Shirley E. Van Zandt

Care of Patients with Sexually Transmitted Disease

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

7 Compare the stages of syphilis.

8 Identify the role of drug therapy in managing patients with STDs.

10 Describe the assessment findings that are typical in patients with STDs.

11 Develop a collaborative plan of care for a patient with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Self-Assessment Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Overview

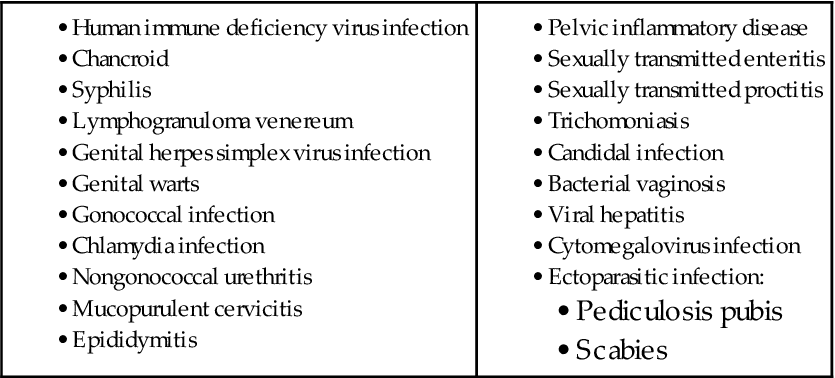

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are caused by infectious organisms that have been passed from one person to another through intimate contact, usually oral, vaginal, or anal intercourse. Some organisms that cause these diseases are transmitted only through sexual contact. Other organisms are transmitted also by parenteral exposure to infected blood, fecal-oral transmission, intrauterine transmission to the fetus, and perinatal transmission from mother to neonate (Table 76-1). Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is another term that has been used to describe the same group of health problems. This terminology was intended to focus on the management of these infections and to decrease the social stigma of labeling them as diseases. Though used in the literature, STI is the less common terminology. STD continues to be the most acceptable term used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

TABLE 76-1

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2010). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59 (RR-12), 1-110.

In spite of improved diagnostic techniques, increased knowledge about organisms that can be sexually transmitted, and changes in sexual attitudes and practices, the number of cases of STDs continues to increase. Sexual issues are often sensitive, personal, and controversial, and nurses must respect the patients’ lifestyle. Providing confidentiality is essential for patients to receive correct information, make informed decisions, and obtain appropriate care.

The prevalence of STDs is a major health concern worldwide. Populations at greatest risk for acquiring STDs are pregnant women, adolescents, and men who have sex with men (MSM). External factors such as an increasing population, cultural factors (e.g., earlier first intercourse), political and economic policies, and international travel and migration affect the prevalence of STDs. It is also affected by changing human physiology patterns such as earlier menarche, comorbidities leading to immunosuppression such as from human immune deficiency virus (HIV), or treatments for cancer or organ transplantation. Access to care plays a major role in the risk for acquiring an STD.

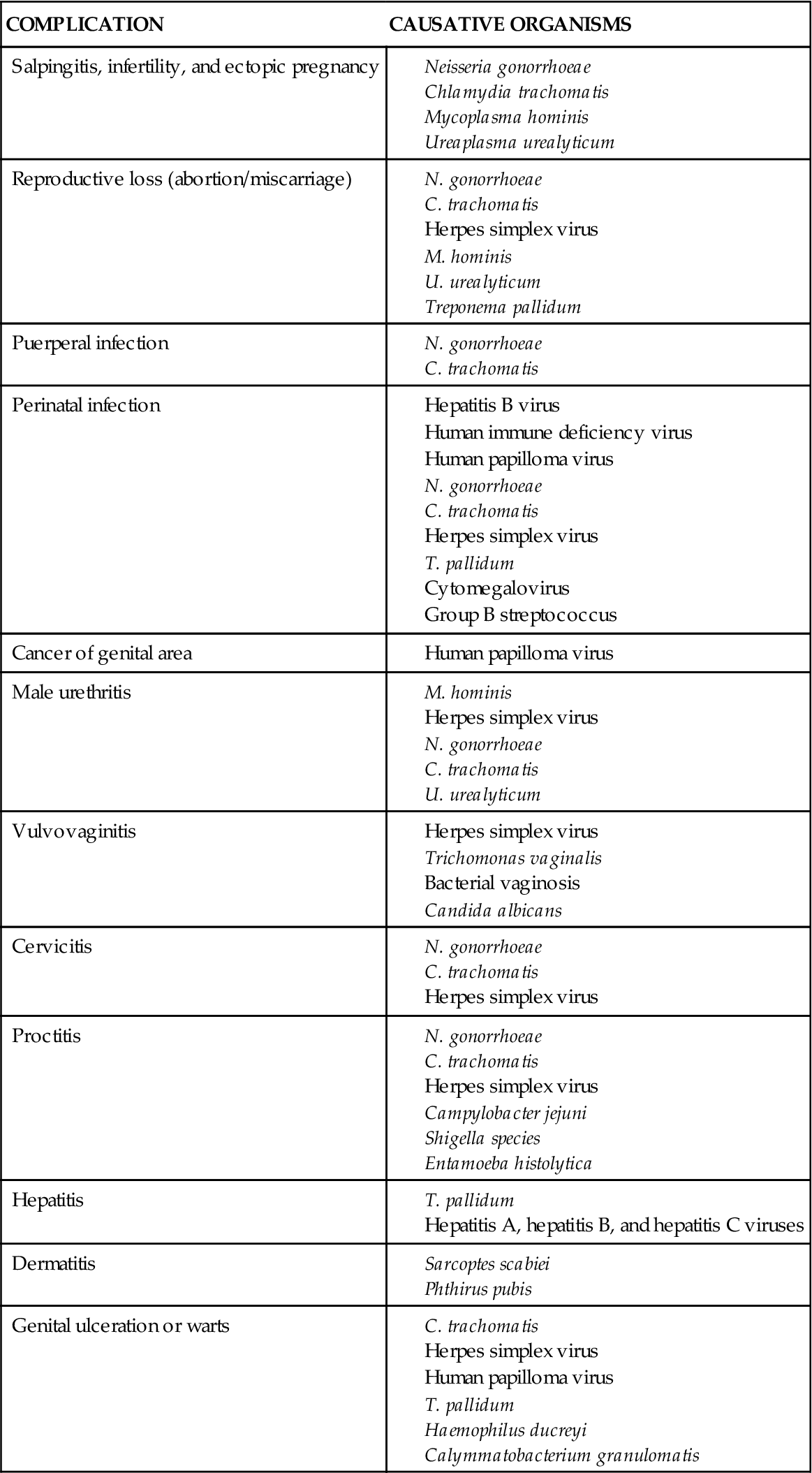

STDs cause complications that can contribute to severe physical and emotional suffering, including infertility, ectopic pregnancy, cancer, and death. Some of the most common complications caused by sexually transmitted organisms are listed in Table 76-2.

TABLE 76-2

COMPLICATIONS CAUSED BY SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED ORGANISMS

Chlamydia infection, gonorrhea, syphilis, chancroid, human immune deficiency virus (HIV) infection, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) are reportable to local health authorities in every state (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008). Other STDs such as genital herpes (GH) may or may not be reported, depending on local legal requirements. Positive results can be reported by clinicians and laboratories. Reports are kept strictly confidential.

Nurses in a variety of settings are responsible for identifying people at risk for STDs, caring for patients with diagnosed STDs, and preventing further cases through education and case finding. Nurses in secondary and tertiary care settings, such as acute care hospitals, have a responsibility to recognize patients who are at risk for or who have STDs, possibly while being treated for another unrelated health problem.

The CDC provides regularly updated guidelines for treatment of STDs. These best practice guidelines provide information, treatment standards, and counseling advice to help decrease the spread of these diseases (CDC, 2010a).

Infections Associated with Ulcers

Syphilis

Pathophysiology

Syphilis is a complex sexually transmitted disease (STD) that can become systemic and cause serious complications, including death. The causative organism is a spirochete called Treponema pallidum. Although the organism can be seen only with a darkfield microscope, several serologic tests may be used to screen for the presence of syphilis antibody. T. pallidum is damaged by dry air or any known disinfectant. The organisms die within hours at temperatures of 105.8° to 107.6° F (41° to 42° C) and are not airborne. The infection is usually transmitted by sexual contact and blood exposure, but transmission can occur through close body contact such as kissing.

Syphilis progresses through four stages: primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary. The appearance of an ulcer called a chancre is the first sign of primary syphilis. It develops at the site of entry (inoculation) of the organism from 10 to 90 days after exposure (3 weeks is average). Chancres may be found on any area of the skin or mucous membranes but occur most often on the genitalia, lips, nipples, and hands and in the mouth, anus, and rectum.

During this highly infectious stage, the chancre begins as a small papule. Within 3 to 7 days, it breaks down into its typical appearance: a painless, indurated (hard), smooth, weeping lesion. Regional lymph nodes enlarge, feel firm, and are not painful. Without treatment, the chancre usually disappears within 6 weeks. However, the organism spreads throughout the body and the patient is still infectious.

Secondary syphilis develops 6 weeks to 6 months after the onset of primary syphilis. During this stage, syphilis is a systemic disease because the spirochetes circulate throughout the bloodstream. Common manifestations include:

These symptoms are often mistaken for those of influenza. The rash, the most commonly presenting symptom, usually involves the palms and soles of the feet. Although it has no typical appearance, the rash tends to change from papules to squamous papules to pustules. Other skin lesions include psoriasis-like rashes (Fig. 76-1), wartlike lesions (condylomata lata), and mucous patches. These lesions are highly contagious and should not be touched without gloves. The rash subsides without treatment in 4 to 12 weeks.

After the second stage of syphilis, there is a period of latency. Early latent syphilis occurs during the first year after infection, and infectious lesions can recur. Late latent syphilis is a disease of more than 1 year’s duration after infection. This stage is not infectious except to the fetus of a pregnant woman. Patients with latent syphilis may or may not have reactive serologic test (e.g., Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL]) findings.

Tertiary, or late, syphilis occurs after a highly variable period, from 4 to 20 years. This stage develops in untreated cases and can mimic other conditions because any organ system can be affected. Manifestations of late syphilis include:

• Benign lesions (gummas) of the skin, mucous membranes, and bones

• Cardiovascular syphilis, usually in the form of aortic valvular disease and aortic aneurysms

Because of strong U.S. public health efforts between 1990 and 1996, there was a 90% decrease in syphilis cases to an all-time low in 2000. Since 2001, there has been a steady increase in cases of primary and secondary syphilis with the majority among men having sex with men (MSM) (CDC, 2009).

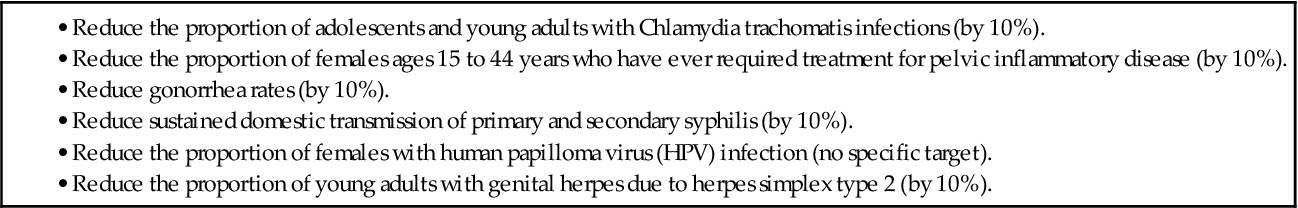

Health Promotion and Maintenance

One of the Healthy People 2020 objectives is to completely eliminate syphilis in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010) (Table 76-3). The most important tool for prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including syphilis, is education. All people, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, or sexual orientation, are susceptible to these diseases. STDs are largely preventable through safer sex practices. Do not assume that a person is not sexually active because of his or her age, education, marital status, profession, or religion. Discuss prevention methods, including safe sex, with all patients who are or may become sexually active.

TABLE 76-3

MEETING HEALTHY PEOPLE 2020 OBJECTIVES AND TARGETS FOR IMPROVEMENT: SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES

Safe sex practices are those that reduce the risk for nonintact skin or mucous membranes coming in contact with infected body fluids and blood. These practices include using:

• A latex or polyurethane condom for genital and anal intercourse

• Gloves for finger or hand contact with the vagina or rectum

Abstinence, mutual monogamy, and decreasing the number of sexual partners also decrease the risk for acquiring an STD.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Assessment of the patient who has manifestations of syphilis begins with a history to gather information about any ulcers or rash. Take a sexual history and conduct a risk assessment to include whether previous testing or treatment for syphilis or other STDs has ever been done (Chart 76-1). Ask about allergic reactions to drugs, especially penicillin. A woman may report inguinal lymph node enlargement resulting from a chancre in the vagina or cervix that is not easily visible to her. She may state a history of sexual contact with a male partner who had an ulcer that she noticed during the encounter. Men usually discover the chancre on the penis or scrotum.

Conduct a physical examination, including inspection and palpation, to identify manifestations of syphilis. Wear gloves while palpating any lesions because of the highly contagious treponemes that are present. Observe for and document rashes of any type because of the variable presentation of secondary syphilis.

After the physical examination, the health care provider obtains a specimen of the chancre for examination under a darkfield microscope. Diagnosis of primary or secondary syphilis is confirmed if T. pallidum is present.

Blood tests are also used to diagnose syphilis. The usual screening and/or diagnostic nontreponemal tests are the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) serum test and the more sensitive rapid plasma reagin (RPR). These tests are based on an antibody-antigen reaction that determines the presence and amount of antibodies produced by the body in response to an infection by T. pallidum. They become reactive 2 to 6 weeks after infection. VDRL titers are also used to monitor treatment effectiveness. The antibodies are not specific to T. pallidum, and false-positive reactions often occur from such conditions as viral infections, hepatitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

If a VDRL result is positive, the health care provider requests or the laboratory may automatically perform a more specific treponemal test, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test or the microhemagglutination assay for T. palladium (MHA-TP), to confirm the infection. These tests are more sensitive for all stages of syphilis, although false-positive results may still occur. Patients who have a reactive test will have this positive result for their entire life, even after sufficient treatment. This poses a challenge when receiving a positive result for a patient who denies a history of or does not know he or she had syphilis.

Interventions

Patient-centered collaborative care includes drug therapy and health teaching to resolve the infection and prevent infection transmission to others.

Drug Therapy

Benzathine penicillin G given IM as a single 2.4 million-unit dose is the evidence-based treatment for primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis (CDC, 2010a). Patients in the late latent stage receive the same dose every week for 3 weeks (CDC, 2010a).

After treatment, the CDC recommends follow-up evaluation including blood tests at 6, 12, and 24 months. Repeat treatment may be needed if the patient does not respond to the initial antibiotic.

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction may also follow antibiotic therapy for syphilis. This reaction is caused by the rapid release of products from the disruption of the cells of the organism. Symptoms include generalized aches, pain at the injection site, vasodilation, hypotension, and fever. They are usually benign and begin within 2 hours after therapy with a peak at 4 to 8 hours. This reaction may be treated symptomatically with analgesics and antipyretics.

Teaching for Self-Management

Reinforce teaching about the cause of infection (sexual transmission); treatment, including side effects; possible complications of untreated or incompletely treated disease; and the need for follow-up care.

Inform the patient that the disease will be reported to the local health authority and that all information will be held in strict confidence. Encourage the patient to provide accurate information for this follow-up to ensure that all at-risk partners are treated appropriately. Provide a setting that offers privacy and encourages open discussion. Urge the patient to adhere to the treatment regimen, which includes follow-up visits. Also recommend sexual abstinence until the treatment of both the patient and partner(s) is completed.

The emotional responses to syphilis vary and may include feelings of fear, depression, guilt, and anxiety. Patients may experience guilt if they have infected others or anger if they have been infected by a partner. If further psychosocial interventions are needed, encourage the patient to discuss these feelings or refer him or her to other resources such as psychotherapy groups, self-help support groups, or STD clinics.

Genital Herpes

Pathophysiology

Genital herpes (GH) is an acute, recurring, incurable viral disease. It is the most common STD in the United States, with 16.2% of Americans currently infected with herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). The prevalence among African Americans is 39.2%, disproportionately affecting African-American women (48.0%) (CDC, 2010b). These rates are based on the presence of HSV-2 antibodies in the blood of those tested, the majority of whom have had no symptoms and most have never received a diagnosis of GH infection (CDC, 2010b).

Two serotypes of herpes simplex virus (HSV) affect the genitalia: type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2). Most nongenital lesions such as cold sores are caused by HSV-1. Historically, HSV-2 caused most of the genital lesions. However, this distinction is academic because the transmission, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment are nearly identical for the two types. Either type can produce oral or genital lesions through oral-genital contact with an infected person. HSV-2 has been thought to cause the majority of the primary episodes of GH, though up to one-third are caused by HSV-1 (Drugge & Allen, 2008). HSV-2 recurs and sheds asymptomatically more often than HSV-1. Most people with GH have not been diagnosed because they have mild symptoms and shed virus intermittently (CDC, 2010a).

The incubation period of genital herpes is 2 to 20 days, with the average period being 1 week. Many people do not have symptoms during the primary outbreak. When outbreaks occur, they are usually more severe than in recurrent outbreaks and occasionally require hospitalization.

Recurrences are not caused by re-infection. Additional episodes are usually less severe and of shorter duration than the primary infection episode. Some patients have no symptoms at all during recurrence or viral reactivation. However, there is viral shedding and the patient is infectious. Long-term complications of GH include the risk for neonatal transmission and an increased risk for acquiring HIV infection.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

The diagnosis of GH is usually based on the patient’s history and physical examination (see Chart 76-1). Ask the patient if he or she felt itching or a tingling sensation in the skin 1 to 2 days before the outbreak. These sensations are usually followed by the appearance of vesicles (blisters) in a typical cluster on the penis, scrotum, vulva, vagina, cervix, or perianal region. The blisters rupture spontaneously in a day or two and leave painful erosions that can become extensive. Assess for other symptoms such as headaches, fever, general malaise, and swelling of inguinal lymph nodes. Ask if urination is painful. Patients with urinary retention may need to be catheterized. Lesions resolve within 2 to 6 weeks.

After the lesions heal, the virus remains in a dormant state in the nerve ganglia (specifically, the sacral ganglia). Periodically, the virus may activate and symptoms recur. These recurrences may be triggered by many factors, including stress, fever, sunburn, poor nutrition, menses, and sexual activity. Assess the patient for these risk factors.

GH is confirmed through a viral culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays of the lesions. PCR is the more sensitive test. Fluid from inside the blister should be obtained within 48 hours of the first outbreak of the blisters, since accuracy decreases as they begin to heal. Serology testing, which is glycoprotein G antibody-based, can identify the HSV type, either 1 or 2. Serologic tests are used to identify infection in high-risk groups such as HIV-positive patients, patients who have partners with HSV, or MSM (CDC, 2010a). The POCkit HSV-2 Rapid Test is a point-of-care test with results in 6 minutes. The HerpeSelect Immunoblot IgG test, HerpeSelect ELISA, and the Western Blot are qualitative assays that can differentiate between HSV-1 and HSV-2. All of these tests are highly specific and sensitive (Bavis et al., 2009).

Interventions

The desired outcomes of treatment for HSV-infected patients are to decrease the discomfort from painful ulcerations, promote healing without secondary infection, decrease viral shedding, and prevent infection transmission (Chart 76-2).