Caring for the Cancer Survivor

Objectives

• Discuss the concept of cancer survivorship.

• Describe the influence of cancer survivorship on patients’ quality of life.

• Discuss the effects cancer has on the family.

• Explain the nursing implications related to cancer survivorship.

Key Terms

Biological response modifiers (biotherapy), p. 90

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF), p. 92

Cancer survivor, p. 90

Chemotherapy, p. 90

Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment (CRCI), p. 92

Hormone therapy, p. 90

Neuropathy, p. 92

Oncology, p. 97

Paresthesias, p. 92

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), p. 93

Radiation therapy, p. 90

![]()

Currently there are 16 million cancer survivors in the United States; the number of survivors will continue to grow since more than 1.5 million new cases of cancer are diagnosed each year (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2010; American Cancer Society [ACS], 2011). Among children diagnosed with cancer, 81.46% survive for at least 5 years. Of adults diagnosed with cancer, 68% survive at least 5 years. The number of people surviving cancer will continue to increase as new cases are diagnosed and those already treated live longer. Cancer survivors’ health care problems have largely been ignored or misunderstood because of the belief that health problems are over for those who receive treatment, survive, and are given a “clean bill of health.” There are many different trajectories or courses for cancer survival (Box 8-1). With the advances made in early diagnosis and improved treatment, more patients are becoming long-term survivors of cancer. The major forms of cancer therapy—surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, biological response modifiers (biotherapy), and radiation therapy—often create unwanted long-term effects on tissues and organ systems that impair a person’s health and quality of life in many ways (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2006). Thus cancer survivorship has enormous implications for the way these individuals monitor and manage their health throughout their lives. As a nurse, you will care for these patients when they seek care for their cancer and for other medical conditions.

The National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (2004) offers a definition of a cancer survivor: “An individual is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis, through the balance of his or her life.” Family members and friends are also survivors because they experience the effects that cancer has on their loved ones. Cancer truly is a life-changing event. Although progress is being made, evidence shows that there is a neglected phase of cancer care (i.e., the period following first diagnosis and initial treatment and before the development of a recurrence of the initial cancer or death) (IOM, 2006). In this phase many survivors do not have consistent health care follow-up. Once treatment is completed, contact with a cancer care provider often stops, and survivors’ needs go unnoticed or untreated. Despite the incredible advances made in cancer care, many long-term survivors suffer unnecessarily and die from delayed second cancer diagnoses or treatment-related chronic disease (Curtis et al., 2006).

Nurses have the responsibility to better understand the needs of cancer survivors and provide the most current evidence-based approaches for managing late and long-term effects of cancer and cancer treatment. Evidence suggests that survivors among racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations have more posttreatment symptoms and poorer treatment outcomes than Caucasians (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2004). The disparities in health among ethnic groups are related to a complex interplay of economic, social, and cultural factors, with poverty being a key factor (IOM, 2006). Being able to provide comprehensive care to a cancer survivor begins with recognizing the effects of cancer and its treatment and learning about the survivor’s own meaning of health.

The Effects of Cancer on Quality of Life

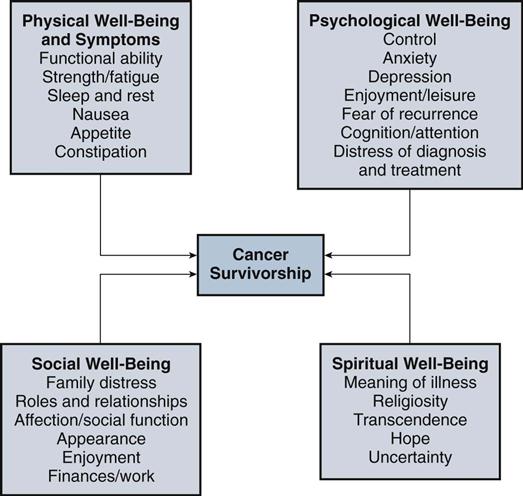

As people live longer after diagnosis and treatment for cancer, it becomes important to understand the types of distress that many survivors experience and how it affects their quality of life (Fig. 8-1). Quality of life in cancer survivorship means having a balance between the experience of increased dependence while seeking both independence and interdependence. Of course there are always exceptions in regard to the level of distress that survivors face. For some, cancer becomes an experience of self-reflection and an enhanced sense of what life is about (Box 8-2). Regardless of each survivor’s journey with cancer, having cancer affects each person’s physical, social, psychological, and spiritual well-being.

Physical Well-Being and Symptoms

Cancer survivors are at increased risk for cancer (either a recurrence of the cancer for which they were treated or a second cancer) and for a wide range of treatment-related problems (IOM, 2006). The increased risk for developing a second cancer is the result of cancer treatment, genetic factors or other susceptibility, or an interaction between treatment and susceptibility (Curtis et al., 2006). The risk for treatment-related problems is associated with the complexity of the cancer itself (e.g., type of tumor and stage of disease); the type, variety, and intensity of treatments used (e.g., chemotherapy and radiation combined); and the age and underlying health status of the patient. The following description shows how a cancer survivor’s physical health problems can be complex and burdensome.

Susan was an Army nurse who learned 7 months after discharge from the Army that she had Hodgkin’s disease. Hodgkin’s is a malignancy of lymphoid tissue. Susan received an aggressive course of treatment that included surgery, 6 months of chemotherapy, and 3 months of total lymph node irradiation. It took many months for her bone marrow to heal and blood values to return to normal. After a few years she had bilateral mastectomies for treatment-related breast cancer. She also received 3 years of immunotherapy for cancer in situ (tumor not metastasized) of the bladder. She continues to experience many noncancer conditions: premature menopause, early osteoporosis, hypothyroidism, lung fibrosis, and atrophy of neck and upper chest muscles (Leigh, 2006).

This story is not unusual among survivors and highlights the long disease course that many cancer survivors face. A number of tissues and body systems are impaired as a result of cancer and its treatment (Table 8-1). Late effects of chemotherapy and/or radiation include osteoporosis, heart failure, diabetes, amenorrhea in women, sterility in men and women, impaired gastrointestinal motility, abnormal liver function, impaired immune function, paresthesias, hearing loss, and problems with thinking and memory (IOM, 2006). Some cancer treatments cause painful peripheral neuropathy (Pignataro and Swisher, 2010). Certain conditions resolve over time, but tissue damage causes some symptoms to persist indefinitely, especially when patients receive high-dose chemotherapy. Health care professionals do not always recognize these conditions as delayed problems. Often conditions such as osteoporosis, hearing loss, or change in memory are instead considered to be age related. It is common for patients with cancer to have multiple symptoms, and more attention is being given to the existence of symptom clusters. A symptom cluster is a group of several related and coexisting symptoms such as pain-insomnia-fatigue or pain-depression-fatigue (Kirkova et al., 2010; Xiao, 2010). Researchers are trying to better understand symptom clusters, their effects on patients, and whether clusters require a different treatment approach than current symptom management.

TABLE 8-1

Examples of Late Effects of Surgery Among Adult Cancer Survivors

| Procedure | Late Effect |

| Any surgical procedure | Pain, psychosocial distress, impaired wound healing |

| Surgery involving brain or spinal cord | Impaired cognitive function, motor sensory alterations, altered vision, swallowing, language, bowel and bladder control |

| Head and neck surgery | Difficulties with communication, swallowing, and breathing |

| Abdominal surgery | Risk of intestinal obstruction, hernia, altered bowel function |

| Lung resection | Difficulty breathing, fatigue, generalized weakness |

| Prostatectomy | Urinary incontinence, sexual dysfunction, poor body image |

Modified from Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors: From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition, Washington, DC, 2006, National Academies Press.

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and associated sleep disturbances are among the most frequent and disturbing complaints of people with cancer. The symptoms often last many months after chemotherapy and radiation. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines for CRF treatment includes interventions for controlling fatigue through routine physical exercise, development of good sleep habits, eating a balanced diet, and counseling for depression that often accompanies CRF. Acupuncture may also help control CRF in cancer survivors (Johnston, Xiao, and Hui, 2007; Escalante and Manzullo, 2009).

Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) is estimated to occur in 17% to 75% of persons who receive standard-dose chemotherapy for cancer treatment (Myers, 2009). These cognitive changes occur during all phases of the cancer treatment, ranging from subtle symptoms such as a decreased attention span and being easily distracted to more obvious symptoms such as difficulty walking and significant behavior changes (Evans and Eschiti, 2009). There is no way to predict if a person will have CRCI. Some people who experience this symptom have difficulty working and processing information in their day-to-day lives, which affects daily functioning and the quality of their work and social life (Boykoff, Moieni, and Subramanian, 2009).

Often health care providers wrongly attribute the symptoms of cancer or the symptoms from the side effects of treatment to aging. This often leads to late diagnosis or a failure to provide aggressive and effective treatment of symptoms. Cancer is a chronic disease because of the serious consequences and the persistent nature of some of its late effects (IOM, 2006). The range of effects that patients suffer varies greatly. For example, a 46-year-old woman with early-stage melanoma on the right arm underwent successful surgery and only had an inconspicuous scar. In contrast, Susan, the Army nurse diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, underwent intensive chemotherapy followed by an extended course of radiation. She faced serious and substantial long-term health problems from her treatment. Patients living with cancer present significant variations in the type of conditions they develop and the length of time the conditions persist.

Numerous factors contribute to survivors not receiving timely and appropriate treatment for the physical effects they suffer. Survivors often delay reporting symptoms because they fear being perceived as ungrateful for being disease free or they fear cancer recurrence (Polomano and Farrar, 2006). Survivors are not always aware that painful conditions or syndromes are common and frequently believe that pain relief is not possible (see Chapter 43). Health care providers have limited awareness of the prevalence and incidence of pain and other symptoms among survivors and frequently have limited education in symptom management. In the case of pain management, health care providers do not always acknowledge the potential for chronic pain following curative cancer therapies, or they sometimes fail to inform patients about potential long-term consequences of cancer treatment (Polomano and Farrar, 2006). Few health care settings track the health-related quality of life and symptomatology of patients over time. Researchers are beginning to recognize the need to identify the long-term patterns of symptoms most commonly associated with types of cancer and its treatment.

Psychological Well-Being

The physical effects of cancer and its treatment sometimes extend to cause serious psychological distress (see Chapter 37). Research suggests that some long-term (10-year) cancer survivors have impaired mood but also demonstrate aspects of psychological well-being compared to a cancer-free comparison group (Costanzo, Ryff, and Singer, 2009). In addition, older survivors show resilient social well-being, spirituality, and personal growth compared to younger survivors. What creates the individual response to having cancer is unclear. Research in culturally diverse long-term adult colorectal cancer survivors associates the belief in curability of the cancer with survival of over 15 years (Soler-Vilá et al., 2009). This does not mean that, just because someone believes that his or her cancer is cured, it is; however, perhaps these people had more positive coping strategies when dealing with their cancer.

Fear of cancer recurrence is common among cancer survivors (Simard, Savard, and Ivers, 2010). Use of positive coping strategies seems to help make this fear less troublesome. The levels of this fear are higher in survivors with more negative intrusive thoughts about their illness. When cancer recurs, patients and families face new challenges and distress (Vivar et al., 2009).

Another common psychological problem for survivors is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD is a psychiatric disorder characterized by an acute emotional response to a traumatic event or situation. Approximately 3% to 4% of patients recently diagnosed with early-stage cancer experience symptoms of PTSD (e.g., grief, intrusive thoughts about the disease, nightmares, relational difficulties, or fear). This percentage increases to 35% in patients evaluated after treatment (NCI, 2009). Being unmarried or less educated or having a lower income and less social and emotional support increases the risk for PTSD (Stuber et al., 2010). The following description is an example of a cancer survivor’s response to the stressors of cancer treatment:

The first question I asked my radiation oncologist after completing treatment for nonmetastatic breast and ovarian cancer was: “When can I go back to my job?” I remember him looking at me skeptically and replying, “Considering the work you do, I would think that 8 weeks of rest and recovery is the minimum.” I left the clinic excited that my treatments were over and I could get on with my life. Eight weeks later I woke up tired after sleepless nights. I was bald and had peripheral neuropathy in my hands and feet that was crippling, and the drug I was taking made me feel like I had arthritis all over my body. Where was my energy and soft blond hair? Why couldn’t I think straight? There is no way I could do my job like this. I felt like I was drowning (Bush, 2009).

The disabling effects of chronic cancer symptoms disrupt family and personal relationships, impair individuals’ work performance, and often isolate survivors from normal social activities. Such changes in lifestyle create serious implications for a survivor’s psychological well-being. When cancer changes a patient’s body image or alters sexual function, the survivor frequently experiences significant anxiety and depression in interpersonal relationships. In the case of breast-cancer survivors, studies show that poorer self-ratings of quality of life are associated with poor body image, coping strategies, and a lack of social support (IOM, 2006).

Some factors ease the psychological stress associated with having cancer. A survivor who sees cancer as a challenging experience and a controllable threat has less stress (Jacobsen, 2006). Patients who use problem-oriented, active, and emotionally expressive coping processes also manage stress well (see Chapter 37). Survivors who have social and emotional support systems and maintain open communication with their treatment providers will also likely have less psychological distress (Jacobsen, 2006).

Social Well-Being

Cancer affects any age-group (Fig. 8-2). The developmental effects of cancer are perhaps best seen in the social impact that occurs across the life span. For adolescents and young adults, cancer seriously alters a young person’s social skills, sexual development, body image, and the ability to think about and plan for the future (see Chapter 11). Cancer interrupts their lives, causing young survivors either to feel out of touch with the interests of their peers or to perceive interests as superficial (Blum, 2006). In addition, because cancer makes them feel different, young survivors, out of fear of rejection, have problems with dating and developing new relationships. Often the course of cancer or its treatment causes young adults to delay leaving their parents. The natural separation that occurs when young adults finish school and plan to start their careers is postponed or stopped. Often a young adult then feels ill equipped to take on the real world.

Adults (ages 30 to 59) who have cancer experience significant changes in their families. Once a member of the family is diagnosed with cancer, every family member’s role, plans, and abilities changes (Blum, 2006). The healthy spouse often takes on added job responsibilities to provide additional income for the family. A spouse, sibling, grandparent, or child often assumes caregiving responsibilities for the patient. Patients who experience changes in sexuality, intimacy, and fertility see their marriages affected, often resulting in divorce.

A history of cancer significantly affects employment opportunities and the ability of a survivor to obtain and retain health and life insurance (IOM, 2006). Often a survivor experiences health-related work limitations that require a reduced work schedule or a complete change in employment. Between 64% and 84% of cancer survivors who worked before their diagnosis return to work (Steiner, Nowels, and Main, 2010). The most common problems reported by survivors who return to work are physical effort, heavy lifting, stooping, concentration, and keeping up with the work pace. Factors that affect a return to work include cancer site, prognosis, type of treatment, socioeconomic status, and characteristics of the work to be done. Middle-age cancer survivors have disability rates similar to those of people with chronic illnesses other than cancer (Short, Vasey, and Belue, 2008). The economic burden of cancer is enormous. If a survivor’s illness affects his or her ability to work, less income goes to the individual and family. In addition, high out-of-pocket expenses for prescription drugs, medical devices and supplies and expenses for coinsurance and copayments usually increase (IOM, 2006). The problems are even greater for low-income survivors if they are uninsured or underinsured. Some Americans have health insurance that provides insurance coverage for most cancer-related care. However, approximately 42 million Americans have no health insurance at all. The uninsured do not receive the care they need, they suffer from a poorer state of health, and they are more likely to die earlier than those who have insurance (IOM, 2006).

Older adults face many social concerns as a result of cancer. The disease causes some survivors to retire prematurely or decrease work hours, thus decreasing income. The older adult faces a fixed income and the limitations of Medicare reimbursement. Many older survivors see their retirement pensions erode away quickly. They often have to use their income for basic expenses and cancer care costs, thus limiting opportunities for social activities. Many older adults have moved to retirement residences in other states and find themselves isolated from the social support of their families. Older adults also face a high level of disability as a result of cancer and cancer treatment and report a higher incidence of limitations in activities of daily living than older adults without cancer (IOM, 2006). As a result, many older cancer survivors require ongoing caregiving support either from family members or professional caregivers.

Spiritual Well-Being

Cancer challenges a person’s spiritual well-being (see Chapter 35). Key features of spiritual well-being include a harmonious interconnectedness, creative energy, and a faith in a higher power or life force (Brown-Saltzman, 2006). Cancer and its treatment create physical and psychological changes that cause survivors to question, “Why me?” and wonder if perhaps their disease is some form of punishment. They often experience a level of spiritual distress, a disruption in a person’s spirit or life principle. Survivors most at risk for spiritual distress are those with energy-consuming anxiety, an inability to forgive, low self-esteem, maturational losses, and mental illness (Brown-Saltzman, 2006). Additional risk factors include poor relationships and situational losses.

Relationships with a God, a higher power, nature, family, or community are critical for survivors. Cancer threatens relationships because it makes it difficult for survivors to maintain a connection and a sense of belonging. Cancer isolates survivors from meaningful interaction and support, which then threatens their ability to maintain hope. Long-term treatment, the recurrence of cancer, and the lingering side effects of treatment all create a level of uncertainty for survivors.

Cancer and Families

A survivor’s family takes different forms: the traditional nuclear family, extended family, single-parent family, close friends, and blended families (see Chapter 10). Once cancer affects a member of the family, it affects all other members as well. Usually a member of the family becomes the patient’s caregiver. Family caregiving is a stressful experience, depending on the relationship between patient and caregiver and the nature and extent of the patient’s disease. Members of the “sandwich generation” (i.e., caregivers who are 30 to 50 years old) are often caught in the middle of caring for their own immediate family and a parent with cancer. The demands are many, from providing ongoing encouragement and support and assisting with household chores to providing hands-on physical care (e.g., bathing, assisting with toileting, or changing a dressing) when cancer is advanced. Caregiving also involves the psychological demands of communicating, problem solving, and decision making; social demands of remaining active in the community and work; and economic demands of meeting financial obligations.

Family Distress

Living through cancer and treatment is a stressful time for families. Many caregivers and cancer survivors attempt to hide cancer-related thoughts and concerns from one another, which increases adverse psychological outcomes (Langer, Brown, and Syrjala, 2009). Motivation for this behavior is often to protect one another from the distress that is experienced by each member of the family. Holding back emotions is sometimes a part of this effort to shield one another from true thoughts and feelings (Porter et al., 2009). Porter et al. found that, if cancer survivors and their partners participated in an educational program to teach the importance of disclosing feelings and then actually disclosed them, relationships and intimacy were improved. Encouraging honest communication within families is an important intervention for you to implement to enhance family relationships.

Families struggle to maintain core functions when one of their members is a cancer survivor. Core family functions include maintaining an emotionally and physically safe environment, interpreting and reducing the threat of stressful events (including the cancer) for family members, and nurturing and supporting the development of individual family members (Lewis, 2006). In childrearing families, this means providing an attentive parenting environment for children and information and support to children when their sense of well-being becomes threatened. When a member of the family has cancer, these core functions become threatened. Spouses often do not know what to do to support the survivor, and they struggle with how to help. In the end family functions become fragmented, and family members develop an uncertainty about their roles.

Implications for Nursing

Cancer survivorship creates many implications for nurses who help survivors plan for optimal lifelong health. Much needs to be done to research appropriate interventions for the effects of cancer and its treatment. Nurses are in a strong position to take the lead in improving public health efforts to manage the long-term consequences of cancer. Improvement is also necessary in the education of nurses and survivors about the phenomenon of survivorship. As a nursing student, you too can make a difference. This section addresses approaches to incorporate cancer survivorship into your nursing practice.

Survivor Assessment

Knowing that there are many cancer survivors in the health care system, consider how to assess patients who report a history of cancer. It is important to assess a cancer survivor’s needs as a standard part of your practice. When you are collecting a nursing history (see Chapter 30), explore with your patients their history of cancer, including the diagnosis and type of treatment they either are undergoing or have received in the past. Be aware that some patients do not always report that they have had cancer. Thus, when a patient tells you that he or she has had surgery, ask if it was cancer related. When a patient reveals a history of chemotherapy, radiation, biotherapy, or hormone therapy, you need to refer to resources to help you understand how these therapies typically affect patients in both the short and long term. Then extend your assessment to determine if these treatment effects exist for your patient. Consider not only the effects of the cancer and its treatment (such as potential symptoms) but how it will affect any other medical condition. For example, if a patient also has heart disease, how will cancer-related fatigue affect this individual?

Understanding the cancer experience comes from a patient’s own story. Asking general, open-ended questions about the patient’s survivor experience will help the patient reveal his or her story. For example, you might ask, “Having cancer is a journey for many. Tell me how the disease most affects you right now,” or “What are the biggest problems that you are having from cancer?” or “What can I do to help you at this point?” These types of questions focus on the area that is most important to the patient and communicate to patients your interest in their situation. Show a caring approach so patients know that their story will be accepted (see Chapter 7).

Symptom management is an ongoing problem for many cancer survivors. If cancer is their primary diagnosis, it will be natural for you to explore any presenting symptoms. Be sure to learn specifically how symptoms are affecting the patient. For example, is pain also causing fatigue, or is a neuropathy causing the patient to walk with an abnormal gait? If cancer is secondary, you do not want important symptoms to go unrecognized. Ask the patient, “Since your diagnosis of and treatment for cancer, what physical changes or symptoms have you had?” “How do these changes affect you now?” Depending on the symptoms a patient identifies, you explore each one to gain a complete picture of his or her health status (Table 8-2). Some patients are reluctant to report or discuss their symptoms. Be patient; and, once you identify a symptom, explore the extent to which the symptom is currently affecting the patient.

TABLE 8-2

Examples of Assessment Questions for Cancer Survivors