Child and Adolescent Health

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

3. Discuss the built environment and how it relates to major health issues of children and adolescents.

Key Terms

abusive head trauma, p. 661

body mass index, p. 656

built environment, p. 654

child feeding practices, p. 656

child maltreatment, p. 661

Children’s Health Insurance Plan, p. 649

cognitive development, p. 651

development, p. 651

developmental screening, p. 652

environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), p. 667

family-centered medical home, p. 668

food deserts, p. 655

food landscape, p. 655

growth, p. 651

H1N1, p. 663

human ecology theory, p. 652

immunization, p. 653

interactive health communication (IHC), p. 668

low food security, p. 649

media, p. 658

Medicaid, p. 649

medical home, p. 668

motivational interviewing, p. 668

obesity, p. 654

overweight, p. 654

psychosocial development, p. 651

sudden infant death syndrome, p. 663

unintentional injuries, p. 659

—See Glossary for definitions

Cynthia Rubenstein, RN, PhDc, CPNP-PC

Cynthia Rubenstein, RN, PhDc, CPNP-PC

Cynthia Rubenstein is currently a faculty member at James Madison University in the Department of Nursing. She has over 18 years of experience in pediatric nursing, from NICU to ER to home health, and she has been a practicing pediatric nurse practitioner for 13 years. She is active in developing childhood obesity prevention educational programs. Dr. Rubenstein works collaboratively with a multidisciplinary team to develop expert nutritional content for an interactive Web-based educational program for the Virginia WIC program.

Walt Disney identified the greatest natural resource of any nation as the minds of its children. The future of the world depends on how well it cares for its youth. If this population is to thrive, it must be nurtured in an appropriate environment. Focusing on the health needs and health promotion of children increases the chances that they will become adults who value and practice healthy lifestyles. Population-focused nurses have two major roles in the area of child and adolescent health:

The population-focused nurse has the opportunity to teach healthy lifestyles to children and caregivers and to provide family-centered care in the community setting. This chapter provides information on the assessment of children and adolescents as well as activities to promote their health. The content includes basic principles of childhood growth and development and major health problems seen in this population. The concept of evaluating child health and implementing health education and models of health behavioral change will be explored within the context of the child’s built environment. The family-centered medical home, motivational interviewing, and the use of interactive health communication are discussed in this chapter as strategies to promote improved health behaviors within families. Healthy People 2020 objectives (USDHHS, 2010) are used as a framework for focusing on needs of children in the community.

Status of Children

Poverty Status

There were 73.9 million children through age 17 in the United States in 2008, representing slightly more than 25% of the population (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2008a; USCB, 2009b). Approximately 40% of them live in low-income families, with one out of every five children living below poverty levels and 8% of America’s children living in extreme poverty with a family income of half of the federal poverty level. The federal poverty level for 2009 was defined as a family income of less than $22,050 for a family of four whereas low income (the amount of income necessary to provide for the family’s basic needs) is two times the federal poverty level.

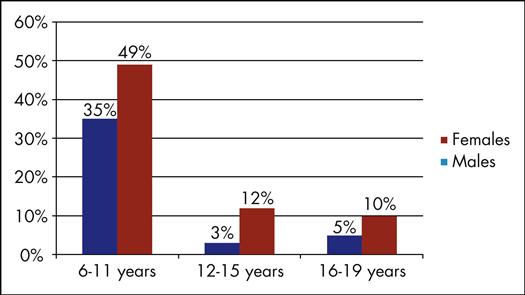

Minority children, most notably black and Hispanic children, have higher proportions of living at poverty or low-income levels (Figure 29-1). About 60% of children born to immigrant parents live in low-income families compared with 37% of native-born parents (Wight and Chau, 2009). Characteristics that put children at risk for living in low-income families are parents without a high school degree, having a lack of parental employment, and living in a single-parent household. Children’s ability to learn in school and reach their full cognitive ability is affected by low-income status. Children living in poverty experience a higher incidence of behavioral, social, and emotional problems (Wight, Chau, and Aratani, 2010).

In addition, U.S. children face other challenges. More than 20% of American households with children experience low food security. Low food security, a lack of available food and access to food on a regular basis, affects children’s physical health, development, and school performance. Homelessness is increasing for American children and is highly correlated to poverty status (Wight and Chau, 2009; Wight, Chau and Aratani, 2010). It is estimated that over 10 million children each year are witnesses to or victims of violence, and this exposure to violence is linked to physical, emotional, and behavioral problems.

Access to Care

Access to quality health services is one of the focus areas of Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2010). Children with health care coverage are more likely to have a regular and accessible source of health care. In 2007, 11% (8.1 million) of all children had no health insurance. For children living in poverty, in 2007 the uninsured rate for children was 17.6% (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, Smith, 2008). The number of children covered by government health insurance programs has been climbing since then.

The Medicaid program, established by the Social Security Act in 1965, is a state-administered health insurance program financed jointly by the federal and state governments. Children under 18 years of age living in a household with an income level at or below 133% of the federal poverty level or children meeting disability requirements qualify for this program. The program provides health services at no cost to participants and includes outpatient visits, hospitalization, laboratory testing, immunizations, well care/preventive services, and dental care (CMMS, 2010). In June 2009, 24.8 million children under the age of 18 years were enrolled in the Medicaid program, which is a 12.1% increase from the previous year (KFF, 2010).

The Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP) was the result of federally mandated legislature passed in 1997 to expand health insurance to the nation’s uninsured children. The Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 has continued to provide insurance to over 5 million American children. CHIP is a federal and state partnership that is directed toward uninsured children and pregnant women in families with incomes too high to qualify for state Medicaid programs but usually too low to afford private coverage. Following federal guidelines, each state determines the model of its particular CHIP program, which includes the eligibility parameters, benefit package, payment levels for coverage, and administrative process. The program is jointly financed by the federal and state governments, and administered by the states (CMMS, 2009) (Box 29-1).

CHIP enrollment has steadily increased annually since its inception, and 7.3 million children were enrolled in the program in 2008. The lowest enrolling eligible groups are Hispanic and non-English-speaking families (Division of State Children’s Health Insurance, 2008). Over 5 million children remain who likely qualify for CHIP but are without health insurance (USCB, 2009a). This is an area of outreach opportunity for nurses to identify potential families eligible for CHIP and provide appropriate referrals to state agencies.

With the passage of federal health care reform in 2010 (HR 3590), changes to both the Medicaid and CHIP programs will be forthcoming with the beginning of states’ health insurance exchanges. The full impact will not be noted until complete implementation of health care reform occurs later in the decade. With the anticipated health insurance coverage of all children, health outcomes and preventive services for children in the United States should improve dramatically.

Infant Mortality

Promotion of healthy pregnancies is a focus of Healthy People 2020. The Healthy People 2020 target goal for the U.S. infant mortality rate is 4.5 infant deaths per 1000 live births. The U.S. infant mortality rate steadily declined over the past decades and is currently 6.2 per 1000 live births. Although infant death rates have decreased, the United States has a higher infant mortality rate than 44 other nations (CIA, 2009) and its position in a global ranking has consistently fallen over past years.

Infant mortality rates are critical indicators of a country’s overall health. Infant mortality rates are associated with a variety of factors such as maternal health, socioeconomic circumstances, quality and access to medical care, and community health practices. The infant mortality rate for specific ethnic groups in the United States is significantly higher for non-Hispanic black (13.63 per 1000 live births), Puerto Rican (8.30 per 1000 live births), and American Indian or Alaska Native (8.06 per 1000 live births) (MacDorman and Mathews, 2008).

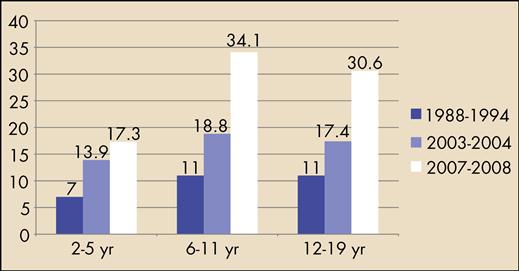

Risk-Taking Behaviors

Risk behaviors are any behaviors that place early and middle adolescents at risk for physical, emotional, or psychological harm. Much progress has been made through health promotion and education to decrease risk factors in adolescents. There have been consistent declines in the number of teens who smoked tobacco (20%), used marijuana (17.9%), and rode in the car with a driver who drank alcohol (29.1%). Increasingly, drugs of abuse are inhalants. Nationally, 13.3% of high school students have breathed the contents of aerosol spray cans, sniffed glue, or inhaled any paints or sprays to get high one or more times (NCDPHP, 2010).

There are still unchanged rates of adolescents engaging in sexual activity (47.8%), using condoms during intercourse (61.5%), and currently using alcohol (44.7%) (NCDPHP, 2010). From the 1990s through 2005, adolescent birth rates dropped steadily to approximately 42 per 1000 15- to 19-year-old adolescents. This number remains a significant concern for public health nurses since teen pregnancy has a significant socioeconomic burden on society and the family (CDC, 2010b).

Nurses should be aware of the factors associated with increased adolescent risk-taking behaviors: poor academic performance, poor parental role models, low self esteem, lack of a supportive social environment, and poverty. Individual assessment of an adolescent’s risk-taking behavior can provide the direction to focus education and interventions. Providing afterschool extracurricular activities, identifying a positive adult role model, and engaging teens in support systems to build self-esteem can reduce risk-taking behaviors in at-risk adolescents.

A recent concern has emerged about the misuse and abuse of prescription stimulant medication to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Misuse of these drugs occurs in 5% to 9% of children and adolescents. Misuse ranges from selling or trading the prescription stimulant, taking a prescription stimulant with no ADHD symptoms, taking more than the recommended dose, or taking it by a route other than the prescribed route (i.e., inhaling an oral medication) (Wilens et al, 2008). It is vital to promote community and family awareness of this problem and educate children and adolescents on the dangers of taking others’ prescription medications.

Child Development

Growth and Development

Growth is the measurable aspect of the individual’s size and follows a predictable pace that is evaluated at regular intervals to determine if a child is growing based on standard parameters. Development involves the observable changes in the individual and relates to physical, psychosocial, and cognitive achievements. Growth and development in children is an ongoing, dynamic process that results in physical, cognitive, and emotional changes (Figure 29-2). Health visits or well-child check-ups are scheduled at key ages to monitor these processes and provide anticipatory guidance to families. Nursing assessments include growth and health status, developmental level, and the quality of the parent–child relationship. (See Tables 29-2, 29-3, 29-4, and 29-5 for considerations and issues to address at each stage.) The recommendations for preventive pediatric health care (see Resource Tool 5.A on the Evolve site) list components of well-child assessments. Further tools and specific interventions are included in Appendixes D and E.

Developmental Theories

Many developmental theories provide perspectives on children’s growth and development. The work of Erik Erikson on psychosocial development emphasizes that personality development culminates in the achievement of ego identity, which involves accepting oneself and having the skills for healthy functioning in society (Figure 29-3). According to Erickson, development is a continual process that occurs in distinct stages with a developmental crisis needing resolution at each stage and some degree of mastery being achieved before proceeding successfully to the next stage. All new development is rooted in prior experiences, and difficulty resolving the crisis will cause problems progressing through the subsequent stages.

The work of Jean Piaget is widely used to understand the process of cognitive development. According to Piaget, learning results from actively manipulating objects and information, which is followed by a mental processing of the event. As the child interacts with the environment, new objects and problems are discovered. The child creates mental schemes or thought patterns to understand the encounter. This permits the child to receive information from the world, make sense of it, and predict future events. Development occurs as the schemes increase in scope and complexity. Piaget identified four stages of cognitive development that represent increasing problem-solving ability. As one will remember from pediatric courses, these stages are sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete and formal operations.

Bronfenbrenner’s human ecology theory emphasizes the complex relationship between the growing child and his/her immediate environment. Children are greatly influenced by the environments in which they spend time and one of the most important environments in affecting growth is the family environment. Educational programs, communities, and other environmental factors also influence the child’s development. Children learn to accommodate to their environment and alter themselves based on environmental interactions. This theory explains that individuals do not develop in isolation but in relation to their home and family, school, community, and society.

Developmental Screening

Developmental screening is a process designed to identify children who should receive more intensive assessment or diagnosis of potential developmental delays. These delays may be in any of the developmental domains—gross motor, fine motor, language, or social skills. Developmental screening promotes early detection of delays and improves child health and well-being for identified children. In the United States, 17% of children have a developmental disability such as autism, attention-deficit disorder, or a language delay; yet only 50% of these children were diagnosed prior to school entry. Nurses are critical to early screening and identification of developmental delays in young children and appropriately initiating referrals to maximize school readiness and maximum achievement. Multiple screening tools are available and are selected based on the nurse’s role in the community (Table 29-1).

TABLE 29-1

| TOOL | PURPOSE |

| Denver II | Domain specific development (gross and fine motor, social, language) |

| Ages and Stages Questionnaire | Social and emotional development |

| Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) | General developmental and behavioral screening |

| Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) | Autism spectrum disorder |

| Pediatric Symptom Checklist | Coping and mental health concerns |

Children with delayed skills or other disabilities may qualify for special services that provide individualized education programs in public schools that are free of charge to families. Nurses can be effective health advocates for these children within educational settings. The passage of the updated version of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004) promotes a collaborative focus on meeting the needs of children with disabilities. Parents, educators, administrators, nurses, and other team members collaboratively develop a plan—the individualized education plan (IEP)—to help children succeed in school. The IEP explains the goals the team sets for a child during the school year as well as any special support needed to help achieve these goals.

Immunizations

Increasing immunization coverage for children remains a significant focus of the Healthy People 2020 objectives. Currently, 93% of the nation’s 19- to 35-month-old children have received all of the polio and hepatitis B vaccinations in the recommended series but only 44% have received the complete hepatitis A series (CDC, 2010c). For adolescents, although rates continue to rise steadily, vaccination rates remain low overall for this age group. For those aged 13 to 17 years, 40% received the recommended tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV4). Lowest immunization rates are noted for the human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) series, with 37% of girls receiving one dose and only 18% receiving the full three-dose series (CDC, 2009d). Routine immunization of children is very successful in the prevention of selected diseases. The ultimate challenge is making sure that children receive immunizations (Figure 29-4).

Barriers

There are several barriers to successful immunizations. These include vaccine cost, vaccine refusal by parents, vaccine shortages, and changes in vaccine scheduling and recommendations. Health disparities in vaccinations continue to exist. Children living in poverty have lower immunization rates than their peers, and African-American adolescents have lower immunization rates compared with white adolescents (Burns, Walsh, and Popovich, 2010). It is important to educate parents to obtain immunizations for their children and to focus on the issue at every encounter with families.

Parental fears about vaccines prevent children from getting immunized. Parents readily access the Internet for information about vaccines, and disreputable sites provide parents with incorrect vaccine information. It is critical for nurses to educate families on the safety and efficacy of vaccinations. Scientific studies have not found a relationship between immunizations and autism, sudden infant death syndrome, diabetes, neurological disabilities, deafness, or cancer. Parents question the need to vaccinate because the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases is low. However, Japan, Great Britain, and Sweden stopped the use of the pertussis vaccine, and within 5 years there were epidemic levels of the disease and rising death rates (CDC, 2007b). When a parent chooses not to vaccinate their child, this puts the child and others at risk.

Shortages of vaccines have periodically occurred as a result of manufacturing problems, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) has focused on maintaining adequate manufactured supplies of vaccines. When a shortage does occur, the CDC provides priority administration guidelines for highest-risk clients. When the immunization schedule is revised, there can be delays in practitioners implementing the new recommended vaccination schedules. Nurses will want to continually review the CDC recommendations for any changes to implement within the public health and community settings.

Vaccines and vaccine administration costs are high and those families without health insurance often find following the vaccination recommendations financially prohibitive. A federal program established in 1995, Vaccines for Children (VFC), provides free vaccines to eligible children, including those without health insurance coverage, children enrolled in Medicaid, American Indians and Alaskan Natives, and children whose health insurance does not cover vaccines. Identifying children who qualify for VFC is a primary prevention strategy of population-focused nurses.

Immunization Theory

The goal of immunization is to protect by using immunizing agents to stimulate antibody formation (see Chapter 13 for types of immunity). Immunizing agents for active immunity are in the form of toxoids and vaccines. A toxoid is a bacterial toxin (e.g., from the bacteria that cause tetanus and diphtheria) that has been heated or chemically treated to decrease virulence but not antibody-producing ability. Vaccines are suspensions of attenuated (live) or inactivated (killed) microorganisms. Examples include pertussis (inactivated bacteria); measles, mumps, and rubella (live attenuated viruses); and hepatitis B (inactivated virus).

The neonate receives placental transfer of maternal antibodies. This natural passive immunity lasts for about 2 months. Protection is temporary and is only to diseases to which the mother has adequate antibodies. The immune system of both term and preterm infants is capable of adequate antibody response to immunizations by 2 months of age. Generally, this is the recommended age to start immunizations; the exception is the hepatitis B series, which begins at birth.

The interval between immunizations is important to the immune response. After the first injection, antibodies are produced slowly and in small concentrations (the primary response). When subsequent injections of the same antigen are given, the body recognizes the antigen and antibodies are produced much faster and in higher concentration (the secondary response). Because of this secondary response, once an initial immunization series has been started, it does not need to be restarted if interrupted, regardless of the length of time elapsed. Once the initial series is completed, boosters are required at appropriate intervals to maintain an adequate concentration of antibodies. Further information about immunizing agents is available on the Evolve website.

Recommendations

Immunization recommendations rapidly change as new information and products are available. Two major organizations are responsible for guidelines: the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, 2009a) and the U.S. Public Health Service’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Current recommendations for children and adolescents can be found on the Evolve website. The main goal of the guidelines is to provide flexibility to ensure that the largest number of children will be immunized. All health care providers are urged to assess immunization status at every encounter with children and to update immunizations whenever possible.

Contraindications

There are relatively few contraindications to giving immunizations. Minor acute illness is not a contraindication. Immunizations should be deferred with moderate or acute febrile illnesses because the reactions may mask the symptoms of the illness. The side effects of the immunization may be accentuated by the illness.

People with the following conditions are not routinely immunized and require medical consultation: pregnancy, generalized malignancy, immunosuppressive therapy or immunodeficiency disease, sensitivity to components of the agent, or recent administration of immune serum globulin, plasma, or blood.

Legislation

The National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act became effective in 1988. It requires providers to counsel parents and clients about the risks and benefits of the immunizing agent as well as possible side effects. Informed consent is recommended. Vaccine information statements (VISs) are used for this purpose. The VISs are information sheets produced by the CDC that explain both the benefits and risks of a vaccine. Federal law requires that a VIS be given to parents or legal guardians before each vaccine dose is given.

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) is a national safety surveillance program. It requires providers and vaccine manufacturers to report any adverse effects following the administration of routinely recommended vaccinations. The program has been effective in tracking and identifying adverse effects associated with vaccinations. In 1999, VAERS detected reports of intussusception above what would be expected to occur by chance alone after the administration of the RotaShield rotavirus vaccine. Subsequently, this vaccine was pulled from manufacturing and the vaccine formulation was redeveloped.

The Built Environment

A built environment is simply defined as the person’s human-made or modified surroundings in which they live, work, and partake in recreation (Renalds, Smith, and Hale, 2010). This is the actual physical environment in which children live and includes neighborhood access to recreation opportunities, grocery stores, the home environment, and the consideration of general safety for children in their physical environments. A child’s built environment is influential in the managing of risk factors for obesity, amount and type of physical activity, risk for injuries, and exposure to environmental toxins. Therefore, as nurses, assessing a child’s built environment provides a foundation for identifying interventions and education to promote health and prevent injuries and diseases.

Obesity

Obesity rates in American children have risen to epidemic levels over the past few decades. These increases are noted for all children aged 2 to 18 years regardless of gender or ethnicity. The CDC defines overweight as a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 85th percentile and lower than the 95th percentile, and obesity is defined as a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for children of the same age and sex when plotted on the CDC growth charts (Table 29-2) (CDC, 2010d).

TABLE 29-2

| PLOTTED PERCENTILE FOR AGE AND GENDER | BMI INTERPRETATION |

| <5th percentile | Underweight |

| 5th-85th percentile | Normal |

| 85th-95th percentile | Overweight |

| >95th percentile | Obese |

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Classification of body mass index, 2009. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/

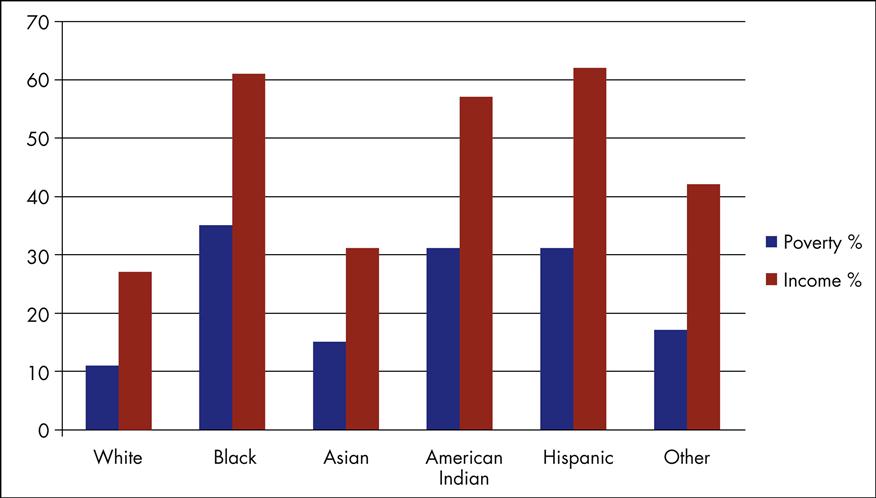

The prevalence of the overweight and the obese combined is 38% in children ages 2 to 5 years, 69% for children ages 6 to 11 years, and 65% for adolescents 12 to 19 years. The prevalence of obesity in children is approximately 17% for ages 2 to 5 years, 34% for ages 6 to 11 years, and 31% for ages 12 to 19 years (Ogden et al, 2010) (Figure 29-5). Comparing these 2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) findings with 1974 NHANES results demonstrates that prevalence rates for obesity have more than quadrupled for most children over the past 30 years (Ogden et al, 2002, Ogden et al, 2010).

The physiological consequences of childhood obesity are extensive and significantly impact the health status of American children. Research has clearly identified strong relationships between being obese as a child and increased disease risk and disease burden in the cardiovascular, metabolic, musculoskeletal, respiratory, and renal systems (Freedman et al, 2001; Viner et al, 2005; Miller et al, 2006;). Another critical consequence for children is the negative psychological and social impact of obesity with decreased self-esteem; higher incidence of depression, sadness, and anxiety; problems with social relationships; and higher reports of being the victim of bullying (Cornette, 2008; Gable, Britt-Rankin, and Krull, 2008; Wang et al, 2009).

Multiple factors contribute to the likelihood that a child will become overweight or obese. Genetics is certainly a contributing component, although the genetic composition of the population has been stable over time, thereby failing to account for a sudden rise in obesity in recent years (Lawrence and Chowdhury, 2004). Within the literature, three modifiable risk factors for the development of childhood obesity have been identified. These risk factors are monitor viewing hours (including television, computer, and video game monitors), physical activity engagement, and dietary intake/eating behaviors (AAP, 2003; Bowman et al, 2004; Kranz, Siega-Riz, and Herring, 2004; Taveras et al, 2007).

A rising co-morbidity for childhood obesity is type 2 diabetes mellitus. Currently, about 151,000 U.S. children and adolescents have type 2 diabetes. Children and adolescents diagnosed with type 2 diabetes are usually between 10 and 19 years old, are obese with a strong family history for type 2 diabetes, and have insulin resistance. Most children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes have poor glycemic control with hemoglobin A1C levels between 10% and 12%. Type 2 diabetes affects all ethnic groups but occurs more frequently in non-white groups (Nader and Kumar, 2008).

Screening for type 2 diabetes is recommended for children with a BMI of 85th to 95th percentile with two risk factors of family history of diabetes, belonging to a racial minority group, or with signs of insulin resistance; all children with a BMI above the 95th percentile; and at age 10 years or onset of puberty (ADA, 2000). In addition, these children should be screened for hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, which are also associated with childhood obesity. Nurses can be instrumental in the management of type 2 diabetes in children by educating and counseling families on lifestyle changes related to dietary habits and physical activity.

Built Food Environments

A discussion on the risk factors for childhood obesity should be considered within the context of a child’s environment. The emerging research on the relationship of built environments and obesity evaluates the factors within an individual’s environment that may contribute on a macro- or micro-level to the development of obesity. The current literature focuses on the role of the built environment in increasing energy consumption while decreasing energy expenditure and looks at the interaction of the individual with his or her environment that influences health (Papas et al, 2007).

For children, the built environment as it relates to nutrition includes both macro- and micro-level considerations. On the community, or macro level, the factors of the built environment that influence nutrition and risk factors for obesity include a greater reliance on convenience foods and fast foods, increasing portion sizes, and the food landscape (Sallis and Glanz, 2006). The food landscape evaluates the accessibility and availability of healthy foods, and it is clear that low-income neighborhoods have limited access to stores offering fruits and vegetables (Rosenkranz and Dzewaltowski, 2008).

Close proximity to fast food restaurants and convenience stores are negatively correlated with daily fruit and vegetable consumption for school age children (Timperio et al, 2008). Many urban and rural Americans live in areas termed as food deserts, which are defined as having limited access to affordable and nutritious foods. The inability to easily obtain nutritious foods has been identified as a contributing factor to the development of obesity and obesity-related diseases (USDA, 2009). About 2.2% of American households live more than 1 mile from a supermarket and do not have access to a car.

The factors on the macro level interact closely with those factors on the micro level. For children, the micro-level factors of the built environment that influence nutrition include the home food environment. The home food environment factors include home availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables, parent role modeling, child feeding practices, and general parenting style (Galvez, Pearl, and Yen, 2010; Rosenkranz and Dzewaltowski, 2008).

Obesity Prevention

A united national movement is underway to reduce risk factors for developing obesity in children. The current White House administration is promoting the “Let’s Move!” campaign as a comprehensive and coordinated initiative to prevent childhood obesity. The initiative emphasizes four primary components: healthy schools, access to affordable and healthy food, raising children’s physical activity levels, and empowering families to make healthy choices (White House, 2011). The CDC’s Health Protection Goal of Healthy People in Every Stage of Life for preschool-age children emphasizes early identification, tracking, prevention, and follow-up treatment of chronic diseases including obesity (CDC, 2007a). In addition, the Healthy People 2020 priority focus areas of prevention include a direct focus on achieving the goals of reducing the proportion of children who are overweight or obese, increasing the proportion of daily servings of fruits for children, and increasing the proportion of daily servings of vegetables for children.

Promoting good nutrition and dietary habits is a key to maintaining child health. The first 6 years are the most important for developing sound lifetime eating habits. Parents as primary caregivers are most influential in teaching children specific eating behaviors through their own child-feeding practices. Child feeding practices are a primary factor in the development of eating behaviors for children and include the level of control the parent or caregiver exerts over the type and amount of food the child eats, the role modeling of eating behaviors, the feeding cues given to the child, and the actual mealtime environment and routine. The resulting learned eating behaviors then follow an individual through adolescence and into adulthood.

Nutrition Assessment

Physical growth serves as an excellent measure of adequacy of the diet. Measurements of height and weight, plotted on appropriate growth curves at regular intervals, allow assessment of growth patterns. Head circumference is followed until age 3. For children 2 years and older, the body mass index (BMI) should be calculated (kilograms/[meters]2) based on the weight and height measurements. BMI for age and gender is plotted on the standardized BMI-for-age charts available through the CDC. Children falling outside the expected growth patterns can then be identified and interventions implemented (ADA, 2008).

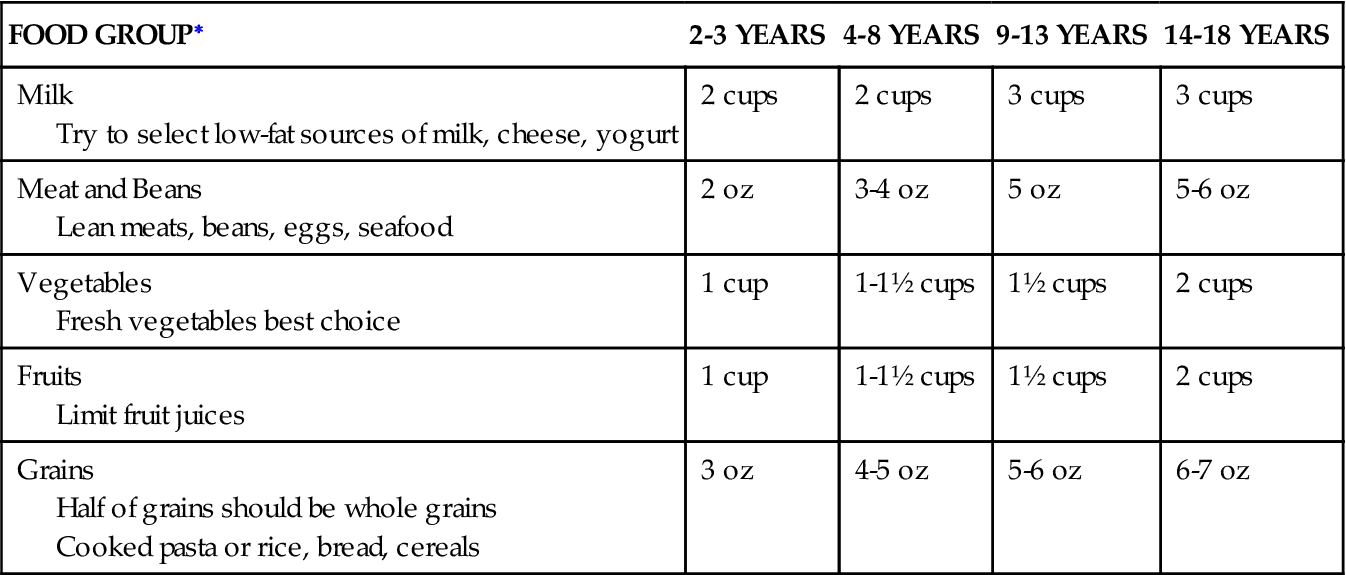

A 24-hour diet recall by the parent is a helpful screening tool to assess the amount and variety of food intake. If the recall is fairly typical for the child or adolescent, the nurse can compare the intake with basic recommendations for the child’s or adolescent’s age. It is important to ask about parent’s concerns regarding diet. It is also helpful to look at the family’s meal patterns. Other important parts of the nutrition assessment include amount of physical activity and any behavior problems that occur during meals. Table 29-3 offers guidelines to daily requirements for all ages.

TABLE 29-3

DAILY DIETARY RECOMMENDATIONS: CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE

| FOOD GROUP∗ | 2-3 YEARS | 4-8 YEARS | 9-13 YEARS | 14-18 YEARS |

| Milk Try to select low-fat sources of milk, cheese, yogurt | 2 cups | 2 cups | 3 cups | 3 cups |

| Meat and Beans Lean meats, beans, eggs, seafood | 2 oz | 3-4 oz | 5 oz | 5-6 oz |

| Vegetables Fresh vegetables best choice | 1 cup | 1-1½ cups | 1½ cups | 2 cups |

| Fruits Limit fruit juices | 1 cup | 1-1½ cups | 1½ cups | 2 cups |

| Grains Half of grains should be whole grains Cooked pasta or rice, bread, cereals | 3 oz | 4-5 oz | 5-6 oz | 6-7 oz |

∗Recommendations are per day for each group.

Adapted from U.S. Department of Agriculture: Daily Food Plan, MyPyramid.gov, 2009.

Physical Activity

Physical activity levels contribute significantly to the overall health of children, particularly related to their risk for obesity. Fewer children are meeting the recommended physical activities levels today compared with previous generations. There are several contributing factors including the physical built environment, changes in school practices for physical education, and increased time spent in monitor viewing.

Some children are at higher risk for not getting enough physical activity, particularly those children living in poverty in urban neighborhoods that are unsafe for outdoor playtime and have limited access to playgrounds and parks. Even in suburban areas, parents are wary of allowing their children to play unsupervised outdoors. Few families live in locations where they can regularly walk or bike to school or for errands. As a society, Americans have become increasing sedentary, which contributes greatly to obesity and the development of many chronic diseases.

The AAP recommends that every child and adolescent gets 60 minutes of moderate, aerobic physical activity daily. This can be accumulated throughout the day with smaller increments of activity, those obtained during school, at home, and while engaged in leisure or sports activities (AAP, 2006). It is important to encourage families to be active together since this promotes greater physical activity levels in children. It also provides family time for promoting family engagement, connection, and communication. Figure 29-6 shows developmental guidelines for physical activity promotion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree