Caring in Nursing Practice

Objectives

• Discuss the role that caring plays in building the nurse-patient relationship.

• Compare and contrast theories on caring.

• Discuss the evidence that exists about patients’ perceptions of caring.

• Explain how an ethic of care influences nurses’ decision making.

• Describe ways to express caring through presence and touch.

• Describe the therapeutic benefit of listening to patients.

• Explain the relationship between knowing a patient and clinical decision making.

Key Terms

Caring, p. 80

Comforting, p. 84

Ethic of care, p. 83

Presence, p. 83

Transcultural, p. 80

Transformative, p. 81

![]()

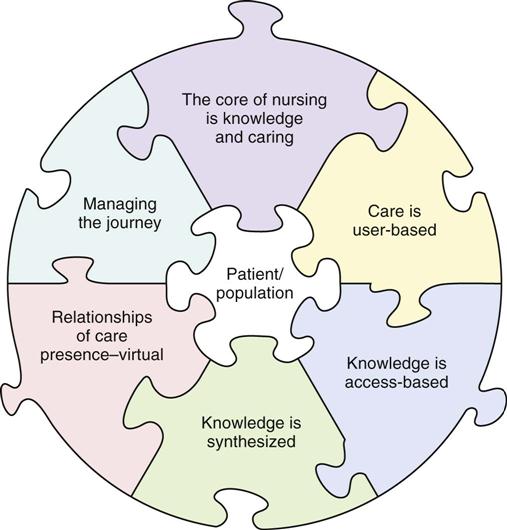

Caring is central to nursing practice, but it is even more important in today’s hectic health care environment. The demands, pressure, and time constraints in the health care environment leave little room for caring practice, which results in nurses and other health professionals becoming dissatisfied with their jobs and cold and indifferent to patient needs (Watson, 2006, 2009). Increasing use of technological advances for rapid diagnosis and treatment often causes nurses and other health care providers to perceive the patient relationship as less important. Technological advances become dangerous without a context of skillful and compassionate care. Despite these challenges, more professional organizations are stressing the importance of caring in health care. Nursing’s Agenda for the Future (ANA, 2002) states that “Nursing is the pivotal health care profession highly valued for its specialized knowledge, skill, and caring in improving the health status of the individual, family, and the community.” The American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE, 2005) describes caring and knowledge as the core of nursing, with caring being a key component of what a nurse brings to a patient experience (Fig. 7-1).

It is time to value and embrace caring practices and expert knowledge that are the heart of competent nursing practice (Benner and Wrubel, 1989; Benner et al., 2010). When you engage patients in a caring and compassionate manner, you learn that the therapeutic gain in caring makes enormous contributions to the health and well-being of your patients.

Have you ever been ill or experienced a problem requiring health care intervention? Think about that experience. Then consider the following two scenarios and select the situation that you believe most successfully demonstrates a sense of caring.

A nurse enters a patient’s room, greets the patient warmly while touching him or her lightly on the shoulder, makes eye contact, sits down for a few minutes and asks about the patient’s thoughts and concerns, listens to the patient’s story, looks at the intravenous (IV) solution hanging in the room, briefly examines the patient, and then checks the vital sign summary on the bedside computer screen before departing the room.

A second nurse enters the patient’s room, looks at the IV solution hanging in the room, checks the vital sign summary sheet on the bedside computer screen, and acknowledges the patient but never sits down or touches him or her. The nurse makes eye contact from above while the patient is lying in bed. He or she asks a few brief questions about the patient’s symptoms and leaves.

There is little doubt that the first scenario presents the nurse in specific acts of caring. The nurse’s calm presence, parallel eye contact, attention to the patient’s concerns, and physical closeness all express a person-centered, comforting approach. In contrast, the second scenario is task-oriented and expresses a sense of indifference to patient concerns. Both of these scenarios take approximately the same amount of time but leave very different patient perceptions. It is important to remember that, during times of illness or when a person seeks the professional guidance of a nurse, caring is essential in helping the individual reach positive outcomes.

Theoretical Views on Caring

Caring is a universal phenomenon influencing the ways in which people think, feel, and behave in relation to one another. Since Florence Nightingale, nurses have studied caring from a variety of philosophical and ethical perspectives. A number of nursing scholars have developed theories on caring because of its importance to nursing practice. This chapter does not detail all of the theories of caring, but it is designed to help you understand how caring is at the heart of a nurse’s ability to work with all patients in a respectful and therapeutic way.

Caring Is Primary

Benner offers nurses a rich, holistic understanding of nursing practice and caring through the interpretation of expert nurses’ stories. After listening to nurses’ stories and analyzing their meaning, she described the essence of excellent nursing practice, which is caring. The stories revealed the nurses’ behaviors and decisions that expressed caring. Caring means that persons, events, projects, and things matter to people (Benner and Wrubel, 1989; Benner et al., 2010). It is a word for being connected.

Caring determines what matters to a person. It underlies a wide range of interactions, from parental love to friendship, from caring for one’s work to caring for one’s pet, to caring for and about one’s patients. Benner and Wrubel (1989) note: “Caring creates possibility.” Personal concern for another person, an event, or thing provides motivation and direction for people to care. Caring as a professional framework has practical implications for transforming nursing practice (Drenkard, 2008). Through caring, nurses help patients recover in the face of illness, give meaning to their illness, and maintain or reestablish connection. Understanding how to provide humanistic caring and compassion begins early in nursing education and continues to mature through experiential practice (Gallagher-Lepak and Kubsch, 2009).

Patients are not all the same. Each person brings a unique background of experiences, values, and cultural perspectives to a health care encounter. Caring is always specific and relational for each nurse-patient encounter. As nurses acquire more experience, they typically learn that caring helps them to focus on the patients for whom they care. Caring facilitates a nurse’s ability to know a patient, allowing the nurse to recognize a patient’s problems and find and implement individualized solutions.

Leininger’s Transcultural Caring

From a transcultural perspective, Madeleine Leininger (1991) describes the concept of care as the essence and central, unifying, and dominant domain that distinguishes nursing from other health disciplines (see Chapter 4). Care is an essential human need, necessary for the health and survival of all individuals. Care, unlike cure, helps an individual or group improve a human condition. Acts of caring refer to nurturing and skillful activities, processes, and decisions to assist people in ways that are empathetic, compassionate, and supportive. An act of caring depends on the needs, problems, and values of the patient. Leininger’s studies of numerous cultures around the world found that care helps protect, develop, nurture, and provide survival to people. It is needed for people of all cultures to recover from illness and to maintain healthy life practices.

Leininger (1991) stresses the importance of nurses’ understanding cultural caring behaviors. Even though human caring is a universal phenomenon, the expressions, processes, and patterns of caring vary among cultures (Box 7-1). Caring is very personal; thus its expression differs for each patient. For caring to be effective, nurses need to learn culturally specific behaviors and words that reflect human caring in different cultures to identify and meet the needs of all patients (see Chapter 9).

Watson’s Transpersonal Caring

Patients and their families expect a high quality of human interaction from nurses. Unfortunately many conversations between patients and their nurses are very brief and disconnected. Watson’s theory of caring is a holistic model for nursing that suggests that a conscious intention to care promotes healing and wholeness (Watson, 2005, 2010). The theory integrates the human caring processes with healing environments, incorporating the life-generating and life-receiving processes of human caring and healing for nurses and their patients (Watson, 2006). The theory describes a consciousness that allows nurses to raise new questions about what it means to be a nurse, to be ill, and to be caring and healing. The transpersonal caring theory rejects the disease orientation to health care and places care before cure (Watson, 1996, 2008). The practitioner looks beyond the patient’s disease and its treatment by conventional means. Instead, transpersonal caring looks for deeper sources of inner healing to protect, enhance, and preserve a person’s dignity, humanity, wholeness, and inner harmony (see also Chapter 4).

In Watson’s view caring becomes almost spiritual. It preserves human dignity in the technological, cure-dominated health care system (Watson, 2006). The emphasis is on the nurse-patient relationship. The focus is on the people behind the patient and nurse and the caring relationship (Table 7-1). A nurse communicates caring-healing to the patient through the consciousness of the nurse. This takes place during a single caring moment between nurse and patient. A connection forms between the one cared for and the one caring. The model is transformative because the relationship influences both the nurse and the patient for better or for worse (Watson, 2006, 2010). Caring-healing consciousness promotes healing. Application of Watson’s caring model in practice enhances nurses’ caring practices (Box 7-2).

TABLE 7-1

Watson’s 10 Carative Factors (Watson, 2005, 2008)

| CARATIVE FACTOR | EXAMPLE IN PRACTICE |

| Forming a human-altruistic value system | Use loving kindness to extend yourself. Use self-disclosure appropriately to promote a therapeutic alliance with your patient. |

| Instilling faith-hope | Provide a connection with the patient that offers purpose and direction when trying to find the meaning of an illness. |

| Cultivating a sensitivity to one’s self and to others | Learn to accept yourself and others for their full potential. A caring nurse matures into becoming a self-actualized nurse. |

| Developing a helping, trusting, human caring relationship | Learn to develop and sustain helping, trusting, authentic, caring relationships through effective communication with your patients. |

| Promoting and expressing positive and negative feelings | Support and accept your patients’ feelings. In connecting with your patients you show a willingness to take risks in sharing in the relationship. |

| Using creative problem-solving, caring processes | Apply the nursing process in systematic, scientific problem-solving decision making in providing patient-centered care. |

| Promoting transpersonal teaching-learning | Learn together while educating the patient to acquire self-care skills. The patient assumes responsibility for learning. |

| Providing for a supportive, protective, and/or corrective mental, physical, societal, and spiritual environment | Create a healing environment at all levels, physical and nonphysical. This promotes wholeness, beauty, comfort, dignity, and peace. |

| Meeting human needs | Assist patients with basic needs with an intentional care and caring consciousness. |

| Allowing for existential-phenomenological-spiritual forces | Allow spiritual forces to provide a better understanding of yourself and your patient. |

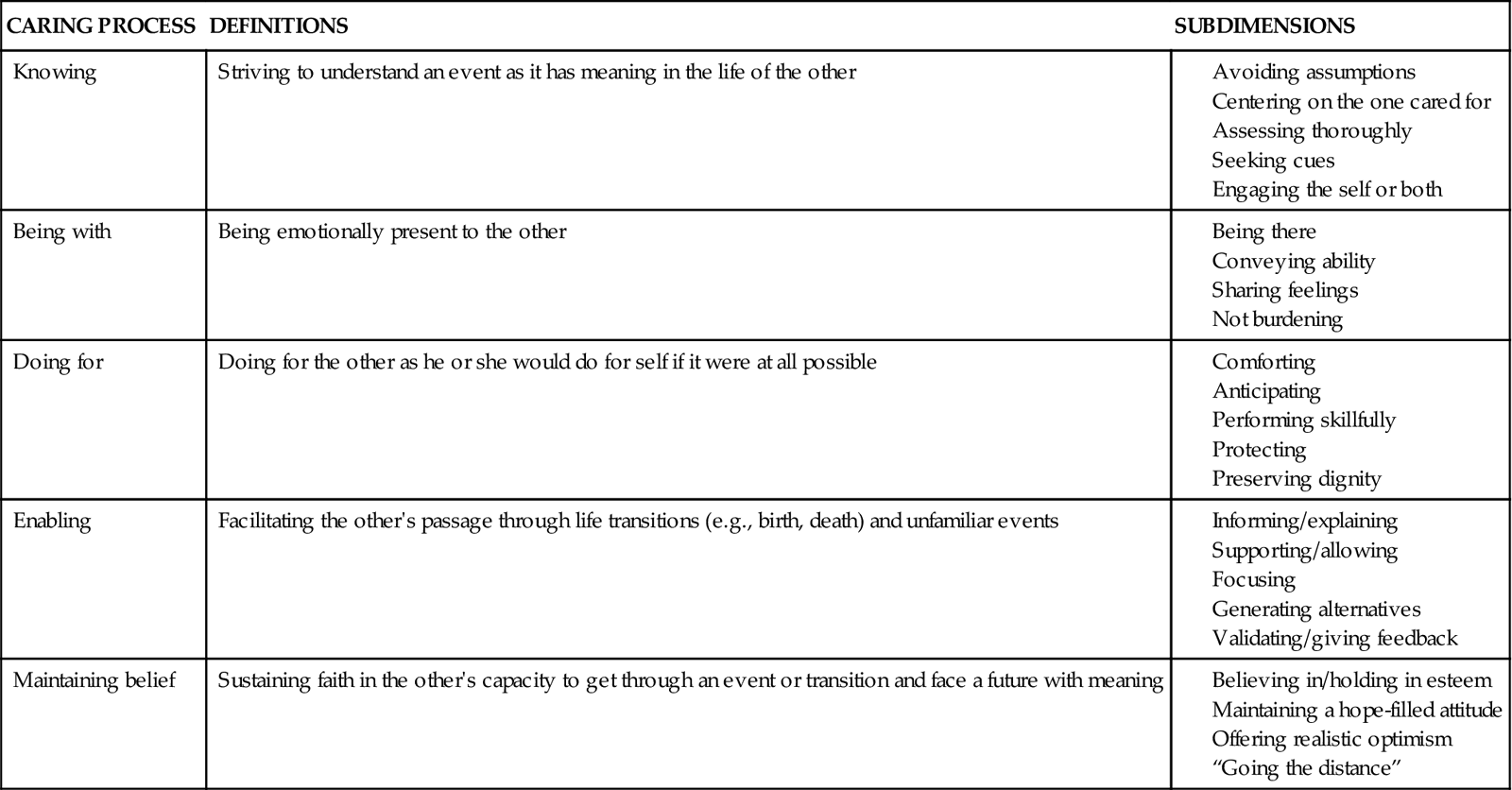

Swanson’s Theory of Caring

Kristen Swanson (1991) studied patients and professional caregivers in an effort to develop a theory of caring for nursing practice. This middle-range theory of caring was developed from three perinatal studies that interviewed women who miscarried, parents and health care professionals in a newborn intensive care unit, and socially at-risk mothers who received long-term public health intervention. All groups were in a perinatal (before, during, or after the birth of a child) setting or context and experienced the phenomenon of caring. Researchers asked each group questions regarding how they experienced or expressed caring in their situations (Swanson, 1999a, 1999b). After analyzing the stories and descriptions of the three groups, Swanson developed a theory of caring. The theory describes caring as consisting of five categories or processes (Table 7-2). Swanson (1991) defines caring as a nurturing way of relating to a valued other toward whom one feels a personal sense of commitment and responsibility. This theory supports the claim that caring is a central nursing phenomenon but not necessarily unique to nursing practice.

TABLE 7-2

Swanson’s Theory of Caring (Swanson, 1991)

Swanson’s work (1991) provides direction for how to develop useful and effective caring strategies. Each of the caring processes has definitions and subdimensions that serve as the basis for nursing interventions. Nursing care and caring are crucial in making positive differences in patients’ health and well-being outcomes (Swanson, 1999a). Thus research findings develop and refine the theory and continue to guide clinical nursing practice (Andershed and Olsson, 2009). For example, Swanson (1999b) tested the effects of caring-based counseling on women’s emotional well-being in the first year after miscarrying. Caring-based counseling was significant in reducing women’s depression and anger, particularly for women in the first 4 months following miscarriage.

Summary of Theoretical Views

Nursing caring theories have common themes. Duffy, Hoskins, and Seifert (2007) identify these commonalities as human interaction or communication, mutuality, appreciating the uniqueness of individuals, and improving the welfare of patients and their families. Caring is highly relational. The nurse and the patient enter into a relationship that is much more than one person simply “doing tasks for” another. There is a mutual give-and-take that develops as nurse and patient begin to know and care for one another (Hudacek, 2008; Sumner, 2010). Caring theories are valuable when assessing patient perceptions of being cared for in a multicultural environment (Suliman et al., 2009). Frank (1998) described a personal situation when he was suffering from cancer: “What I wanted when I was ill was a mutual relationship of persons who were also clinician and patient.” It was important for Frank to be seen as one of two fellow human beings, not the dependent patient being cared for by the expert technical clinician.

Caring seems highly invisible at times when a nurse and patient enter a relationship of respect, concern, and support. The nurse’s empathy and compassion become a natural part of every patient encounter. However, when caring is absent, it becomes very obvious. For example, if the nurse shows disinterest or chooses to avoid a patient’s request for help, his or her inaction quickly conveys an uncaring attitude. Benner and Wrubel (1989) relate the story of a clinical nurse specialist who learned from a patient what caring is all about: “I felt that I was teaching him a lot, but actually he taught me. One day he said to me (probably after I had delivered some well-meaning technical information about his disease), ‘You’re doing an OK job, but I can tell that every time you walk in that door you’re walking out.’ ” In this nurse’s story the patient perceived that the nurse was simply going through the motions of teaching and showed little caring toward the patient. Patients quickly know when nurses fail to relate to them.

As you practice caring, your patient will sense your commitment and willingness to enter into a relationship that allows you to understand the patient’s experience of illness. In a study of oncology patients, one patient described a nurse’s caring as “putting the heart in it” and “having an investment” that makes “patients feel that you are with them” (Radwin, 2000). Thus the nurse becomes a coach and partner rather than a detached provider of care.

One aspect of caring is enabling, when a nurse and patient work together to identify alternatives in approaches to care and resources. Consider a nurse working with a patient recently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus who must learn how to administer daily insulin injections. The nurse enables the patient by providing instruction in a manner that allows the patient to successfully adapt diabetes management strategies such as self-medication, exercise, and diet to his own lifestyle.

Another common theme of caring is to understand the context of a person’s life and illness. It is difficult to show caring for another individual without gaining an understanding of who the person is and his or her perception of the illness. Exploring the following questions with your patients helps you understand their perceptions of illness: How was your illness first recognized? How do you feel about the illness? How does your illness affect your daily life practices? Knowing the context of a patient’s illness helps you choose and individualize interventions that will actually help the patient. This approach is more successful than simply selecting interventions on the basis of your patient’s symptoms or disease process.

Patients’ Perceptions of Caring

Leininger’s, Watson’s, and Swanson’s theories provide an excellent beginning to understanding the behaviors and processes that characterize caring. Researchers explored nursing care behaviors as perceived by patients (Table 7-3). Their findings emphasize what patients expect from their caregivers and thus provide useful guidelines for your practice. Patients continue to value nurses’ effectiveness in performing tasks; but clearly patients value the affective dimension of nursing care.

TABLE 7-3

Comparison of Research Studies Exploring Nurse Caring Behaviors (as Perceived by Patients)

| PATIENT FALLS: ACUTE CARE NURSES’ EXPERIENCES (Rush et al [2008]) | EXPLORATORY STUDY OF NURSES’ PRESENCE IN DAILY CARE ON AN ONCOLOGY UNIT (Osterman et al [2010)] | IMPORTANCE OF KNOWING THE PATIENT IN WEANING FROM MECHANICAL VENTILATION (Crocker and Scholes [2009]) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|