Donna D. Ignatavicius

Care of Patients with Stomach Disorders

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

6 Compare etiologies and assessment findings of acute and chronic gastritis.

7 Identify risk factors for gastritis.

8 Compare and contrast assessment findings associated with gastric and duodenal ulcers.

9 Identify the most common medical complications that can result from PUD.

10 Describe the purpose and adverse effects of drug therapy for gastritis and PUD.

11 Monitor patients with PUD and gastric cancer for signs of upper GI bleeding.

12 Prioritize interventions for patients with upper GI bleeding.

13 Plan individualized care for the patient having gastric surgery.

14 Explain the purpose and procedure for gastric lavage.

15 Evaluate the impact of gastric disorders on the nutrition status of the patient.

16 Develop a preoperative and postoperative plan of care for the patient undergoing gastric surgery.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Bleeding Ulcer, Pathophysiology

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

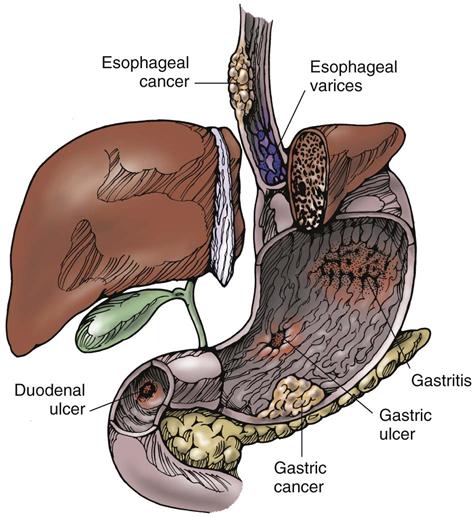

Although only a few diseases affect the stomach, they can be very serious and in some cases life threatening. The most common disorders include gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer. Each of these health problems can result in impaired or altered digestion and nutrition. The stomach is part of the upper GI system that is responsible for a large part of the digestive process. Patient-centered collaborative care for stomach disorders often includes therapies to meet the patient’s need for adequate nutrition.

Gastritis

Gastritis is the inflammation of gastric mucosa (stomach lining). It can be scattered or localized and can be classified according to cause, cellular changes, or distribution of the lesions. Gastritis can be erosive (causing ulcers) or nonerosive. Although the mucosal changes that result from acute gastritis typically heal after several months, this is not true for chronic gastritis.

Pathophysiology

Prostaglandins provide a protective mucosal barrier that prevents the stomach from digesting itself by a process called acid autodigestion. If there is a break in the protective barrier, mucosal injury occurs. The resulting injury is worsened by histamine release and vagus nerve stimulation. Hydrochloric acid can then diffuse back into the mucosa and injure small vessels. This back-diffusion causes edema, hemorrhage, and erosion of the stomach’s lining. The pathologic changes of gastritis include vascular congestion, edema, acute inflammatory cell infiltration, and degenerative changes in the superficial epithelium of the stomach lining.

Types of Gastritis

Inflammation of the gastric mucosa or submucosa after exposure to local irritants or other cause can result in acute gastritis. The early pathologic manifestation of gastritis is a thickened, reddened mucous membrane with prominent rugae, or folds. Various degrees of mucosal necrosis and inflammatory reaction occur in acute disease. The diagnosis cannot be based solely on clinical symptoms. Complete regeneration and healing usually occur within a few days. If the stomach muscle is not involved, complete recovery usually occurs with no residual evidence of gastric inflammatory reaction. If the muscle is affected, hemorrhage may occur during an episode of acute gastritis.

Chronic gastritis appears as a patchy, diffuse (spread out) inflammation of the mucosal lining of the stomach. As the disease progresses, the walls and lining of the stomach thin and atrophy. With progressive gastric atrophy from chronic mucosal injury, the function of the parietal (acid-secreting) cells decreases and the source of intrinsic factor is lost. The intrinsic factor is critical for absorption of vitamin B12. When body stores of vitamin B12 are eventually depleted, pernicious anemia results. The amount and concentration of acid in stomach secretions gradually decrease until the secretions consist of only mucus and water.

Chronic gastritis is associated with an increased risk for gastric cancer. The persistent inflammation extends deep into the mucosa, causing destruction of the gastric glands and cellular changes. Chronic gastritis may be categorized as type A, type B, or atrophic.

Type A (nonerosive) chronic gastritis refers to an inflammation of the glands, as well as the fundus and body of the stomach. Type B chronic gastritis usually affects the glands of the antrum but may involve the entire stomach. In atrophic chronic gastritis, diffuse inflammation and destruction of deeply located glands accompany the condition. Chronic atrophic gastritis affects all layers of the stomach, thus decreasing the number of cells. The muscle thickens, and inflammation is present. Chronic atrophic gastritis is characterized by total loss of fundal glands, minimal inflammation, thinning of the gastric mucosa, and intestinal metaplasia (abnormal tissue development). These cellular changes can lead to peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and gastric cancer (McCance et al., 2010).

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Acute Gastritis.

The onset of infection with Helicobacter pylori can result in acute gastritis. H. pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that penetrates the mucosal gel layer of the gastric epithelium. Although less common, other forms of bacterial gastritis from organisms such as staphylococci, streptococci, Escherichia coli, or salmonella can cause life-threatening problems such as sepsis and extensive tissue necrosis (death).

Long-term NSAID use creates a high risk for acute gastritis. NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin production in the mucosal barrier. Other risk factors include alcohol, caffeine, and corticosteroids. Acute gastritis is also caused by local irritation from radiation therapy and accidental or intentional ingestion of corrosive substances, including acids or alkalis (e.g., lye and drain cleaners). Emotional stress and acute anxiety may also contribute to gastritis.

Chronic Gastritis.

Type A gastritis has been associated with the presence of antibodies to parietal cells and intrinsic factor. Therefore an autoimmune cause for this type of gastritis is likely. Parietal cell antibodies have been found in most patients with pernicious anemia and in more than one half of those with type A gastritis. A genetic link to this disease, with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, has been found in the relatives of patients with pernicious anemia (McCance et al., 2010).

The most common form of the disease is type B gastritis, caused by H. pylori infection. A direct correlation exists between the number of organisms and the degree of cellular abnormality present. The host response to the H. pylori infection is activation of lymphocytes and neutrophils. Release of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha, damages the gastric mucosa (McCance et al., 2010).

Chronic local irritation and toxic effects caused by alcohol ingestion, radiation therapy, and smoking have been linked to chronic gastritis. Surgical procedures that involve the pyloric sphincter, such as a pyloroplasty, can lead to gastritis by causing reflux of alkaline secretions into the stomach. Other systemic disorders such as Crohn’s disease, graft-versus-host disease, and uremia can also precipitate the development of chronic gastritis.

Atrophic gastritis is a type of chronic gastritis that is seen most often in older adults. It can occur after exposure to toxic substances in the workplace (e.g., benzene, lead, nickel) or H. pylori infection, or it can be related to autoimmune factors.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Gastritis is a very common health problem in the United States. Yet, a balanced diet, regular exercise, and stress-reduction techniques can help prevent it (Chart 58-1). A balanced diet includes following the recommendations of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and limiting intake of foods and spices that can cause gastric distress, such as caffeine, chocolate, mustard, pepper, and other strong or hot spices. Alcohol and tobacco consumption should also be avoided. Regular exercise maintains peristalsis, which helps prevent gastric contents from irritating the gastric mucosa. Stress-reduction techniques can include aerobic exercise, meditation, reading, and/or yoga, depending on individual preferences. Psychotherapy may also be considered.

Excessive use of aspirin and other NSAIDs should also be avoided. If a family member has H. pylori infection or has had it in the past, patient testing should be considered. This test can identify the bacteria before they cause gastritis.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

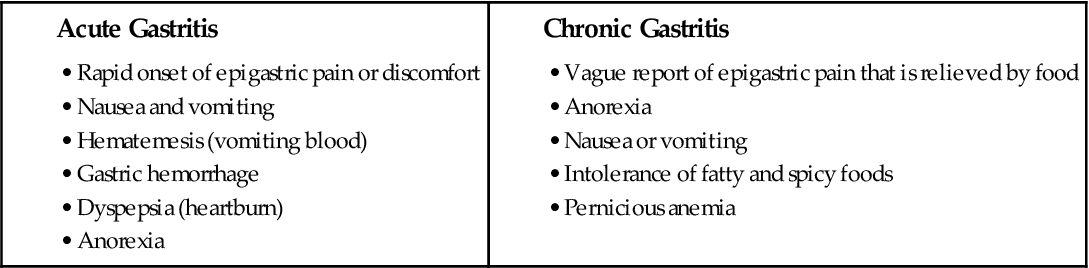

Symptoms of acute gastritis range from mild to severe. The patient may report epigastric discomfort, anorexia, cramping, nausea, and vomiting (Chart 58-2). Assess for abdominal tenderness and bloating, hematemesis (vomiting blood), or melena (traces of blood in the stool). Symptoms last only a few hours or days and vary with the cause. Aspirin/NSAID–related gastritis may result in dyspepsia (heartburn). Gastritis or food poisoning caused by endotoxins, such as staphylococcal endotoxin, has an abrupt onset. Severe nausea and vomiting often occur within 5 hours of ingestion of the contaminated food. In some cases, gastric hemorrhage is the presenting symptom, which is a life-threatening emergency.

Chronic gastritis causes few symptoms unless ulceration occurs. Patients may report nausea, vomiting, or upper abdominal discomfort. Periodic epigastric pain may occur after a meal. Some patients have anorexia (see Chart 58-2).

Several blood tests are available to detect H. pylori if gastritis or an ulcer is suspected. Examples of these tests are described on p. 1228 in the Peptic Ulcer Disease section of this chapter. One of the most common methods is a blood test to detect IgG or IgM anti–H. pylori antibodies.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) via an endoscope with biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing gastritis. The physician takes a biopsy to establish a definitive diagnosis of the type of gastritis. If lesions are patchy and diffuse, biopsy of several suspicious areas may be necessary to avoid misdiagnosis. A cytologic examination of the biopsy specimen is performed to confirm or rule out gastric cancer. Tissue samples can also be taken to detect H. pylori using rapid urease testing. As the name implies, this test provides quick results unlike the more traditional tissue culture that takes several weeks to determine if the bacteria are present. The results of these tests are more reliable if the patient has discontinued taking antacids for at least a week (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

Interventions

Patients with gastritis are not often seen in the acute care setting unless they have an exacerbation (“flare up”) of acute or chronic gastritis that results in fluid and electrolyte imbalance or bleeding. Collaborative care is directed toward supportive care for relieving the symptoms and removing or reducing the cause of discomfort.

Acute gastritis is treated symptomatically and supportively because the healing process is spontaneous, usually occurring within a few days. When the cause is removed, pain and discomfort usually subside. If bleeding is severe, a blood transfusion may be necessary. Fluid replacement is prescribed for patients with severe fluid loss. Surgery, such as partial gastrectomy, pyloroplasty, and/or vagotomy, may be needed for patients with major bleeding or ulceration. Treatment of chronic gastritis varies with the cause. The approach to management includes the elimination of causative agents, treatment of any underlying disease (e.g., uremia, Crohn’s disease), avoidance of toxic substances (e.g., alcohol, tobacco), and health teaching.

Eliminating the causative factors, such as H. pylori infection if present, is the primary treatment approach. Drugs and nutritional therapy are also used. In the acute phase, the health care provider prescribes drugs that block and buffer gastric acid secretions to relieve pain.

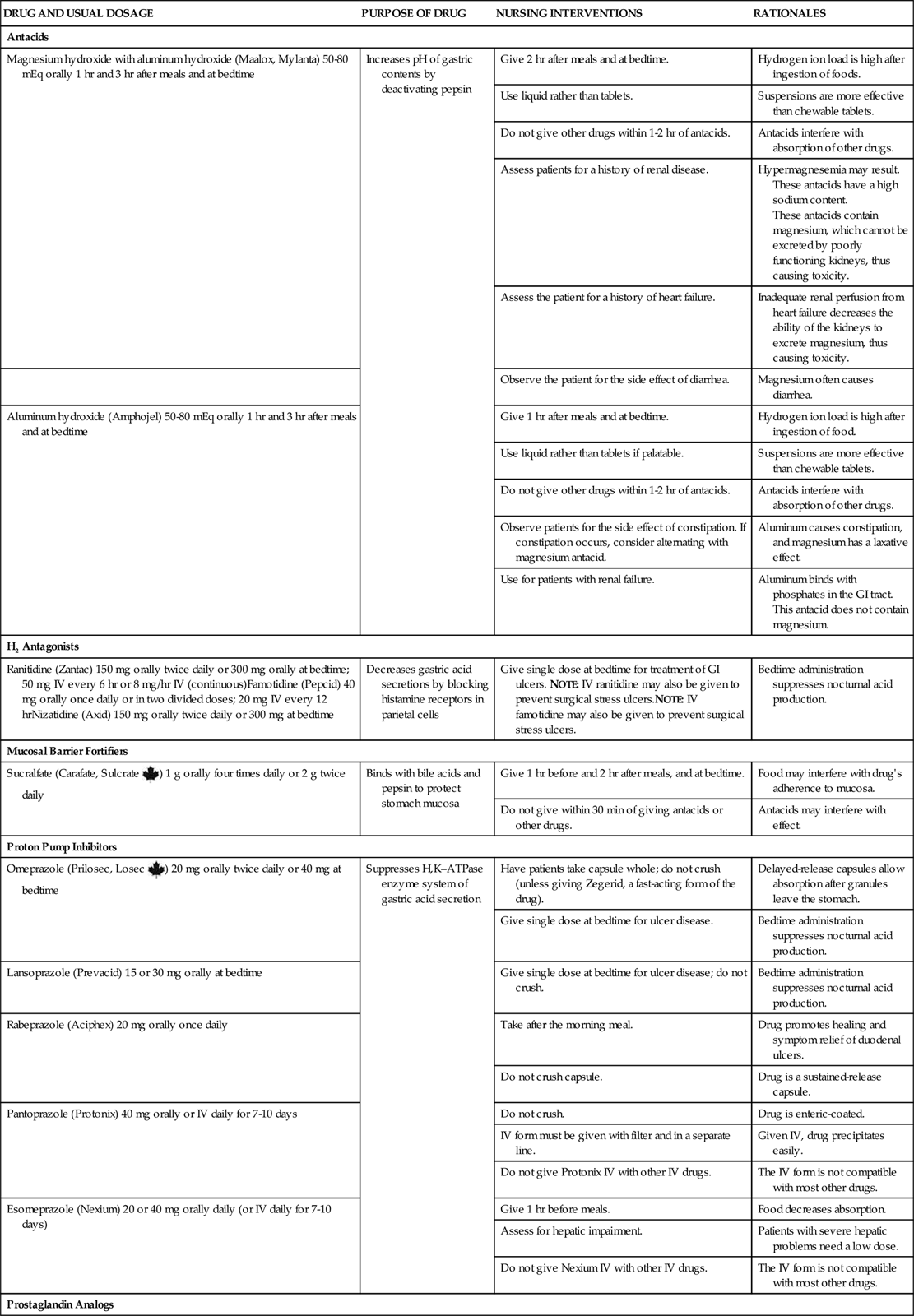

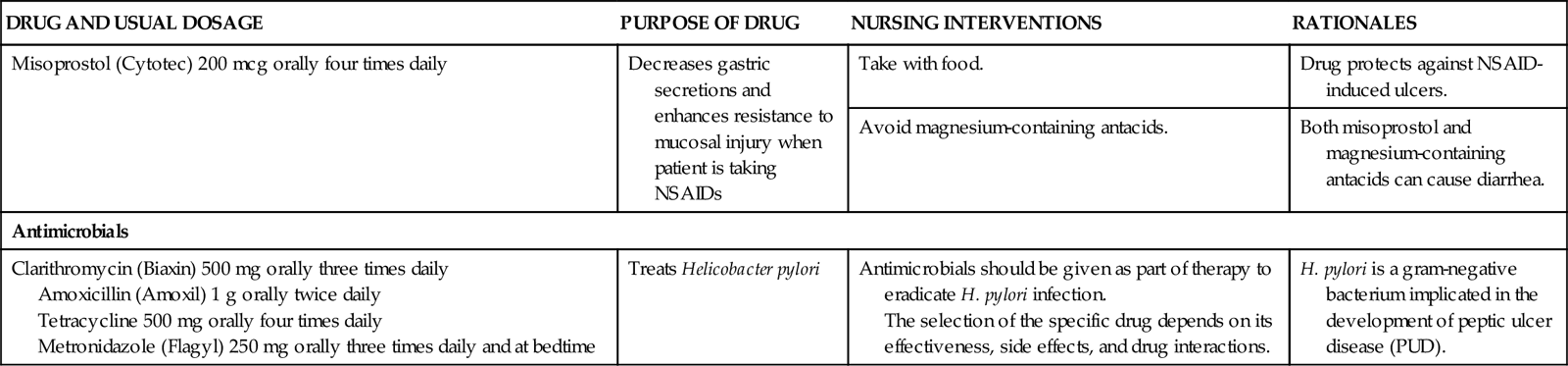

H2-receptor antagonists, such as famotidine (Pepcid) and nizatidine (Axid), are typically used to block gastric secretions. Sucralfate (Carafate, Sulcrate ![]() ), a mucosal barrier fortifier, may also be prescribed. Antacids used as buffering agents include aluminum hydroxide combined with magnesium hydroxide (Maalox) and aluminum hydroxide combined with simethicone and magnesium hydroxide (Mylanta). Antisecretory agents (proton pump inhibitors [PPIs]) such as omeprazole (Prilosec) or pantoprazole (Protonix) may be prescribed to suppress gastric acid secretion (Chart 58-3).

), a mucosal barrier fortifier, may also be prescribed. Antacids used as buffering agents include aluminum hydroxide combined with magnesium hydroxide (Maalox) and aluminum hydroxide combined with simethicone and magnesium hydroxide (Mylanta). Antisecretory agents (proton pump inhibitors [PPIs]) such as omeprazole (Prilosec) or pantoprazole (Protonix) may be prescribed to suppress gastric acid secretion (Chart 58-3).

Patients with chronic gastritis may require vitamin B12 for prevention or treatment of pernicious anemia. If H. pylori is found, the health care provider treats the infection. Current practice for infection treatment is described on p. 1229 in the discussion of Drug Therapy in the Peptic Ulcer Disease section.

The nurse, health care provider, or pharmacist teaches patients to avoid drugs and other irritants that are associated with gastritis episodes, if possible. These drugs include corticosteroids, erythromycin (E-Mycin, Erythromid ![]() ), and NSAIDs, such as naproxen (Naprosyn) and ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, Amersol

), and NSAIDs, such as naproxen (Naprosyn) and ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, Amersol ![]() , Novo-Profen

, Novo-Profen ![]() ). NSAIDs are also available as OTC drugs and should not be used. Teach patients to read all OTC drug labels because many preparations contain aspirin or other NSAID.

). NSAIDs are also available as OTC drugs and should not be used. Teach patients to read all OTC drug labels because many preparations contain aspirin or other NSAID.

Instruct the patient to limit intake of any foods and spices that cause distress, such as those that contain caffeine or high acid content (e.g., tomato products, citrus juices) or those that are heavily seasoned with strong or hot spices. Bell peppers and onions are also commonly irritating foods. Most patients seem to progress better with a bland, non-spicy diet and smaller, more frequent meals. Alcohol and tobacco should also be avoided.

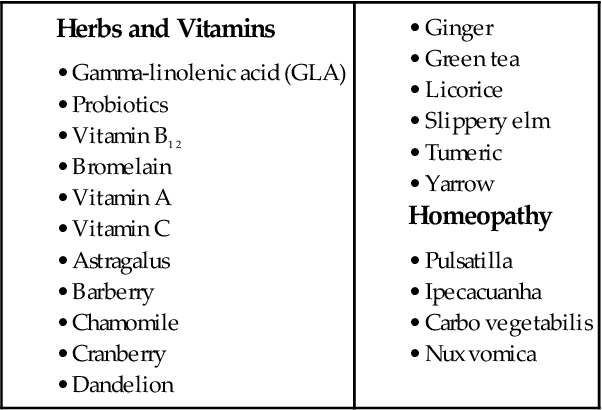

Assist the patient with various techniques that reduce stress and discomfort, such as progressive relaxation, cutaneous stimulation, guided imagery, and distraction. Other complementary and alternative therapies that have been used are listed in Table 58-1. Chapter 2 describes these therapies in detail.

Peptic Ulcer Disease

A peptic ulcer is a mucosal lesion of the stomach or duodenum. Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) results when mucosal defenses become impaired and no longer protect the epithelium from the effects of acid and pepsin.

Pathophysiology

Types of Ulcers

Three types of ulcers may occur: gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and stress ulcers (less common). Most gastric and duodenal ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection, which is transmitted via the fecal-oral route and thought to be acquired in childhood. It can also be transmitted from contaminated endoscopic equipment (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). About half of the world’s population is infected with the bacterium (Fromm, 2009).

As a response to the bacteria, cytokines, neutrophils, and other substances are activated and cause epithelial cell necrosis. Urease, a substance secreted by the H. pylori bacterium, produces ammonia and creates a more alkaline environment (McCance et al., 2010). Hydrogen ions are then released in response to the presence of ammonia and contribute further to mucosal damage. Urease can be detected through laboratory testing to confirm the H. pylori infection.

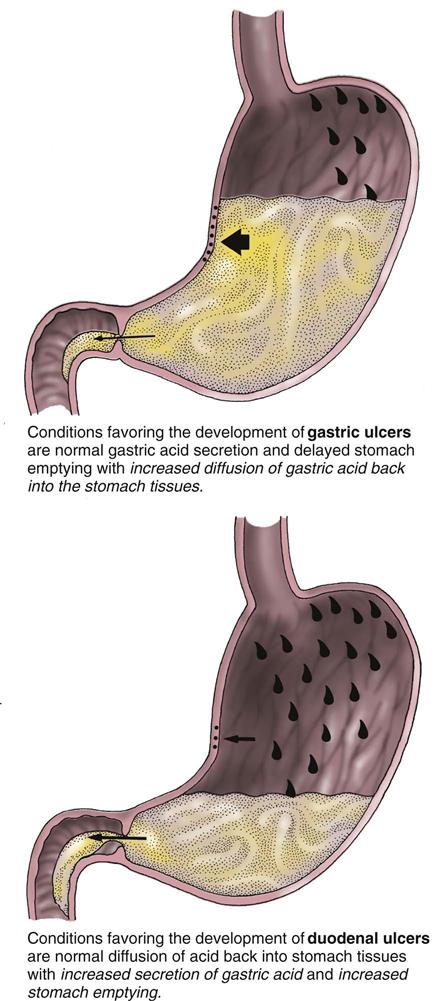

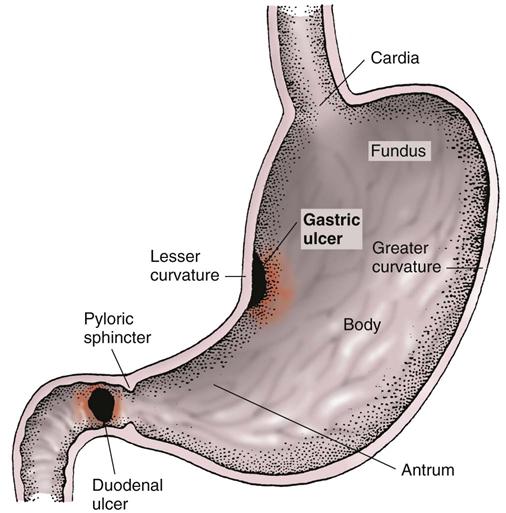

Gastric ulcers usually develop in the antrum of the stomach near acid-secreting mucosa. When a break in the mucosal barrier occurs (such as that caused by H. pylori infection), hydrochloric acid injures the epithelium. Gastric ulcers may then result from back-diffusion of acid or dysfunction of the pyloric sphincter (Fig. 58-1). Without normal functioning of the pyloric sphincter, bile refluxes (backs up) into the stomach. This reflux of bile acids may break the integrity of the mucosal barrier and produce hydrogen ion back-diffusion, which leads to mucosal inflammation. Toxic agents and bile then destroy the membrane of the gastric mucosa.

Gastric emptying is often delayed in patients with gastric ulceration. This causes regurgitation of duodenal contents, which worsens the gastric mucosal injury. Decreased blood flow to the gastric mucosa may also alter the defense barrier and thereby allow ulceration to occur. Gastric ulcers are deep and penetrating, and they usually occur on the lesser curvature of the stomach, near the pylorus (Fig. 58-2).

Most duodenal ulcers occur in the upper portion of the duodenum. They are deep, sharply demarcated lesions that penetrate through the mucosa and submucosa into the muscularis propria (muscle layer). The floor of the ulcer consists of a necrotic area residing on granulation tissue and surrounded by areas of fibrosis.

The main feature of a duodenal ulcer is high gastric acid secretion, although a wide range of secretory levels is found. In patients with duodenal ulcers, pH levels are low (excess acid) in the duodenum for long periods. Protein-rich meals, calcium, and vagus nerve excitation stimulate acid secretion. Combined with hypersecretion, a rapid emptying of food from the stomach reduces the buffering effect of food and delivers a large acid bolus to the duodenum (see Fig. 58-1). Inhibitory secretory mechanisms and pancreatic secretion may be insufficient to control the acid load.

Many patients with duodenal ulcer disease have confirmed H. pylori infection. These bacteria produce substances that damage the mucosa. Urease produced by H. pylori breaks down urea into ammonia.

Stress ulcers are acute gastric mucosal lesions occurring after an acute medical crisis or trauma, such as head injury and sepsis. In the patient who is NPO for major surgery, gastritis may lead to stress ulcers, which are multiple shallow erosions of the stomach and occasionally the proximal duodenum. Patients who are critically ill, especially those with extensive burns (Curling’s ulcer), sepsis (ischemic ulcer), or increased intracranial pressure (Cushing’s ulcer), are also susceptible to these ulcers.

Bleeding caused by gastric erosion is the main manifestation of acute stress ulcers. Multifocal lesions associated with stress ulcers occur in the stomach and proximal duodenum. These lesions begin as areas of ischemia and evolve into erosions and ulcerations that may progress to massive hemorrhage. Little is known of the exact etiology of stress ulcers. However, in the presence of elevated levels of hydrochloric acid, ischemic areas can progress to erosive gastritis and subsequent ulcerations. Stress ulcers are associated with lengthened hospital stay and increased mortality rates.

Complications of Ulcers

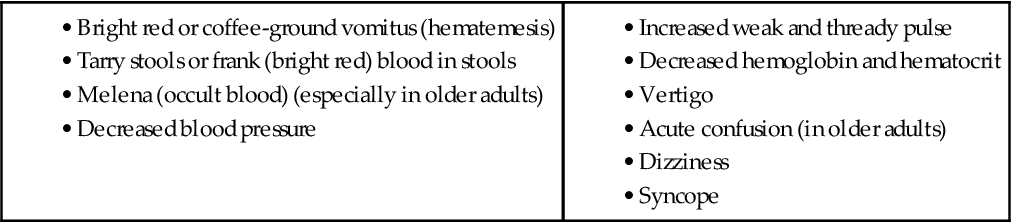

The most common complications of PUD are hemorrhage, perforation, pyloric obstruction, and intractable disease. Hemorrhage is the most serious complication (Fig. 58-3). It tends to occur more often in patients with gastric ulcers and in older adults. Many patients have a second episode of bleeding if underlying infection with H. pylori remains untreated or if therapy does not include an H2 antagonist. With massive bleeding, the patient vomits bright red or coffee-ground blood (hematemesis). Hematemesis usually indicates bleeding at or above the duodenojejunal junction (upper GI bleeding) (Chart 58-4).

Minimal bleeding from ulcers is manifested by occult blood in a tarry stool (melena). Melena may occur in patients with gastric ulcers but is more common in those with duodenal ulcers. Gastric acid digestion of blood typically results in a granular dark vomitus (coffee-ground appearance). The digestion of blood within the duodenum and small intestine may result in a black stool.

Gastric and duodenal ulcers can perforate and bleed. Perforation occurs when the ulcer becomes so deep that the entire thickness of the stomach or duodenum is worn away. The stomach or duodenal contents can then leak into the peritoneal cavity. Sudden, sharp pain begins in the midepigastric region and spreads over the entire abdomen. The amount of pain correlates with the amount and type of GI contents spilled. The classic pain causes the patient to be apprehensive. The abdomen is tender, rigid, and boardlike (peritonitis). The patient assumes the knee-chest (“fetal”) position to decrease the tension on the abdominal muscles. He or she can become severely ill within hours. Bacterial septicemia and hypovolemic shock follow. Peristalsis diminishes, and paralytic ileus develops. Peptic ulcer perforation is a surgical emergency and can be life threatening!

Pyloric (gastric outlet) obstruction (blockage) occurs in a small percentage of patients and is manifested by vomiting caused by stasis and gastric dilation. Obstruction occurs at the pylorus (the gastric outlet) and is caused by scarring, edema, inflammation, or a combination of these factors.

Symptoms of obstruction include abdominal bloating, nausea, and vomiting. When vomiting persists, the patient may have hypochloremic (metabolic) alkalosis from loss of large quantities of acid gastric juice (hydrogen and chloride ions) in the vomitus. Hypokalemia may also result from the vomiting or metabolic alkalosis.

Many patients with ulcers have a single episode with no recurrence. However, intractability may develop from complications of ulcers, excessive stressors in the patient’s life, or an inability to adhere to long-term therapy. He or she no longer responds to conservative management, or recurrences of symptoms interfere with ADLs. In general, the patient continues to have recurrent pain and discomfort despite treatment. Those who fail to respond to traditional treatments or who have a relapse after discontinuation of therapy are referred to a gastroenterologist.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Peptic ulcer development is associated primarily with bacterial infection with H. pylori and NSAIDs. NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen) break down the mucosal barrier and disrupt the mucosal protection mediated systemically by cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition. COX-2 inhibitors (celecoxib [Celebrex]) are less likely to cause mucosal damage but place patients at high risk for cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction. In addition, NSAIDs cause decreased endogenous prostaglandins, resulting in local gastric mucosal injury. GI complications from NSAID use can occur at any time, even after long-term uncomplicated use. NSAID-related ulcers are difficult to treat, even with long-term therapy, because these ulcers have a high rate of recurrence.

Certain substances may contribute to gastroduodenal ulceration by altering gastric secretion, producing localized damage to mucosa and interfering with the healing process. For example, corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), theophylline (Theo-Dur), and caffeine stimulate hydrochloric acid production. Patients receiving radiation therapy may also develop GI ulcers. Other risk factors for PUD are the same as for gastritis (see Chart 58-1).

Genetic factors may be important. H. pylori infection tends to occur in people who are genetically susceptible. Those with a family history of PUD are at higher risk for having PUD than those without a family history (McCance et al., 2010).

Incidence/Prevalence

PUD affects millions of people across the world. However, health care provider visits, hospitalizations, and the mortality rate for PUD have decreased in the past few decades. The use of proton pump inhibitors and H. pylori treatment may explain these declines. Duodenal ulcers are increasing in “baby boomers,” however, which may be the result of increased NSAID use for arthritic pain as they age.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Health promotion and illness prevention practices are the same as for gastritis (see Chart 58-1). For critically ill patients, health care providers prescribe drug therapy to prevent stress ulcers as described on p. 1229 in the Drug Therapy section.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Collect data related to the causes and risk factors for peptic ulcer disease (PUD). Question the patient about factors that can influence the development of PUD, including alcohol intake and tobacco use. Note if certain foods such as tomatoes or caffeinated beverages precipitate or worsen symptoms. Information regarding actual or perceived daily stressors should also be obtained.

A history of current or past medical conditions focuses on GI problems, particularly any history of diagnosis or treatment for H. pylori infection. Review all prescription and OTC drugs that the patient is taking. Specifically inquire whether the patient is taking corticosteroids, chemotherapy, or NSAIDs. Also ask whether he or she has ever undergone radiation treatments. Assess whether the patient has had any GI surgeries, especially a partial gastrectomy, which can cause chronic gastritis.

A history of GI upset, pain and its relationship to eating and sleep patterns, and actions taken to relieve pain are also important. Inquire about any changes in the character of the pain, because this may signal the development of complications. For example, if pain that was once intermittent and relieved by food and antacids becomes constant and radiates to the back or upper quadrant, the patient may have ulcer perforation. However, many people with active duodenal or gastric ulcers report having no ulcer symptoms.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Physical assessment findings may reveal epigastric tenderness, usually located at the midline between the umbilicus and the xiphoid process. If perforation into the peritoneal cavity is present, the patient has a rigid, boardlike abdomen accompanied by rebound tenderness and pain. Initially, auscultation of the abdomen may reveal hyperactive bowel sounds, but these may diminish with progression of the disorder.

Dyspepsia (indigestion) is the most commonly reported symptom associated with PUD. It is typically described as sharp, burning, or gnawing. Some patients may perceive discomfort as a sensation of abdominal pressure or of fullness or hunger. Specific differences between gastric and duodenal ulcers are listed in Table 58-2.

TABLE 58-2

DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES OF GASTRIC AND DUODENAL ULCERS

| FEATURE | GASTRIC ULCER | DUODENAL ULCER |

| Age | Usually 50 yr or older | Usually 50 yr or older |

| Gender | Male/female ratio of 1.1 : 1 | Male/female ratio of 1 : 1 |

| Blood group | No differentiation | Most often type O |

| General nourishment | May be malnourished | Usually well nourished |

| Stomach acid production | Normal secretion or hyposecretion | Hypersecretion |

| Occurrence | Mucosa exposed to acid-pepsin secretion | Mucosa exposed to acid-pepsin secretion |

| Clinical course | Healing and recurrence | Healing and recurrence |

| Pain | Occurs 30-60 min after a meal; at night: rarely Worsened by ingestion of food | Occurs  -3 hr after a meal; at night: often awakens patient between 1 and 2 AM -3 hr after a meal; at night: often awakens patient between 1 and 2 AMRelieved by ingestion of food |

| Response to treatment | Healing with appropriate therapy | Healing with appropriate therapy |

| Hemorrhage | Hematemesis more common than melena | Melena more common than hematemesis |

| Malignant change | Perhaps in less than 10% | Rare |

| Recurrence | Tends to heal, and recurs often in the same location | 60% recur within 1 yr; 90% recur within 2 yr |

| Surrounding mucosa | Atrophic gastritis | No gastritis |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree