Rachel L. Palmieri

Care of Patients with Problems of the Central Nervous System

The Brain

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

11 Identify triggers for patients with chronic headaches.

12 Compare the assessment findings of migraine, cluster, and tension headaches.

13 Prioritize care for patients with migraine headaches.

14 Differentiate the common types of seizures, including presenting clinical manifestations.

15 Prioritize care for patients experiencing acute seizures and status epilepticus.

16 Describe collaborative care for a patient having a seizure.

17 Implement seizure precautions for patients at risk for acute seizures or status epilepticus.

18 Identify nursing priorities for patients with bacterial meningitis and encephalitis.

19 Describe abnormal neurologic findings in patients with chronic brain problems.

20 Identify the genetic and environmental influences on development of PD, AD, and Huntington disease.

21 Develop a community-based plan of care for a patient with PD and AD.

23 Develop a collaborative plan of care for patients with AD.

25 Develop a teaching plan for caregivers of patients with AD.

26 Identify the need for genetic counseling for patients who have Huntington disease.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Functional Areas of the Brain

Animation: Meningitis

Animation: Parkinson Disease

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The brain is part of the central nervous system (CNS) that functions as the body’s center for controlling mobility (movement), sensation, and cognition. Health problems involving damage of the brain can be acute or chronic. These problems often affect the patient’s level of independence and quality of life. This chapter discusses acute CNS infections and common chronic neurodegenerative diseases of the brain that may impair a person’s needs for mobility and cognition. Care of patients with chronic disorders requires coordination by nurses and other members of the interdisciplinary health care team. The patient and family are the center of the collaborative team in making decisions about the plan of care.

Headaches

Almost everyone has had a headache at some time in his or her life. Some headaches are related to “colds,” allergies, or stress and are temporary. Others can be very serious and potentially life threatening. For example, an abnormal neurologic assessment together with symptoms of a cluster headache may indicate a serious neurologic problem. Patients with these symptoms are referred immediately to their health care provider or the emergency department.

Although there are many types and causes of headaches, the focus of this section is on two common types that cause people to seek medical attention: migraine headaches and cluster headaches. Patients are usually managed in the ambulatory care setting by the primary health care provider. However, it is not unusual for the person in severe pain to seek treatment in the emergency department.

As part of the nursing assessment, ask patients about the pattern of their headaches. For example:

• When do the headaches occur?

• Do certain foods, alcohol, or other things trigger the headaches?

• Have there been any recent changes in your headaches?

• How do you treat the headaches? Does this treatment work?

• Is there a family history of headaches?

• Where do the headaches begin? Do they spread to other areas?

• Do you experience other symptoms with the headaches, such as weakness or changes in speech?

Migraine Headache

Pathophysiology

A migraine headache is a chronic, episodic disorder with multiple subtypes. It is characterized by an intense pain in one side of the head (unilateral) worsening with movement and occurs with either photophobia (sensitive to light) or phonophobia (sensitive to noise). Either moderate to severe nausea or vomiting is also present (McCance et al., 2010). A migraine is classified as a long-duration headache because it usually lasts 4 to 72 hours.

Migraines tend to be familial, and women are affected more commonly than men. Women with anxiety and depressive personalities are particularly predisposed to migraines and other chronic health problems (Tan et al., 2007). Migraine sufferers are also at risk for stroke and epilepsy (McCance et al., 2010).

The cause of migraine headaches is likely a combination of vascular, genetic, neurologic, hormonal, and environmental factors. It is generally agreed that migraine headaches are mediated via the trigeminal vascular system and its central projections. Blood vessels in the brain overreact to a triggering event, causing spasm in the arteries at the base of the brain. This response is followed by arterial constriction and a decrease in cerebral blood flow. Cerebral hypoxia may occur. Platelets clump together, and serotonin, a vasoconstrictor, is released. Other arteries dilate, which triggers the release of prostaglandins (chemicals that cause inflammation and swelling) and other substances that increase sensitivity to pain. Research suggests a role of excessive synaptic glutamate release or decreased removal of glutamate and potassium from the synaptic cleft (Sanchez-del-Rio et al., 2006).

Many patients find that certain factors, or triggers, such as caffeine, red wine, stress, and monosodium glutamate (MSG) tend to cause migraine headache attacks. Each patient is different regarding which environmental factors trigger headaches. For some patients, being stressed or a change in weather can lead to an attack.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Migraines fall into three categories: migraines with aura, migraines without aura, and atypical migraines. An aura is a sensation such as visual changes that signals the onset of a headache or seizure. In a migraine, the aura occurs immediately before the migraine episode. Most headaches are migraines without aura. The key features of migraines are listed in Chart 44-1. Atypical migraines are less common and include menstrual and cluster migraines. The stages of migraine may include:

• Headache phase, which may last a few hours to a few days

• Termination phase, in which the intensity of the headache decreases

• Postprodrome phase, in which the patient is often fatigued, may be irritable, and has muscle pain

The diagnosis of migraine headache is based on the patient’s history and on physical, neurologic, and psychological assessment. The typical migraine is described as a unilateral, fronto-temporal, throbbing pain in the head that is often worse behind one eye or ear. It is often accompanied by a sensitive scalp, anorexia, photophobia (sensitivity to light), phonophobia (sensitivity to noise), and nausea with or without vomiting. The pain and associated symptoms can last from 4 to 72 hours. Patients tend to have the same clinical manifestations each time they have a migraine headache. Some may have to refrain from regular activities for several days if they cannot control or relieve the pain in its early stage.

Some physicians recommend screening migraine patients with the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2 to identify personality traits and possible mental health/behavioral health problems (Tan et al., 2007). Neuroimaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be indicated if the patient has other neurologic findings, a history of seizures, findings not consistent with a migraine, or a change in the severity of the symptoms or frequency of the attacks.

Neuroimaging is also recommended in patients older than 50 years with a new onset of headaches, especially women. Women with a history of migraines with visual symptoms may have an increased risk for stroke (McCance et al., 2010). This risk increases if a migraine with visual symptoms occurred in the past year. Teach women older than 50 years who have migraines about the risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Encourage them to notify their health care provider if they experience symptoms such as facial drooping, arm weakness, or difficulties with speech.

Interventions

Migraine headaches are often not diagnosed or managed following current best practices. Therefore the National Headache Foundation has recommended the “Three R” approach for patients and health care providers (www.headaches.org):

The priority for care of the patient having migraines is pain management. This outcome may be achieved by abortive and preventive therapy. Drug therapy, trigger management, and complementary and alternative therapies are the major approaches to care. Provide detailed patient and family education regarding the collaborative plan of care.

Abortive Therapy

Abortive therapy is aimed at alleviating pain during the aura phase (if present) or soon after the headache has started. Drug therapy is prescribed to manage migraine headaches. Some of the drugs being used have major side effects, contraindications, and nursing implications. The health care provider must consider any other medical conditions that the patient has when prescribing drug therapy. In general, the patient is started on a low dose that is increased until the desired clinical effect is obtained. Table 44-1 lists commonly used drugs for migraine headaches. Many new drugs are being investigated for this painful and often debilitating health problem.

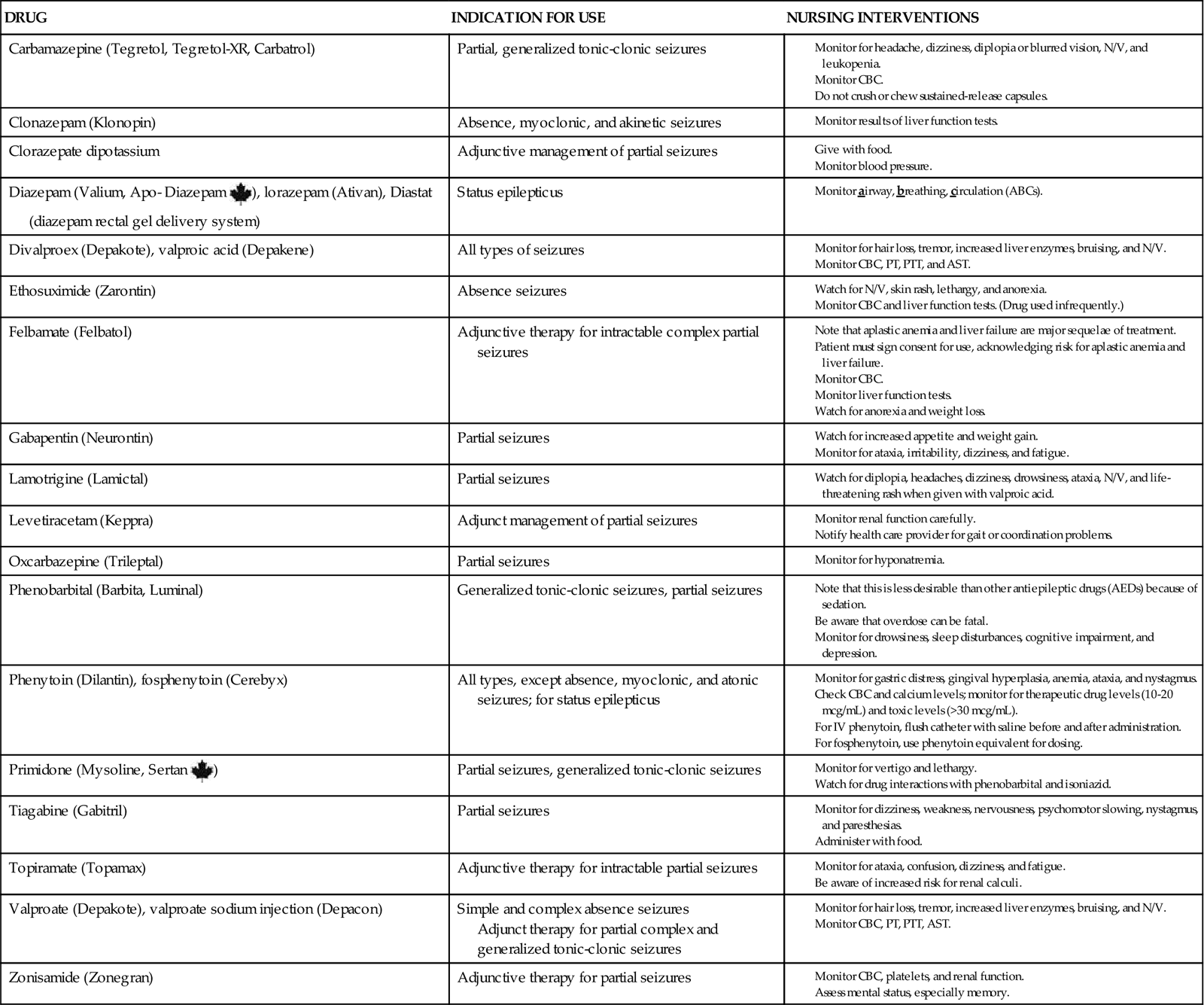

TABLE 44-1

COMMONLY USED DRUGS FOR MIGRAINE HEADACHE

| Nonspecific Analgesics |

| Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) |

| Ergotamine Preparations |

| Beta Blockers |

| Triptan Preparations |

| Isometheptene Combination |

• Midrin |

| Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs) |

Mild migraines may be relieved by acetaminophen (APAP) (Tylenol, Abenol ![]() ). NSAIDs such as ibuprofen (Motrin) and naproxen (Naprosyn) may also be prescribed. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several over-the-counter (OTC) anti-inflammatory drugs for migraines, including Advil Migraine Capsules, Motrin Migraine Pain Caplets, and Excedrin Migraine Tablets or Caplets (contain APAP, aspirin, and caffeine). Caffeine narrows blood vessels by blocking adenosine, which dilates vessels and increases inflammation. Antiemetics may be prescribed to relieve nausea and vomiting. Metoclopramide (Reglan, Clopra) may be administered with NSAIDs to promote gastric emptying and decrease vomiting.

). NSAIDs such as ibuprofen (Motrin) and naproxen (Naprosyn) may also be prescribed. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several over-the-counter (OTC) anti-inflammatory drugs for migraines, including Advil Migraine Capsules, Motrin Migraine Pain Caplets, and Excedrin Migraine Tablets or Caplets (contain APAP, aspirin, and caffeine). Caffeine narrows blood vessels by blocking adenosine, which dilates vessels and increases inflammation. Antiemetics may be prescribed to relieve nausea and vomiting. Metoclopramide (Reglan, Clopra) may be administered with NSAIDs to promote gastric emptying and decrease vomiting.

For more severe migraines, drugs such as triptan preparations, ergotamine derivatives, and isometheptene combinations are needed. A potential side effect of these drugs is rebound headache, also known as medication overuse headache, in which another headache occurs after the drug relieves the initial migraine.

Triptan preparations relieve the headache and associated symptoms by activating the 5-HT (serotonin) receptors on the cranial arteries, the basilar artery, and the blood vessels of the dura mater to produce a vasoconstrictive effect. Examples include zolmitriptan (Zomig) and eletriptan (Relpax). Sumatriptan (Imitrex) is also available in tablets, as an injection, and in a nasal spray. For many patients, these drugs are highly effective for pain, nausea, vomiting, and light and sound sensitivity with few side effects. Most are contraindicated in patients with actual or suspected ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular ischemia, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease and in those with Prinzmetal’s angina because of the potential for coronary vasospasm. Patients respond differently to drugs, and several types or combinations may be tried before the headache is relieved.

Ergotamine preparations such as Cafergot are taken at the start of the headache. The patient may take up to six tablets in 24 hours or use a rectal suppository. Dihydroergotamine (DHE) may be given IV, IM, or as a nasal spray (Migranal) with an antiemetic if pain control and relief of nausea are not achieved with other drugs. DHE should not be given within 24 hours of a triptan drug.

Midrin is a combination drug containing APAP, isometheptene, and dichloralphenazone. It is the most common isometheptene combination given for treating migraines and is an excellent option when ergotamine preparations are not tolerated or do not work.

Other drugs that have been prescribed to relieve migraine pain include opioids and barbiturates. These drugs should be avoided if at all possible because they are addictive. Some opioids actually cause a migraine.

Preventive Therapy

Prevention drugs and other strategies are used when a migraine occurs more than twice per week, interferes with ADLs, or is not relieved with acute treatment. Unless otherwise contraindicated, the health care provider may initially prescribe an NSAID, a beta-adrenergic blocker, a calcium channel blocker, or an antiepileptic drug (AED). Propranolol (Inderal, Apo-Propranolol ![]() , Novopranol

, Novopranol ![]() ) and timolol (Blocadren, Apo-Timol

) and timolol (Blocadren, Apo-Timol ![]() ) are the only beta blockers approved for migraine prevention. Verapamil (Calan, Apo-Verap

) are the only beta blockers approved for migraine prevention. Verapamil (Calan, Apo-Verap ![]() ), a calcium channel blocking agent, may also be used for some patients. Both beta-adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blocking drugs can lower blood pressure and decrease pulse rate.

), a calcium channel blocking agent, may also be used for some patients. Both beta-adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blocking drugs can lower blood pressure and decrease pulse rate.

Topiramate (Topamax) is one of the most common antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) used for migraines, but it should be used in low doses. Reports of suicides have been associated with this drug when it is used in larger doses, most often with patients who have bipolar disorder.

In addition to drug therapy, trigger avoidance and management are important interventions for preventing migraine episodes. For example, some patients find that avoiding tyramine-containing products, such as pickled products, caffeine, beer, wine, preservatives, and artificial sweeteners, reduces their headaches. Others have identified specific factors that trigger an attack for them. Help patients identify triggers that could cause migraine episodes, and teach them to avoid them once identified (Chart 44-2). For example, at the beginning of a migraine attack, the patient may be able to reduce pain by lying down and darkening the room. He or she may want both eyes covered and a cool cloth on the forehead. If the patient falls asleep, he or she should remain undisturbed until awakening.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Many patients use complementary and alternative therapies as adjuncts to drug therapy. Yoga, meditation, massage, exercise, and biofeedback are helpful in preventing or treating migraines for some patients.

Acupuncture and acupressure may be effective in relieving pain for some patients. A number of herbs are also used for headaches, both for prevention and pain management. Teach patients that all herbs and nutritional remedies should be approved by their health care provider before use because they could interact with prescribed medication. At this time, there is insufficient evidence to support any herb or natural remedy, but some patients have had positive results.

Cluster Headache

Pathophysiology

Cluster headaches are manifested by brief (30 minutes to 2 hours), intense unilateral pain that generally occurs in the spring and fall without warning. It is classified as the most common chronic short-duration headache with pain lasting less than 4 hours. Also referred to as trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia, it is far less common than migraines. Cluster headaches typically develop in men between 20 and 50 years of age. The cause and mechanism of cluster headaches are not known but have been attributed to vasoreactivity and neurogenic inflammation (McCance et al., 2010). Neuroimaging studies suggest that cluster headaches are related to an overactive and enlarged hypothalamus.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Question the patient about prescribed drugs for both the prevention and relief of the headache, as well as OTC drugs and herbs he or she may be taking. Interventions used by the patient may include relaxation techniques, meditation, acupuncture, or massage therapies. Ask the patient to recall a typical week’s activities and any recent changes in lifestyle. Ask him or her to identify bedtimes and waking times to help assess changes in activity or lack of continuity in the sleep-wake cycle.

The pain of these unilateral (one-sided) oculotemporal or oculofrontal headaches is often described as excruciating, boring, and nonthrobbing. The intense pain is felt deep in and around the eye. The headaches occur at about the same time of day for about 4 to 12 weeks (hence the term cluster), followed by a period of remission for 9 months to a year. This episodic form is the most common, although there is a chronic, intractable form in which there may not be a remission for more than a year.

The pain may radiate to the forehead, temple, or cheek. It may also radiate, but to a lesser extent, to the ear and neck. The temporal artery may be prominent and tender. The patient often paces, walks, or sits and rocks during an attack. A cluster is the only headache type in which this behavior occurs. During periods of remission, alcohol does not cause a headache (as it does during the headache period). The onset of the pain is associated with relaxation, napping, or rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

The headache usually occurs with:

The ptosis may become permanent. Assess for possible bradycardia, flushing or pallor of the face, increased intraocular pressure, and increased skin temperature. Nausea and vomiting may also occur. The patient may become restless and agitated from the intense pain of the headache.

Interventions

The health care provider typically prescribes some of the same types of drugs used for migraines, such as triptans, ergotamine preparations, and antiepileptic drugs (see discussion of drug therapy in the Migraine Headache section). Additional drugs include calcium channel blockers, especially verapamil (Calan), lithium, and corticosteroids. OTC capsaicin, available as a nasal spray (civamide), melatonin, and glucosamine are also used by some patients. Provide health teaching about drug therapy.

During the periods of attack, teach the patient to wear sunglasses and to sit facing away from the window to help decrease exposure to light and glare. If the health care provider prescribes oxygen, 100% oxygen via mask at 7 to 10 L/min is typically administered with the patient in a sitting position. Administer the oxygen for 15 to 30 minutes, and discontinue it when the headache is relieved. Oxygen reduces cerebral blood flow and inhibits activity of the carotid bodies, which are sensitive to oxygen levels in the body. Patients may use oxygen at home. Teach them about the precautions that must be taken when oxygen is used (see Chapter 30).

To prevent future attacks brought on by precipitating factors (bursts of anger, prolonged anticipation, excessive physical activity, and excitement), discuss their relationship to the onset of cluster headaches. Explain the need for and importance of a consistent sleep-wake cycle.

Surgical intervention may be recommended for patients with chronic drug-resistant cluster headaches. Invasive ambulatory care procedures, such as percutaneous stereotactic rhizotomy (PSR), are performed with varying success rates. Information about this procedure is found in Chapter 46 in the Trigeminal Neuralgia section. Long-term high-frequency electrical stimulation of the posterior hypothalamus, also known as deep brain stimulation, may reduce or eliminate pain (see discussion on p. 946 in the Parkinson Disease section). It has not been approved by the FDA but is being investigated. Both of these procedures have major complications that can cause permanent brain or nerve damage. Therefore they are done as a last resort.

Seizures and Epilepsy

Pathophysiology

A seizure is an abnormal, sudden, excessive, uncontrolled electrical discharge of neurons within the brain that may result in a change in level of consciousness (LOC), motor or sensory ability, and/or behavior. A single seizure may occur for no known reason. Some seizures are caused by a pathologic condition of the brain, such as a tumor. In this case, once the underlying problem is treated, the patient is often asymptomatic.

Epilepsy is defined by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke as two or more seizures experienced by a person. It is a chronic disorder in which repeated unprovoked seizure activity occurs. It may be caused by an abnormality in electrical neuronal activity; an imbalance of neurotransmitters, especially gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA); or a combination of both (McCance et al., 2010).

Types of Seizures

The International Classification of Epileptic Seizures recognizes three broad categories of seizure disorders: generalized seizures, partial seizures, and unclassified seizures.

Six types of generalized seizures may occur and involve both cerebral hemispheres. The tonic-clonic seizure lasting 2 to 5 minutes begins with a tonic phase that causes stiffening or rigidity of the muscles, particularly of the arms and legs, and immediate loss of consciousness. Clonic or rhythmic jerking of all extremities follows. The patient may bite his or her tongue and may become incontinent of urine or feces. Fatigue, acute confusion, and lethargy may last up to an hour after the seizure.

Occasionally, only tonic or clonic movement may occur. A tonic seizure is an abrupt increase in muscle tone, loss of consciousness, and autonomic changes lasting from 30 seconds to several minutes. The clonic seizure lasts several minutes and causes muscle contraction and relaxation.

The absence seizure is more common in children and tends to run in families. It consists of brief (often just seconds) periods of loss of consciousness and blank staring as though the person is daydreaming. The patient’s eyes may flutter, and automatisms (involuntary behaviors) such as lip smacking and picking at clothes may also occur. He or she is not aware of these behaviors. The patient returns to baseline immediately after the seizure. Left undiagnosed or untreated, the seizures may occur frequently throughout the day, interfering with school or other daily activity.

The myoclonic seizure causes a brief jerking or stiffening of the extremities that may occur singly or in groups. Lasting for just a few seconds, the contractions may be symmetric (both sides) or asymmetric (one side).

In an atonic (akinetic) seizure, the patient has a sudden loss of muscle tone, lasting for seconds, followed by postictal (after the seizure) confusion. In most cases, these seizures cause the patient to fall, which may result in injury. This type of seizure tends to be most resistant to drug therapy.

Partial seizures, also called focal or local seizures, begin in a part of one cerebral hemisphere. They are further subdivided into two main classes: complex partial seizures and simple partial seizures. In addition, some partial seizures can become generalized tonic-clonic, tonic, or clonic seizures. Partial seizures are most often seen in adults and generally are less responsive to medical treatment when compared with other types.

Complex partial seizures may cause loss of consciousness (syncope), or “black out,” for 1 to 3 minutes. Characteristic automatisms may occur as in absence seizures. The patient is unaware of the environment and may wander at the start of the seizure. In the period after the seizure, he or she may have amnesia (loss of memory). Because the area of the brain most often involved in this type of epilepsy is the temporal lobe, complex partial seizures are often called psychomotor seizures or temporal lobe seizures.

The patient with a simple partial seizure remains conscious throughout the episode. He or she often reports an aura (unusual sensation) before the seizure takes place. This may consist of a “déjà vu” (already seen) phenomenon, perception of an offensive smell, or sudden onset of pain. During the seizure, the patient may have one-sided movement of an extremity, experience unusual sensations, or have autonomic symptoms. Autonomic changes include a change in heart rate, skin flushing, and epigastric discomfort.

Unclassified, or idiopathic, seizures account for about half of all seizure activity. They occur for no known reason and do not fit into the generalized or partial classifications.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Primary or idiopathic epilepsy is not associated with any identifiable brain lesion or other specific cause; however, genetic factors most likely play a role in its development. Secondary seizures result from an underlying brain lesion, most commonly a tumor or trauma. They may also be caused by:

Seizures resulting from these problems are not considered epilepsy. Various risk factors can trigger a seizure, such as increased physical activity, emotional stress, excessive fatigue, alcohol or caffeine consumption, or certain foods or chemicals.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Question the patient or family about how many seizures the patient has had, how long they last, and any pattern of occurrence. Ask the patient or family to describe the seizures that the patient has had. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the type of seizure experienced, as described earlier. Ask about the presence of an aura before seizures begin (preictal phase). Question whether the patient is taking any prescribed drugs or herbs or has had head trauma or high fever. Assess any alcohol and/or illicit drug history. Ask about any other medical condition such as a previous stroke or hypertension.

Diagnosis is based on the history and physical examination. A variety of diagnostic tests are performed to rule out other causes of seizure activity and to confirm the diagnosis of epilepsy. Typical diagnostic tests include an electroencephalogram (EEG), computed tomography (CT) scan, MRI, or positron emission tomography (PET) scan. These tests are described in Chapter 43. Laboratory studies are performed to identify metabolic or other disorders that may cause or contribute to seizure activity.

Interventions

Removing or treating the underlying condition or cause of the seizure manages secondary epilepsy and seizures that are not considered epileptic. In most cases, primary epilepsy is successfully managed through drug therapy.

Nonsurgical Management

Most seizures can be completely or almost completely controlled through the administration of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), sometimes referred to as anticonvulsants, for specific types of seizures.

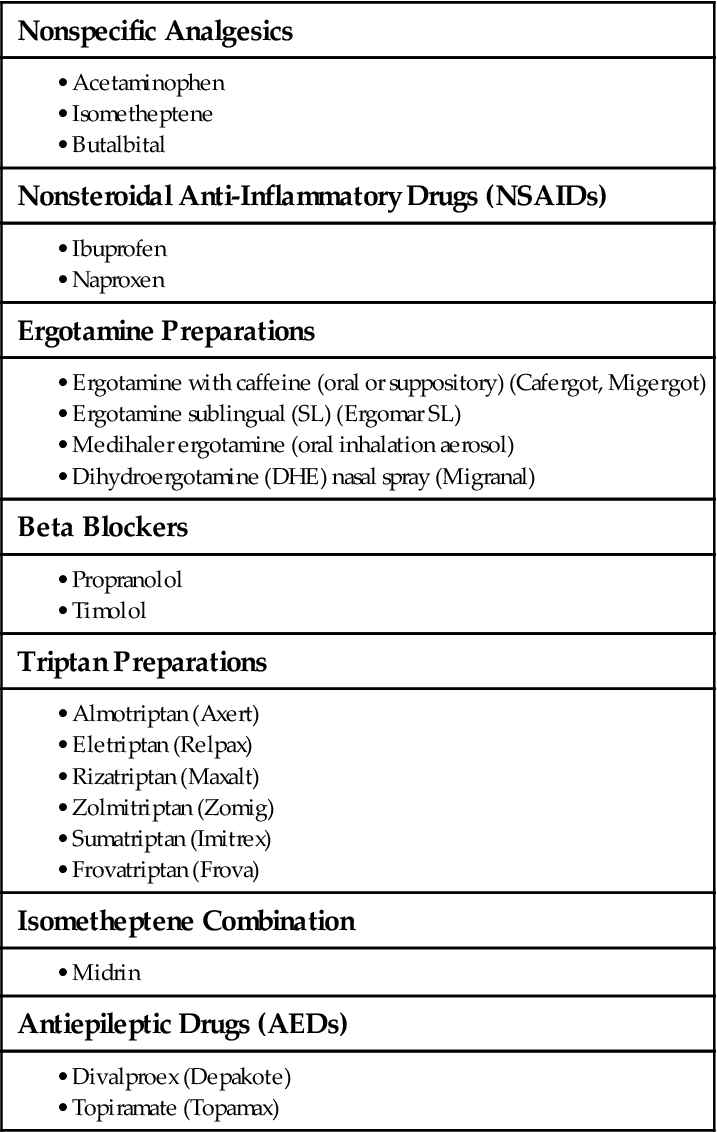

Drug Therapy.

Drug therapy is the major component of management (Chart 44-3). The health care provider introduces one antiepileptic drug (AED) at a time to achieve seizure control. If the chosen drug is not effective, the dosage may be increased or another drug introduced. At times, seizure control is achieved only through a combination of drugs. The dosages are adjusted to achieve therapeutic blood levels without causing major side effects.

Teach patients to take their drugs on time to maintain therapeutic blood levels and maximum effectiveness. Emphasize the importance of taking their antiseizure medications as prescribed. Instruct patients that they can build up sensitivity to the drugs as they age. If sensitivity occurs, tell them they will need to have blood levels of this drug checked frequently to adjust the dose. In some cases, the antiseizure effects of drugs can decline and will lead to an increase in seizures. Because of this potential for “drug decline and sensitivity,” patients need to keep their scheduled laboratory appointments.

Be aware of drug-drug and drug-food interactions. For instance, warfarin (Coumadin, Warfilone ![]() ) should not be given with phenytoin (Dilantin). Document side and adverse effects of the prescribed drugs, and report to the health care provider. Patients should be taught that some citrus fruits, such as grapefruit juice, can interfere with the metabolism of these drugs. This interference can raise the blood level of the drug and cause the patient to develop drug toxicity.

) should not be given with phenytoin (Dilantin). Document side and adverse effects of the prescribed drugs, and report to the health care provider. Patients should be taught that some citrus fruits, such as grapefruit juice, can interfere with the metabolism of these drugs. This interference can raise the blood level of the drug and cause the patient to develop drug toxicity.

Teaching for Self-Management.

Provide an educational program for the patient and family (Chart 44-4). Ask them what they understand about the disorder, and correct any misinformation. As new information is presented, be sure that the patient and family can understand it. Refer patients and families to the Epilepsy Foundation of America (www.epilepsyfoundation.org) for more information and community support groups.

Emphasize that AEDs must not be stopped even if the seizures have stopped. Discontinuing these drugs can lead to the recurrence of seizures or the life-threatening complication of status epilepticus (discussed below). Some patients may stop therapy because they do not have the money to purchase the drugs. Refer limited-income patients to the social services department for assistance or to a case manager to locate other resources.

A balanced diet, proper rest, and stress-reduction techniques usually minimize the risk for breakthrough seizures. Encourage the patient to keep a seizure diary to determine whether there are factors that tend to be associated with seizure activity. Patients should follow state law concerning allowances for driving a motor vehicle.

All states prohibit discrimination against people who have epilepsy. Patients who work in occupations in which a seizure might cause serious harm to themselves or others (e.g., construction workers, operators of dangerous equipment, pilots) may need other employment. They may need to decrease or modify strenuous or potentially dangerous physical activity to avoid harm, although this varies with each person. Various local, state, and federal agencies can help with finances, living arrangements, and vocational rehabilitation.

Seizure Precautions.

Precautions are taken to prevent the patient from injury if a seizure occurs. Specific seizure precautions vary depending on health care agency policy.

Siderails are rarely the source of significant injury, and the effectiveness of the use of padded siderails to maintain safety is debatable. Padded siderails may embarrass the patient and the family. Follow agency policy about the use of siderails because they may be classified as a restraint device. Other methods to protect the patient, such as placing a mattress on the floor, may be used instead of siderails.

Padded tongue blades do not belong at the bedside and should NEVER be inserted into the patient’s mouth because the jaw may clench down as soon as the seizure begins! Forcing a tongue blade or airway into the mouth is more likely to chip the teeth and increase the risk for aspirating tooth fragments than prevent the patient from biting the tongue. Furthermore, improper placement of a padded tongue blade can obstruct the airway.

Seizure Management.

The actions taken during a seizure should be appropriate for the type of seizure (Chart 44-5). For example, for a simple partial seizure, observe the patient and document the time that the seizure lasted. Redirect the patient’s attention away from an activity that could cause injury. Turn the patient on the side during a generalized tonic-clonic or complex partial seizure because he or she may lose consciousness. If possible, turn the patient’s head to the side to prevent aspiration and allow secretions to drain. Remove any objects that might injure the patient.

It is not unusual for the patient to become cyanotic during a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. The cyanosis is generally self-limiting, and no treatment is needed. Some health care providers prefer to give the high-risk patient (e.g., older adult, critically ill, or debilitated patient) oxygen by nasal cannula or facemask during the postictal phase. He or she is not restrained because this may cause injury and may worsen the situation, causing more seizure activity. For any type of seizure, carefully observe the seizure and document assessment findings (Chart 44-6).

Emergency Care: Acute Seizure and Status Epilepticus Management.

Seizures occurring in greater intensity, number, or length than the patient’s usual seizures are considered acute. They may also appear in clusters that are different from the patient’s typical seizure pattern. Treatment with lorazepam (Ativan, Apo-Lorazepam ![]() ) or diazepam (Valium, Meval

) or diazepam (Valium, Meval ![]() , Vivol

, Vivol ![]() , Diastat [rectal diazepam gel]) may be given to stop the clusters to prevent the development of status epilepticus. IV phenytoin (Dilantin) or fosphenytoin (Cerebyx) may be added.

, Diastat [rectal diazepam gel]) may be given to stop the clusters to prevent the development of status epilepticus. IV phenytoin (Dilantin) or fosphenytoin (Cerebyx) may be added.

Status epilepticus is a medical emergency and is a prolonged seizure lasting longer than 5 minutes or repeated seizures over the course of 30 minutes. It is a potential complication of all types of seizures. Seizures lasting longer than 10 minutes can cause death! Common causes of status epilepticus include:

Blood is drawn to determine arterial blood gas levels and to identify metabolic, toxic, and other causes of the uncontrolled seizure. Brain damage and death may occur in the patient with tonic-clonic status epilepticus. Left untreated, metabolic changes result, leading to hypoxia, hypotension, hypoglycemia, cardiac dysrhythmias, or lactic (metabolic) acidosis. Further harm to the patient occurs when muscle breaks down and myoglobin accumulates in the kidneys, which can lead to renal failure and electrolyte imbalance. This is especially likely in the older adult.

The drugs of choice for treating status epilepticus are IV push lorazepam (Ativan, Apo-Lorazepam ![]() ) or diazepam (Valium). Diazepam rectal gel (Diastat) may be used instead. Lorazepam is usually given as 4 mg over a 2-minute period. This procedure may be repeated, if necessary, until a total of 8 mg is reached.

) or diazepam (Valium). Diazepam rectal gel (Diastat) may be used instead. Lorazepam is usually given as 4 mg over a 2-minute period. This procedure may be repeated, if necessary, until a total of 8 mg is reached.

To prevent additional tonic-clonic seizures or cardiac arrest, a loading dose of IV phenytoin (Dilantin) is given and oral doses administered as a follow-up after the emergency is resolved. Initially, give phenytoin at no more than 50 mg/min using an infusion pump. An alternative to phenytoin is fosphenytoin (Cerebyx), a water-soluble phenytoin prodrug. It is compatible with most IV solutions. It also causes fewer cardiovascular complications than phenytoin and can be given in an IV dextrose solution. After administration, fosphenytoin converts to phenytoin in the body. Therefore the FDA requires the dosage to be written as a phenytoin equivalent (PE): 150 mg of fosphenytoin equals 100 mg of phenytoin. Give fosphenytoin at a rate of 100 to 150 mg/min IV piggyback.

Serum drug levels are checked every 6 to 12 hours after the loading dose and then 2 weeks after oral phenytoin has started. Teach the patient about the side and adverse effects of any AED that is prescribed (see Chart 44-3).

Surgical Management

Patients who cannot be managed effectively with drug therapy may be candidates for surgery, including vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) and conventional surgical procedures. VNS is a fairly new procedure that has been very successful for many patients with epilepsy.

Vagal Nerve Stimulation.

Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) may be performed for control of continuous simple or complex partial seizures. Patients with generalized seizures are not candidates for surgery because VNS may result in severe neurologic deficits. The stimulating device (much like a cardiac pacemaker) is surgically implanted in the left chest wall. An electrode lead is attached to the left vagus nerve, tunneled under the skin, and connected to a generator. The procedure usually takes 2 hours with the patient under general anesthesia. The stimulator is activated by the physician either in the operating room or, more commonly, 2 weeks after surgery. Programming is adjusted gradually over a period of time. The pattern of stimulation is individualized to the patient’s tolerance. The generator runs continuously, stimulating the vagus nerve according to the programmed schedule.

The patient can activate the VNS with a handheld magnet when experiencing an aura, thus aborting the seizure. Patients experience a change in voice quality, which signifies that the vagus nerve has been stimulated. They usually report a relief in intensity and duration of seizures and an improved quality of life.

Observe for complications after the procedure such as hoarseness (most common), cough, dyspnea, neck pain, or dysphagia (difficulty swallowing). Teach the patient to avoid MRIs, microwaves, shortwave radios, and ultrasound diathermy (a physical therapy heat treatment).

Conventional Surgical Procedures.

A small percentage of patients with epilepsy cannot be fully controlled with drug therapy or VNS. When all other options are exhausted, conventional surgery may be needed to improve the patient’s quality of life. The largest group of conventional surgical candidates includes those with complex partial seizures in the frontal or temporal lobe.

Before surgery, the patient is admitted to a special inpatient observation unit. While there, he or she has continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) recording, close observation, and in many hospitals, video monitoring at all times except during personal care activities. The patient is taken off all AEDs. After the seizure area is identified, electrodes may be surgically implanted into the brain tissue to identify the extent of the focal area. This step is followed by additional continuous EEG and video monitoring, as well as close observation by the nursing staff. The area is surgically removed if vital areas of brain function will not be affected.

Preoperative care is similar to that described for patients undergoing a craniotomy (see Chapter 47). Preoperative diagnostic tests include MRI and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)/positron emission tomography (PET) scans as described in Chapter 43. An intracarotid amobarbital test (Wada test) and neuropsychological testing are also done. The Wada test assesses hemispheric lateralization of language and memory after injection of amobarbital, a short-acting anesthetic. This procedure establishes the safety of surgery to preserve language memory. Neuropsychological testing evaluates memory, visuospatial function, language function, and intelligence quotient (IQ) to identify deficiencies in the brain that might correspond to areas believed to be the epileptic region. It is also used to compare preoperative and postoperative cognitive functioning.

Another surgical approach, the partial corpus callosotomy, may be used to treat tonic-clonic or atonic seizures in patients who are not candidates for other surgical procedures. The surgeon sections the anterior two thirds of the corpus callosum, preventing neuronal discharges from passing between the two hemispheres of the brain. This surgery usually reduces the number and severity of the seizures, making them more likely to respond to more conventional drug therapy. This procedure is not as commonly done as other surgeries but is very successful for some patients.

Infections

Meningitis

Pathophysiology

Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges that surround the brain and spinal cord. Bacterial and viral organisms are most often responsible for meningitis, although fungal meningitis and protozoal meningitis also occur. Viral meningitis is usually self-limiting, and the patient has a complete recovery. Bacterial meningitis is potentially life threatening. Regardless of the causative organism, symptoms are the same, but meningococcal meningitis causes the most severe presentation.

Usually, the patient has a predisposing condition such as otitis media, pneumonia, acute or chronic sinusitis, or sickle cell anemia that increases the likelihood of meningitis. A brain or spinal surgery may also contribute to the development of meningitis. Populations likely to have the disease include patients who are immunosuppressed or have infections elsewhere in the body and older adults, especially those with chronic debilitating diseases. In rare cases, tongue piercing has been associated with infections, including meningitis.

The organisms responsible for meningitis enter the central nervous system (CNS) via the bloodstream at the blood-brain barrier. Direct routes of entry occur as a result of penetrating trauma, surgical procedures, or a ruptured cerebral abscess. Otorrhea (ear discharge) or rhinorrhea (nasal discharge, or “runny nose”), which may be caused by a basilar skull fracture, may lead to meningitis as a result of the direct communication of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with the environment. The invading organisms travel throughout the CNS via the subarachnoid space. The organism produces an inflammatory response in the pia mater, the arachnoid, the CSF, and the ventricles. The exudate (pus) formed may spread to both cranial and spinal nerves, causing further neurologic deterioration. Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) may occur as a result of blockage of the flow of CSF, change in cerebral blood flow, or thrombus (blood clot) formation.

Viral meningitis, the most common type, is sometimes referred to as aseptic meningitis. It often results from a variety of viral illnesses, including measles, mumps, herpes simplex, and herpes zoster. The formation of exudate that is common in bacterial meningitis does not occur, and no organisms are obtained from the CSF. Inflammation occurs over the cerebral cortex, the white matter, and the meninges. The susceptibility of the brain tissue to the virus varies depending on which type of cell is involved. The herpes simplex virus alters cellular metabolism, which quickly results in necrosis of the cells. Other viruses cause an alteration in the production of enzymes or neurotransmitters, which results in cell dysfunction and possible neurologic defects.

Clinical manifestations of viral meningitis include fever, photophobia (light sensitivity), upper respiratory infection symptoms, headache, myalgias (muscle aches), nausea, and vomiting. Herpes simplex type 2 may cause genital lesions. A maculopapular rash is seen when the causative organism is an enterovirus. Treatment is symptomatic. If genital lesions are present, acyclovir may be prescribed.

Cryptococcus neoformans meningitis is the most common fungal infection that affects the central nervous system (CNS) of patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Fulminant invasive fungal sinusitis is also a recognized cause of fungal meningitis. The clinical manifestations vary because the compromised immune system affects the inflammatory response. For example, some patients have fever and others do not. Almost all of them have headache, nausea, and vomiting and show a decline in mental status. Treatment is symptomatic and includes IV antifungal agents.

Meningococcal meningitis is a medical emergency with a fairly high mortality rate, often within 24 hours. Unlike other types, this disorder affects the meninges, the subarachnoid space, and brain tissue and is highly contagious. It occurs most often in fall and winter when upper respiratory tract infections commonly occur. The most frequently involved organisms responsible for bacterial meningococcal meningitis are Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcal disease) and Neisseria meningitidis.

Meningococcal meningitis is the only type that occurs in outbreaks. It is most likely to occur in areas of high population density, such as college dormitories, military barracks, and crowded living areas. It also affects people with compromised immune systems and those with spleen damage or who have no spleen (Heavey, 2010).

The number of outbreaks on college campuses has been decreasing over the past few years because many states require students to be vaccinated against meningitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree