Chris Winkelman

Care of Patients with Urinary Problems

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

11 Coordinate care to prevent urinary tract infections among hospitalized patients.

13 Coordinate nursing care for the patient who has invasive bladder cancer.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Renal Stone; Kidney Stone; Nephrolithiasis

Animation: Insertion of Foley Catheter

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The urinary system consists of the ureters, bladder, and urethra. Their functions are to store the urine made by the kidney and eliminate it from the body. These actions do not contribute to the homeostatic purposes of urinary elimination. However, when problems in the urinary system interfere with the mechanics of moving urine out of the body, urinary elimination is inadequate and homeostasis of fluids, electrolytes, nitrogenous wastes, and blood pressure is disrupted.

Urinary problems affect the storage or elimination of urine. Both acute and chronic urinary problems are common and costly. More than 20 million people in the United States are treated annually for urinary tract infections, cystitis, kidney and ureter stones, or urinary incontinence (U.S. Renal Data Systems, 2010). Although life-threatening complications are rare with urinary problems, patients may have significant functional, physical, and psychosocial changes that reduce quality of life. Nursing interventions are directed toward prevention, detection, and management of urologic disorders.

Infectious Disorders

Infections of the urinary tract and kidneys are common, especially among women. Manifestations of urinary tract infection (UTI) account for more than 7 million health care visits and 1 million hospital admissions annually in the United States (U.S. Renal Data Systems, 2010). UTIs are the most common health care–acquired infection. Total direct and indirect costs for adult urinary tract infections are estimated at $1.6 billion each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009).

Urinary tract infections are described by their location in the tract. Acute infections in the urinary tract include urethritis (urethra), cystitis (bladder), and prostatitis (prostate gland). Acute pyelonephritis is a kidney infection. The site of infection is important to know because site, along with the specific type of bacteria present, determines treatment. Several risk factors are associated with occurrence of UTIs (Table 69-1).

TABLE 69-1

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

| FACTOR | MECHANISM |

| Obstruction | |

| Stones (calculi) | |

| Vesicoureteral reflux | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Characteristics of urine | |

| Gender | |

| Age | |

| Sexual activity | |

| Recent use of antibiotics |

Cystitis

Pathophysiology

Cystitis is an inflammation of the bladder. It can be caused by irritation or, more commonly, by infection from bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites. Infectious cystitis is the most common of the UTIs. Noninfectious cystitis is caused by irritation from chemicals or radiation. Interstitial cystitis is an inflammatory disease that has no known cause.

Infectious agents, most commonly bacteria, move up the urinary tract from the external urethra to the bladder. Less common, spread of infection through the blood and lymph fluid can occur. Once bacteria enter the urinary tract, several factors influence the outcome (Table 69-2).

TABLE 69-2

IMPORTANT FACTORS INFLUENCING THE OUTCOME OF URINARY TRACT INFECTION

| FACILITATING ASPECTS | PROTECTIVE ASPECTS |

| Anatomy | |

| Females: Short length of the urethra and its proximity to the vagina and rectum facilitate colonization of coliform bacteria. | |

| Males: With age, the prostate enlarges and may obstruct the normal flow of urine, producing stasis. | Males: Long length of the urethra and its distance from the rectum provide protection from colonization with coliform bacteria. |

| Physiology | |

| Females: Pregnancy predisposes a woman to ureteral reflux and subsequent pyelonephritis; with age, the decline in estrogen facilitates colonization of Escherichia coli. In addition, vaginal atrophy can alter urethral competency. Males: With age, prostatic secretions lose their antibacterial characteristics and predispose to bacterial proliferation in the urine. | Females: Well-estrogenized mucosa in the urethra and trigone may inhibit bacterial colonization and enhance urogenital blood flow. Males: Normal prostatic secretions inhibit bacterial growth. Both males and females: Mucin is produced by urothelial cells lining the bladder—this helps maintain mucosal integrity and prevent cellular damage; mucin may also prevent bacteria from adhering to urothelial cells. |

| Trauma | |

| Females: Vaginal penetration with sexual intercourse may traumatize the urethra and bladder base, leading to postcoital (or “honeymoon”) cystitis; a vaginal diaphragm that is too large can place pressure on the urethra, causing trauma; vaginal childbirth can cause permanent damage to the urethra. Males: Sexually transmitted diseases may cause urethral strictures that obstruct the flow of urine and predispose to urinary stasis. Both males and females: Urethral instrumentation (e.g., catheterization) may disturb the urothelial surface and predispose to adherence of bacteria that would ordinarily not be pathogenic. | Females: Adequate lubrication, either natural or artificial, with intercourse may prevent any trauma. |

| Infectious Agent | |

| Some organisms are better able to adhere to host cells and secrete substances that induce inflammation. | A small inoculum (number of microorganisms introduced into the body) is more easily flushed away by the flow of urine. |

The presence of bacteria in the urine is bacteriuria and can occur with any urologic infection. When bacteriuria is without symptoms of infection, it is called colonization. Colonization, asymptomatic bacteriuria, is more common in older adults. This problem does not appear to progress to acute infection or kidney impairment unless the patient has other pathologic problems, and then it requires treatment.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

UTIs, like other infections, are the result of interactions between a pathogen and the host. Usually, a high bacterial virulence (ability to invade and infect) is needed to overcome normal strong host resistance. However, a compromised host is more likely to become infected even with bacteria that have low virulence. Genetically, invading bacteria with special adhesions are more likely to cause ascending UTIs that start in the urethra or bladder and move up into the ureter and kidney. Patient-specific genetic factors such as blood type and ability to produce bladder surface biofilms that protect bacteria may influence the risk for UTI (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007).

Infectious cystitis is most commonly caused by organisms from the intestinal tract. About 90% of UTIs are caused by Escherichia coli. Less common organisms include Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and organisms from the Proteus and Enterobacter species (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007).

In most cases, organisms first grow in the perineal area, then move into the urethra as a result of irritation, trauma, or catheterization of the urinary tract, and finally ascend to the bladder. Catheters are the most common factor placing patients at risk for UTIs in the hospital setting. Within 48 hours of catheter insertion, bacterial colonization begins. About 50% of patients with indwelling catheters become infected within 1 week of catheter insertion.

How a catheter-related infection occurs varies between genders. Bacteria from a woman’s perineal area are more likely to ascend to the bladder by moving along the outside of the catheter. In men, bacteria tend to gain access to the bladder from inside the lumen of the catheter. Any break in the closed urinary drainage system allows bacteria to move through the urinary tract. Best practices to reduce the risk for catheter contamination and catheter-related UTIs are listed in Chart 69-1.

Organisms other than bacteria also can cause cystitis. Fungal infections, such as those caused by Candida, can occur during long-term antibiotic therapy, because antibiotics reduce normal protective flora. Patients who are severely immunosuppressed, are receiving corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents, or have diabetes mellitus or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) are at higher risk for fungal UTIs.

Viral and parasitic infections are rare and usually are transferred to the urinary tract from an infection at another body site. For example, Trichomonas, a parasite found in the vagina, can also be found in the urine. Treatment of the vaginal infection (see Chapter 74) also resolves the UTI.

Noninfectious cystitis may result from chemical exposure, such as to drugs (e.g., cyclophosphamide [Cytoxan, Procytox ![]() ]), from radiation therapy, and from immunologic responses, as with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

]), from radiation therapy, and from immunologic responses, as with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Interstitial cystitis is a rare, chronic inflammation of the bladder, urethra, and adjacent pelvic muscles that is not a result of infection. The condition affects women ten times more often than men, and the diagnosis is difficult to make. Manifestations are similar to those of infectious cystitis with voiding occurring as often as 60 times daily, more intense urgency preceding urination, and suprapubic or pelvic pain, sometimes radiating to the groin, vulva or rectum, that is relieved by voiding. Results from urinalysis and urine culture are negative for infection (Evans & Sant, 2007; Siegel et al., 2008).

Although cystitis is not life threatening, infectious cystitis can lead to life-threatening complications, including pyelonephritis and sepsis. Severe kidney damage is a rare complication unless the patient also has other predisposing factors, such as anatomic abnormalities, pregnancy, obstruction, reflux, calculi, or diabetes.

The spread of the infection from the urinary tract to the bloodstream is termed urosepsis and is more common among older adults (Kessenich, 2010). Sepsis from any source is a systemic infection that can lead to overwhelming organ failure, shock, and death. The most common cause of sepsis in the hospitalized patient is a UTI (CDC, 2009). Sepsis has a high mortality and prolongs hospital stays (see Chapter 39).

Incidence/Prevalence

The incidence of UTI is second only to that of upper respiratory infections in primary care. Patients who have frequency (an urge to urinate frequently in small amounts), dysuria (pain or burning with urination), and urgency (the feeling that urination will occur immediately) account for more than 5 million health care visits annually. About 50% of these patients will have a confirmed UTI (U.S. Renal Data Systems, 2010).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Although cystitis is common, in many cases it is preventable. In the health care setting, reducing the use of indwelling urinary catheters is a major prevention strategy (Gray, 2010). When catheters must be used, strict attention to sterile technique during insertion can reduce the risk for UTIs as can consistent and adequate perineal and catheter care (see Chart 69-1).

Changes in fluid intake patterns, urinary elimination patterns, and hygiene patterns can help prevent or reduce cystitis in the general population. Teach all people to have a minimum fluid intake of 1.5 to 2.5 L daily unless fluid restriction is required for other health problems. Another strategy is to have sufficient fluid intake to cause 2 to 2.5 L of urine daily. Encourage people to drink more water rather than sugar-containing drinks. Teach people to avoid urinary stasis by urinating every 3 to 4 hours rather than waiting until the bladder is greatly distended. Encourage everyone either to shower daily or to wash the perineal and urethral areas daily with mild soap and a water rinse. Teach women to avoid the use of vaginal washes. Other hygiene measures that specifically reduce the risk for cystitis and other UTIs are listed in Chart 69-2.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

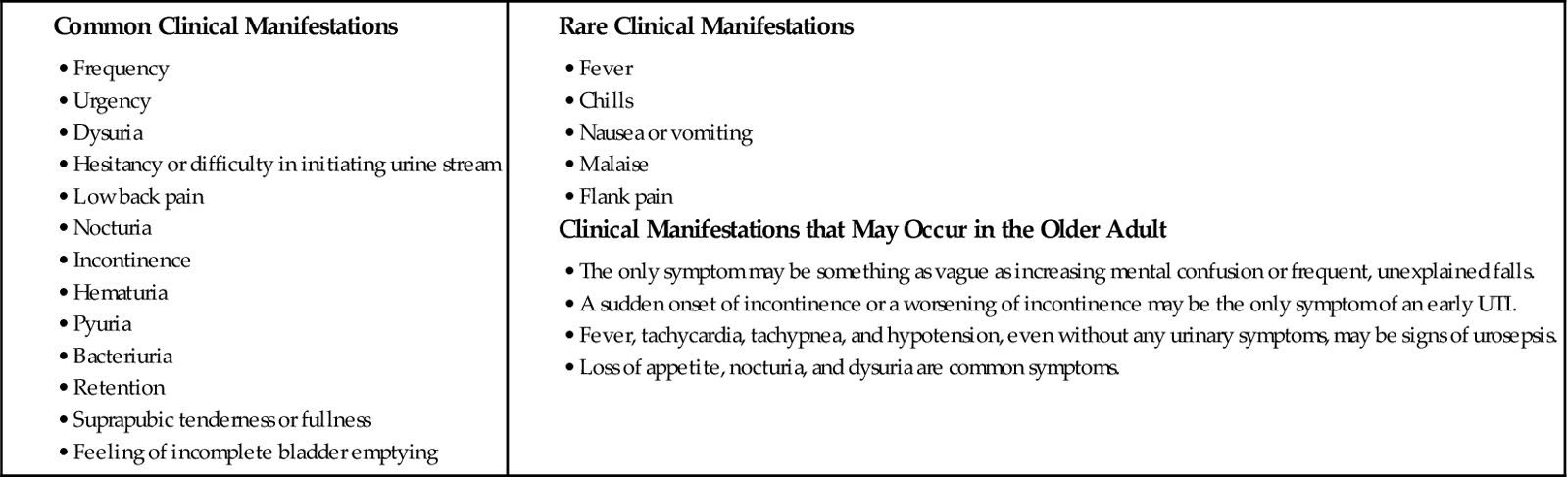

Frequency, urgency, and dysuria are the common manifestations of a urinary tract infection (UTI), but other manifestations may be present (Chart 69-3). Urine may be cloudy, foul smelling, or blood tinged. Ask the patient about risk factors for UTI during the assessment (see Table 69-1). For noninfectious cystitis, the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency (PUF) Patient Symptom Scale can identify patients with interstitial cystitis.

Before performing the physical assessment, ask the patient to void so that the urine can be examined and the bladder emptied before palpation. Assess vital signs to help rule out sepsis. Inspect the lower abdomen, and palpate the urinary bladder. Distention after voiding indicates incomplete bladder emptying.

Using Standard Precautions, examine any lesions around the urethral meatus and vaginal opening. To help differentiate between a vaginal and a urinary tract infection, note whether there is any vaginal discharge (vaginal discharge and irritation are more indicative of vaginal infection). Women often report burning with urination when normal acidic urine touches labial tissues that are inflamed or ulcerated by vaginal infections or sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Maintain privacy with drapes during the examination.

The prostate is palpated by digital rectal examination (DRE) for size, change in shape or consistency, and tenderness. The physician or advanced practice nurse performs the DRE.

Laboratory Assessment

Laboratory assessment for a UTI is a urinalysis with testing for leukocyte esterase and nitrate. The combination of a positive leukocyte esterase and nitrate is 68% to 88% sensitive in the diagnosis of a UTI (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007). Although a urinalysis can include a microscopic count of bacteria, white blood cells (WBCs), and red blood cells (RBCs), this additional testing is more expensive, is time consuming, and may not improve diagnostic accuracy. The presence of more than 20 epithelial cells/high power field (hpf) suggests contamination. The presence of 100,000 colonies/mL or the presence of three or more WBCs (pyuria) with RBCs (hematuria) indicates infection.

A urinalysis is performed on a clean-catch midstream specimen. If the patient cannot produce a clean-catch specimen, you may need to obtain the specimen with a small-diameter (6 Fr) catheter. For a routine urinalysis, 10 mL of urine is needed; smaller quantities are sufficient for culture.

A urine culture confirms the type of organism and the number of colonies. Urine culture is expensive, and results take at least 48 hours. It is indicated when the UTI is complicated or does not respond to usual therapy or the diagnosis is uncertain. A UTI is confirmed when more than 105 colony-forming units are in the urine from any patient. In patients who also have symptoms of UTI, as few as 103 colony-forming units may allow the diagnosis to be made. The presence of many different types of organisms in low colony counts usually indicates that the specimen is contaminated. Sensitivity testing follows culture results when complicating factors are present (e.g., stones or recurrent infection), when the patient is older, or to ensure the appropriate antibiotics are prescribed.

Occasionally the serum WBC count may be elevated, with the differential WBC count showing a “left shift” (see Chapter 19). This shift indicates that the number of immature WBCs is increasing in response to the infection. As a result, the number of bands, or immature WBCs, is elevated. Left shift most often occurs with urosepsis and rarely occurs with uncomplicated cystitis, which is a local rather than a systemic infection.

Other Diagnostic Assessment

The diagnosis of cystitis is based on the history, physical examination, and laboratory data. If urinary retention and obstruction of urine outflow are suspected, urography, abdominal sonography, or computed tomography (CT) may be needed to locate the site of obstruction or the presence of calculi. Voiding cystourethrography (see Chapter 68) is needed when ureteral reflux is suspected.

Cystoscopy (see Chapter 68) may be performed when the patient has recurrent UTIs (more than three or four a year). A urine culture is performed first to ensure that no infection is present. If infection is present, the urine is sterilized with antibiotic therapy before the procedure to reduce the risk for sepsis. Cystoscopy identifies abnormalities that increase the risk for cystitis. Such abnormalities include bladder calculi, bladder diverticula, urethral strictures, foreign bodies (e.g., sutures from previous surgery), and trabeculation (an abnormal thickening of the bladder wall caused by urinary retention and obstruction). Retrograde pyelography, along with the cystoscopic examination, shows outlines and images of the drainage tract. Areas of obstruction or malformation and the presence of reflux are then identified early.

Cystoscopy is needed to accurately diagnose interstitial cystitis. A urinalysis usually shows WBCs and RBCs but no bacteria. Common findings in interstitial cystitis are a small-capacity bladder, the presence of Hunner’s ulcers (a type of bladder lesion), and small hemorrhages after bladder distention.

Interventions

Nonsurgical Management

The expected outcome is to maintain an optimal urinary elimination pattern. Nursing interventions for the management of cystitis focus on comfort and teaching about drug therapy, nutrition therapy, and prevention measures.

Drug Therapy.

Drugs used to treat bacteriuria and promote patient comfort include urinary antiseptics or antibiotics, analgesics, and antispasmodics. Cure of a UTI depends on the antibiotic levels achieved in the urine (Chart 69-4). Oral antifungal agents are usually prescribed for fungal infections. When oral antifungal therapy is not sufficient, amphotericin B is most often given in daily bladder instillations. Antispasmodic drugs decrease bladder spasm and promote complete bladder emptying.

Antibiotic therapy is used for bacterial UTIs (see Chart 69-4). Guidelines indicate that a 3-day, high-dose course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or a fluoroquinolone is effective in treating uncomplicated, community-acquired UTIs in women (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007). Fluoroquinolones cannot be used to treat UTIs during pregnancy because of the potential for birth defects. The shorter courses increase adherence and reduce cost. Longer antibiotic treatment (7 to 21 days) and/or different agents are required for hospitalized patients; those with complicating factors, such as pregnancy, indwelling catheters, or stones; and those with diabetes or immunosuppression.

Long-term, low-dose antibiotic therapy is used for chronic, recurring infections caused by structural abnormalities or stones. Trimethoprim 100 mg daily may be used for long-term management of the older patient with frequent UTIs. For women who have recurrent UTIs after intercourse, one low-dose tablet of trimethoprim (TMP) (Proloprim, Trimpex) or TMP/sulfamethoxazole (half or single-strength Bactrim, Cotrim, Septra) or nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin, Nephronex ![]() , Novofuran

, Novofuran ![]() ) after intercourse is often prescribed. Estrogen used as an intravaginal cream may prevent recurrent UTIs in the postmenopausal woman, although this therapy is controversial.

) after intercourse is often prescribed. Estrogen used as an intravaginal cream may prevent recurrent UTIs in the postmenopausal woman, although this therapy is controversial.

Nutrition Therapy.

The diet should include all food groups and include more calories for the increased metabolism caused by infection. Urge patients to drink enough fluid to maintain a diluted urine throughout the day and night unless fluid restriction is required for other health problems. The drinking of 50 mL of concentrated cranberry juice daily appears to decrease the ability of bacteria to adhere to the epithelial cells lining the urinary tract, decreasing the incidence of symptomatic UTIs in some patients. Cranberry juice must be consumed for 3 to 4 weeks to be effective, and the efficacy of cranberry tablets has not been established (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007). It is important to note that cranberry juice is an irritant to the bladder with interstitial cystitis and should be avoided by patients with this condition. Avoiding caffeine, carbonated beverages, and tomato products may decrease bladder irritation during cystitis.

Comfort Measures.

A warm sitz bath taken two or three times a day for 20 minutes may provide comfort and some relief of local symptoms. If burning with urination is severe or urinary retention occurs, teach the patient to sit in the sitz bath and urinate into the warm water.

Surgical Management

Surgery for cystitis treats the conditions that increase the risk for recurrent UTIs (e.g., removal of obstructions and repair of vesicoureteral reflux). Procedures may include cystoscopy (see Chapter 68) to identify and remove calculi or obstructions.

Community-Based Care

Assess the patient’s level of understanding of the problem. His or her knowledge about factors that promote the development of cystitis determines the teaching interventions planned.

Teach the patient how to take prescribed drugs. Stress the need for correct spacing of doses throughout the day and the need to complete all of the prescribed drugs. If the drug will change the color of the urine, as it does with phenazopyridine (Pyridium, Urogesic, Phenazo ![]() ), inform the patient to expect this change. Offer techniques for remembering the drug schedule, such as the use of a daily calendar or the association of drugs with usual activities (e.g., mealtimes).

), inform the patient to expect this change. Offer techniques for remembering the drug schedule, such as the use of a daily calendar or the association of drugs with usual activities (e.g., mealtimes).

Patients may associate symptoms of discomfort with sexual activities and have feelings of guilt and embarrassment. Open and sensitive discussions with a woman who has recurrences of UTI after sexual intercourse can help her find techniques to handle the problem (see Chart 69-2). Explore with her the factors that contribute to her infections, such as sexual penetration when the bladder is full, diaphragm use, and her general resistance to infection. Some positions during intercourse may reduce urethral irritation and subsequent cystitis. Remind the patient that although perineal washing before intercourse is helpful, vigorous cleaning of the perineum with harsh soaps and vaginal douching may irritate the perineal tissues and increase the risk for UTI. At the patient’s request, discuss the problem with her and her partner to help them find ways of maintaining their intimate relationship.

Urethritis

Pathophysiology

Urethritis is an inflammation of the urethra that causes symptoms similar to urinary tract infection (UTI). In men, manifestations include burning or difficulty urinating and a discharge from the urethral meatus. The most common cause of urethritis in men is sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). These include gonorrhea or nonspecific urethritis caused by Ureaplasma (a gram-negative bacterium), Chlamydia (a sexually transmitted gram-negative bacterium), or Trichomonas vaginalis (a protozoan found in both the male and female genital tract).

In women, urethritis causes manifestations similar to those of bacterial cystitis. Urethritis is known by several other terms: pyuria-dysuria syndrome, frequency-dysuria syndrome, trigonitis syndrome, and urethral syndrome. Urethritis is most common in postmenopausal women and appears to be caused by tissue changes related to low estrogen levels.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Ask the patient about a history of STD, painful or difficult urination, discharge from the penis or vagina, and discomfort in the lower abdomen. Urinalysis may show pyuria (white blood cells [WBCs] in the urine) without a large number of bacteria. However, results of urethral culture may indicate an STD. In women, the diagnosis may be made by excluding cystitis when urinalysis and urethral culture are negative for bacteria but symptoms persist. In such cases, pelvic examination may reveal tissue changes from low estrogen levels in the vagina. Urethroscopy may show low estrogen changes with inflammation of urethral tissues.

STDs and infection are treated with antibiotic therapy. More information on STDs can be found in Chapter 76.

Postmenopausal women often have improvement in their urethral symptoms with the use of estrogen vaginal cream. Estrogen cream applied locally to the vagina increases the amount of estrogen in the urethra as well, and irritating symptoms are reduced.

Noninfectious Disorders

Urethral Strictures

Urethral strictures are narrowed areas of the urethra. These problems may be caused by complications of an STD (usually gonorrhea) and by trauma during catheterization, urologic procedures, or childbirth. About one third of urethral strictures have no obvious cause. Strictures occur more often in men than in women. They may be a factor in other urologic problems, such as recurrent UTIs, urinary incontinence, and urinary retention.

The most common symptom of urethral stricture is obstruction of urine flow. Strictures rarely cause pain. Because urine stasis can result when flow is obstructed, the patient with a stricture is at risk for developing a UTI and may have overflow incontinence. Overflow incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine when the bladder is overdistended. Assess the patient for these two problems.

A urethral stricture is treated surgically. Dilation of the urethra (using a local anesthetic) is only a temporary measure, not a curative one. Stent placement can be used in some patients. The best chance of long-term cure is with urethroplasty, which is the surgical removal of the affected area with or without grafting to create a larger opening. The recurrence rate after surgery is still high, and most patients need repeated procedures. The urethral stricture location and length are the most important factors affecting choice of interventions and recovery.

Urinary Incontinence

Pathophysiology

Continence is the control over the time and place of urination and is unique to humans and some domestic animals. It is a learned behavior in which a person can suppress the urge to urinate until a socially appropriate location is available (e.g., a toilet). Efficient bladder emptying (i.e., coordination between bladder contraction and urethral relaxation) is needed for continence.

Incontinence is an involuntary loss of urine severe enough to cause social or hygienic problems. It is not a normal consequence of aging or childbirth and often is a stigmatizing and an underreported health problem. Many people suffer in silence, are socially isolated, and may be unaware that treatment is available. In addition, the cost of incontinence can be enormous.

Continence occurs when pressure in the urethra is greater than pressure in the bladder. For normal voiding to occur, the urethra must relax and the bladder must contract with enough pressure and duration to empty completely. Voiding should occur in a smooth and coordinated manner under a person’s conscious control. Incontinence has several possible causes and can be either temporary or chronic (Table 69-3). Temporary causes usually do not involve a disorder of the urinary tract. The most common forms of adult urinary incontinence are stress incontinence, urge incontinence, overflow incontinence, functional incontinence, and a mixed form.

TABLE 69-3

cup of cold water, stir well, and drink all the liquid.

cup of cold water, stir well, and drink all the liquid.