Chapter 70 Care of Patients with Renal Disorders

Health Promotion and Maintenance

1. Encourage patients with diabetes to achieve tight glycemic control.

2. Encourage patients with hypertension to follow their treatment regimens to maintain blood pressure within the target range.

3. Teach patients at risk for urinary tract infection (UTI) to maintain a daily fluid intake of 2 L unless another health problem requires fluid restriction.

4. Teach patients on antibiotic therapy for a UTI to complete the drug regimen.

6. Use language the patient is comfortable with during assessment of the kidney and urinary system.

7. Encourage the patient to express feelings or concerns about a change in kidney function.

9. Explain the genetics of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

10. Use laboratory data and clinical manifestations to determine the effectiveness of therapy for pyelonephritis.

11. Describe the clinical manifestations of hydronephrosis.

12. Explain the relationship between hypertension and kidney disease.

13. Coordinate nursing care for the patient with pyelonephritis.

14. Coordinate nursing care for the patient during the first 24 hours after a nephrectomy.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

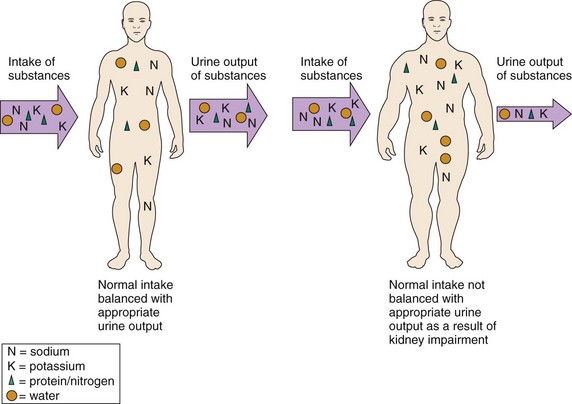

The kidneys participate in urinary elimination by filtering wastes and balancing fluids, electrolytes, acids, and bases. Any problem that disrupts kidney function limits the ability to meet that need and has the potential to impair general homeostasis (Fig. 70-1). The kidneys work together with many other organ systems. Thus kidney disorders affect systemic health and can lead to life-threatening outcomes. Kidney disorders are classified as congenital, obstructive, infectious, glomerular, and degenerative. Kidney tumors and kidney trauma are also described in this chapter. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease are discussed in Chapter 71.

Congenital Disorders

Polycystic Kidney Disease

Pathophysiology

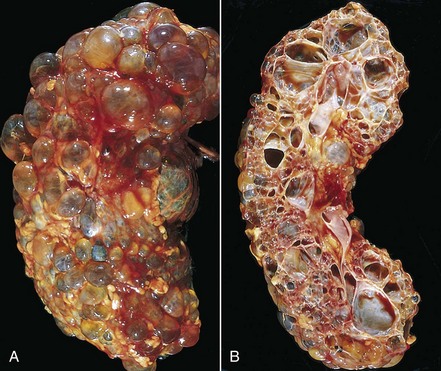

The kidney tissue is eventually replaced by nonfunctioning cysts, which look like clusters of grapes (Fig. 70-2). The kidneys become very large. Each cystic kidney may enlarge to two or three times its normal size, becoming as large as a football, and may weigh 10 pounds or more each. Other abdominal organs are displaced, and the patient has pain. The fluid-filled cysts are also at increased risk for infection, rupture, and bleeding, which increase pain.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Genetic/Genomic Considerations

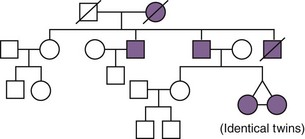

The autosomal dominant form of PKD (ADPKD) is the most common form of polycystic disease. Children of parents who have the autosomal dominant form of PKD have a 50% chance of inheriting the gene that causes the disease. Fig. 70-3 shows a typical pedigree for a family with ADPKD. Presentation of ADPKD can vary for age of onset, manifestations, and illness severity, even within one family. However, it is highly penetrant, meaning that nearly 100% of people who inherit a PKD gene will develop kidney cysts by age 30 (Nussbaum et al., 2007). Half of these people develop chronic kidney disease by age 50 years. ADPKD-1 is the most common and most severe form of the autosomal dominant disease. ADPKD-2 has a slower rate of cyst formation, so symptoms occur later in life and progression to end-stage kidney disease and other complications is delayed.

There is no way to prevent PKD, although early detection and management of hypertension may slow the progression of kidney damage. Genetic counseling may be useful for adults who have one parent or both parents with PKD. Family history analysis is a simple assessment that can be used to help identify people at risk for PKD (see Fig. 70-3).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Chart 70-1 lists key features of PKD. Pain is often the first manifestation. Inspect the abdomen. A distended abdomen is common as the cystic kidneys swell and push the abdominal contents forward. Polycystic kidneys are easily palpated because of their increased size. Proceed with gentle abdominal palpation because the cystic kidneys and nearby tissues may be tender and palpation is uncomfortable.

Polycystic Kidney Disease

Nocturia (the need to urinate excessively at night) is an early manifestation and occurs because of decreased urine concentrating ability. As kidney function further declines, the patient has increasing hypertension, edema, and uremic manifestations such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and fatigue (see Chapter 71). Because berry aneurysms often occur in patients with PKD, a severe headache with or without neurologic or vision changes requires attention.

Diagnostic Assessment

Patient-Centered Care; Teamwork and Collaboration

The 36-year-old unaffected daughter of a 63-year-old man with PKD is visiting her two 31-year-old sisters (identical twins) who are both hospitalized with acute complications of their PKD (see Fig. 70-3). You find the unaffected sister in the hallway crying. She tells you that she feels sad that her sisters are suffering so much and guilty that she has escaped the disease. She also tells you that, although she wants to donate a kidney to the sister whose disease has already progressed to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), she is not a blood type match. (Both parents have type A blood, the unaffected sister has type A blood, and the affected twin sisters have type O blood.) In addition, she has a 2-year-old son and a 6-week-old son, and she fears that they may either develop the disease or pass it on to their children. She also tells you that she is grateful that her father’s PKD is not as severe as her sisters’ disease.

1. What is the pattern of inheritance for the PKD depicted in Fig. 70-3 (and explain why it could not be another pattern of inheritance)?

2. Are the unaffected sister’s fears of passing the disease on to her children or grandchildren founded or unfounded? Provide a rationale for your decision.

3. Is the unaffected sister correct in thinking that her blood type difference eliminates the possibility that she could donate a kidney to one of her sisters? Why or why not? (You may need to review blood type issues in Chapter 42 and kidney transplantation issues in Chapter 71.)

4. What comments or suggestions could you make to help the unaffected sister feel less guilty about her own good health?

Interventions

Interventions for the patient with PKD include pain management and prevention of infection, constipation, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. When the disease progresses to the point that the kidneys no longer function to clear wastes, care becomes similar to that needed for the patient with end-stage kidney disease (see Chapter 71).

Managing Pain

If cyst infection causes discomfort, antibiotics such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra, Trimpex) or ciprofloxacin (Cipro) are prescribed. (See Chart 69-4 in Chapter 69.) These drugs enter the cyst wall. Monitor the serum creatinine levels because antibiotic therapy can be nephrotoxic. Apply dry heat to the abdomen or flank to promote comfort when kidney cysts are infected. When pain is severe, cysts can be reduced by needle aspiration and drainage; however, they usually refill.

Teach the patient methods of relaxation and comfort using deep breathing, guided imagery, or other strategies. The expected outcome is patient self-management. (See Chapter 5 for pain management.)

Controlling Hypertension and Preventing End-Stage Kidney Disease

Blood pressure control is necessary to reduce cardiovascular complications and slow the progression of kidney dysfunction. Nursing interventions include education to promote self-management and understanding. When kidney impairment results in decreased urine concentration with nocturia and low urine specific gravity, urge the patient to drink at least 2 L of fluid per day to prevent dehydration, which can further reduce kidney function. Restricting sodium intake may help control blood pressure. See Chapter 38 for a detailed discussion about the causes and management of hypertension.

Drug therapy for blood pressure control includes antihypertensive agents and diuretics. Antihypertensive agents include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, and vasodilators (see Chapter 38). ACE inhibitors may help control the cell growth aspects of PKD and reduce microalbuminuria.

Teach the patient and family how to measure and record blood pressure. Help the patient establish a schedule for self-administering drugs, monitoring daily weights, and keeping blood pressure records (Chart 70-2). Explain the potential side effects of the drugs. Make available written materials, such as drug teaching cards and booklets.

Chart 70-2 Patient And Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Polycystic Kidney Disease

• Measure and record your blood pressure daily, and notify your health care provider for consistent changes in blood pressure.

• Take your temperature if you suspect you have a fever.

• Weigh yourself every day at the same time of day and with the same amount of clothing; notify your physician or nurse if you have a sudden weight gain.

• Limit your intake of salt to help control your blood pressure.

• Notify your physician or nurse if your urine smells foul or has blood in it.

• Notify your physician or nurse if you have a headache that does not go away or if you have visual disturbances.

Health Care Resources

The Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation (www.pkdcure.org) and the National Kidney & Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NKUDIC) of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (www2.niddk.nih.gov) conduct research and provide education about PKD. Many pamphlets are available; there is a fee for some materials. Chapters of the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and the American Association of Kidney Patients (AAKP) also have resources for information and support.

Obstructive Disorders

Hydronephrosis, Hydroureter, and Urethral Stricture

Pathophysiology

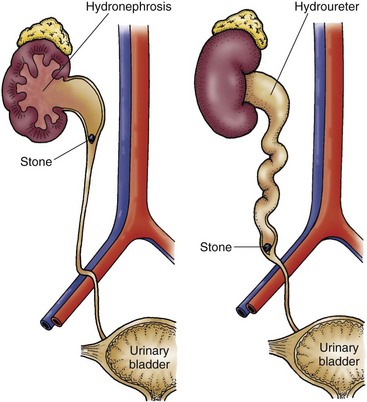

In hydronephrosis, the kidney enlarges as urine collects in the renal pelvis and kidney tissue. Because the capacity of the renal pelvis is normally 5 to 8 mL, obstruction in the pelvis or at the point where the ureter joins the renal pelvis quickly distends the renal pelvis. Kidney pressure increases as the volume of urine increases. Over time, sometimes in only a matter of hours, the blood vessels and kidney tubules can be damaged extensively (Fig. 70-4).

In patients with hydroureter (enlargement of the ureter), the effects are similar but the obstruction is in the ureter rather than in the kidney. The ureter is most easily obstructed where the iliac vessels cross or where the ureters enter the bladder. Ureter dilation occurs above the obstruction and enlarges as urine collects (see Fig. 70-4).

Infectious Disorders: Pyelonephritis

Pathophysiology

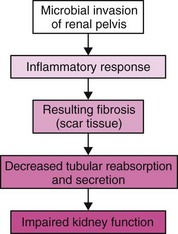

Reflux of infected urine from the bladder into the ureters and kidney is responsible for most cases of chronic pyelonephritis. Reflux within the kidney can occur when some papillae in the kidney do not close properly. Inflammation and fibrosis lead to deformity of the renal pelvis and calices. Repeated or continuous infections create additional scar tissue, changing blood vessel, glomerular, and tubular structure. As a result, filtration, reabsorption, and secretion are impaired and kidney function is reduced (Fig. 70-5).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Ask about specific manifestations of acute pyelonephritis (Chart 70-3). Chronic pyelonephritis has a less dramatic presentation, with manifestations related to the infection or kidney function. Ask the patient to describe any vague or nonspecific urinary symptoms or abdominal discomfort. Inquire about any history of repeated low-grade fevers. The patient with chronic pyelonephritis often has bacteruria that causes no symptoms. Chart 70-4 outlines the kidney effects of chronic pyelonephritis.

Acute Pyelonephritis

Chronic Pyelonephritis

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree