Chapter 18 Care of Postoperative Patients

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Apply concepts of sterile technique, asepsis, and Standard Precautions during wound assessment and dressing changes.

2. Use specific agency criteria for determining readiness of the patient to be discharged from the postanesthesia care unit.

3. Examine individual patient factors for potential threats to safety, especially the risk for surgical site infection and venous thromboembolism.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

4. Evaluate patient risk for complications of wound healing.

5. Provide postoperative education for patients and family members after surgery.

6. Perform an ongoing head-to-toe assessment of the postoperative patient.

7. Prioritize nursing interventions for the patient recovering from surgery and anesthesia during the first 24 hours.

8. Apply knowledge of pathophysiology to monitor the patient for the complications of shock, respiratory depression, or impaired wound healing after surgery.

9. Assess the patient’s level of postoperative pain, and evaluate his or her responses to coordinated pain management strategies and interventions.

10. Explain the actions, dosages, side effects, and nursing implications for different types of drug therapy for pain management after surgery.

11. Evaluate surgical incisions and wounds for complications.

12. Collaborate with health care team members to perform emergency care procedures for surgical wound dehiscence or wound evisceration.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The postoperative period continues after the patient’s condition is stabilized, as well as after the patient is discharged from the ambulatory surgery facility or hospital. The actual time spent away from home after surgery varies according to age, physical health, self-care ability, support systems, type and length of surgical procedure, anesthesia, any complications, and community resources. The measures recommended by the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) that were initiated during the preoperative period to prevent certain surgical complications are continued or re-evaluated during the postoperative period. (See Chapter 16 and Table 16-1 for an explanation of these measures.)

Overview

A hand-off report that meets National Patient Safety Goal 2 requires effective communication between health care professionals. It is at least a two-way verbal interaction between the health care professional giving the report and the nurse receiving it. The language used by the person or persons giving the report is clear and cannot be interpreted in more than one way. The nurse receiving the report focuses on the report and is not distracted by the environment or other responsibilities. Standardizing the information reported helps prevent omission of critical patient-centered information and helps avoid irrelevant details (Association of periOperative Registered Nurses [AORN], 2010). The receiving nurse takes the time to restate (report back) the information to verify what was said and to make certain both the reporting person and the receiving nurse have the same understanding. The receiving nurse takes the time to ask questions and the reporting professional must respond to the questions until a common understanding is established. Chart 18-1 gives an example of critical information to include in a standard hand-off report.

Chart 18-1 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Postoperative Hand-off Report

• Type and extent of the surgical procedure

• Type of anesthesia and length of time the patient was under anesthesia

• Tolerance of anesthesia and the surgical procedure

• Allergies (especially to latex or drugs)

• Any health problems or pathologic conditions

• Type and amount of IV fluids and drugs administered

• Any intraoperative complications, such as a traumatic intubation

• Preoperative drugs and patient responses

• Primary language, any sensory impairments, any communication difficulties

• Anxiety level before receiving anesthesia

• Special requests that were verbalized by the patient preoperatively

• Preoperative and intraoperative respiratory function and dysfunction

• Pertinent medical history, including substance abuse

• Location and type of incisions, dressings, catheters, tubes, drains, or packing

• Intake and output, including current IV fluid administration and estimated blood loss

• Joint or limb immobility while in the operating room, especially in the older patient

• Other intraoperative positioning that may be relevant in the postoperative phase

• Intraoperative complications, how managed, patient responses (e.g., laboratory values)

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Use the surgical team’s report to plan the care for an individual patient. After receiving the report and assessing the patient, review the medical record for information about the patient’s history, presurgical physical condition, and emotional status. If the patient remains as an inpatient, the surgical and anesthesia information is incorporated into the postoperative plan of care. Chapter 16 identifies situations that increase a patient’s risk for the potential complications listed in Table 18-1.

TABLE 18-1 GENERAL POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS OF SURGERY

| Respiratory System Complications |

| Cardiovascular Complications |

| Skin Complications |

| Gastrointestinal Complications |

| Neuromuscular Complications |

| Kidney/Urinary Complications |

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

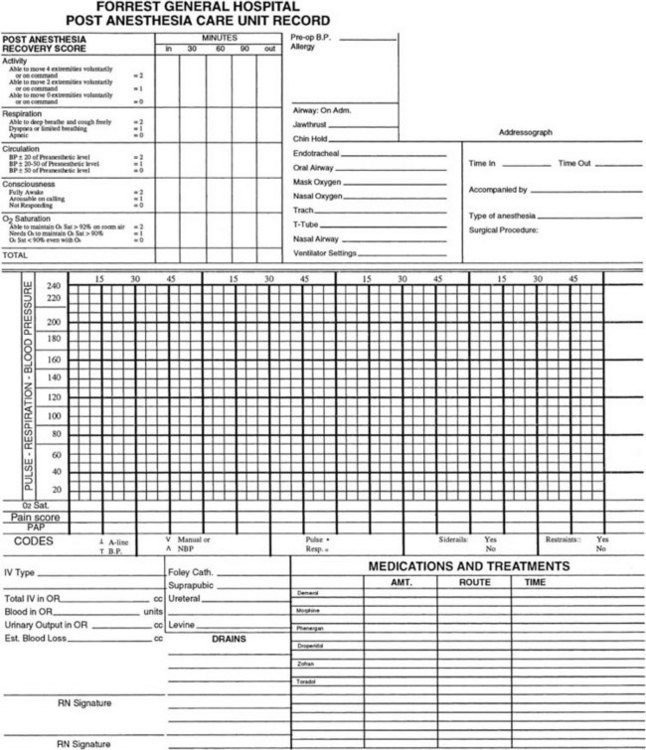

Assess the patient, and record data on a PACU flow chart record (Fig. 18-1). Assessment data include level of consciousness, temperature, pulse, respiration, oxygen saturation, and blood pressure. Examine the surgical area for bleeding. Monitor vital signs as often as your facility’s policy states, the patient’s condition warrants, and the surgeon prescribes. Once the patient is discharged from the PACU, vital signs are often measured every 15 minutes for four times, every 30 minutes for four times, every hour for four times, and then every 4 hours for 24 to 48 hours if the patient’s condition is stable. Thereafter, if the patient is admitted, vital signs are assessed according to the facility’s policy, the patient’s condition, and the nurse’s judgment.

Action Alert

The health care team determines the patient’s readiness for discharge from the PACU by the presence of a recovery score rating of 9 to 10 on the recovery scale (see Fig. 18-1). Other criteria for discharge (e.g., stable vital signs; normal body temperature; no overt bleeding; return of gag, cough, and swallow reflexes; the ability to take liquids; and adequate urine output) may be specific to the facility. After you determine that all criteria have been met, the patient is discharged by the anesthesia provider to the hospital unit or to home. If an anesthesia provider has not been involved, which may be the case with local anesthesia or moderate sedation, the surgeon or nurse discharges the patient once the discharge criteria have been met.

Assessment continues from the PACU to the intensive care or medical-surgical nursing unit. If the patient is to be discharged from the PACU to home, assessment is continued by home care nurses or by the patient or family members after health teaching. When the patient is transferred to an inpatient unit, complete an initial assessment on arrival (Chart 18-2).

The Patient on Arrival at the Medical-Surgical Unit After Discharge from the Postanesthesia Care Unit

Surgical Incision Site

Respiratory System

Critical Rescue

If the patient returns to an inpatient unit, complete an initial assessment on arrival (see Chart 18-2) and then continue to assess for respiratory depression or hypoxemia. Listen to the lungs to check for effective expansion and for abnormal breath sounds. Check the lungs at least every 4 hours during the first 24 hours after surgery and then every 8 hours, or more often, as indicated. Older patients, smokers, and patients with a history of lung disease are at greater risk for respiratory complications after surgery and need more frequent assessment (Sullivan, 2011). Obese patients are also at high risk for respiratory complications.

Cardiovascular System

Review vital signs after surgery for trends, and compare them with those taken before surgery. Report blood pressure changes that are 25% higher or lower than values obtained before surgery (or a 15- to 20-point difference, systolic or diastolic) to the anesthesia provider or the surgeon. Decreased blood pressure and pulse pressure and abnormal heart sounds indicate possible cardiac depression, fluid volume deficit, shock, hemorrhage, or the effects of drugs (see Chapters 13 and 39). Bradycardia could indicate an anesthesia effect or hypothermia. Older patients are at risk for hypothermia because of age-related changes in the hypothalamus (the temperature regulation center), low levels of body fat, and coolness of the OR suite (Touhy & Jett, 2010). An increased pulse rate could indicate hemorrhage, shock, or pain.

Peripheral vascular assessment needs to be performed because anesthesia and positioning during surgery (e.g., the lithotomy position for genitourinary procedures) may impair the peripheral circulation and contribute to venous thromboembolism (VTE), especially deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (Owens, 2008). Compare distal pulses on both feet for the quality of pulsation, observe the color and temperature of extremities, evaluate sensation, and determine the speed of capillary refill. Palpable pedal pulses indicate adequate circulation and perfusion of the legs.

In adherence to The Joint Commission’s Surgical Care Improvement Project’s (SCIP) core measures for prevention of VTE, continue the prophylactic measures initiated before surgery. Although these measures vary in type (e.g., drug therapy with anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs, sequential compression devices, antiembolic stockings or elastic wraps, early ambulation) depending on the patient’s specific risk factors and the type and extent of surgery, any preventive strategies started before surgery are usually needed for at least the first 24 hours after surgery. Reassessment of the patient’s risk for VTE and the effectiveness of the preventive strategies is performed daily. Assess the feet and legs for redness, pain, warmth, and swelling, which may occur with DVT. Foot and leg assessment may be performed once during a nursing shift, once daily, or once per visit, depending on the patient’s risk for complications and the facility’s or agency’s policy. (See Chapters 16 and 38 for more information on VTE.)

Neurologic System

Cerebral functioning and the level of consciousness or awareness must be assessed in all patients who have received general anesthesia (Table 18-2) or any type of sedation. Observe for lethargy, restlessness, or irritability, and test coherence and orientation. Determine awareness by observing responses to calling the patient’s name, touching the patient, and giving simple commands such as “Open your eyes” and “Take a deep breath.” Eye opening in response to a command indicates wakefulness or arousability but not necessarily awareness. Determine the degree of orientation to person, place, and time by asking the conscious patient to answer questions such as “What is your name?” (person), “Where are you?” (place), and “What day is it?” (time).

TABLE 18-2 IMMEDIATE POSTOPERATIVE NEUROLOGIC ASSESSMENT: RETURN TO PREOPERATIVE LEVEL

| Order of Return to Consciousness After General Anesthesia |

| Order of Return of Motor and Sensory Functioning After Local or Regional Anesthesia |

Considerations for Older Adults

For an older adult, a rapid return to his or her level of orientation before surgery may not be realistic. Preoperative drugs and anesthetics often delay the older patient’s return of orientation (see Chapters 16 and 17).

Motor function and sensory function are assessed for all patients who received general or regional anesthesia. General anesthesia depresses all voluntary motor function. Regional anesthesia alters the motor and sensory function of only part of the body. (See Chapter 17 for more information on anesthesia.) Motor and sensory assessment are very important after epidural or spinal anesthesia. Evaluate motor function by asking the patient to move each extremity. The patient who had epidural or spinal anesthesia remains in the PACU until sensory function (feeling) and voluntary motor movement of the legs have returned (see Table 18-2). Also assess the strength of each limb, and compare the results on both sides.

Test for the return of sympathetic nervous system tone by gradually elevating the patient’s head and monitoring for hypotension. Begin this evaluation after the patient’s sensation has returned to at least the spinal dermatome level of T10. (See Chapter 43 for further neurologic assessment.) After the patient is transferred to the nursing unit, continue neurologic assessment as indicated.

Fluid, Electrolyte, and Acid-Base Balance

IV fluids are closely monitored to promote fluid and electrolyte balance. Isotonic solutions such as lactated Ringer’s (LR), 0.9% sodium chloride (normal saline), and 5% dextrose with lactated Ringer’s (D5/LR) are used for IV fluid replacement in the PACU. After the patient returns to the medical-surgical unit, the type and rate of IV infusions are based on need. A typical IV solution for the patient being admitted to the nursing unit is 5% dextrose with 0.45% normal saline (D5 0.45% NS). (See Chapters 13 and 15 for further discussion of IV fluids, electrolyte balance, and hydration assessment.)

Acid-base balance is affected by the patient’s respiratory status before and during surgery; metabolic changes during surgery; and losses of acids or bases in drainage. For example, NG tube drainage or vomitus causes a loss of hydrochloric acid and leads to metabolic alkalosis. Examine arterial blood gas (ABG) values and other laboratory values. (See Chapter 14 for more detailed information on acid-base imbalances.)

Physiological Integrity

A. Compare these values with the client’s preoperative ABG values.

B. Assess the airway and notify the physician.

C. Document the values as the only action.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

21 mEq/L, Pa

21 mEq/L, Pa