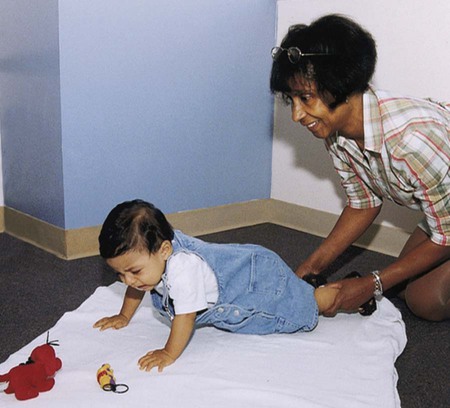

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Discuss the variety of settings in which the pediatric nurse may work 3. Describe the physical facilities of a children’s hospital unit, and explain their significance to the child’s adjustment to hospitalization 4. Discuss five measures the nurse can take to make hospitalization less threatening for the child 5. Describe how illness affects the child and family 6. Discuss the nurse’s role in a hospital admission 7. Discuss nursing implications when caring for children of different cultures and religions 8. Discuss how to perform a systems review 9. Discuss five guidelines or suggestions that may be useful to parents at discharge 10. List five safety measures applicable to the care of the child 11. Plan care for a child who is in isolation 12. Discuss care of the child before and after surgery 13. Discuss both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pediatric pain management The pediatric nurse practitioner (PNP) may care for children in the pediatric or family practice office, give routine physical examinations at the clinic, and otherwise collaborate with the physician so that a higher quality of individual care may be attained. This nurse frequently is the primary contact person for children in the health care system. The PNP may also work in school-based clinics or health centers along with school nurses and other health care providers. School-based health centers are often an ideal location to provide primary health care for children and adolescents. (Access to quality health care for all is the number-one focus area for Healthy People 2010.) The role of the school nurse has expanded at the same time that school-based health centers have increased in number (Figure 2-1). Most school-based health centers provide the basics of primary health care. Health assessments, anticipatory guidance, screenings, immunizations, acute illness care, lab services, dental care, sexually transmitted disease precautions, pregnancy testing, and family planning may be incorporated into these centers. School nurses provide health counseling and education and act as advocates for students with disabilities. School nurses and nurse practitioners also partner with community physicians and community organizations and may collaborate with state programs, such as SCHIP (State Children’s Health Insurance Program). Because hospitalizations are now briefer for most children, home care may be an acceptable alternative to a prolonged hospital stay (Figure 2-2). Technical improvements and research in specific disease entities have helped to advance the movement in home care. The result is often lower cost, increased patient satisfaction, and overall general well-being. Ongoing intravenous therapy is often maintained through home care, as is phototherapy for the newborn with jaundice. Home care, however, is not merely a matter of supplying equipment, appliances, and nursing care; it requires assessment of the total needs of children and their families. Families need to be linked to a wide variety of network services. These services are often established by a case manager, who plays a vital role in home care arrangements. Case managers oversee a continuum of care for the child by managing medical care. For families who are facing the loss of a child, hospice is a service that offers unique help. Hospice is a program offered to children who are terminally ill, usually those with only 4 to 6 months left to live. Parents, with the help of hospice nurses and caregivers, often provide the care for their dying child at home. See Chapter 22 for further discussion on hospice. Children are usually hospitalized in a pediatric hospital. They may also be hospitalized in a community hospital. Regardless of where the child is hospitalized, the pediatric setting differs in many respects from an adult setting. The pediatric unit or hospital is designed to meet the needs of children and their parents. A cheerful, casual atmosphere helps bridge the gap between home and hospital and is in keeping with the child’s emotional and physical needs. Children may wear their own clothing while they are hospitalized, and nurses wear colorful scrubs or pastel uniforms. The physical structure of a pediatric unit includes furniture of the proper height for the child, colorful furnishings, and child-friendly décor (Figure 2-3). Even transportation is suited to the child; wagons are often used to take younger children to and from procedures in the hospital setting. Most pediatric departments include a playroom in the structural plan. This room is generally equipped with toys for various age groups. Some playrooms are equipped with a fish aquarium or blossoming plants because most children love living things. Computers are also often available for use by the child. The playroom may be under the supervision of a play therapist or a child life specialist. Parents usually enjoy taking their children to the playroom and observing the various activities. The nurse should allow each child freedom to develop independently and should make observations about the child’s play. See Chapter 8 for further discussion on the value of play to the child. How a child reacts to hospitalization depends on the child’s age, preparation, previous illness-related experiences, support of family and health professionals, and the child’s emotional status. The major stressors of hospitalization include separation, loss of control, and bodily injury and pain (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). Toddlers also react to the loss of control they experience while hospitalized. According to Erikson, these children are involved in the task of autonomy. (See Chapter 4 for further discussion.) Activity limits, decreased opportunities for choices, and interrupted rituals contribute to a feeling of powerlessness. It is not unusual for toddlers to respond to this feeling with regression. They abandon recently acquired skills and may demand assistance with tasks that they have previously mastered. Without preparation for this, parents often do not understand the child’s behavior. They need to be reminded that in this situation, this is normal behavior. Parents, however, do need to reinforce appropriate behavior, and the nurse needs to maintain a sense of sameness whenever possible. Box 2-1 lists interventions for dealing with the stressors of hospitalization. In addition, toddlers need to be allowed choices, within reason, which helps them to achieve control. However, questions such as, “Do you want to take your nap now?” could lead to answers such as, “I don’t want to take a nap.” Thus, questions such as, “Do you want to take your nap now or after a story?” are better. Sometimes limits on behavior are necessary, especially if the behavior is intolerable. Parents are encouraged to support the child and use sensible limit setting if necessary. Toddlers are encouraged to play with safe equipment used in their care, for example, tongue blades and stethoscopes. Provide other toys that are appropriate to the developmental level, such as blocks, stacking toys, balls, and wooden puzzles. Whenever possible, toddlers should also be allowed out of the crib because being confined is frustrating for little ones who have just begun to enjoy walking (Figure 2-4). Supervised playroom activity contributes to intellectual, social, and motor development. Whenever possible, treatments should be done in the treatment room. The child’s room should remain a “safe place,” and the playroom should never be used for anything but play. One of the major ways preschoolers cope with their environment is by fantasizing. Unfortunately, when in an unfamiliar environment, preschoolers’ use of fantasy also contributes to their fears. Hospitalized preschoolers often have nightmares and are afraid of the dark or of unfamiliar sights and sounds. Preschoolers may also worry that inanimate objects are alive; for this reason, they may fear hospital machinery and equipment. This causes them to feel powerless. See Chapter 8 for further discussion on the preschooler. In addition to the interventions listed in Box 2-1, nurses should use their communication skills to assist the child in dealing with feelings of separation or fear. For example, the nurse might say, “Some boys and girls feel afraid in the hospital. Do you feel that way?” This assists the child in expressing fears. Nurses and parents should not tell a child that they will return unless they definitely intend to do so. Play is important to help the child adjust to hospitalization (Figure 2-5). Through dramatic play, children can act out situations that are part of their hospital experience. Dramatic play through the use of hospital equipment enables children to “work through” emotions they may be dealing with. Giving a “shot” to a doll is an example of dramatic play. Puppets also help young children work through feelings. Nurses can encourage children to communicate through puppets; dolls and puppets may also be an avenue to play out situations with children. School-age children are in the process of developing confidence in their abilities to control their feelings and actions. Hospitalization places them in the position of feeling out of control because it interrupts their routine and limits their independence. They may demonstrate resistive behaviors and have changes in vital signs in response to stress. Anger, boredom, frustration, and disinterest are other common manifestations of loss of control in the school-age child. These children appreciate the familiarity of objects from home and should be encouraged to bring such items to the hospital (Figure 2-6). In addition to the interventions listed in Box 2-1, school-age children can benefit from drawing and talking about drawings. This activity allows them to get in touch with their feelings because they may not have the ability or vocabulary to express their fears, worries, and concerns verbally. The use of drawings allows a child to express his or her feelings in an abstract manner, and the nurse can then discuss these drawings with the child. • Assist parents in obtaining written and verbal information concerning the condition of the child and the treatment plan (Figure 2-7). • Orient the family to the hospital. • Refer parents as needed to social services to assist in areas of medical expenses, food, and lodging. • Listen to parents’ concerns, and clarify information. • Involve parents in the care of the child. • Reinforce positive parenting. • Keep siblings informed of the child’s illness and progress. • Allow siblings to visit the hospitalized child. • Encourage siblings to provide pictures, make cards, and call. • Allow siblings to assist with the care of the ill child if they seem comfortable doing so and if the child’s condition permits (Figure 2-8). The admission form asks about the child’s statistical information, health history, family history, lifestyle, and home routine. This includes questions about nutrition, elimination, sleep, activity, previous hospitalization, terminology used by the child, and so on. The questions are generally directed to the parent; the child can help answer if old enough. The nurse also inquires about the use of medications at home, including complementary medicine. Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) is often used by parents with conventional treatments; the nurse needs to document the use of any alternative medicine products including herbs because of potential drug interactions or surgical complications (Box 2-2 and Table 2-1).

Care of the Child with Medical/Surgical Needs

Health Care Delivery Settings

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

Clinics and Offices

Home Care

The Hospital Setting

The Child’s Reaction to Hospitalization

Infants and Toddlers

Preschoolers

School-Age Children

The Family’s Reaction to Hospitalization

The Nurse’s Role

Admission Process

Care of the Child with Medical/Surgical Needs

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access