Robin Chard

Care of Preoperative Patients

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Advances that have provided many benefits to the patient undergoing surgery include those in surgical techniques, anesthesia, pharmacology, medical devices, and supportive interventions. Research defining best practices has resulted in improved outcomes in all areas of the perioperative experience. New diagnostic and intervention devices for the use and refinement of new surgical techniques are continually being developed. Examples of such technical advances now in common use include robotics and many other types of minimally invasive surgeries (MISs). Advances in anesthetic agents and techniques improve the ways that a surgical patient is treated and has made anesthesia safer than ever before. Many procedures that used to be performed only in the operating room are now being done in other departments such as interventional radiology, cardiac catheterization, and endoscopy. These changes affect the role of the perioperative nurse and have an impact on how patient teaching is performed.

Cost-reduction policies are also a driving force for the management of the surgical patient. Shortened stays and ambulatory surgical services are common. Some patients may only be observed after surgery and may not be admitted as an inpatient. In response to the ongoing health care delivery changes and the use of multiple settings, nurses have modified their interventions, remaining focused on patient care before (preoperative), during (intraoperative), and after (postoperative) surgery. Together, these time periods are known as the perioperative experience.

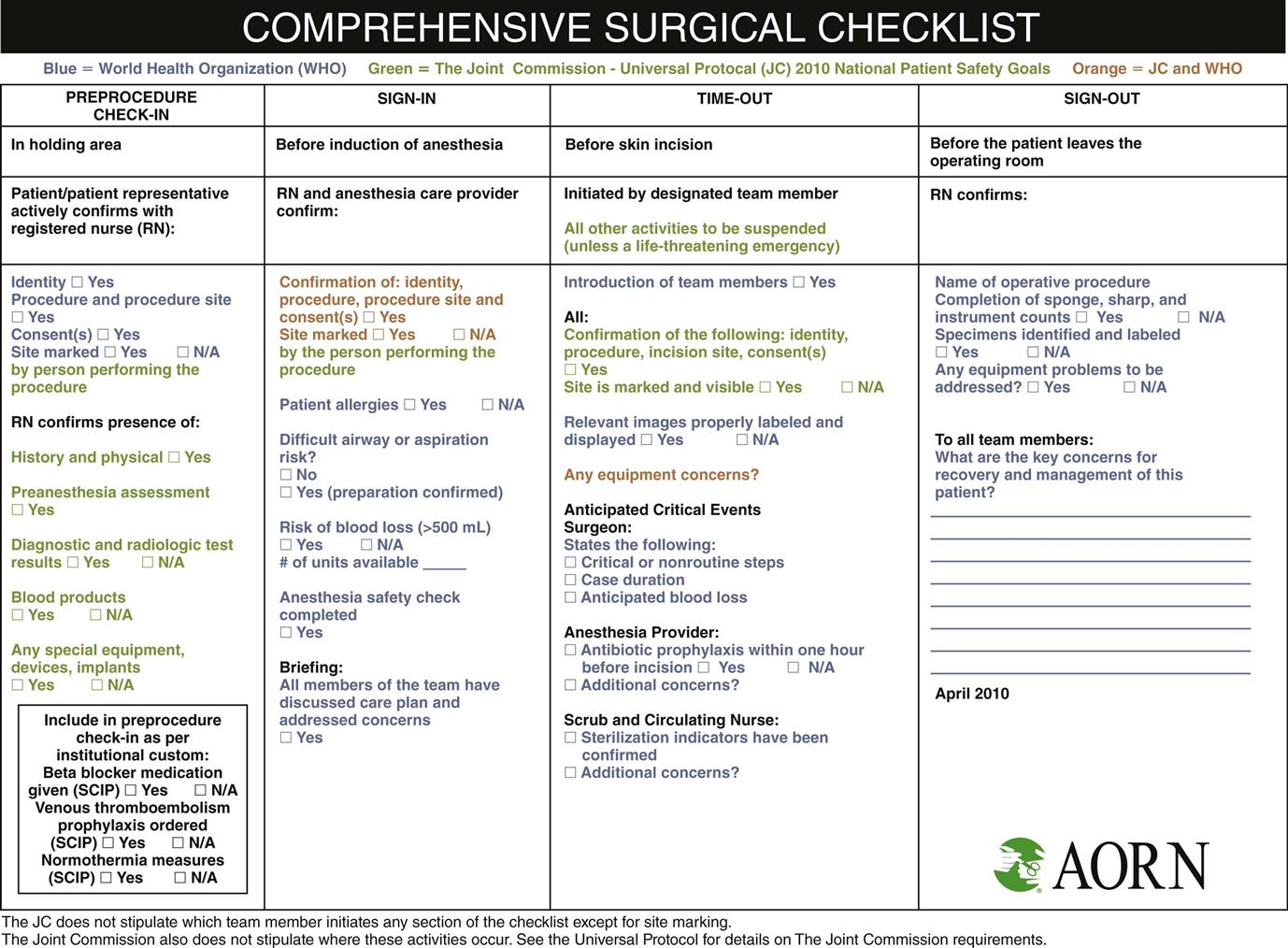

Patient safety throughout the perioperative period is the number-one priority for all personnel. Fig. 16-1 shows an overview of the preoperative activities for patient safety recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), The Joint Commission (TJC), and the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN).

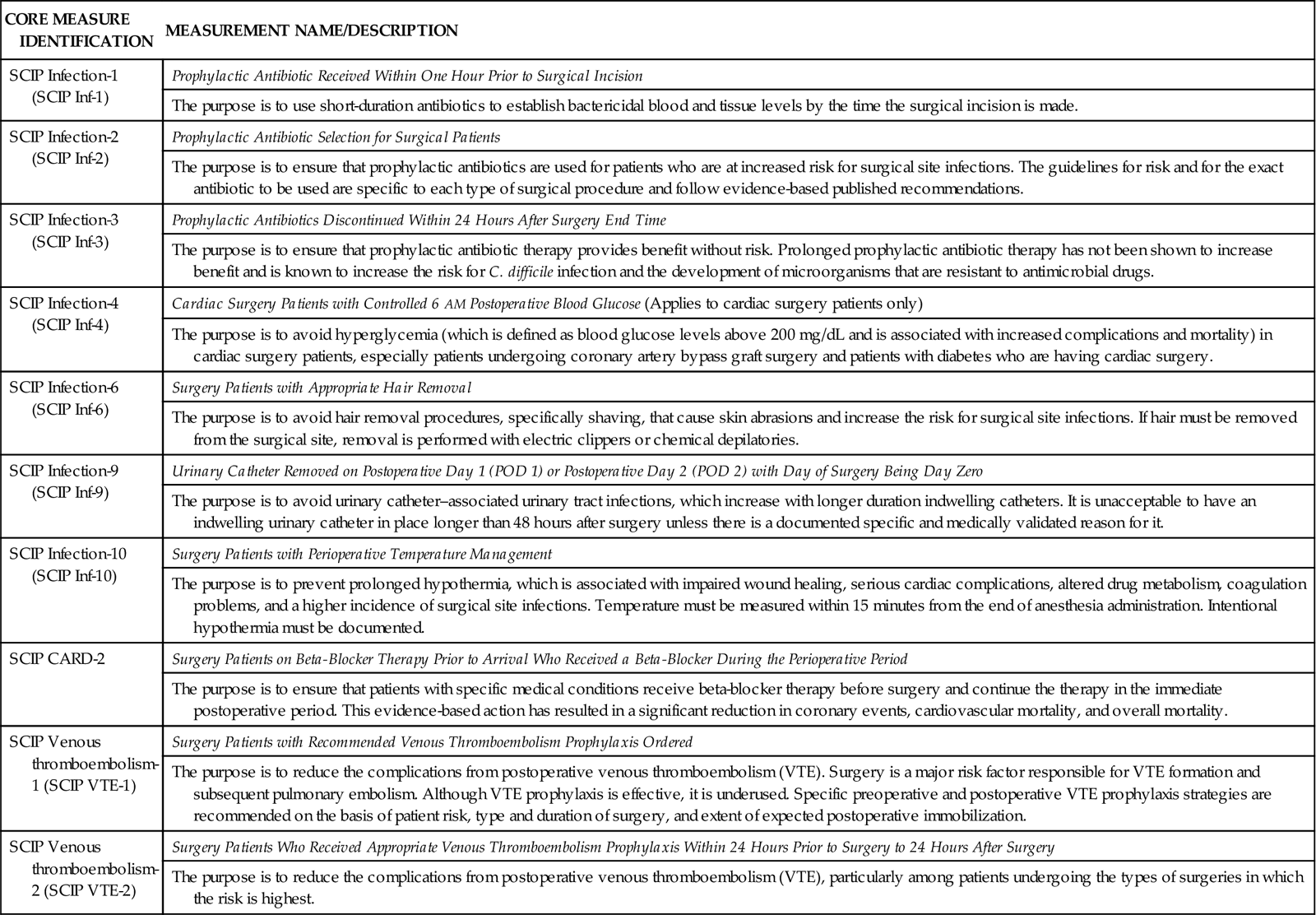

Because surgery is invasive and involves exposure to various anesthetic agents and drugs, as well as positioning and other environmental hazards, complications are common. Some complications are predictable and are considered preventable. As a result, TJC has partnered with other groups and agencies and developed a plan for the reduction and eventual elimination of preventable surgical complications known as the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP). Implementation of these core measures is now mandatory for patient safety. The current plan focuses on prevention of infection, prevention of serious cardiac events, and prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Ten specific core measures have been identified as actions required for prevention of these complications in patients identified to be at risk. Table 16-1 provides an overview of these core measure areas. (The numbers associated with the core measures are not always chronological, indicating that some areas are still in development.) The preoperative areas of responsibility for these core measures and their prevention strategies are highlighted in the appropriate areas of this chapter. In addition, some core measures are discussed in patient care chapters most associated with the complication.

TABLE 16-1

SURGICAL CARE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT CORE MEASURE OVERVIEW

| CORE MEASURE IDENTIFICATION | MEASUREMENT NAME/DESCRIPTION |

| SCIP Infection-1 (SCIP Inf-1) | Prophylactic Antibiotic Received Within One Hour Prior to Surgical Incision |

| The purpose is to use short-duration antibiotics to establish bactericidal blood and tissue levels by the time the surgical incision is made. | |

| SCIP Infection-2 (SCIP Inf-2) | Prophylactic Antibiotic Selection for Surgical Patients |

| The purpose is to ensure that prophylactic antibiotics are used for patients who are at increased risk for surgical site infections. The guidelines for risk and for the exact antibiotic to be used are specific to each type of surgical procedure and follow evidence-based published recommendations. | |

| SCIP Infection-3 (SCIP Inf-3) | Prophylactic Antibiotics Discontinued Within 24 Hours After Surgery End Time |

| The purpose is to ensure that prophylactic antibiotic therapy provides benefit without risk. Prolonged prophylactic antibiotic therapy has not been shown to increase benefit and is known to increase the risk for C. difficile infection and the development of microorganisms that are resistant to antimicrobial drugs. | |

| SCIP Infection-4 (SCIP Inf-4) | Cardiac Surgery Patients with Controlled 6 AM Postoperative Blood Glucose (Applies to cardiac surgery patients only) |

| The purpose is to avoid hyperglycemia (which is defined as blood glucose levels above 200 mg/dL and is associated with increased complications and mortality) in cardiac surgery patients, especially patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery and patients with diabetes who are having cardiac surgery. | |

| SCIP Infection-6 (SCIP Inf-6) | Surgery Patients with Appropriate Hair Removal |

| The purpose is to avoid hair removal procedures, specifically shaving, that cause skin abrasions and increase the risk for surgical site infections. If hair must be removed from the surgical site, removal is performed with electric clippers or chemical depilatories. | |

| SCIP Infection-9 (SCIP Inf-9) | Urinary Catheter Removed on Postoperative Day 1 (POD 1) or Postoperative Day 2 (POD 2) with Day of Surgery Being Day Zero |

| The purpose is to avoid urinary catheter–associated urinary tract infections, which increase with longer duration indwelling catheters. It is unacceptable to have an indwelling urinary catheter in place longer than 48 hours after surgery unless there is a documented specific and medically validated reason for it. | |

| SCIP Infection-10 (SCIP Inf-10) | Surgery Patients with Perioperative Temperature Management |

| The purpose is to prevent prolonged hypothermia, which is associated with impaired wound healing, serious cardiac complications, altered drug metabolism, coagulation problems, and a higher incidence of surgical site infections. Temperature must be measured within 15 minutes from the end of anesthesia administration. Intentional hypothermia must be documented. | |

| SCIP CARD-2 | Surgery Patients on Beta-Blocker Therapy Prior to Arrival Who Received a Beta-Blocker During the Perioperative Period |

| The purpose is to ensure that patients with specific medical conditions receive beta-blocker therapy before surgery and continue the therapy in the immediate postoperative period. This evidence-based action has resulted in a significant reduction in coronary events, cardiovascular mortality, and overall mortality. | |

| SCIP Venous thromboembolism-1 (SCIP VTE-1) | Surgery Patients with Recommended Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis Ordered |

| The purpose is to reduce the complications from postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE). Surgery is a major risk factor responsible for VTE formation and subsequent pulmonary embolism. Although VTE prophylaxis is effective, it is underused. Specific preoperative and postoperative VTE prophylaxis strategies are recommended on the basis of patient risk, type and duration of surgery, and extent of expected postoperative immobilization. | |

| SCIP Venous thromboembolism-2 (SCIP VTE-2) | Surgery Patients Who Received Appropriate Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis Within 24 Hours Prior to Surgery to 24 Hours After Surgery |

| The purpose is to reduce the complications from postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE), particularly among patients undergoing the types of surgeries in which the risk is highest. |

Information compiled from The Joint Commission. (2010). National Patient Safety Goals. Retrieved October 2010 from http://www.jointcommission.org/patientsafety/nationalpatientsafetygoals/.

Overview

The preoperative period begins when the patient is scheduled for surgery and ends at the time of transfer to the surgical suite. As a nurse, you will function as an educator, an advocate, and a promoter of health. The surgical environment demands the use of knowledge, judgment, and skills based on the principles of nursing science. Perioperative nursing places special emphasis on safety, advocacy, and patient education, although ensuring a “culture of safety” is the responsibility of all health care team members (Scherer & Fitzpatrick, 2008).

The patient’s readiness for surgery is critical to the outcome. Preoperative care focuses on preparing the patient for the surgery and patient safety. This care includes education and any intervention needed before surgery to reduce anxiety and complications and to promote patient cooperation in procedures after surgery. Use adult teaching and learning principles in teaching patients and families before surgery. Validate, clarify, and reinforce information the patient has received from the surgeon or other members of the surgical team. In addition, during the nursing assessment before surgery, problems may be identified that warrant further patient assessment or intervention before the procedure. As required by The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs), communication and collaboration with the surgical team are essential so that correct actions are taken to achieve the desired outcome.

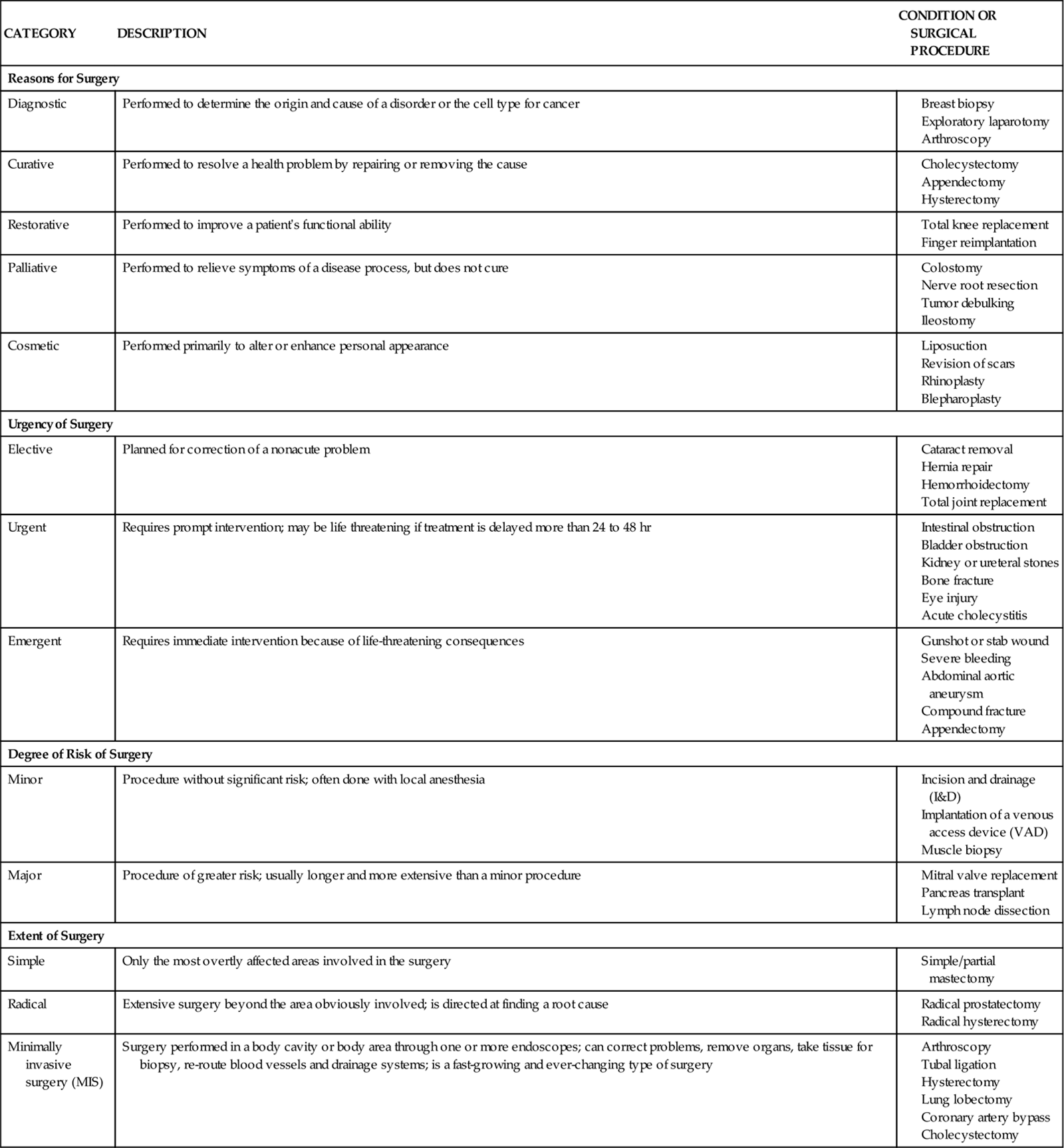

Categories and Purposes of Surgery

Surgical procedures are categorized by the purpose, body location, extent, and degree of urgency. Table 16-2 explains the categories and gives examples of surgical procedures.

TABLE 16-2

SELECTED CATEGORIES OF SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Surgical Settings

The term inpatient refers to a patient who is admitted to a hospital. The patient may be admitted the day before or, more often, the day of surgery (often termed same-day admission [SDA]), or the patient may already be an inpatient when surgery is needed. The terms outpatient and ambulatory refer to a patient who goes to the surgical area the day of the surgery and returns home on the same day (i.e., same-day surgery [SDS]). Hospital-based ambulatory surgical centers, freestanding surgical centers, physicians’ offices, and ambulatory care centers are common. More than half of all surgical procedures in North America are performed in ambulatory centers (CDC, 2008).

One advantage of outpatient surgery is that patients are not separated from the comfort and security of their home and family. With improvements in surgical techniques and anesthesia, more procedures are performed safely on an outpatient basis. Same-day surgery, however, presents new challenges for the patient who does not have an adequate or available support system. An older spouse may be unable to assist in care before or after surgery. Patients who are responsible for others may be unable to perform their usual tasks within the family. They may try to continue their family role but jeopardize their own health by doing so. As a result, their stress, fears, and anxieties about the surgical experience and about returning home immediately after surgery may increase. In these circumstances, a case manager may be assigned to coordinate post-discharge care for the patient.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Data collection about the patient before surgery begins in various settings (e.g., the surgeon’s office, the preadmission or admission office, the inpatient unit, the telephone). Use privacy to increase the patient’s comfort with the interview process. Anesthesia and surgery are both physical and emotional stressors. Collect these data:

• Age

• Use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit substances, including marijuana

• Prior surgical procedures and how these were tolerated

• Prior experience with anesthesia, pain control, and management of nausea or vomiting

• Autologous or directed blood donations

• Allergies, including sensitivity to latex products

• Knowledge about and understanding of events during the perioperative period

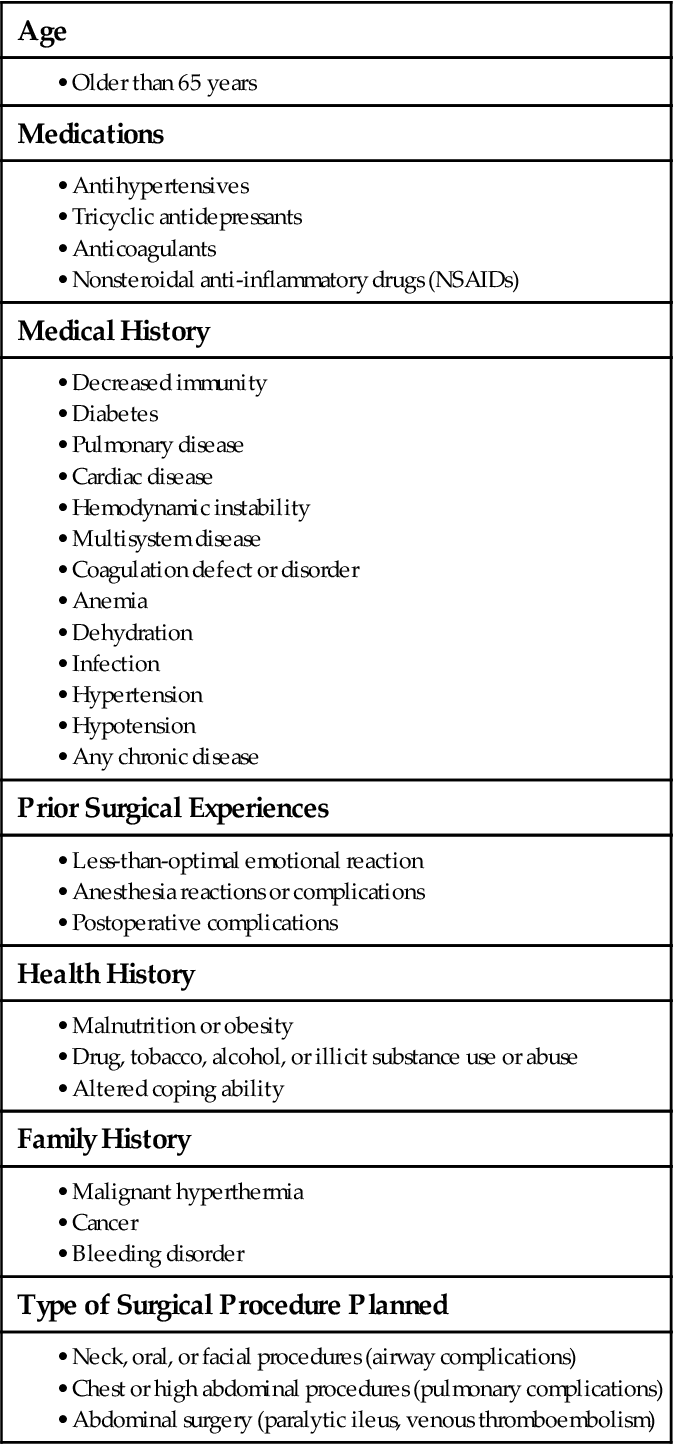

When taking a history, screen the patient for problems that increase the risk for complications during and after surgery. Some problems that increase the surgical risk or increase the risk for complications after surgery are listed in Table 16-3.

TABLE 16-3

SELECTED FACTORS THAT INCREASE SURGICAL RISK OR INCREASE THE RISK FOR POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

| Age |

| Medications |

| Medical History |

| Prior Surgical Experiences |

| Health History |

| Family History |

| Type of Surgical Procedure Planned |

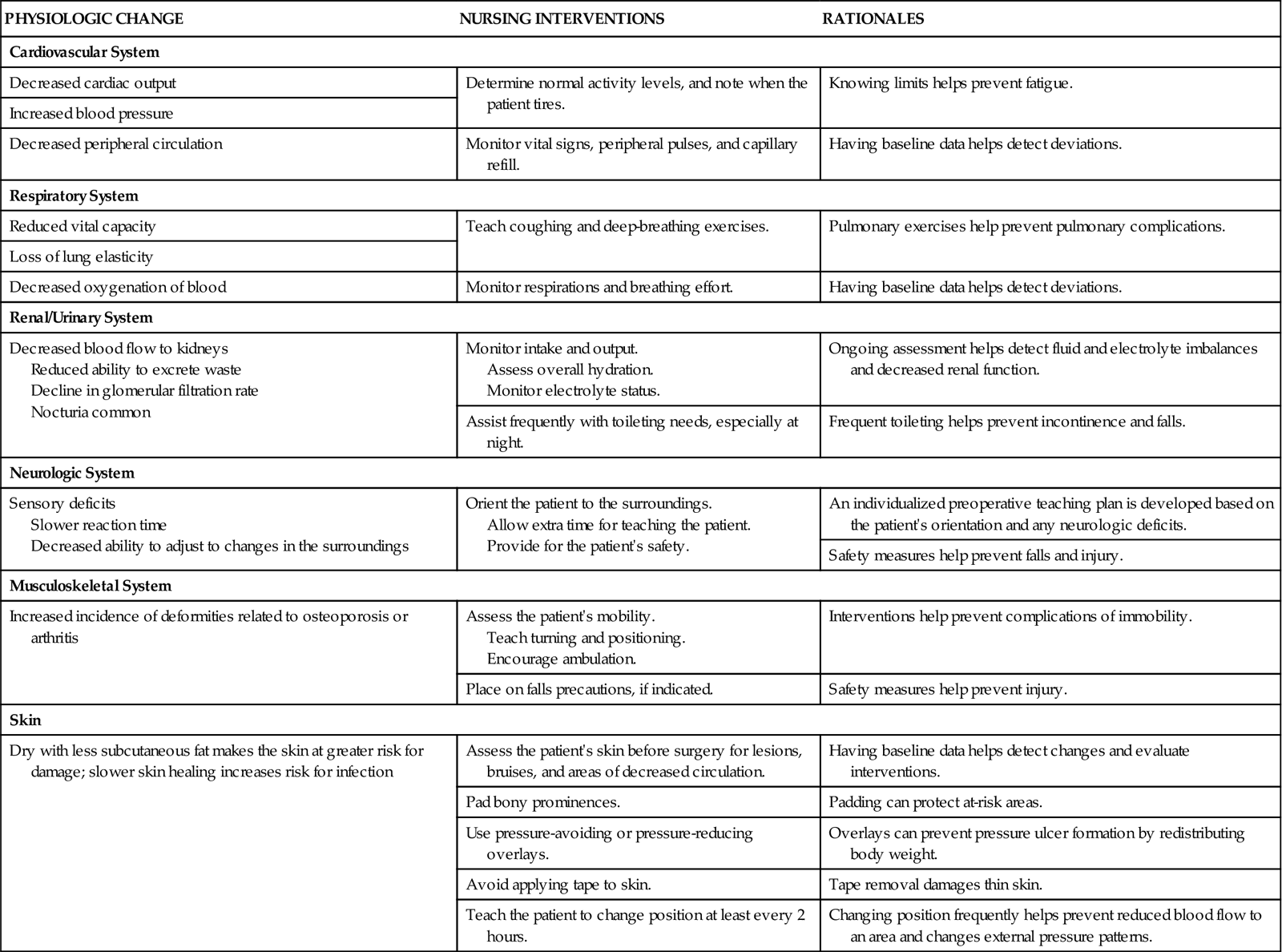

Older patients are at increased risk for complications (Doerflinger, 2009). The normal aging process decreases immune system functioning and delays wound healing. The frequency of chronic illness increases in older patients. In addition, reductions of muscle mass and body water increase the risk for dehydration. See Chart 16-1 for other changes in older adults that may alter the operative response or risk.

Drugs and substance use may affect patient responses to surgery. The use of tobacco increases the risk for pulmonary complications because of changes it causes to the lungs and chest cavity. Excessive alcohol and illicit substance use can alter the patient’s responses to anesthesia and pain medication. Withdrawal of alcohol before surgery may lead to delirium tremens. Prescription and over-the-counter drugs may also affect how the patient reacts to the operative experience. Adverse effects can occur with the use of some herbs, such as those listed in Table 16-4.

TABLE 16-4

| HERB | POTENTIAL EFFECT |

| Black cohosh | Bradycardia, hypotension, joint pains |

| Bloodroot | Bradycardia, dysrhythmia, dizziness, impaired vision, intense thirst |

| Boneset | Liver toxicity, mental changes, respiratory problems |

| Coltsfoot | Fever, liver toxicity |

| Dandelion | Interactions with diuretics, increased concentration of lithium or potassium |

| Ephedra | Headache, dizziness, insomnia, tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, irritability, dry mouth |

| Feverfew | Interference with blood-clotting mechanisms |

| Garlic | Hypotension, blood-clotting inhibition, potentiation of diabetes drugs |

| Ginseng | Headache, anxiety, insomnia, hypertension, tachycardia, asthma attacks, postmenopausal bleeding |

| Goldenseal | Vasoconstriction |

| Hawthorn | Hypotension |

| Kava | Damage to the eyes, skin, liver, and spinal cord from long-term use |

| Licorice | Hyperkalemia, hypernatremia |

| Lobelia | Hearing and vision problems |

| Motherwort | Increased anticoagulation |

| Nettle | Hypokalemia |

| Senna | Potentiation of digoxin |

| St. John’s wort | Antidepressant, photosensitivity |

| Valerian root | Mild sedative or tranquilizer effect, hepatotoxicity |

Medical history is important to obtain because many chronic illnesses increase surgical risks and need to be considered when planning care (Woolger, 2008). For example, a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus may need additional drugs to offset the stress of the surgery. A patient with diabetes may need a more extensive bowel preparation because of decreased intestinal motility. An infection may need to be treated before surgery.

Ask the patient specifically about cardiac disease because complications from anesthesia occur more often in patients with cardiac problems (Morse, 2009; Johnson, 2011). A patient with a history of rheumatic heart disease may be prescribed antibiotics before surgery. Cardiac problems that increase surgical risks include coronary artery disease, angina, myocardial infarction (MI) within 6 months before surgery, heart failure, hypertension, and dysrhythmias. These problems impair the patient’s ability to withstand hemodynamic changes and alter the response to anesthesia. The risk for an MI during surgery is higher in patients who have heart problems. Patients with cardiac disease may require perioperative therapy with beta-blocking drugs, as recommended by core measures for SCIP CARD-2 (see Table 16-1).

Pulmonary complications during or after surgery are more likely to occur in older patients, those with chronic respiratory problems, and smokers because of smoking- or age-related lung changes (Doerflinger, 2009). Increased chest rigidity and loss of lung elasticity reduce anesthetic excretion. Smoking increases the blood level of carboxyhemoglobin (carbon monoxide on oxygen-binding sites of the hemoglobin molecule), which decreases oxygen delivery to organs. Action of cilia in pulmonary mucous membranes decreases, which leads to retained secretions and predisposes the patient to infection (pneumonia) and atelectasis (collapse of alveoli). Atelectasis reduces gas exchange and causes intolerance of anesthesia. It is also a common problem after general anesthesia.

Chronic lung problems such as asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis also reduce the elasticity of the lungs, which reduces gas exchange. As a result, patients with these problems have reduced tissue oxygenation.

Previous surgical procedures and anesthesia affect the patient’s readiness for surgery. Previous experiences, especially with complications, may increase anxiety about the scheduled surgery. Ask about the patient’s experience with anesthesia and all allergies. These data provide information about tolerance of and possible fears about the use of anesthesia. The family medical history and problems with anesthetics may indicate possible reactions to anesthesia, such as malignant hyperthermia (see Chapter 17).

A sensitivity or allergy to certain substances alerts you to a possible reaction to anesthetic agents or to substances that are used before or during surgery. For example, povidone-iodine (e.g., Betadine) used for skin cleansing contains the same allergens found in shellfish. Patients who are allergic to shellfish may have an adverse reaction to povidone-iodine. The patient with an allergy to bananas and other fruits may also have a latex sensitivity or allergy.

Blood donation for surgery can be made by the patient (autologous donations) a few weeks just before the scheduled surgery date. Then, if blood is needed during or after surgery, an autologous blood transfusion can be given. This practice eliminates transfusion reactions and reduces the risk for acquiring bloodborne disease.

Patients can donate their own blood up to 5 weeks before surgery if they are infection free, have a hemoglobin level greater than 11 g/dL (110 g/L), and have a physician’s prescription. Patients with cardiac disease may need additional clearance from their cardiologist before making an autologous donation. The physician may prescribe supplemental iron before the first donation. Autologous donations can be made as often as every 3 days if other criteria are met. Usually a total of 2 to 4 units are donated. The last donation cannot be made within 72 hours before surgery.

A special tag is placed on the blood bag when an autologous blood donation has been made. The blood donor center gives the patient a matching tag that he or she wears or brings to the surgical area before surgery, as required by The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs). This procedure helps ensure that patients receive only their own blood. If the blood is not used, some agencies discard it. In other agencies, the blood goes to the blood bank where it is processed into various blood components (e.g., plasma, packed cells, platelets) for infusion in other patients.

Patients may wish to have family and friends donate blood exclusively for their use, if needed. This practice (called directed blood donation) is possible only if the blood types are compatible and the donor’s blood is acceptable. Patients may fear disease transmission from unknown blood and feel more comfortable knowing who gave the blood. Many centers do not accept directed blood, stating that it gives a false sense of security. As with autologous blood donations, a special tag is attached to the blood bag. This tag notes the names of the patient and the donor and bears the patient’s signature.

Ask whether autologous or directed blood donations have been made, and document this information in the chart. It is important to know the specific blood collection center where the donation was made and whether the blood has arrived before the patient goes into surgery. The hospital receives and stores the blood units until they are used or are no longer needed. Unused blood is returned to the collection center.

Increased use of “bloodless surgery” and minimally invasive surgery provides alternatives for patients with religious or medical restrictions to blood transfusions. These programs reduce the need for transfusion during and after surgery. Some techniques used are limiting blood samples (the number of samples, as well as the volume of blood drawn per sample) before surgery and stimulating the patient’s own red blood cell production with epoetin alpha (e.g., Epogen, Procrit) before, during, and after surgery. Supplemental iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, and vitamin C may be prescribed before surgery to help red blood cell formation. Newer equipment and surgical techniques cause less blood loss than older techniques. Such advances include recycling blood suctioned during surgery and immediately transfusing it back into the patient. Assess, monitor, teach, and support the patient during the bloodless surgery process.

Discharge planning is started before surgery. Assess the patient’s home environment, self-care capabilities, and support systems and anticipate postoperative needs before surgery. All patients, regardless of how minor the procedure or how often they have had surgery, should have discharge planning. Older patients and dependent adults may need transportation referrals to and from the physician’s office or the surgical setting. A home care nurse may be needed to monitor recovery and to provide instructions. All patients with few support systems may need follow-up care at home. Some patients need a planned direct admission to a rehabilitation hospital or center for physical therapy after surgery, especially joint replacement surgery (Lucas, 2008). Shortened hospital stays require adequate discharge planning to achieve the desired outcomes after surgery.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

The preoperative patient may be any age, with a health status that varies from well to debilitated. Perform a complete assessment before surgery to obtain baseline data. During assessment, identify current health problems, potential complications related to anesthesia, and possible complications that may occur after surgery.

When beginning the assessment, obtain a complete set of vital signs. You may need to obtain vital signs several times at different time intervals for accurate baseline values. Previous vital signs from another admission (if available) are helpful to compare with current vital signs. Abnormal vital signs may require postponement of surgery until the problem is treated and the patient’s condition is stable. Also assess for anxiety, which could increase blood pressure, pulse, and respiratory rate. Document these findings as part of the overall assessment.

Throughout the physical assessment, focus on problem areas identified from the patient’s history and on all body systems affected by the surgical procedure. The older adult (Chart 16-2; see also Chapter 3) or chronically ill patient is at increased risk for complications during and after surgery. The number of serious problems (morbidity) and death (mortality) during or after surgery is higher in older and chronically ill patients (Morse, 2009).

Report any abnormal assessment findings to the surgeon and to anesthesia personnel, as required by The Joint Commission’s NPSGs. In this way, you are a proactive patient advocate exercising professional legal responsibility. Often, established protocols or care maps identify what interventions are to be performed before surgery.

Cardiovascular status is critical to assess because cardiac problems may cause as many as 30% of surgery-related deaths. Check the patient for hypertension, which is common, is often undiagnosed, and can affect the response to surgery. Cardiac assessment includes listening to heart sounds for rate, regularity, and abnormalities. Ask whether the patient has ever had a venous thromboembolism (VTE). Examine the patient’s hands and feet for temperature, color, peripheral pulses, capillary refill, and edema. Report any problems (e.g., absent peripheral pulses, pitting edema, cardiac symptoms, chest pain, shortness of breath, and dyspnea) to the physician for further assessment and evaluation. (Cardiac assessment is discussed further in Chapter 35.)

Respiratory status considers age, smoking history (including exposure to secondhand smoke), and any chronic illness (Doerflinger, 2009). Observe the patient’s posture; respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth; overall respiratory effort; and lung expansion. Document any clubbing of the fingertips (swelling at the base of the nail beds caused by a chronic lack of oxygen) or cyanosis. Auscultate the lungs to assess for any abnormal breath sounds (crackles, wheezes, rubs). (More information on respiratory assessment is found in Chapter 29.)

Kidney function affects the excretion of drugs and waste products, including anesthetic and analgesic agents. If kidney function is reduced, fluid and electrolyte balance can be altered, especially in older patients. Ask about problems such as urinary frequency, dysuria (painful urination), nocturia (awakening during nighttime sleep because of a need to void), difficulty starting urine flow, and oliguria (scant amount of urine). Ask the patient about the appearance and odor of the urine. Equally important is an assessment of usual fluid intake and degree of continence. If the patient has kidney or urinary problems, consult with the physician about further workup. (Kidney/urinary assessment is discussed further in Chapter 68.)

Kidney impairment decreases the excretion of drugs and anesthetic agents. As a result, drug effectiveness may be altered. Scopolamine (Buscopan ![]() ), morphine, other opioids, and barbiturates often cause confusion, disorientation, apprehension, and restlessness when given to patients with decreased kidney function.

), morphine, other opioids, and barbiturates often cause confusion, disorientation, apprehension, and restlessness when given to patients with decreased kidney function.

Neurologic status includes the patient’s overall mental status, level of consciousness, orientation, and ability to follow commands. This information is needed before planning preoperative teaching and care after surgery. A problem in any of these areas affects the type of care needed during the surgical experience. Determine the patient’s baseline neurologic status to be able to identify changes that may occur later. Also assess for any motor or sensory deficits. (See Chapter 43 for complete nervous system assessment.)

The usual neurologic status of a mentally impaired patient may be difficult to assess (Doerflinger, 2009; Grebe, 2007). The patient who has been independent and oriented at home may become disoriented in the hospital setting. Family members can often provide information about what the patient was like at home.

The Joint Commission’s NPSGs require that you ensure patient safety by assessing the patient’s risk for falling, especially older patients. Evaluate factors such as mental status, muscle strength, steadiness of gait, and sense of independence to determine the patient’s risk. Document the patient’s ability to ambulate and the steadiness of gait as baseline data.

Musculoskeletal status problems may interfere with positioning during and after surgery. For example, patients with arthritis may be able to assume surgical positions but have discomfort after surgery from prolonged joint immobilization. Other anatomic features, such as the shape and length of the neck and the shape of the chest cavity, may interfere with respiratory and cardiac function or require special positioning during surgery.

Ask about a history of joint replacement, and document the exact location of any prostheses. During surgery, ensure that electrocautery pads, which could cause an electrical burn, are not placed on or near the area of the prosthesis.

Nutritional status, especially malnutrition and obesity, can increase surgical risk (Woolger, 2008). Surgery increases metabolic rate and depletes potassium, vitamin C, and B vitamins, all of which are needed for wound healing and blood clotting. In malnourished patients, decreased serum protein levels slow recovery. Negative nitrogen balance may result from depleted protein stores. This problem increases the risk for skin breakdown, delayed wound healing, possible dehiscence or evisceration (see Chapter 18), dehydration, and sepsis.

Some older patients may have poor nutrition because of chronic illness, diuretic or laxative use, poor dietary planning or habits, anorexia, and lack of motivation or financial limitations (Touhy & Jett, 2010). Indications of poor fluid or nutritional status include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree