46 Care of the ambulatory surgical patient

Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC): A facility that is separate from a hospital and may be on the same campus as or separate from other medical facilities.

Freestanding Ambulatory Surgery Center (FASC): Term used interchangeably with ASC.

Hospital Outpatient Department (HOPD): An area within a hospital that provides perioperative care for surgery patients who are discharged on the same day. These departments often function as a same-day admitting area for other surgical patients.

Joint Venture Surgery Center: An ambulatory surgery center that has more than one ownership entity, such as a corporation and physicians, a hospital and physicians, or a combination of all three.

Third-Party Payers: Payers that include insurance companies, health maintenance organizations, and the federal government; generally mandate that surgical procedures be performed in the appropriate lowest cost setting for payment eligibility. Thus, the trend has been to push procedures from hospitals to outpatient settings to physician offices. Ambulatory surgery and hospital industry organizations continually work with federal agencies to lobby for appropriate placement of procedures. Federal payment decisions often result in managed care companies following suit; therefore this is an important focus for administrators in all levels of health care settings.

Ambulatory surgery issues

Nursing care in this setting should promote wellness and self care to the degree possible. Patients should be continually encouraged to think positively and to provide self care as is appropriate and possible. Orem’s general theory of nursing, a three part theory regarding self care, self care deficit, and nursing system, provides the basis for determining and using the patient’s personal strengths relating to self care.1 The Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory describes nursing planning and intervention that is appropriate to the ambulatory surgical patient. The nurse calculates the patient’s self-care demand and shares with the patient what must be done to regain or promote health in relation to postoperative recovery. Nursing actions revolve around teaching the patient and family, gaining acceptance of the prescribed actions, and then assessing the degree to which the nurse feels the patient can and will comply.

Assessment and preparation of the patient

Careful preoperative selection and preparation of patients for outpatient surgery help to reduce the risks of perioperative complications. Nonetheless, many patients may have significant physical, emotional or social challenges, yet they return home soon after surgery or other procedures because of insurance requirements. In addition to systemic illnesses that limit their ability to care for themselves and possibly increase the risk of perioperative complications, many people have limited social or family support. Nurses are especially challenged to prepare these more complex patients for an early transition to home.

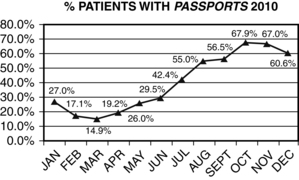

The Internet is another tool allowing patients and staff to share two-way information. Commercial and facility-developed assessment and educational tools allow patients to name their own time for providing preoperative health and demographic information. This does not preclude direct nursing interactions, but it provides a baseline from which to begin. Box 46-1 shows the work of one ambulatory surgery center to increase the use of such a tool using a quality improvement process.

BOX 46-1 Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement in the Ambulatory Surgery Center

Study objective

To increase the use of an online system for gathering patient preoperative information.

Background and reason for study

1. To obtain more accurate information when the patient has quiet time at home to concentrate on the questions

2. To reduce illegibility of patient and nurse writing

3. To reduce potential for error in transferring information from a preadmission sheet onto other chart pages (The Passport system transfers essential information such as allergies onto the admitting, anesthesia, and admitting forms.)

4. To reduce nursing time for people who have completed their Passport records ahead of the preadmission testing (PAT) call. The nurse has the data available to review and only ask questions where gaps or concerns are found.

5. To increase the ease of meeting CMS requirements for written and verbal notifications before the day of surgery

Action steps

| ACTION | RESPONSIBLE PARTY | METHOD |

|---|---|---|

| Engage all staff | Administrator, manager | Educate team, encourage all team members go online to create personal Passport record, brainstorm ideas to encourage patient and nurse use |

| Improve physician office assistance | Administrator | Create new flier and deliver to offices; ask for more direction of patients to web site by office |

| Increase e-mail notifications to patients | Administrator, schedulers, physician advocate | Encourage physician offices to secure e-mails and provide those email addresses to the ASC |

| Increase e-mail notifications to patients | Registrars | Ask patients on all business calls about e-mail address and their use; consider common scripting |

| Improve ease of web site access | Physician advocate | Meet with corporate marketing to seek better linkage |

| Improve ease of tool | Director | Remove redundant or unnecessary questions from Passport |

| Provide more encouragement to patients to use site | Registrar or PAT | Telephone assistance to get into the site, positive communication to patients |

| Encourage nurse use | Administrator | Communicate necessity to all staff members; provide reward and recognition |

| Team education | Director, administrator | Provide ongoing modules to team for understanding success factors; use graphs and support documents |

| Data sharing | Information systems support | Provide information on usage; track improvements |

| Tracking and team education | Administrators, nurse managers | Ongoing review of processes and ways to encourage patients to use the online system |

| Assignment change | Manager | Change in process to move a specific nurse into PAT role on weekly basis |

A report by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA)2 has identified major, intermediate, and minor clinical predictors of increased perioperative risk.

• Unstable coronary syndromes, such as acute or recent myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina, decompensated congestive heart failure, and severe dysrhythmias or valvular disease, are major predictors of perioperative risk.

• Intermediate risk factors include mild angina, prior MI determined with history or Q waves, compensated or prior heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and renal insufficiency.

• Minor risks include advanced age, abnormal electrocardiogram results, dysrhythmias, low functional capacity, history of stroke, and uncontrolled hypertension.

These factors should be considered before any surgery, but especially before elective surgery that could wait until a more stable cardiac status can be attained. Active cardiac conditions for which the ACC and AHA recommend evaluation and treatment before elective surgery include: unstable coronary syndromes, decompensated heart failure, significant arrhythmias, and severe valvular disease, although these recommendations are not specific to ambulatory surgery. The same report identifies cardiac risk based on the type of procedure as low (less than 1%) for the following noncardiac surgeries: endoscopic and superficial procedures, cataract and breast surgery, and ambulatory surgery.3 The physician will determine the need for adjunctive preoperative cardiac assessment.

With the emphasis on safety in the perioperative period, involvement of the patient as fully as possible in safety practices is prudent. Boxes 46-2 and 46-3 provide information that can help to raise the patient’s understanding and consciously set expectations that the patient and family will be part of the overall safety plan. With the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms today, prevention of surgical site infection should be a key focus for all health care providers and the patient. Evidenced-based decisions are important to help reduce the potential for surgical site infection.

BOX 46-2 Ten Tips to Keep You Safe in the Outpatient Setting

1. Be sure that everyone who cares for you identifies you by asking you to say your name and birth date and by checking your name band.

2. If you have any questions or concerns, ask a team member. Ask a family member or friend to speak for you if you are not able to do so.

3. If you believe that you are not steady on your feet, please ask us to help you. We do not want you to fall.

4. When you are asked about the medicines you take, please tell us about every medicine. Be sure to include creams, vitamins, herbs, diet supplements, and all prescription and over-the-counter medicines, including street drugs.

5. Tell us about all your allergies. Include allergies to medicines, tape, latex, shellfish, and anything else you may have reacted to in the past.

6. If you have a new prescription given to you while you are here, be sure you know what it is for, how to take it, and any possible side effects.

7. If you have any questions about a test or procedure, please ask your nurse or doctor.

8. Ask team members who have direct contact with you if they have washed their hands. It is the best way to prevent the spread of germs, and we will be glad you asked.

9. Be sure you know and understand how to take care of yourself when you go home.

10. If you notice any other safety concerns, please tell a team member so we can work to make our outpatient center a safer place for all.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree