Legal definitions of family or domestic violence vary from state to state; 46 states have specific definitions in their civil statutes (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2011). Specific types of abuse have been identified as physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, and economic abuse. Physical abuse is the infliction of physical pain or bodily harm (e.g., slapping, punching, hitting, choking, pushing, restraining, biting, throwing, and burning). Sexual abuse is any form of sexual contact or exposure without consent, or in circumstances in which the victim is incapable of giving consent. Sexual abuse is also referred to as sexual assault or rape and is discussed in Chapter 29. Emotional abuse is the infliction of mental anguish (e.g., threatening, humiliating, intimidating, and isolating). Neglect is the failure to provide for physical, emotional, educational, and medical needs. Economic abuse is controlling a person’s access to economic resources. Each of these types of abuse will be addressed in more depth in this chapter. In 2010 there were 3.3 million referrals for child abuse, 20% of which were substantiated (USDHHS, 2011). The most common form of abuse was neglect (78%), followed by physical abuse (17%), sexual abuse (9%), and emotional abuse (8%). Table 28-1 gives statistics related to abuse rates and fatalities among different ethnicities. TABLE 28-1 VICTIMS OF ABUSE AND FATALITIES AMONG DIFFERENT ETHNICITIES: 2010 Data from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2011). Child maltreatment 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Girls are slightly more likely to be abused, comprising 51% of victims. In general, the younger the child the more vulnerable she or he is to abuse. Tragically, children under the age of 1 account for about 21% of all abuse cases (USDHHS, 2011). Approximately 80% of children who die are younger than 4 years of age, and boys die at a slightly higher rate than girls. The abuse of neglect is the most common cause of death. The prevalence of sexual abuse in children is difficult to determine due to the fact that children are often unable to describe their experience. Relatively uncommon in infants, sexual abuse increases with age. Beginning at puberty, the rate of sexual abuse is about 9% of all abuse cases (USDHHS, 2011). It is estimated that 80% of perpetrators are the victim’s parents (USDHHS, 2011). Mothers abuse more frequently and account for 37% of cases, fathers acting alone account for 19% of abuse cases, both parents as abusers occurs in 18% of cases, and in 7% of the cases the abusers are a parent along with another person. According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (Black et al., 2011), more than 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have experienced physical violence, rape, and/or stalking by an intimate partner at some time in their lives. Females are victimized about 6 times more often than males. In persons aged 12 and older, about 4 females per 1000 persons report abuse while males report abuse at a rate of 0.8 per 1000 persons (U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007). The gender gap of physical violence in intimate partner relationships seems to be narrower. Nearly 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have been slapped, pushed, or shoved by an intimate partner in their lifetimes (Black et al., 2011). Nearly half of married couples have instances of abuse, and evidence suggests that intimate partner violence affects same-sex relationships at about the same rates as heterosexual relationships (Stephenson et al., 2011). One out of 10 homicides is due to spousal murder, and about a third of females who are killed are or were in an intimate relationship with their killer. According to the American Psychological Association (APA) (2012), every year about 2 million older adults in the United States are reported to be physically abused, psychologically abused, or neglected. The APA suggests that the number may be far higher and that for every case reported, five go unreported. Further complicating the picture is that the older adult may be caring for himself or herself, which creates the potential for self-neglect. Elder abuse occurs in both institutional and family settings. Family members are reported to be the perpetrators in about 76% of incidents (Acierno et al., 2010). Abused adolescents exhibit more psychopathological changes, poorer coping and social skills, a higher incidence of dissociative identity disorder, and poorer impulse control than do other adolescents. Women who are victims of prolonged childhood sexual abuse are more likely to develop major psychiatric distress. Box 28-1 identifies some of the long-term effects of family violence. The occurrence of abuse requires the following participants and conditions: 2. Someone who by age or situation is vulnerable (children, women, older adults, and mentally ill or physically challenged persons) The propensity for violence is rooted in childhood and manifested by a general lack of self-regard, dissatisfaction with life, and inability to assume adult roles. Often the abuser lacked good role models and was deprived of the opportunity to develop problem-solving skills. Witnessing or experiencing family violence, neglect, or abusive parenting (Box 28-2) are contributing factors. Perpetrators, those who initiate violence, often consider their own needs to be more important than anyone else’s and look toward others to meet their needs. Walker (1979) describes a pattern of behavior that perpetrators of violence may use to control their partners. While there is little empirical evidence testing Walker’s theory, it is commonly cited to describe the dynamics of an abuser’s behavior. The tension-building stage is characterized by relatively minor incidents, such as pushing, shoving, and verbal abuse. During this time, the victim often ignores or accepts the abuse for fear that more severe abuse will follow. Abusers then rationalize that their abusive behavior is acceptable. As the tension escalates, both participants may try to reduce it. The abuser may try to reduce the tension with the use of alcohol or drugs, and the victim may try to reduce the tension by minimizing the importance of the incidents (“I should have had the house neater …. dinner ready”). Unfortunately, without intervention, the cycle will repeat itself. Over time, the periods of calmness and safety become briefer, and the periods of anger and fear are more intense. There are intervals of stability, but the violence increases over time. With each repeat of the pattern, the victim’s self-esteem becomes more and more eroded. The victim either believes the violence was deserved or accepts the blame for it. This can lead to feelings of depression, hopelessness, immobilization, and self-deprecation. Figure 28-1 illustrates the cycle of violence. Minority groups, particularly those experiencing poverty and social marginalization, may have the label of perpetrator or abuser applied to them more often than those who are more socioeconomically advantaged (Malley-Morrison & Hines, 2004). It is important to recognize that a wide variety of cultural norms dictate relationships among intimate partners and child-rearing practices. Learning about the cultural backgrounds of patients can prevent mistaking common cultural norms for abuse. Victims of violence are encountered in every health care setting; therefore, all patients should be screened for possible abuse. Due to the number of victims of violence seen in emergency departments, the Emergency Nurses Association (2006) issued a formal position statement urging nurses in this specialty area to be active in promoting hospital and community teams to treat and protect people from domestic violence, abuse, and neglect. Important and relevant information about the family situation can be gathered by routine assessment conducted with tact, understanding, and a calm, relaxed attitude. A person who feels judged or accused of wrongdoing is likely to become defensive and may not be receptive to changing behavior. It is better to ask about ways of solving disagreements or methods of disciplining children rather than to use the words abuse or violence. It is also important not to assume a person’s sexual orientation; rather, use the term partner when asking about the relationship. Key interviewing guidelines are listed in Box 28-3. • Tell me about what happened to you. • Who takes care of you? (for children and dependent older adults) • What happens when you do something wrong? (for children) or How do you and your partner/caregiver resolve disagreements? (for women and dependent older adults) • Who helps you with your child(ren)/parent? Questions that are open-ended and require a descriptive response can be less threatening and elicit more relevant information than questions that are direct or can be answered with yes or no (refer to Chapter 9): • What arrangements do you make when you have to leave your child alone? • How do you discipline your child? • When your infant cries for a long time, how do you get him/her to stop? When trust has been established, openness and directness about the situation can strengthen the relationship with those experiencing or perpetrating violence. A five-question assessment tool developed by Soeken and colleagues (1998) has been used extensively to assist in the routine identification of intimate partner abuse (Figure 28-2). A series of minor complaints, such as headaches, back trouble, dizziness, and accidents (especially falls), may be a covert indicator of violence. Overt signs of battering include bruises, scars, burns, and other wounds in various stages of healing, particularly around the head, face, chest, arms, abdomen, back, buttocks, and genitalia. Injuries that should arouse the nurse’s suspicion are listed in Box 28-4.

Child, older adult, and intimate partner violence

Clinical picture

Types of abuse

Epidemiology

Child abuse

RACE OR ETHNICITY

% OF TOTAL ABUSE CASES

% OF TOTAL CHILD FATALITIES

African American

21.9%

28.1%

American Indian or Alaska Native

1.1%

0.8%

Children of multiple races

3.5%

4.4 %

Hispanic

21.4%

16.6%

White

44.8%

43.6%

Asian

0.9%

0.9%

Intimate partner abuse

Older adult abuse

Comorbidity

Etiology

Environmental factors

Perpetrator

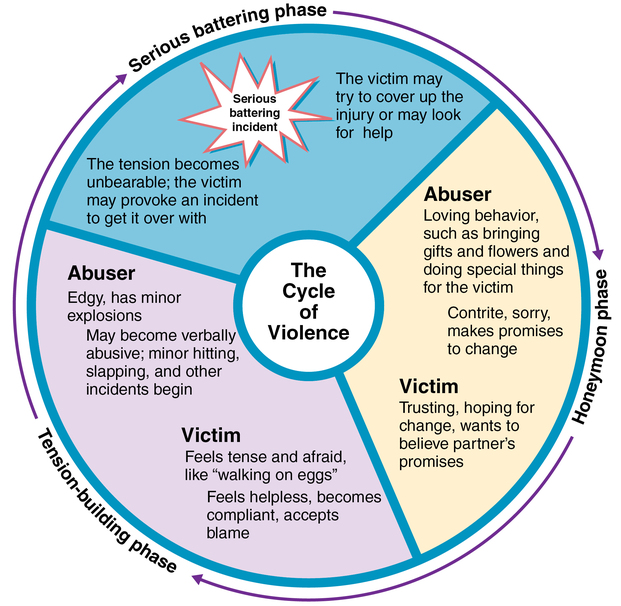

Cycle of violence.

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

General assessment

Interview process and setting

Types of abuse

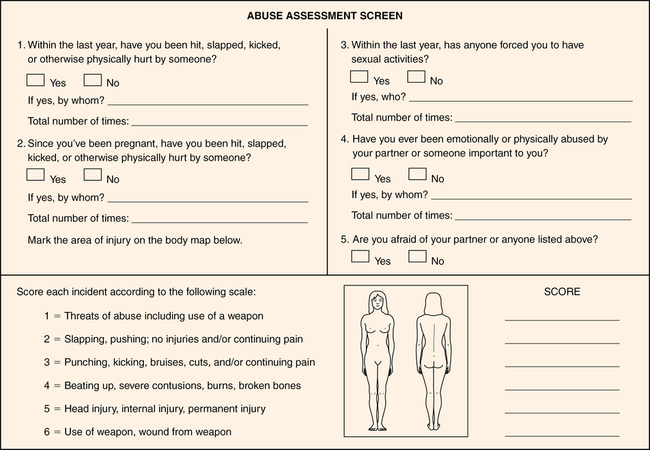

Physical abuse

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree