54 Care of the shock trauma patient

Compartment Syndrome: A pathologic condition caused by the progressive development of arterial compression and consequent reduction of blood supply.

Damage Control Resuscitation: A systematic approach to control bleeding at the point of injury by definitive treatment interventions of minimizing blood loss and maximizing tissue oxygenation.

Injury: A state in which a patient experiences a change in physiologic or psychological systems.

Microvascular: Pertaining to the portion of the circulatory system that is composed of the capillary network.

Motor Vehicle Crash (MVC): Occurs when a vehicle collides with another vehicle or object and can result in injuries or death.

Pattern of Injury: The circumstance in which an injury occurs, such as causation from sudden deceleration, wounding with a projectile, or crushing with a heavy object.

Permissive Hypotension: A guided intervention that limits fluid resuscitation until hemorrhage is controlled.

Primary Assessment: The first in order of importance in the evaluation or appraisal of a disease or condition.

Resuscitation: Use of emergency measures in an effort to sustain life.

Secondary Assessment: Evaluation of a disease or condition with previously compiled data.

Shock: An abnormal condition of inadequate blood flow and nutrients to the body’s tissues, with life-threatening cellular dysfunction.

Shock Trauma: A sudden disturbance that causes a wound or injury and results in acute circulatory failure.

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS): Inflammatory disturbance that affects multiple organ systems of the body.

Trauma: Tissue injury, such as a wound, burn, or fracture, or psychological injury in which personality damage can be traced to an unpleasant experience related to tissue injury, such as a wound, burn, amputation, or fracture.

Shock trauma care continues to change dramatically in response to innovative surgical technologies, advancements in anesthesia agents, and trauma research. Likewise, the medical advances continue to be driven by the state of the trauma science directly resulting from military medicine’s evolving combat casualty management from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In peacetime, the civilian trauma centers take the lead in timely research and evidence-based medicine to establish new trauma protocols and to translate the trauma research to the practice at the bedside. However, in wartime, it is military medicine’s combat medical research and scientific data outcomes that guide the cutting edge benefiting civilian trauma centers.1 The history of advancements in shock trauma care is directly linked to wars and the military’s battlefield medicine.1 Trauma care continues to advance in the twenty-first century with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Permissive hypotension and damage control hemorrhage bring new dimensions in treating severe hemorrhagic shock. Consequently, the treatment of shock is now focused on rapid transport and guided resuscitation within the “golden hour.”2 Advances in vascular surgery have led to better patient outcomes. Today, the battlefields in Iraq and Afghanistan have continued to advance shock trauma nursing care that directly correlates with enhance trauma patient outcomes.

Epidemiology of trauma

In the United States, trauma injuries continue to be the fourth leading cause of death, affecting the lives of more than 70 million people each year.3–7 Furthermore, trauma accounts for more deaths in the United States during the first four decades of life than any other disease. Surprisingly, fatality rates for older adults are now higher than rates for younger adults.5,6 Mortality from trauma is the tip of the iceberg, a small indication of a much bigger problem; many patients survive trauma, need surgical intervention, and require lengthy rehabilitation.

Although 50% of all deaths attributed to trauma occur within minutes to hours after the injury, 30% of patients die within 2 days of neurologic injury; the remaining 20% of deaths occur as a result of complications.3 Overwhelming infection and sepsis result from these traumatic injuries, and trauma patients are at risk for multiple complications, including respiratory, circulatory, neurologic, and renal failure. Numerous pathologic conditions and inflammatory derangements can contribute to this high incidence rate of late mortality from sepsis. Trauma patients who need surgery and anesthesia have greater vulnerability to life-threatening conditions and mandate vigilant, astute postanesthesia nursing care.

Prehospital phase

Mechanism of injury

The pattern or MOI simply refers to the manner in which the trauma patient was injured.8 For accurate assessment of the trauma patient in the PACU, the nurse needs a basic understanding of the different types of MOI. Patterns of injury are related to the categories of the injuring force and the subsequent tissue response. A thorough understanding of these aspects of injury helps in determining the extent and nature of the potential injuries. Damage occurs when the force deforms tissues beyond failure limits.8 Injuries result from different kinds of energy (kinetic forces, such as motor vehicle crashes [MVCs], falls, or bullets) or acute exposure (thermal, chemical, electrical, radiation, or high-yield explosives) to the tissues and underlying structures. Some of the major factors that influence the severity of the injury are the velocity of the objects and the force in terms of physical motion to moving or stationary bodies. The force is the mass of an object multiplied by the acceleration. Numerous studies conclude that the MOI helps identify common injury combinations, predict eventual outcomes, and explain the type of injury sustained.8 Although a certain pattern of injury may be predictable for specific injuries, trauma patients may sustain other injuries. A thorough assessment for identification of all actual and potential injuries is needed.8,9

Various forms of traumatic injuries are: blunt force (high-velocity); penetrating, such as those that cut or pierce; falls from great heights; firearms; and chemical, electric, radiant, and thermal burns. MVCs create impressive forces that can fracture extremities, crush organs, and lead to massive blood loss and soft tissue damage. At the time of a crash, three impacts occur: (1) vehicle to object; (2) body to vehicle; and (3) organs within body. Forces are exerted in relation to acceleration, deceleration, shearing, and compression.8,9 Acceleration-deceleration injuries occur when the head is thrown rapidly forward or backward, resulting in sudden alterations. The semisolid brain tissue moves slower than the solid skull and collides with the skull, causing injury. The injury where the brain makes contact with the skull is called a coup. The brain injury can also occur as the brain tissue is thrown in the opposite direction, causing damage in the contralateral skull surface, which is known as contrecoup injury. Ever-changing MOIs also create the need for new nursing educational programs and competencies for postanesthesia nurses to stay up to date and to advance practice.

Blunt trauma

Blunt trauma is one of the major types of trauma injuries that is best described as a wounding force that does not communicate to the outside of the body. Blunt forces produce crushing, shearing, or tearing of the tissues, both internally and externally.8–10 High-velocity MVCs and falls from great heights cause blunt-trauma injuries that are associated with direct impact, deceleration, continuous pressure, and shearing and rotary forces.8–10 These blunt-trauma injuries are usually more serious and life threatening than other types of trauma because the extent of the injuries is less obvious and diagnosis is more difficult. Because blunt-trauma injuries can leave little outward evidence of the extent of internal damage, the nurse must be extremely vigilant and astute in making observations and ongoing assessments.

When the body decelerates, the organs continue to move forward at the original speed. As the body’s organs move in the forward direction, they are torn from their attachments by rotary and shearing forces.8–10 Furthermore, blunt forces disrupt blood vessels and nerves. This MOI to the microcirculation causes widespread epithelial and endothelial damage and thus stimulates cells to release their constituents and further activates the complement, the arachidonic acid, and the coagulation cascade that activated the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. This unique inflammatory response is covered later in this chapter. Finally, blunt trauma may mask more serious complications related to the pathophysiology of the injury.

Penetrating trauma

Penetrating trauma refers to an injury produced by a foreign object, such as stab wounds and firearms. The severity of the injury produced by a foreign body is related to the underlying structures that are damaged. The MOI causes the penetration and crushing of underlying tissues and the depth and the diameter of the wound that results from penetrating trauma. Tissue damage inflicted by bullets depends on the bullet’s size, velocity, range, mass, and trajectory. Knives often cause stab wounds, but other impaling objects can cause damage. Tissue injury depends on length of the object, the force applied, and the angle of entry. These penetrating wounds cause disruption of tissues and cellular function and thus result in the introduction of debris and foreign bodies into the wound.8,10 Impaled objects are left in place until definitive surgical extraction is available because of the tamponade effect of vascular injuries. Finally, the insult to the body may occur as local ischemia or extend to a fulminant hemorrhage from these penetrating injuries.10

Contusion of tissues

When blunt trauma is significant enough to produce capillary injury and destruction, contusion of tissues occurs. Consequently, the extravasation of blood causes discoloration, pain, and swelling.8–10 If a large vessel ruptures, a hematoma may produce a distinct palpable lesion. With a massive contusion or hematoma, an increase in myofascial pressures often results in sequelae known as compartment syndrome.9,10 A compartment is a section of muscle enclosed in a confined supportive membrane called fascia; compartment syndrome is a condition in which increased pressure inside an osteofascial compartment impedes circulation and impairs capillary blood flow and cellular ischemia, resulting in an alteration in neurovascular function.9,10 This syndrome occurs more frequently in the lower leg or forearm but can occur in any fascial compartment. Damaged vessels in the ischemic muscle dilate in response to histamine and other vasoactive chemical substances, such as the arachidonic cascade and oxygen-free radicals. This dilation, with resultant leakage of fluid from capillary membrane permeability, results in increased edema and tissue pressure.9 The increased edema and pressure compress capillaries distal to the injury, impeding microvascular perfusion. These pathologic changes cause a repetitive cycle within the confined tissues, which increases swelling and leads to increased compartment pressures. Fascial compartment syndrome can be measured if indicated. Normal pressure is more than 10 mm Hg, but a reading of more than 35 mm Hg suggests possible anoxia.11,12 A fasciotomy may be indicated to prevent muscle or neurovascular damage.

Scoring systems

Numerous scoring mechanisms have been designed to assist in measuring the severity of injuries and attempt to forecast morbidities, mortalities, and the likelihood of functional outcomes. Each scoring system is unique and measures the physiologic status of the patient. Some scoring systems work better for penetrating versus blunt trauma.11,12 The PACU nurse may record the injury scoring measurement as initial baseline severity indices; however, accuracy can be limited despite the score.

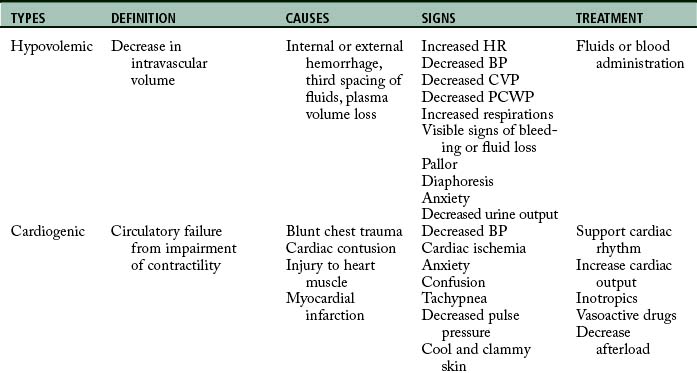

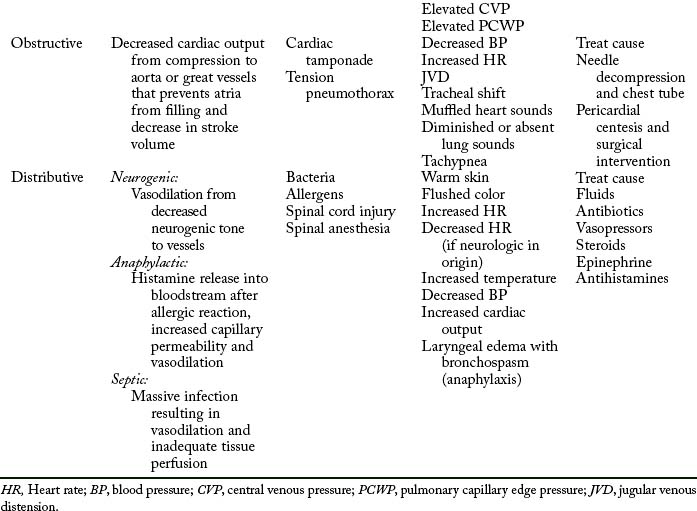

Stabilization phase

The initial assessment, resuscitation, and stabilization processes that are initiated in the emergency department and trauma center extend into the operating room (OR), the PACU, and the critical care unit. Temperature of the trauma rooms may be increased to prevent hypothermia during resuscitation. Because the most common cause of shock (Table 54-1) in the trauma patient is hypovolemia from acute blood loss, the ultimate goal in fluid resuscitation is prompt restoration of circulatory blood volume through replacement of fluids so that tissue perfusion and delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the tissues should be maintained.10–13 Rapid identification and ensuing implementation of correct aggressive treatment are vital for the trauma patient’s survival. Although hypovolemia is the most common form of shock in the trauma patient, cardiogenic shock, obstructive shock (tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade), and distributive shock (neurogenic shock, burn shock, anaphylactic shock, and septic shock) can occur. Rapid-volume infusers deliver warmed intravenous fluids at a rate of 950 mL/min with large-bore intravenous catheters.10 Many trauma centers initially infuse 2 to 3 L of lactated Ringer or normal saline solutions and then consider blood products. The fluids should be warmed to prevent or minimize hypothermia. Crystalloids, colloids, or blood products can be used for effective reversal of hypovolemia.

Crystalloids are electrolyte solutions that diffuse through the capillary endothelium and can be distributed evenly throughout the extracellular compartment. Examples of crystalloid solutions are lactated Ringer solution, Plasma-Lyte, and normal saline solution. Although controversy exists regarding crystalloid versus colloid fluid resuscitation in multiple trauma, the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma recommends that isotonic crystalloid solutions of lactated Ringer or normal saline solution be used for that purpose.11 Furthermore, crystalloids are much cheaper than colloids. Administration of crystalloids should be threefold to fourfold the blood loss.11

Colloid solutions contain protein or starch molecules or aggregates of molecules that remain uniformly distributed in fluid and fail to form a true solution.13–16 When colloid solutions are administered, the molecules remain in the intravascular space, thereby increasing the osmotic pressure gradient within the vascular compartment. Volume for volume, the half-life of colloids is much longer than that of crystalloids. Colloid solutions commonly used are plasma protein fraction, dextran, normal human serum albumin, and hetastarch.

Researchers in several new randomized control trials have used hypertonic solutions to resuscitate patients in shock.14–18 According to Beekley,18 hypertonic saline solution (3% sodium chloride) can be used in resuscitation of the child with a severe head injury because it maintains blood pressure and cerebral oxygen delivery, decreases overall fluid requirements, and results in improved overall survival rates.16 In addition, patients with low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores from head injuries have improved survival rates in the hospital.16

Although crystalloid and colloid solutions serve as primary resuscitation fluids for volume depletion, blood transfusions are necessary to restore the capacity of the blood to carry adequate amounts of oxygen. Furthermore, blood component therapy is considered after the trauma patient’s response to the initial resuscitative fluids has been evaluated.11 In an emergency, universal donor blood (type O negative for women in childbearing years) packed red blood cells can be administered for patients with exsanguinating hemorrhage. Untyped O negative whole blood can also be given to patients with an exsanguinating hemorrhage. Other blood products, such as platelets and fresh frozen plasma, may need to be given to the trauma patient because of a consumption coagulopathy. Most notable are the leukemic trauma patients with low platelet counts. With fluid resuscitation of these patients with immunosuppression, colloids are contraindicated because of the antiplatelet activity that exacerbates hemorrhaging.17 Type-specific blood often times is available within 10 minutes and is preferred over universal donor blood. Fully cross-matched blood is preferred in situations that can warrant awaiting type and cross match, which often takes up to 1 hour.10–12 Finally, the therapeutic goal of all blood component therapy is to restore the circulating blood volume and to give back other needed blood with red blood cells and clotting factors to correct coagulation deficiencies.19–22

New evidence recognizes “permissive hypotension” by keeping the patient’s systolic blood pressure at approximately 90 mm Hg correlates with better outcomes owing to conservation of important clotting factors.21 In addition, there also seems to be a protective mechanism of myocardial suppressive factors that conserve homeostasis of fluid shifts. The intent of this protective response is to prevent further hemorrhaging or bleeding out of the red blood cells and clotting factors. By sustaining the hypotension, the blood pressure supports basic perfusion until the patient is in the OR and surgically resuscitated.19,21 Damage control resuscitation and warm, fresh whole blood are now associated with better survival rates in combat-related massive hemorrhage injuries. Restoration of blood volume before homeostasis is achieved may have adverse complications of exacerbation of blood loss from increase in blood pressure.18–22

In summary, fluid resuscitation of the trauma patient is essential to ensure that adequate circulating volume and vital oxygen and nutrients are delivered to the tissues. However, new studies recommend permissive hypotension with the use of damage control resuscitation to decrease mortality and morbidity and optimize the patient’s survival.18–22 These combat-related studies are now influencing the management of civilian resuscitation of massive hemorrhage injuries in trauma centers throughout the United States.

Collaborative approach

The anesthesia provider or OR nurse communicates a comprehensive systems report to the perianesthesia nurse and verbally reviews any definitive findings of the computed tomographic scan, including whether generalized edema or lesions are found. Vital nursing information is communicated to the appropriate OR and postanesthesia nurses caring for the trauma patient. The anesthesia provider and trauma surgeon should communicate the significant findings during the intraoperative period that may be problematic during the recovery phase, what the PACU nurse should look for and report promptly to these physicians, and what the PACU nurse should do to prevent harm during the postanesthesia phase of care.23

Postanesthesia phase I

Primary assessment

Next, the postanesthesia nurse evaluates the patient’s work of breathing. While recalling the MOI, such as blunt or penetrating trauma to the chest, the nurse should be highly suspicious of pulmonary contusions, fractured ribs, or injuries from shearing forces. The nurse assesses spontaneous respirations, respiratory excursion, chest wall integrity, symmetry, depth, respiratory rate, use of accessory muscles, and the work of breathing. With palpation, the nurse should evaluate for the presence of subcutaneous emphysema, hyperresonance or dullness over the lung fields, and tracheal deviation. With auscultation, the nurse assesses the lungs for bilateral breath sounds and evaluates for adventitious breath sounds. In addition, pulse oximetry and end-tidal CO2 monitoring augment the complete respiratory assessment of the trauma patient.

The final component of the primary survey is the disability or neurologic examination. The patient’s mental status should be assessed with the AVPU (Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive) scale or the GCS. The AVPU is described as follows: A for awake and responding to nurse’s questions; V for verbal response to nurse’s questions, P for responding to pain; and U for unresponsive.10,11 The GCS is used in many PACUs for evaluating neurologic status and predicting outcomes of severe trauma. This neurologic scoring system allows for constant evaluation from field to emergency room to PACU. One must remember that anesthesia blunts the neurologic response; therefore the response is not as useful in the immediate postanesthesia period. Next, bilateral pupil response is evaluated for equality, roundness, and reactivity: brisk, slow, sluggish, or no response to light and accommodation. Before the primary assessment is complete, the PACU nurse quickly reassesses the ABCDs for stability and then is ready to receive a report from the anesthesiologist.

Anesthesia report

Another important aspect of the anesthesia report is estimated blood loss and fluid replacement, which are carefully monitored through the hemodynamic status of the trauma patient. With the use of arterial lines and pulmonary artery catheters, the anesthesiologist can closely monitor the patient’s hemodynamic status. In severe chest injuries, closed chest drainage units and auto transfusions or Cell Saver blood recovery systems can be used to conserve the vital life-sustaining resource blood. Because the goal of treatment is to keep the patient in a hyperdynamic state, the intraoperative trending should reveal that the patient is volume supported, because the body responds hypermetabolically to trauma and achieving that state ensures the delivery of oxygen and other nutrients to essential tissues in the body. End-organ perfusion is monitored and measured with the urinary output and hemodynamic monitoring. Urinary catheters are essential in management of fluids in the trauma patient and assessment of kidney function. Hemodynamic monitoring reflects the body’s hydration status and reveals the work of the heart. A detailed operative report reveals the surgical insult to the patient. It also presents a comprehensive review of all anesthetic agents that reflects a rapid sequence of induction, balanced analgesia, and heavy use of opioids, including the time these agents were given and the amount and type of muscle relaxants and reversal agents used. The anesthesia report should reveal any untoward events that occurred during surgery, such as hypothermic or hypotensive events and significant dysrhythmias, including ischemic changes.

Secondary assessment

The next areas to be inspected are the abdomen, pelvis, and genitalia. All abrasions, contusions, edema, and ecchymoses are noted. The abdomen is auscultated for bowel sounds before palpation for tenderness and rigidity. The nasogastric tube, jejunostomy, or tube drainage is examined for color, consistency, and amount of fluid. In suspected internal abdominal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage, abdominal compartment measurements should be assessed. Some common causes of abdominal compartment syndrome are pelvic fractures, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma, bowel edema from injury, septic shock, and perihepatic or retroperitoneal packing for diffuse nonsurgical bleeding. If intraabdominal hypertension or abdominal compartment syndrome are suspected or considered, the standard of care is measurement of bladder pressures.24 A catheter or similar device is connected to a pressure transducer that is connected to the urinary catheter. The urinary catheter is clamped near the connection, 50 mL of saline solution is instilled to the bladder, the transducer is leveled at the symphysis pubis, and the pressure is measured at end expiration. If the pressure is elevated, a decompression laparotomy should be performed to release the pressure that develops from bowel edema.24 The abdomen is then left open and covered with a sterile wound vacuum until the swelling has resolved and the abdomen can be closed.

The pelvis is palpated for stability and tenderness, especially over the crests and the pubis. Priapism, which is persistent abnormal erection, may be noted.10,11 In addition, preexisting genital herpes may also be present. The urinary catheter is inspected for color and amount of drainage. Urinary output should be at least 0.5 to 1.0 mL/kg/h in adults and 1 to 2 mL/kg/h in children.8 Hematuria can indicate kidney or bladder trauma. Furthermore, urinary output must be vigilantly monitored to ensure a minimum of 30 mL/h in adults so that the patient does not develop acute renal failure from rhabdomyolysis, which can occur after traumatic injuries. The vagina and rectum are checked carefully for neurologic function and bloody drainage.

Pain

Assessment and management of pain are important parts of the scope of care provided to the trauma patient in the PACU. The trauma patient may have musculoskeletal injuries or ruptured organs that cause severe pain, which may include more than the surgical site. Identification of alcohol or opioid withdrawal requires a specialized management approach and may be difficult to assess in the patient with multiple traumas during the postanesthesia period. Substance abuse pain assessment scales, such as the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment Scale and Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment Scale, are more appropriate.25 The perianesthesia nurse needs to recognize that because pain is subjective, verbal, nonverbal, and hemodynamic, changes that indicate the patient may be exhibiting signs of pain should be noted. Pain can manifest itself with increased heart rate, increased blood pressure, pallor, tachypnea, guarding or splinting, and nausea and vomiting. Pain scales should be used to augment the nursing assessment of pain.

Optimal management of acute pain may use the following techniques: (1) patient-controlled analgesia with intravenous or epidural infusions; (2) intravenous intermittent doses for pain or sedation; and (3) major plexus blocks. Guidance for medications should be based on choosing drugs that minimize cardiovascular depression and intracranial hypertension. A higher incidence rate of substance abuse, both alcohol and recreational or addictive mind-altering drugs, in the trauma patient population may require higher doses of opioids or analgesics.25,26 Other complementary techniques, such as music therapy and guided imagery, may be initiated and used as adjuncts when the trauma patient returns for subsequent surgical procedures or wound debridement. Finally, continual pain assessment is vital to the patient’s optimal care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree