Chris Winkelman

Care of Patients with Renal Disorders

Learning Outcomes

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

9 Explain the genetics of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

11 Describe the clinical manifestations of hydronephrosis.

12 Explain the relationship between hypertension and kidney disease.

13 Coordinate nursing care for the patient with pyelonephritis.

14 Coordinate nursing care for the patient during the first 24 hours after a nephrectomy.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

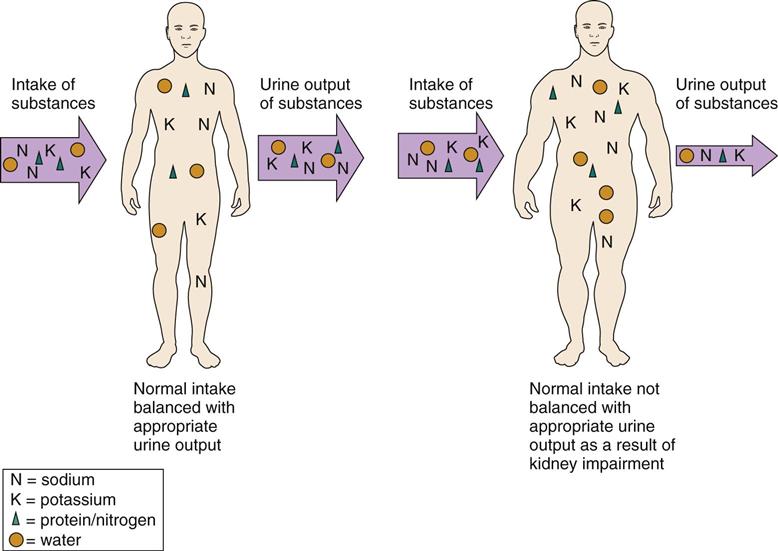

The kidneys participate in urinary elimination by filtering wastes and balancing fluids, electrolytes, acids, and bases. Any problem that disrupts kidney function limits the ability to meet that need and has the potential to impair general homeostasis (Fig. 70-1). The kidneys work together with many other organ systems. Thus kidney disorders affect systemic health and can lead to life-threatening outcomes. Kidney disorders are classified as congenital, obstructive, infectious, glomerular, and degenerative. Kidney tumors and kidney trauma are also described in this chapter. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease are discussed in Chapter 71.

Congenital Disorders

Polycystic Kidney Disease

Pathophysiology

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is an inherited disorder in which fluid-filled cysts develop in the nephrons. In the dominant form, only a few nephrons have cysts until the person reaches his or her 30s. In the recessive form of the disease, nearly 100% of nephrons have cysts from birth. Cysts develop anywhere in the nephron as a result of abnormal kidney cell division.

Over time, small cysts become much larger (up to a few centimeters in diameter) and more widely distributed. The growing cysts damage the glomerular and tubular membranes. As the cysts fill with fluid and enlarge, the nephron and kidney function become less effective.

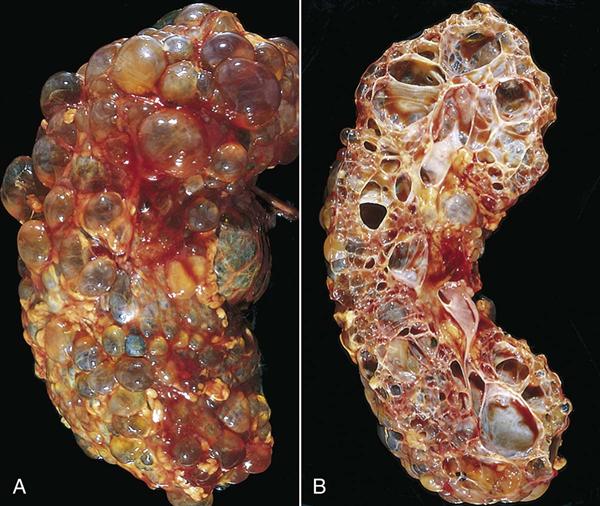

The kidney tissue is eventually replaced by nonfunctioning cysts, which look like clusters of grapes (Fig. 70-2). The kidneys become very large. Each cystic kidney may enlarge to two or three times its normal size, becoming as large as a football, and may weigh 10 pounds or more each. Other abdominal organs are displaced, and the patient has pain. The fluid-filled cysts are also at increased risk for infection, rupture, and bleeding, which increase pain.

Most patients with PKD have high blood pressure. The cause of hypertension is related to kidney ischemia from the enlarging cysts. As the vessels are compressed and blood flow to the kidneys decreases, the renin-angiotensin system is activated, raising blood pressure. Control of hypertension is a top priority because proper treatment can disrupt the process that leads to further kidney damage.

Cysts may occur also in other tissues, such as the liver and blood vessels. They may reduce liver function. In addition, the incidence of cerebral aneurysms (outpouching and thinning of an artery wall) is higher in patients with PKD. These aneurysms may rupture, causing bleeding and sudden death. For reasons as yet unknown, kidney stones occur in 8% to 36% of the patients with PKD. Heart valve problems (e.g., mitral valve prolapse), left ventricular hypertrophy, and colonic diverticula also are common in patients with PKD.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

PKD has several forms and can be inherited as either an autosomal dominant trait or, less commonly, as an autosomal recessive trait. People who inherit the recessive form of PKD usually die in early childhood. The 5% to 10% incidence of PKD in patients with no family history occurs as a result of a new gene mutation.

Autosomal recessive PKD is rare, and most people with the disease die in early childhood. It is caused by a gene mutation different from the dominant form. To inherit a recessive gene, both parents must carry a copy of the mutated allele and both mutated alleles must be inherited. Thus each child has a 1-in-4 chance of inheriting autosomal recessive polycystic disease.

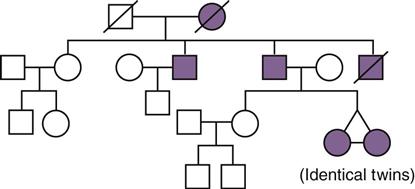

There is no way to prevent PKD, although early detection and management of hypertension may slow the progression of kidney damage. Genetic counseling may be useful for adults who have one parent or both parents with PKD. Family history analysis is a simple assessment that can be used to help identify people at risk for PKD (see Fig. 70-3).

Incidence/Prevalence

PKD is a common disorder, affecting 250,000 to 500,000 people in the United States. It is more common in white people than in people of other races. Men and women have an equal chance of inheriting the disease because the gene responsible for PKD is not located on the sex chromosomes (Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation, 2011).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Explore the family history of a patient with suspected or actual PKD, and ask whether either parent was known to have PKD or whether there is any family history of kidney disease. The age at which the problem was diagnosed in the parent and any related complications are important to obtain. Ask about constipation, abdominal discomfort, a change in urine color or frequency, high blood pressure, headaches, and a family history of sudden death from a stroke.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

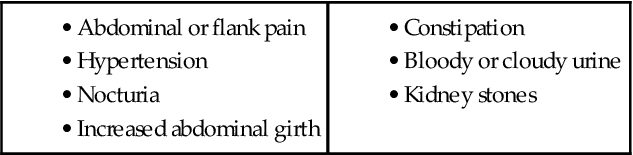

Chart 70-1 lists key features of PKD. Pain is often the first manifestation. Inspect the abdomen. A distended abdomen is common as the cystic kidneys swell and push the abdominal contents forward. Polycystic kidneys are easily palpated because of their increased size. Proceed with gentle abdominal palpation because the cystic kidneys and nearby tissues may be tender and palpation is uncomfortable.

The patient also may have flank pain as a dull ache or as sharp and intermittent discomfort. Dull, aching pain is caused by increased kidney size with distention or by infection within the cyst. Sharp, intermittent pain occurs when a cyst ruptures or a stone is present. When a cyst ruptures, the patient may have bright red or cola-colored urine. Infection is suspected if the urine is cloudy or foul smelling or if there is dysuria (pain on urination).

Nocturia (the need to urinate excessively at night) is an early manifestation and occurs because of decreased urine concentrating ability. As kidney function further declines, the patient has increasing hypertension, edema, and uremic manifestations such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and fatigue (see Chapter 71). Because berry aneurysms often occur in patients with PKD, a severe headache with or without neurologic or vision changes requires attention.

Psychosocial Assessment

As an inherited disorder, PKD may cause psychosocial responses. The patient often has seen the effects and problems of the disease in close family members. He or she may have had a parent who died or close relatives who required dialysis or transplantation. While obtaining the family history, listen carefully for spoken and unspoken feelings of anger, resentment, futility, sadness, or anxiety. Such feelings may need further exploration. The focus of the feelings may be one or both parents or the process of diagnosis and treatment. Feelings of guilt and concern for the patient’s children may also complicate the issue.

Diagnostic Assessment

Urinalysis shows proteinuria (protein in the urine) once the glomeruli are involved. Hematuria (blood in the urine) may be gross or microscopic. Bacteria in the urine indicate infection, usually in the cysts. Obtain a urine sample for culture and sensitivity testing when there is evidence of infection. As kidney function declines, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels rise. With decreasing kidney function, creatinine clearance decreases. Changes in kidney handling of sodium may cause either sodium losses or sodium retention.

Diagnostic studies include renal sonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Small cysts are detected by sonography, CT, or MRI. Renal sonography shows evidence of PKD, with minimal risk.

Interventions

Interventions for the patient with PKD include pain management and prevention of infection, constipation, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. When the disease progresses to the point that the kidneys no longer function to clear wastes, care becomes similar to that needed for the patient with end-stage kidney disease (see Chapter 71).

Managing Pain

Comfort strategies include drug therapy and complementary approaches. A combination may be most effective. NSAIDs are used cautiously because of their tendency to reduce kidney blood flow. Aspirin-containing compounds are avoided to reduce the risk for bleeding.

If cyst infection causes discomfort, antibiotics such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra, Trimpex) or ciprofloxacin (Cipro) are prescribed. (See Chart 69-4 in Chapter 69.) These drugs enter the cyst wall. Monitor the serum creatinine levels because antibiotic therapy can be nephrotoxic. Apply dry heat to the abdomen or flank to promote comfort when kidney cysts are infected. When pain is severe, cysts can be reduced by needle aspiration and drainage; however, they usually refill.

Teach the patient methods of relaxation and comfort using deep breathing, guided imagery, or other strategies. The expected outcome is patient self-management. (See Chapter 5 for pain management.)

Preventing Constipation

Teach the patient who has adequate urine output how to prevent constipation by maintaining adequate fluid intake, increasing dietary fiber when fluid intake is more than 2500 mL/24 hr, and exercising regularly. Explain that pressure on the large intestine may occur as the polycystic kidneys increase in size. The patient should know that these recommendations for bowel management might change, particularly if end-stage kidney disease also develops. Advise him or her about the use of stool softeners and bulk agents, including the careful use of laxatives, to prevent chronic constipation.

Controlling Hypertension and Preventing End-Stage Kidney Disease

Blood pressure control is necessary to reduce cardiovascular complications and slow the progression of kidney dysfunction. Nursing interventions include education to promote self-management and understanding. When kidney impairment results in decreased urine concentration with nocturia and low urine specific gravity, urge the patient to drink at least 2 L of fluid per day to prevent dehydration, which can further reduce kidney function. Restricting sodium intake may help control blood pressure. See Chapter 38 for a detailed discussion about the causes and management of hypertension.

Drug therapy for blood pressure control includes antihypertensive agents and diuretics. Antihypertensive agents include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, and vasodilators (see Chapter 38). ACE inhibitors may help control the cell growth aspects of PKD and reduce microalbuminuria.

Teach the patient and family how to measure and record blood pressure. Help the patient establish a schedule for self-administering drugs, monitoring daily weights, and keeping blood pressure records (Chart 70-2). Explain the potential side effects of the drugs. Make available written materials, such as drug teaching cards and booklets.

A low-sodium diet is often prescribed to control the hypertension that usually occurs with PKD. However, some patients may have salt wasting and should not follow a sodium-restricted diet. As the disease progresses, the protein intake may be limited to slow the development of end-stage kidney disease. Assist the patient and family in understanding the diet plan and why it was prescribed. Work closely with the dietitian to foster the patient’s understanding. Also refer the patient for nutritional counseling.

Health Care Resources

The Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation (www.pkdcure.org) and the National Kidney & Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NKUDIC) of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (www2.niddk.nih.gov) conduct research and provide education about PKD. Many pamphlets are available; there is a fee for some materials. Chapters of the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and the American Association of Kidney Patients (AAKP) also have resources for information and support.

Obstructive Disorders

Hydronephrosis, Hydroureter, and Urethral Stricture

Pathophysiology

Hydronephrosis and hydroureter are problems of urine outflow obstruction. Urethral strictures also obstruct urine outflow. Prompt recognition and treatment are crucial to prevent permanent kidney damage.

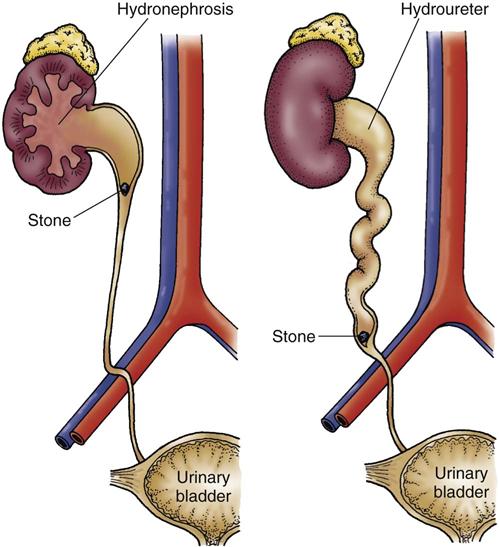

In hydronephrosis, the kidney enlarges as urine collects in the renal pelvis and kidney tissue. Because the capacity of the renal pelvis is normally 5 to 8 mL, obstruction in the pelvis or at the point where the ureter joins the renal pelvis quickly distends the renal pelvis. Kidney pressure increases as the volume of urine increases. Over time, sometimes in only a matter of hours, the blood vessels and kidney tubules can be damaged extensively (Fig. 70-4).

In patients with hydroureter (enlargement of the ureter), the effects are similar but the obstruction is in the ureter rather than in the kidney. The ureter is most easily obstructed where the iliac vessels cross or where the ureters enter the bladder. Ureter dilation occurs above the obstruction and enlarges as urine collects (see Fig. 70-4).

In patients with a urethral stricture, the obstruction is very low in the urinary tract, causing bladder distention before hydroureter and hydronephrosis. The problems and kidney damage are similar without prompt treatment.

Urinary obstruction causes damage when pressure builds up directly on kidney tissue. Tubular filtrate pressure also increases in the nephron as drainage through the collecting system is impaired. With this added pressure, glomerular filtration decreases or ceases, and complete necrosis of the affected kidney can occur. Nitrogen waste products (urea, creatinine, and uric acid) and electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, and phosphorus) are retained, and acid-base balance is impaired.

Causes of hydronephrosis or hydroureter include tumors, stones, trauma, structural defects, and fibrosis. In patients with cancer, obstructed ureters may result from the tumors themselves, pelvic radiation, or surgical treatment. Early treatment of the causes can prevent hydronephrosis and hydroureter and thus prevent permanent kidney damage. The specific time needed to prevent permanent damage depends on the patient’s kidney health. Permanent damage can occur in less than 48 hours in some patients and after several weeks in other patients.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Obtain a history from the patient, focusing on known kidney or urologic disorders. A history of childhood urinary tract problems may indicate previously undiagnosed structural defects. Ask about his or her usual pattern of urination, especially amount, frequency, color, clarity, and odor. Ask about recent flank or abdominal pain. Chills, fever, and malaise may be present with a urinary tract infection (UTI).

Inspect each flank to identify asymmetry, which may occur with a kidney mass, and gently palpate the abdomen to locate areas of tenderness. Palpate and percuss the bladder to detect distention, or use a bedside bladder scanner. Gentle pressure on the abdomen may cause urine leakage, which reflects a full bladder and possible obstruction.

Urinalysis may show bacteria or white blood cells if infection is present. When urinary tract obstruction is prolonged, microscopic examination may show tubular epithelial cells. Blood chemistries are normal unless glomerular filtration decreases. Blood creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels increase with a reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Serum electrolyte levels may be altered with elevated blood levels of potassium, phosphorus, and calcium along with a metabolic acidosis (bicarbonate deficit).

IV urography shows ureteral or renal pelvis dilation. Urinary outflow obstruction can be seen with sonography (renal echography) or computed tomography (CT).

Interventions

Urinary retention and potential for infection are the primary problems. Failure to treat the cause of obstruction leads to infection and end-stage kidney disease.

Urologic Interventions

If the stricture is caused by a stone, it can be located and removed using cystoscopic or retrograde urogram procedures. The urologist uses a cystoscope to guide a stone basket over the stone and removes it through the bladder. After stone removal, a plastic stent is usually left in the ureter for a few weeks to improve urine flow in the area irritated by the stone. The stent is later removed by another cystoscopic procedure.

Radiologic Interventions

When a stricture is causing hydronephrosis and cannot be corrected with urologic procedures, a nephrostomy is performed. This procedure diverts urine externally and prevents further damage to the kidney.

Patient Preparation.

If possible, the patient is kept NPO for 4 to 6 hours before the procedure. Clotting studies (e.g., international normalized ratio [INR], prothrombin time [PT], and partial thromboplastic time [PTT]) should be normal or corrected. The patient receives moderate sedation for the procedure.

Procedure.

The patient is placed in the prone position. The kidney is located under ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance, and a local anesthetic is given. A needle is placed into the kidney, a soft-tipped guidewire is placed through the needle, and then a catheter is placed over the wire. The catheter tip remains in the renal pelvis, and the external end is connected to a drainage bag. The procedure immediately relieves the pressure and prevents further damage. The nephrostomy tube remains in place until the obstruction is resolved (with or without further intervention).

Follow-up Care.

Assess the amount of drainage in the collection bag. The amount of drainage depends on whether a ureteral catheter is also being used (with a separate drainage bag). Patients with ureteral tubes may have all urine pass through to the bladder or may have urine drain into the collection bags. The type of urine drainage expected should be clearly communicated in the chart. If urine is expected to drain into the collection bag, assess the amount of drainage hourly for the first 24 hours. If the amount of drainage decreases and the patient has back pain, the tube may be clogged or dislodged.

Monitor the nephrostomy site for leaking urine or blood. Urine drainage may be red-tinged for the first 12 to 24 hours after the procedure and should gradually clear. Assess the patient for manifestations of infection, including fever or a change in urine character.

Infectious Disorders: Pyelonephritis

In the healthy person, urine is normally sterile and remains sterile if there is no obstruction to urine passage in the kidney and urinary tract. When any structural abnormality is present, the risk for damage as a result of infection is greatly increased. Urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection in this normally sterile system. Pyelonephritis is a bacterial infection in the kidney and renal pelvis.

Pathophysiology

Pyelonephritis is either the presence of active organisms in the kidney or the effects of kidney infections. Acute pyelonephritis is the active bacterial infection, whereas chronic pyelonephritis results from repeated or continued upper urinary tract infections or the effects of such infections. Chronic pyelonephritis often occurs with a urinary tract defect, obstruction, or, most commonly, when urine refluxes from the bladder back into the ureters. The vesicoureteral junction is the point at which the ureter joins the bladder. Reflux is the reverse or upward flow of urine toward the renal pelvis and kidney.

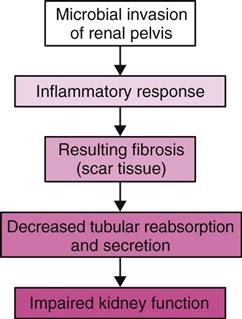

In pyelonephritis, organisms move up from the urinary tract into the kidney tissue. Descending infection transmitted by organisms in the blood may occur, but not often. Bacteria trigger the inflammatory response, and local edema results.

Acute pyelonephritis involves acute tissue inflammation, tubular cell necrosis, and possible abscess formation. Abscesses, which are pockets of infection with pus, can occur anywhere in the kidney. The infection is scattered within the kidney; healthy tissues can lie next to infected areas. Fibrosis and scar tissue develop from the inflammation. The calices thicken, and scars develop in the interstitial tissue.

Reflux of infected urine from the bladder into the ureters and kidney is responsible for most cases of chronic pyelonephritis. Reflux within the kidney can occur when some papillae in the kidney do not close properly. Inflammation and fibrosis lead to deformity of the renal pelvis and calices. Repeated or continuous infections create additional scar tissue, changing blood vessel, glomerular, and tubular structure. As a result, filtration, reabsorption, and secretion are impaired and kidney function is reduced (Fig. 70-5).

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Single episodes of acute pyelonephritis may result from the entry of bacteria, especially during pregnancy, obstruction, or reflux. Chronic pyelonephritis usually occurs with structural deformities or obstruction with reflux. Reflux or obstruction leading to chronic pyelonephritis is often caused by stones or neurogenic impairment of voiding. Reflux is more common in children who have acquired scarring during acute infection or as a result of anatomic anomalies. Reflux and scarring contribute to chronic pyelonephritis as an adult. Chronic pyelonephritis in adults who did not have reflux as a child usually occurs with spinal cord injury, bladder tumor, prostate enlargement, or urinary tract stones.

Acute or chronic pyelonephritis occurs often in patients who have undergone manipulation of the urinary tract (e.g., placement of a urinary catheter), those with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney stones, or those who overuse analgesics. In those with diabetes mellitus, the reduced bladder tone increases the risk for pyelonephritis. In patients with chronic stone disease, stones may retain organisms, resulting in ongoing infection and kidney scarring. NSAID use can lead to papillary necrosis and reflux.

The most common pyelonephritis-causing organism is Escherichia coli. Enterococcus faecalis is common in hospitalized patients. Both organisms are in the intestinal tract. Other organisms that cause pyelonephritis in hospitalized patients include Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. When the infection is bloodborne, common infecting organisms include Staphylococcus aureus and the Candida and Salmonella species.

Other causes of kidney scarring leading to kidney function impairment include antibody reactions, cell-mediated immunity against the bacterial antigens, or autoimmune reactions.

Incidence/Prevalence

There are approximately 250,000 cases of acute pyelonephritis each year, resulting in more than 100,000 hospitalizations. Chronic pyelonephritis is commonly associated with vesicoureteral reflux or other anatomic abnormalities and is more common in women, although exact numbers for incidence and prevalence are not available. After 65 years of age, rates of pyelonephritis for men increase greatly because of the increased incidence of prostatitis and enlarged prostate.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Ask about a history of urinary tract infections (UTIs), diabetes mellitus, stone disease, and defects of the genitourinary tract. Determine whether the UTIs occurred with pregnancy, and ask the patient about any previous episodes of pyelonephritis or similar symptoms. Ask about disease or treatment that causes immunosuppression, because they can also increase risk for pyelonephritis. Recurrences are common and may lead to a decline of kidney function.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Ask about specific manifestations of acute pyelonephritis (Chart 70-3). Chronic pyelonephritis has a less dramatic presentation, with manifestations related to the infection or kidney function. Ask the patient to describe any vague or nonspecific urinary symptoms or abdominal discomfort. Inquire about any history of repeated low-grade fevers. The patient with chronic pyelonephritis often has bacteruria that causes no symptoms. Chart 70-4 outlines the kidney effects of chronic pyelonephritis.